After decades of low inflation and rock-bottom interest rates, economies throughout the world are now facing a spectre unseen since the 1970s: rising inflation levels combined with the beginnings of another recession.

It is clear that we have entered a new chapter in the crisis of world capitalism, which the strategists of capital themselves are at a loss to explain.

This article asks: What conjunction of factors lie behind the present stage in capitalism’s crisis? What really causes inflation? And what effect will inflation – and the ruling class’ attempts to curb inflation – have on the class struggle?

This article was written for issue 38 of the In Defence of Marxism theoretical magazine, published earlier this year in the summer. Since it was written, events have confirmed our analysis.

As expected, central banks have begun substantially hiking interest rates to levels not seen since the 2008 crisis. And, as we predicted, despite the fact that some factors feeding into inflation – like supply chain chaos – have eased up, the ruling class’ monetarist measures have failed to bring inflation under control.

This is because, as Adam Booth explains, inflation cannot be controlled by simply loosening or tightening the money supply. Inflation is caused by a concatenation of factors, arising ultimately from this anarchic, chaotic system that is capitalism.

Like the feverish symptoms of a hospital patient, inflation is a symptom of a sick system. The only cure is socialist planning, public ownership, and workers’ control.

Across the world, the scourge of inflation is striking fear into the hearts of the working class and the ruling class alike.

For workers, rising prices across the board – from energy, to housing, to transport, to food – are leading to a cost-of-living catastrophe.

By definition, inflation means the devaluation of a currency; money buying fewer goods and services than before. Thus the purchasing power of wages has decreased.

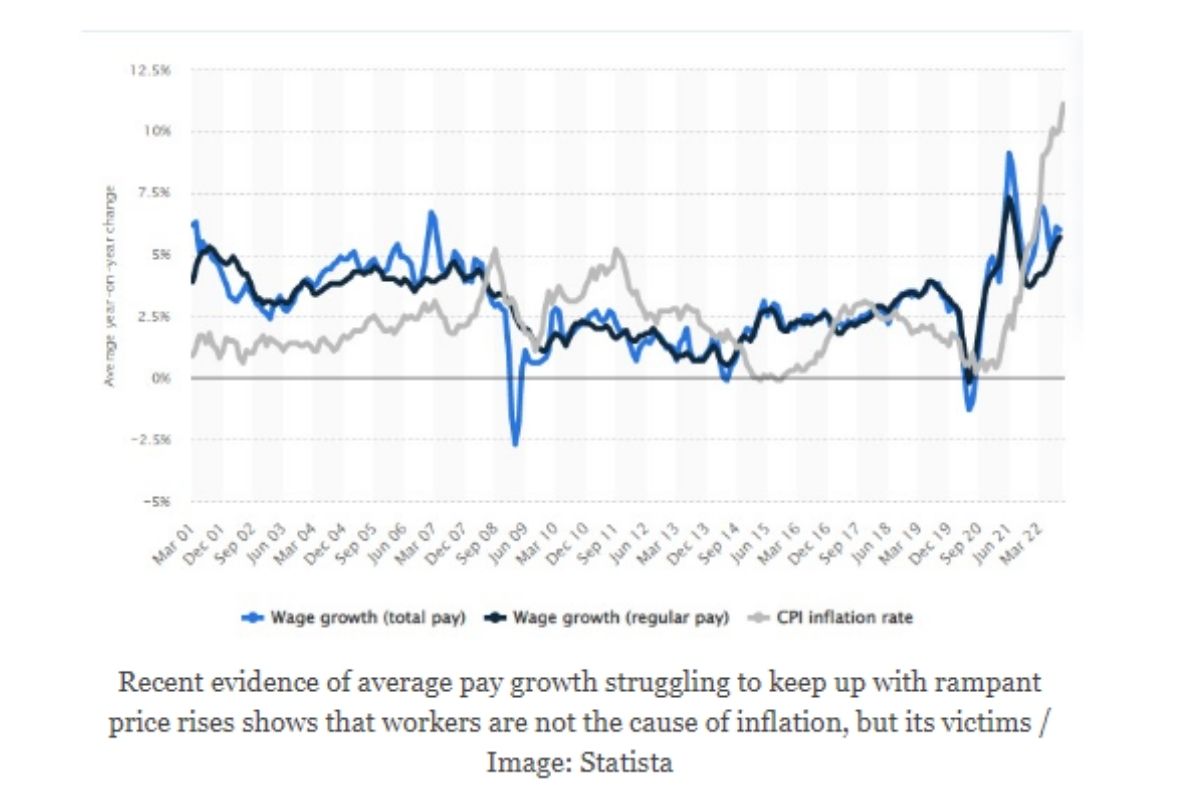

Even where workers are able to win higher pay, this is generally lagging behind increases in rents and bills, leading to a decline in real household incomes.

The headline figure for UK inflation has soared to over 11%, the highest level in four decades. Similar numbers have also been seen in the USA, with prices up by 7.7% in October compared to 12 months earlier. In Europe, the equivalent number is 10.6%. Across the advanced capitalist countries of the OECD, it is 10.7%.

For politicians and policymakers, it is not just the social and economic instability caused by inflation that keeps them awake at night, but the alarming realisation that they have few treatments for fighting this multi-pronged sickness. And even worse, that the ‘cure’ – higher interest rates and a new global recession – might be worse than the disease.

For workers suffering from the squeeze of rising costs and stagnant real wages, the vital question is: how do we fight this menace of inflation?

To answer this $64 million question (or should that be $64 billion, in today’s devalued currency?), we must first understand what inflation is and where it comes from.

Wages, prices, and profits

For all their apparent differences, in the final analysis, the Keynesians and the monetarists agree that it is the working class that must pay for this crisis. The ‘choice’ that they present for workers is between death by hanging or death by a thousand cuts.

Neither camp offers any real solution, since the problem, at root, lies with the very system that they defend: capitalism.

Stripping away their shadow-boxing, we see that these two wings of bourgeois economics are in fact united in terms of the medicine that they prescribe to tackle inflation: austerity and attacks on workers’ wages.

Bourgeois economists of all stripes, in this respect, are fond of pointing the finger at troublesome trade unionists, who are said to cause upwards price spirals with their demands for higher pay.

Similarly, it is fashionable these days for economic commentators to warn that prices will rise due to ‘inflation expectations’ – a euphemism for workers trying to keep pace with climbing living costs.

Recent evidence has dealt a blow to this reactionary nonsense, however. Average pay growth in the UK has struggled to keep up with rampant price rises over the past year, for example, despite continuing labour shortages in many vital industries and sectors. It is therefore clear that workers are not the cause of inflation, but its victims.

Indeed, far from seeing a ‘wage-price spiral’ driven by workers, there is in fact a ‘profit-price spiral’ for the capitalists – with bankers receiving record bonuses, and big business continuing to pull in eye-watering profits, despite increased costs.

Alongside this empirical rebuttal, Karl Marx theoretically answered these right-wing arguments long ago.

In his pamphlet Value, Price, and Profit, for example, based on a series of lectures delivered to the First International in June 1865, Marx polemicised against ‘citizen’ John Weston, a prominent reformist who was influenced by the liberal ideas of bourgeois economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

According to Marx, Weston’s position could be summarised as follows: “(1) that a general rise in the rate of wages would be of no use to the workers; (2) that therefore, etc., the trade unions have a harmful effect.”

Marx utilised this debate as an opportunity to outline his own economic ideas, particularly regarding the law of value, based on the labour theory of value (LTV), and the difference between values and prices.

The thrust of Marx’s exposition is that the prices of commodities – goods and services produced for exchange on the market – are not arbitrary; nor are they decided by the subjective caprices of the capitalists. Rather, prices are determined by objective laws and dynamics, which can be understood and examined.

Marx stressed that prices are not determined by the addition of wages and profits, as the bourgeois classical economists asserted. Rather, prices are, broadly speaking, the monetary expression of the value of commodities.

Prices vary according to supply and demand, Marx explained. But in a free market, under the pressure of competition, these prices should fluctuate around an average level – the value of a commodity, determined by the socially necessary labour time required to produce a given good.

It is the working class, in other words, who produce all new value in society, adding value to commodities by applying their labour in the process of production. And this value, in turn, is then distributed amongst workers and capitalists, respectively, in the form of wages and profits.

Importantly, Marx highlighted, workers themselves sell a commodity to the capitalist: their labour power; that is, their ability or capacity to work for a given hour, day, week, etc. And in return for this commodity, they receive a wage.

Labour power, in most respects, is like any other commodity. It has a value, determined by the socially necessary labour time required to produce this commodity. For labour power, this means the average time required to maintain and reproduce the working class itself, in the form of food, clothing, housing, education, and so on.

Similarly, labour power has a price: the average wage that workers receive. And like prices in general, wages can also fluctuate above or below the value of labour power through supply and demand. Unlike other commodities, however, this does not happen simply through market forces, but through class struggle.

This hits at Marx’s main point. As with prices, the profits of the capitalists are not arbitrary. They are not obtained by cheating; by ‘buying cheap and selling dear’. The laws of competition, in general, prevent the capitalists from just adding a surcharge onto their costs.

Indeed, right now, many businesses – particularly smaller ones, without the scale and pricing power of the big monopolies – are complaining that they cannot simply pass on increased costs (most notably for energy and transport) to customers, without seeing an impact on their sales.

Even if they could set prices in such a way, Marx noted, what the capitalists gained with one hand as sellers, they would simply lose with the other as purchasers, as their own costs of production (including wages) increased. It would be a case of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Rather, as Marx discusses, profits represent the unpaid labour of the working class: the surplus value that is produced above and beyond that paid back to workers for their labour power in the form of wages.

Who’s to blame?

In summary, the working class, in the course of the working day, week, or year, produces a sum of value. And, as Marx explains: “This given value, determined by the time of his labour, is the only fund from which both he and the capitalist have to draw their respective shares or dividends, the only value to be divided into wages and profits…”

Inflation, therefore, doesn’t make society richer in terms of real wealth. But it does redistribute wealth between creditors and debtors, and shift incomes around between capitalists and workers – normally to the detriment of workers, as prices rise faster than wages.

Flowing from this, Marx continues:

“Since the capitalist and workman have only to divide this limited value, that is, the value measured by the total labour of the working man, the more the one gets the less will the other get, and vice versa…

“If the wages change, profits will change in an opposite direction. If wages fall, profits will rise; and if wages rise, profits will fall.”

Every real increase in wages for workers, in other words, can only come about by biting into the profits of the capitalist class. And that is why, as we see today, the bosses – and their servants in the media, the City, and Westminster – launch such a ferocious attack against workers every time they, like Oliver Twist, dare to ask for more.

It is therefore clear that workers are not to blame for inflation, but are consistently forced into battle to maintain their living standards in the face of surging costs and the bosses’ onslaught.

“All past history proves that whenever such a depreciation of money occurs, the capitalists are on the alert to seize this opportunity for defrauding the workman,” Marx notes in Value, Price, and Profit.

Indeed, with most major markets dominated by just a handful of powerful monopolies, corporate bosses have opportunistically taken advantage of the pandemic to partake in price gouging and profiteering.

Firms in the S&P 500 stock market index, for example, saw their overall ‘earnings’ rise by approximately 50% in 2021, with profit margins remaining at all-time highs of almost 13% throughout the year. Some bourgeois analysts, meanwhile, have estimated that ‘markups’ could be responsible for more than 70% of the increase in prices in America since late 2019.

It is generally workers who are chasing after prices, then, and not the other way around. As Marx summarises in his magnum opus, Capital:

“If it were within the capacity of the capitalist producers to increase the prices of their commodities at will, they could and would do so even without any rise in wages. Nor would wages rise with a fall in commodity prices. The capitalist class would never oppose trade unions, since they would always and in all circumstances be able to do what they now do exceptionally under certain particular and so to speak local conditions – i.e. use any increase in wages to raise commodity prices to a far higher degree, and thus tuck away a greater profit…

“The entire objection is a red herring brought in by the capitalists and their economic sycophants… The effect is then taken for the cause. However, wages rise (even if seldom, and proportionately only in exceptional cases) with the increased price of the necessary means of subsidence. Their rise is the result of the rise in commodity prices, and not the cause of this.”

(Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol 2, Penguin Classics 1992 edition)

“A struggle for a rise of wages follows only in the track of previous changes,” Marx emphasises in response to Citizen Weston, “in one word, as reactions of labour against the previous action of capital.”

Fictitious capital

For Marx and Marxists, then, the answer to monetary questions must ultimately be sought in an understanding of value and its laws; of generalised commodity production and exchange; and of the profit system that flows from this.

Only armed with a Marxist understanding of value and prices, as outlined above, can we begin to make sense of the real forces and factors behind inflation – including the current crisis.

Firstly, there is the role of what Marx referred to as ‘fictitious capital’: the circulation of money in the economy without an accompanying circulation of value; money that circulates as capital – money seeking to create more money – without any associated production of commodities.

Before we go any further, however, we must first answer the question: what is money?

In essence, Marx explains, money is a universal measure of value; a standard yardstick, against which the value of all other commodities can be expressed.

Prices, in turn, are the monetary expression of value; the unit of measurement for the socially necessary labour time crystalised within commodities.

Money arises organically and historically alongside class society and private ownership, out of the needs of commodity production, exchange, and trade.

Initially, this takes the form of the money commodity: a commodity that is valuable in its own right, with its own embedded socially necessary labour time; that is capable of being exchanged for all other commodities; and that all other commodities can be compared to, thus acting as a universal equivalent.

Beginning around the 6th century BC, for example, we see the emergence of coinage, with the use of precious metals – such as gold and silver – as the money commodity. And following this, metallic-based money, in various forms, dominated for millennia afterwards, up until the 20th century.

Over time, through debasement, the precious metals circulating as money became devalued. The nominal face value of coins, in other words, became separated from the actual value of the metal circulating as money.

In the process, in place of a money commodity with its own intrinsic value, money – in the form of coins, then as paper notes, and now even just as numbers on a screen – has become a collection of mere tokens, acting as a representation of value.

A certain quantity of money, in other words, acts as a symbol for a certain quantity of values, embodied in commodities. And prices, in turn, vary according to the money supply, the amount of value in circulation, and the ‘velocity’ of money (the rate or frequency at which exchanges take place within the economy).

All else being equal, then, if the money circulating in the economy increases without a corresponding increase in circulating values, in the form of commodities bought and sold on the market, this means prices will go up accordingly.

This highlights the instability and inflationary tendencies implicit within the use of monetary tokens as a symbol of value, if these are not tied to a material base in terms of commodities with real value – as is the case today with what are known as ‘floating’ (or ‘fiat’) currencies.

At root, whether these are paper currency or digital representations, these tokens are promissory notes to pay the bearer; pledges that should be backed up by commodities with actual value – either in terms of real productive activity, or in the shape of the money commodity, i.e. gold. If not, this will lead to inflation.

Then enters fictitious capital: money thrown into circulation (as capital), without any material basis in terms of value (i.e. commodities) being produced.

This can take many forms: government bonds representing national debts; stocks, shares, securities, and other complex financial products invented and sold to investors; and state spending on unproductive projects, such as arms or roads to nowhere.

Marx contrasted this fictitious capital with that of real (productive) capital, invested in means of production and workers’ labour power; and that of money capital, the actual funds at the disposal of the capitalists.

Whereas real capital is invested to yield an actual surplus value, Marx explained, fictitious capital is an illusory claim on future profits that do not yet exist; “merely a title of ownership to a corresponding portion of the surplus value to be realised by [the actual capital invested].”

“All this paper,” Marx continues, “actually represents nothing more than accumulated claims, or legal titles, to future production whose money or capital value represents either no capital at all, as in the case of state debts, or is regulated independently of the value of real capital which it represents.”

Under the gold standard – introduced and spread in the decades following the Napoleonic Wars, in response to inflated wartime prices and national debts – the monetary tokens and paper in circulation remained anchored to a material, metallic base, namely gold.

This prevented the money supply from becoming completely divorced from the value in circulation.

The collapse of the gold standard – initially in the First World War, and then for good in the Great Depression – removed this constraint. And this was furthered by the end of the postwar Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971.

Under the Bretton Woods setup, countries’ currencies were pegged to the US dollar, which in turn was fixed to gold at a price of $35 per ounce. This was made possible by the strength of US capitalism following WW2, and the hegemonic position of US imperialism, reflected in the fact that two-thirds of the world’s bullion resided in Fort Knox. The dollar, in other words, was effectively deemed to be ‘as good as gold’.

Over the following decades, however, as US capitalism underwent a relative decline, the dollar’s strength was undermined. American balance-of-payment surpluses turned into deficits. And playing the role of the world policeman, in Korea and Vietnam, for example, US imperialism spent a fortune on arms, creating inflationary pressures that further weakened the dollar.

Eventually the tensions became unbearable, and the convertibility of dollars into gold at the previous rate became untenable. The Bretton Woods agreement was scrapped, and the era of floating currencies was born.

Ever since, sovereign governments and central banks (i.e. those with their own independent fiat currency) have been free to print money without restraint – a prerogative that the Keynesians have regularly taken full advantage of over the last century, introducing all manner of horrific inflationary distortions into the capitalist system in the process.

Limits of Keynesianism

Ironically, Keynes himself was no fan of inflation. Rather, as a self-professed champion of the “educated bourgeoisie”, he saw expansionist measures as a necessary evil in saving capitalism – in times of crisis – from the dangers of depression and deflation.

Keynes’ difference with the monetarists was not over the threat of inflation, but over how to combat it. Whilst his libertarian opponents focussed on controlling the money supply, he emphasised the need for demand-side management to subdue prices. Primarily, for the English economist, this meant restricting workers’ wages.

For example, having advocated government spending to stimulate demand during the Great Depression, during the Second World War Keynes proposed a policy of ‘deferred pay’ in order to restrict wartime demand and thus bring down prices.

Today, however, Keynesian policies (of deficit financing and government stimulus) are synonymous with inflation. Meanwhile, Keynes’ modern disciples – including the left reformists, who have wholeheartedly embraced his doctrine – are dangerously nonchalant about the inflationary risks inherent within their proposals.

In recent decades, the ruling class appeared to be blasé about the threat of inflation. When the economy was booming, they happily turned a blind eye to the contradictions fomented by cheap credit, fictitious capital, and floating currencies. And when capitalism went into crisis, they kicked the can down the road, taking desperate measures in the immediate term, at the expense of digging themselves into a deeper hole in the long run.

In this respect, the ruling class’ Keynesian response to the coronavirus crisis has undoubtedly helped to fan the flames of inflation, by again blowing a gust of fictitious capital into the world economy.

As the virus spread, society went into lockdown; high streets emptied; and production was mothballed across the planet. The global economy began to go into freefall. So the ruling class stepped in, deploying unprecedented state intervention to prevent the system from imploding.

To date, around $16 trillion has been provided globally in fiscal support, through government spending and handouts. A further $10 trillion was pumped into the economy by central banks, in the form of quantitative easing (QE) and monetary financing: using newly-printed money to fund public borrowing.

Repeated rounds of pandemic-related stimulus in the US, for example, equate to around 25% of GDP; that is to say, public spending equivalent in value to a quarter of what the country – the richest in the world – produces in a year.

Having turned on their virtual printing presses, meanwhile, central banks in the advanced capitalist countries are now loaded with government debts.

The Fed and the Bank of England hold around 40% of treasuries and 30% of gilts, respectively, whilst the equivalent figure in Japan is 44%. For comparison, prior to the 2008 crisis, the Fed held just 7% of the country’s bonds, worth around 3% of US GDP. Similarly, the European Central Bank (ECB) now holds assets worth over 60% of eurozone GDP, compared to 20% before 2008.

This provides a daunting sense of scale when it comes to the amounts of fictitious capital poured into the global economy in response to the COVID crash.

In the UK and Europe, some of this state support went towards subsidising the wages of furloughed workers. But rather than acting as an economic stimulus, this mainly replaced demand that would otherwise have collapsed had mass unemployment taken hold.

In the USA, by contrast, the government sent $250bn-worth of corona-cheques to millions of households, in an effort to boost consumption, alongside providing a temporary boost to unemployment benefits.

But with vast swathes of the economy – such as hospitality and tourism – in suspended animation, much of this money was saved, not spent. According to one US survey: 42% was spent; 27% was saved; and the remaining 31% was used to repay debts.

The result is that, as COVID restrictions have been removed, a wave of pent-up demand has been released into the economy. According to some estimates, these accumulated personal savings amounted to as much as 10% of GDP in countries like the UK (albeit distributed very unevenly across the population).

Combined with government stimulus and central bank QE, this led to a massive surge in the broader money supply, and thus in consumer demand also. Production, however, stifled by pandemic-related stoppages and shortages, has not been able to keep up. This reflects the anarchy of capitalist production and the market.

In other words, a reduced circulation of values (commodities) in the world economy is now represented by an increased circulation of money, leading to a generalised increase in prices.

This turbulence, meanwhile, has been further magnified by shifting consumer habits. This means that imbalances between supply and demand are far more pronounced in certain sectors than others, leading to dramatic price rises in these industries as resources are reallocated.

This starkly demonstrates the limits of Keynesianism, and all attempts to manage capitalism. In an effort to save their system in the short term, the ruling class has merely exacerbated all the contradictions within the global economy, leading to soaring prices, mountains of debt, and even-greater volatility and instability on the world market.

All the measures taken by the capitalists to avert crises and fuel booms in the past, in other words, are now coming back to bite them – turning into their opposite, and preparing the conditions for a far deeper crisis: economically, socially, and politically.

Arms spending

Fictitious capital, as mentioned earlier, can also appear in other forms – state expenditure on arms being a prime example.

Arms manufacturers do not produce constant capital, in the form of factories, machines, or infrastructure for productive use. But neither do they produce consumer goods, which go into maintaining and reproducing labour power – i.e. the working class.

This sector’s activity, in other words, does not productively contribute towards increasing the values in circulation. At the same time, the arms industry and its workers have to take a share of the total economic product, in the form of wages and profits.

From the perspective of the capitalist system as a whole, therefore, state expenditure on weapons is a form of unproductive consumption; a colossal drain on the economy – similar, as Keynes suggested, to paying workers to dig holes in the ground.

This, in effect, is fictitious capital rearing its head in another guise. Ted Grant explained this in Will there be a slump?: a reply to so-called ‘Marxists’ who, during the postwar boom, capitulated to Keynesianism, believing that government expenditure on arms could overcome the contradiction of overproduction.

In fact, as explained above, this arms spending only heightened the contradictions in the system, contributing towards the tensions that eventually tore the Bretton Woods setup apart. This, in turn, led to pent-up inflationary pressures exploding to the surface across the world.

Fast forward to today, and it is clear that recent promises of increased military spending by US imperialism and its allies will again serve to push up prices across the global economy.

Washington, for example, has passed a bill allowing for $40 billion in military aid to be sent to Ukraine, on top of the $13 billion in war-related donations already sent since the start of the conflict.

In March this year, meanwhile, six other NATO members pledged to increase their defence budgets by a combined $133 billion, with Germany alone accounting for over $100 billion of this amount.

In total, military expenditure by NATO countries amounts to around $1 trillion per year (70% of which is the Pentagon). This figure is up by 2% compared to 12 months previously.

Across the world, the number is over $2.1 trillion – equivalent to 2.2% of global GDP: a monstrous burden on society, diverting productive capacity and resources away from supplying basic necessities, and towards destructive wars or the scrapheap.

‘Monetary phenomenon’

The monetarists and libertarians also warn of the dangers of expansionist policies, blaming reckless and feckless governments and their central banks for provoking inflation by employing Keynesian methods and flooding the market with cheap credit.

In particular, these right-wingers frequently point to catastrophic historical examples of hyperinflation – such as Weimar-era Germany, or Venezuela and Zimbabwe in more modern times – to stress that one cannot escape a crisis by printing money.

The monetarists are correct in this assertion. As discussed above, injecting money into circulation without any corresponding increase in values (commodities produced) paves the way for runaway price increases.

Their analysis of money and inflation, however, like all of bourgeois economics, suffers from being extremely exaggerated, one-sided, and mechanical.

And their proposed remedy – deflationary austerity and attacks on wages – is a bitter pill that the working class is made to swallow, when the real problem is the decrepit capitalist system.

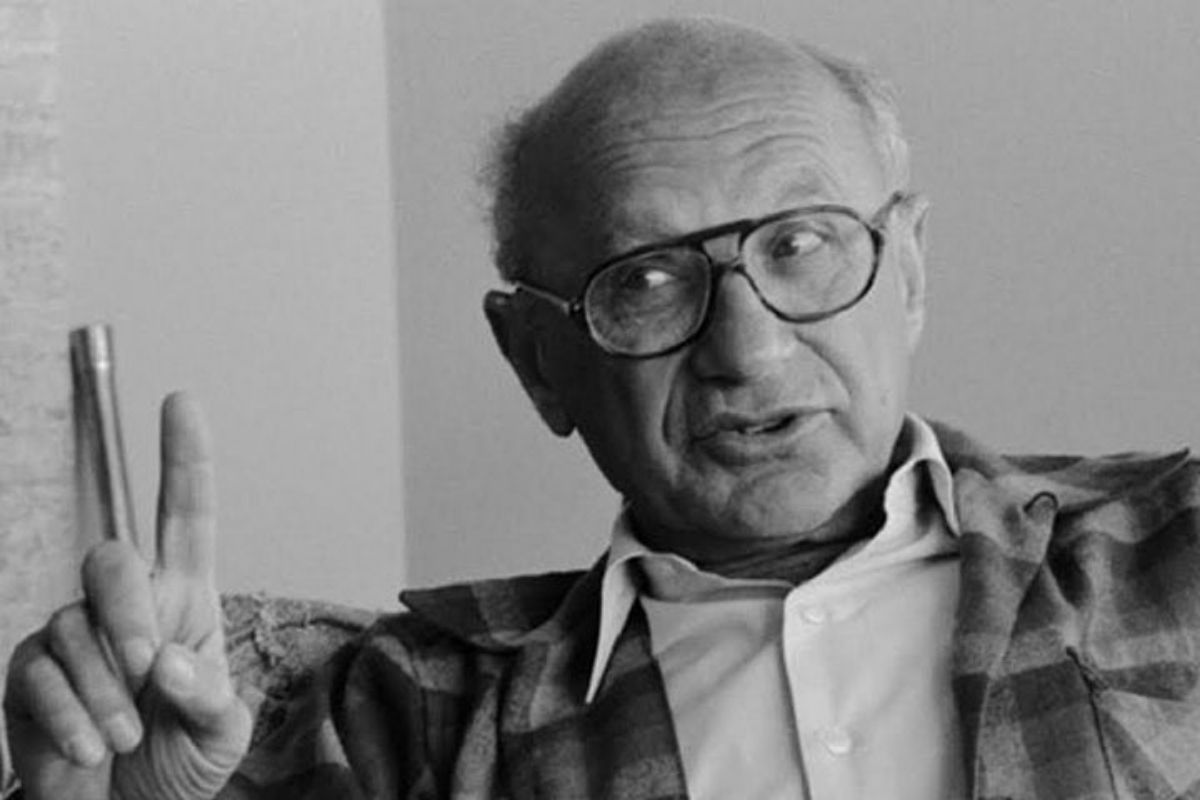

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” asserted Milton Friedman, one of the leading figures in the Chicago school of economics, famous for influencing reactionary politicians such as Republican president Ronald Reagan, Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher, and Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet.

In other words, according to Friedman and the monetarists, in all cases, it is simply increases in the money supply that are said to be behind inflation.

But this is an explanation that in fact explains nothing. It is, as Marx called it, ‘money fetishism’: idealistically imbuing money and the money supply with a mystical power, divorced from – and elevated above – the real, objective, dialectical laws that govern the dynamics of the capitalist system.

The result is to confuse cause and effect, leading to an almighty muddle, as Ted Grant explained:

“[The monetarists] take the elementary proposition that a given amount of currency would be necessary to move a given quantity of goods in a capitalist economy, at a fixed velocity of money; and that, if under these circumstances, for example, the amount of currency notes were to be doubled, prices would also double.

“They then come to the conclusion that in a situation of inflation, if the ‘money supply’ – i.e. the issue of notes and credit – is cut down, this would result in a proportionate fall in prices, or at the least stop the steady inflation of prices. They imagine that removing the symptom will cure the disease.”

At root, this is pure reductionism. Whereas Marxism seeks to analyse phenomena dialectically, in an all-rounded, many-sided manner, the bourgeois economists (of both the monetarist and the Keynesian variety) isolate just one part of an interconnected whole, and thus turn a relative truth into a gross error.

‘Too much money’ is certainly one aspect of the question. But, firstly, we must ask: if it is an excessive money supply that causes inflation, then what determines the money supply?

And secondly, saying that inflation is simply caused by ‘too much money chasing too few goods’ is not an answer. What is too much money? And why are there too few goods?

The quantity of money in the economy is presented by the monetarists as being a tap, controlled by the state, that can be turned on and off at will. Similarly, the level of production is portrayed as a fixed amount.

In reality, however, neither the money supply nor economic output is fixed or independent. Rather, under capitalism, both are subject to the same motor force: the production of profit.

The monetarists put all the onus on governments and central banks. But as Marx explains at various points throughout his three volumes of Capital, the state does not have complete control over the money supply under capitalism.

Instead, as capitalism develops, we see credit – primarily in the form of money lending by monopolistic financial institutions, such as banks – playing an increasingly important role, acting as a vital lever for the expansion of production.

What, then, primarily determines the level of credit money in circulation? In short: the production and realisation of profit. The capitalists do not borrow money simply because it is cheap, but in order to invest and make a profit.

Under capitalism, Marx notes, money appears as the “prime mover” and “permanent driving force” of the economy. And it is certainly true that the wheels of capitalism are greased with money through-and-through, with a multitude of transactions – of buying and selling – that are all reliant on money changing hands.

But this, Marx emphasises, is only an appearance. In reality, it is the dynamics of capital – the production and distribution of commodities for profit – that determine the demand for money: particularly in the form of credit, but also in regards to cash and coin.

Inflation, in other words, may indeed be a ‘monetary phenomenon’, as Friedman stated. But monetary phenomena are themselves a reflection of the laws of value – the laws governing the capitalist system: a system of generalised commodity production and exchange; a system of production for profit.

Quantitative easing

The money supply is not the only determinant of inflation, then. Money is not the motor force of the capitalist system. And monetary policy is not omnipotent. The state, in summary, cannot overcome the contradictions of capitalism.

Proof of the above came following the 2008 crash. With interest rates already reduced to near-zero, and public debts at sky-high levels, the ruling class had effectively run out of ammo when it came to fighting the crisis. Despite all their best efforts, investment and growth remained anaemic.

Central banks in the advanced capitalist countries therefore injected trillions into the world economy in the form of quantitative easing, in an attempt to increase liquidity and stimulate lending by private banks.

Within years, the US Federal Reserve had expanded its balance sheet by $4.5 trillion. In the UK, the Bank of England created around £375 billion through QE. And even the ECB got in on the act, buying up over €1 trillion worth of assets.

According to the monetarists and their ‘quantity theory of money’, such profligacy should surely have led to widespread inflation. After all, as discussed above, it seems elementary that – all else being equal – if one (say) doubles the amount of money in circulation, then this will simply double the price of everything.

But not all else is equal. And this much-predicted inflation never materialised. Indeed, in Europe and elsewhere, the bigger fear throughout this period was that of depressive deflation.

This was due to a number of factors. On the one hand, for decades prior to the pandemic, various forces acted to put a downward pressure on prices.

Most importantly, far from the world economy overheating in this period, global overproduction – reflected in an abundance of supply relative to demand – instead weighed down on prices.

Added to this, globalisation helped to keep costs down, providing cheaper sources of labour and raw materials, alongside greater efficiency from economies of scale. Similarly, technological advances (particularly in terms of computing) helped to reduce the costs of capital.

On the other hand, much of this vast infusion of QE money never actually found its way into consumers’ pockets – i.e. into the ‘real’ economy; into actual circulation.

Rather than directly pumping money into the system, in the form of a ‘helicopter drop’ of cash into ordinary people’s hands, central banks created new money to buy up financial assets (such as treasuries, bonds, etc.) from private banking institutions. And this, in turn, it was hoped, would encourage these banks to provide cheap credit to business and households.

Instead, the bankers cut their lending and boosted their profits; businesses sat on hoards of idle cash; and investors funnelled this easy money into a frenzy of speculation, fuelling bubbles in stocks, housing, and cryptocurrencies.

And while central banks were opening up the taps at one end, governments were sucking demand out of the economy at the other, in the form of austerity and cuts to public spending. Loose monetary policy, in other words, was accompanied by tight fiscal policy.

At the same time, with markets saturated and excess capacity across the board, business investment remained stagnant, meaning that there was little demand for credit from the banks.

This, in turn, meant that whilst the state was creating new money with total abandon, the overall money supply – that is, the amount of money actually in circulation – barely altered compared to its historic trend.

The main sources of effective demand, therefore, were all either subdued or in decline. Household consumption was limited by meagre real-wage growth, if any. Government spending was being cut. And private investment was flat. Capitalism was stuck in a funk.

All of this highlights the limits of what can be achieved through monetary policy. The capitalists produce in order to make profits. If they cannot do this, then production and investment will grind to a halt. And, as this recent example shows, no amount of cheap money will convince them otherwise.

Money fetishism

On the other side of the debate amongst bourgeois economists, the neo-Keynesian preachers of ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ (MMT) fall into the same trap as the monetarists they criticise, sharing their mechanical, stupefied fixation on the power of money – their money fetishism.

The MMTers, however, turn the argument of their opponents inside out. Like the monetarists, they also wrongly see money as the ‘driving force’ behind capitalism. But rather than calling for tight monetary policy on the back of this, they draw the opposite conclusion: naïvely and falsely believing that governments can stimulate production by printing money.

The fact is that capitalism cannot be managed – neither through monetary policy, nor through tax-and-spend reforms. In fact, the ‘solutions’ advocated by MMT zealots, as emphasised already, are a surefire recipe for inflation, as seen today and throughout history, with workers left paying the price.

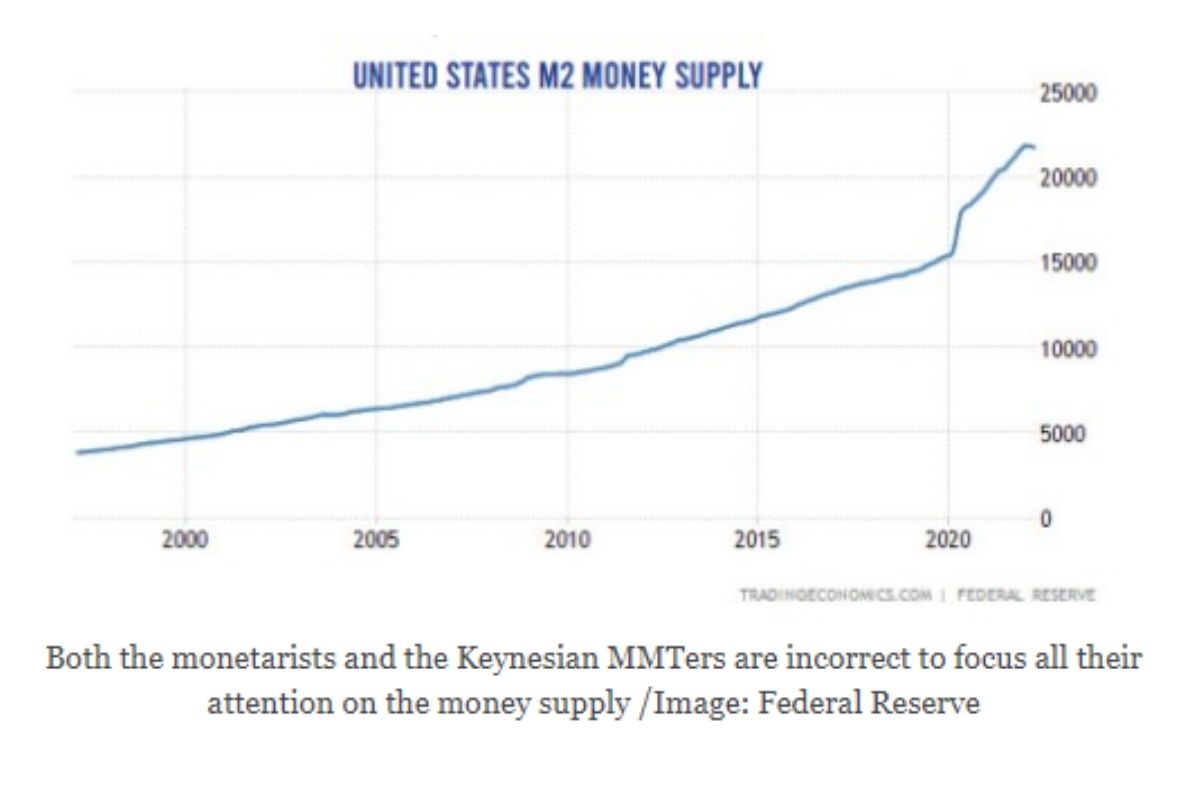

Both the monetarists and the Keynesian MMTers, then, are incorrect to focus all their attention on the money supply, and to fetishise the power of money under capitalism.

Instead, like Marx, we should be focussing on uncovering the real, objective laws that govern the movements of prices and the dynamics of capitalism. Only then can we have a truly scientific understanding of the capitalist system: a necessary precursor to pointing the way out of this crisis.

In the same way, as with money under capitalism, it is not blood alone that gives vitality to the human body. A healthy blood supply is certainly essential for transporting oxygen and other important nutrients to various organs and tissues. But it is not responsible for producing these; nor does the circulatory system set its own volume and velocity.

The monetarists, in this respect, are like mediaeval leechers, hoping to cure sickly patients by sucking excess blood out of them. The Keynesians, meanwhile, propose little more than a blood transfusion and a sticking plaster to heal a deeply infected wound.

Neither, however, address the underlying disease: capitalism itself.

Senile system

For the monetarists, as mentioned above, the solution to inflation lies in tight monetary policy. Some even call for a return to the gold standard: rigidly tying the money supply to a tangible commodity, such as gold.

Looking at the history of inflation under capitalism, there is a certain logic to this suggestion. After all, as already noted, prices have soared dramatically since the gold standard was abandoned in the interwar period, giving central banks carte blanche to print money in fiat currencies.

According to analysis by economists at the Bank of England, for example, prices in the UK increased by a factor of 20 between 1948-1994, compared to a mere trebling of prices in the almost-three-century period from the foundation of the Bank in 1694 to the end of WW2. And most of this earlier inflation in fact occurred in three periods of war, when the gold standard was largely defunct: the Napoleonic Wars; the First World War; and the Second World War.

The monetarists again confuse cause and effect, however. The gold standard (and later the Bretton Woods arrangement) collapsed not because of any political mistake, but due to the unbearable contradictions that had accumulated in the global capitalist system.

The imperialist powers first abandoned the gold standard with the onset of the Great War, as they attempted to fund their war efforts by printing money; and then again (after a brief restoration) in the 1930s, during the deepest crisis in the history of capitalism, as they pursued expansionist monetary policies in order to stimulate the economy, fund government deficits, and provide liquidity to failing banks.

In essence, this crisis of the monetary system was a reflection of the crisis of the capitalist system; a rebellion of the productive forces against the barriers of private ownership and the nation state.

Inflation seen since is a symptom not of reckless governments, but of the fact that we are in the epoch of imperialism; the epoch of capitalism’s senile decay. As Leon Trotsky explained in his speeches to the Communist International following the First World War, it is a sign of the deteriorating health of the system, which can only be kept alive by a steady drip of money-printing and debt.

Until recently, the bourgeois hubristically believed that they had successfully abolished inflation. The monetarists, for example, boasted that – under their ‘independent’ direction – prices had been brought under control in recent decades, resulting in an era of relatively low inflation and unemployment in the advanced capitalist countries.

As already explained, however, this period of subdued inflation was not thanks to monetarist methods, but was the product of objective factors – such as overproduction, globalisation, automation, and others – that combined to keep a lid on prices.

It is true that the ruling class has pushed deflationary policies of austerity and wage cuts since the 1970s, at least. But the result of this was economic and social devastation, which was only (partially) alleviated by a massive expansion of credit.

And the counterpoint to this has been the vast debts accumulated by governments, corporations, and households across the world over this period – again piling up the contradictions, which eventually burst open with the onset of the 2008 crash.

Bouts of inflation and mounting debts, in this respect, are two sides of the same coin. Both are a reflection of the impasse of capitalism, which requires ever-larger injections of fictitious capital in order to survive. But all of this only adds to the contradictions, paving the way for even bigger, more explosive crises down the line.

Supply shocks

It is clear, then, that fictitious capital – in the form of government stimulus and central bank QE – is at least partially responsible for the epidemic of inflation that has ensued on the back of the epidemic of COVID-19.

But a deluge of demand is only one side of the equation. The other is the supply-side problems that are wrecking the world economy, with bottlenecks and labour shortages throttling the production of many key goods.

Supply chains are stretched beyond their limits. Transport links and shipping routes are predicted to be backed up for months, or even years. And businesses in numerous sectors are still struggling to fill job vacancies.

Scarcity in one area, meanwhile, can send powerful ripples across the wider economy. A surge in demand for microchips, for example, has led to stoppages in industries further down the line, such as car manufacturing.

Added to this chaos, a series of additional shocks have knocked out large supplies of key commodities for the world economy.

Most notable has been the impact of the Ukraine war and western sanctions against the Putin regime on the supply of oil and gas. Ukraine and Russia are also both major exporters of wheat, whilst the latter is an important producer of raw materials such as aluminium, palladium, and fertilisers.

Similarly, there are concerns surrounding China’s ‘Zero COVID’ policy, which has prompted strict lockdowns in industrial regions of the country that are nodal points for global production and trade.

Again, understanding the relationship between value, prices, and money, it becomes evident how this process has also stoked inflation.

Prices are rising in response to sharp imbalances between supply and demand. This is particularly acute for vital components of production and distribution, such as energy and transport. And this then has a profound knock-on effect for prices in general, causing inflation to become widespread.

In most advanced capitalist countries, for example, it is rising energy prices that are responsible for a significant proportion (over half) of official inflation figures. In the eurozone, energy and food account for nearly three-quarters of inflation.

But whilst prices are rising, values in many cases are not. The socially necessary labour time required to drill oil in the USA, for example, has not really been impacted by bans on Russian crude.

As a result, the big fossil fuel monopolies are registering bumper super-profits, taking advantage of the crisis in order to widen their margins, instead of investing to provide affordable, clean energy for all.

Market anarchy

With their ardent faith in the power of the market, the leading representatives of the ruling class believed that such disruptions would quickly pass, and that harmony and equilibrium would soon be restored.

Demand would dampen following an initial post-lockdown surge. Supply would catch up as the pandemic subsided and the economy returned to ‘normal’. Inflation, they hoped, would be no more than an ephemeral fever.

But the sectors listed above are mostly dominated by monopolies and cartels, such as OPEC (the oil producing countries), who more often-than-not prefer to respond to higher prices by increasing their profits, rather than increasing production.

The sums required to enter these markets, meanwhile, make it near-impossible for new suppliers to join, preventing competition and keeping prices artificially inflated.

At the same time, with globalisation has come a tremendous level of monopolisation and specialisation. Certain critical industries – such as the production of silicon computer chips – are now concentrated in just one or two countries. And if these are cut off from the rest of the world, then fragile supply chains and global markets can easily begin to fracture.

At root, all of this is a product of the anarchy of capitalism: a system of private ownership and production for profit.

For decades, compelled by competition, the bosses have pursued ‘just-in-time’ production methods. This has meant cutting away at any fat, eliminating redundancy, and over-extending supply chains – all for the sake of squeezing out ever-greater profits.

Similarly, in the advanced capitalist countries, there has been a lack of long-term investment in industry and infrastructure, in favour of short-term financial speculation.

But this myopic approach has introduced enormous fragility into the system, leaving economies vulnerable to ‘accidents’ such as wars, pandemics, and natural disasters.

Take gas, for example. In recent years, gas storage capacity in the UK has been whittled down from over 10% of annual demand to less than 2%. Even small fluctuations in domestic demand or available imports, therefore, can result in a worrying shortfall and massive hikes in energy prices – as has been seen over the last year.

Or look at oil. The start of the pandemic saw a huge collapse in the demand for oil, resulting in negative prices in the US for the first time in history. Two years later, as lockdowns end and demand returns, dormant drills and pumps cannot be brought back online fast enough.

Along with the effects of the conflict in Ukraine, this has served to consistently push the price of Brent crude above $100 per barrel in recent months, with US President Joe Biden now imploring oil producers to ‘drill, baby, drill!’

The same fundamental process can be seen across the world economy. The invisible hand cannot keep up with volatile swings in supply and demand; nor with the repeated hammer blows that are raining down on the capitalist system, knocking out the supply of a number of essential goods and raw materials.

“A shock of such depth and breadth is without precedent,” states the Economist in a recent feature about the impact of the war on the international supply of key commodities. “Rebalancing the market thus seems impossible without a forced reduction in demand.” In other words: a return to rationing.

The market, in short, has failed. Far from efficiently allocating resources, it has proved unable to provide the basic necessities of life. In place of this capitalist chaos, we need a socialist plan of production.

Globalisation unravels

Alongside fictitious capital and supply shocks, the other major component in today’s inflation crisis is a real increase in the costs of production.

Whereas the first two factors reflect the upward pressure of market forces on prices, due to imbalances in supply and demand, this third ingredient in inflation signifies a relative growth of values – that is, of the socially necessary labour time required to produce and distribute certain commodities.

Today, this is primarily linked to the question of globalisation and protectionism.

In recent decades, as already discussed, globalisation – alongside automation and attacks on the working class – has acted to place a powerful downward pressure on prices.

As China, Russia, and Eastern Europe opened up to the world market, new sources of cheap labour and resources became accessible to western capital.

Furthermore, as mentioned above, the establishment of global supply chains, with the development of communication and transport, led to a concentration of production, in the shape of giant multinational monopolies in many sectors. And with this came economies of scale: improvements in productivity that helped to bring down costs.

Now, however, this process is beginning to slow down, and even go into reverse.

Rising tensions between the capitalist powers are sharpening the contradictions in the world economy. Globalisation is retreating; economic nationalism is on the rise; and global supply chains are beginning to unwind – all of which is accelerating in response to the pandemic, the Ukraine war, and the ensuing sanctions on Russia.

The result is an unravelling of international trade, which, for decades following the Second World War, had been steadily expanding compared to global economic output.

This will have the effect of ‘balkanising’ capitalism, fracturing the world market, reducing efficiencies in production, and increasing prices (relative to wages, the price of labour power).

Joe Biden, for example, is now trumpeting the slogan ‘Made in America’, as he looks to reshore manufacturing to the USA. In reality, this means erecting new barriers to trade – imposing additional costs on producers.

This reveals the severe impact of the ruling class’ political decisions on inflation: Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ policies; Boris Johnson’s Brexit belligerence; or US imperialism’s drawn-out proxy war with Russia in Ukraine, to name but a few – decisions which are themselves taken in response to the crisis and contradictions of capitalism, but which in turn threaten to pour petrol on an already-raging fire.

And above all, it highlights once again how the nation state, alongside private ownership, acts as the fundamental barrier to the development of the productive forces.

‘Stagflation’

The overall result is that the world economy is now heading towards the nightmare scenario of rising inflation alongside slowing growth – a killer combo referred to by bourgeois economic commentators as ‘stagflation’.

Faced with such a prospect, the ruling class are stripped of the weapons in their arsenal upon which they would usually rely.

Interest rates, for example, are a blunt tool, aimed at subduing demand by tightening the money supply. But consumer demand is already being dampened by higher prices, with household incomes and accumulated savings unable to cover escalating bills – hence the projections of slower growth, with previous hopes for a robust post-pandemic rebound now extinguished.

Furthermore, increasing interest rates also intensifies the burden of debt, pushing up borrowing costs. And in the current context of highly-indebted households, business, and governments, this could provoke a sharp slump.

The present situation has therefore drawn comparisons with the 1970s: the last time that the advanced capitalist countries faced ‘stagflation’, with similar (or worse) levels of inflation, simultaneous to an economic recession and high unemployment.

Inflationary pressures then included both fictitious capital and supply shocks, such as the oil crisis of 1973, which saw energy prices soar as a result of the Yom Kippur war and the subsequent oil embargo.

By the end of the decade, the situation was getting out of control, with the annualised inflation rate in the USA reaching over 13% by December 1979.

That same year, Democratic US President Jimmy Carter appointed self-proclaimed “practical monetarist” Paul Volcker as chair of the Fed. Upon assuming the role, Volcker acted immediately to hike up the central bank’s base rates from around 10% to 20%.

The Fed’s aim was to artificially provoke a recession by restricting credit, in the hope of pushing unemployment up and wages down – an aim in which Volcker and the ruling class succeeded.

This move came with tremendous collateral damage, however, with the fallout felt across society. To this day, the impact can be seen in terms of the scars of deindustrialisation in the Rust Belt.

As with every analogy, however, there are important limits to this historical parallel. 2022 is not 1980. Both inflationary crises share certain similarities – most notably, coming on the back of a decade or more of economic, social, and political instability. But there are also important differences.

Firstly, the ruling class are entering today’s crisis with far greater levels of debt and fictitious capital sloshing around their system.

Global debt reached an all-time high of 360% of GDP in 2020, jumping by 28 percentage points as a result of pandemic-related state spending. In the USA, federal debts now stand at almost 140% of GDP. By comparison, the White House went into the 1980s with historically low debts of only 32% of GDP.

The same is generally true for all countries. The world has never been so awash with debt. A spike in interest rates at this time will therefore cause far more economic devastation and financial contagion than in Volcker’s day, provoking mass bankruptcies of countries, companies, and families.

Similarly, the global economy is far more integrated now than then. This means that the impact of the Fed’s decisions will now reverberate across the planet. The de facto default of Sri Lanka recently, and panicky flutters on the stock market, are a harbinger of what lies ahead.

Finally, unlike in the 1980s, the capitalist system today is not on the verge of a boom. Back then, the era of globalisation was just beginning, with the expansion of international trade receiving a significant boost as first China, and then Eastern Europe and Russia, began to open up their economies to the world market. This provided new sources of profitable investment for the capitalists, helping to alleviate the decline back in the West.

By contrast, as already discussed, globalisation now is starting to break down. And far from facing a period of upswing, we are entering a period of stagnation and crisis, with markets saturated and economic nationalism on the rise.

Whilst the Volcker-induced recession was short and sharp, therefore, a hard landing today is likely to be far more bumpy and protracted – coming on top of the 2008 slump and the corona crash, with all the unresolved contradictions that these crises brought with them.

On the other side, if governments continue their deficit financing, and central bankers don’t take steps to tighten the supply of credit and money, then this will only add to debts and fuel inflation even further, leading to further falls in real wages and living standards for workers and the poor.

Whatever decision the ruling class takes, therefore, will lead to disaster: either in the short term, or by preparing the conditions for even more intense crises down the line. On the basis of capitalism, in other words, all roads lead to ruin.

And whether through austerity or inflation, or both, it is the working class who will be asked to foot the bill. The stage is therefore set for intense class struggles everywhere.

Culprit is capitalism

It can be seen, then, that inflation is a complex phenomenon, involving the interaction of a number of factors, processes, and dynamics. It is a many-headed hydra. But whichever way you examine it, the blame does not lie with workers. The real culprit is capitalism and its contradictions.

It is the ruling class and its representatives who have recklessly sprayed money around the global economy since 2008 (and over the last century), like an arsonist being invited to tackle a blazing inferno.

It is the capitalists who have profiteered from scarcity; speculating and hoarding, instead of investing in real production.

It is the multinational monopolies who have extended supply chains to breaking point, and cut all redundancy and resiliency to the bone, in an effort to eke out ever greater profits.

It is the bosses and billionaires who have driven down workers’ pay and conditions in a race to the bottom, leading to declining real wages alongside labour shortages in vital industries.

It is capitalist politicians, in defence of their own nations’ capitalist class, who have gone down the path of protectionism: implementing tariffs; reshoring production; and undertaking competitive devaluations of their currencies – all in order to export the crisis elsewhere, with the costs borne by workers at home and abroad.

And it is the imperialist warmongers who have wasted society’s wealth on arms and weapons, and imposed savage sanctions, causing enormous economic dislocation and driving up the price of oil, gas, and other important commodities – all for the sake of expanding their markets and spheres of influence.

Above all, it is the capitalism system that is to blame: an inherently anarchic system, in which our lives and futures are left in the invisible hands of the market; where society’s abundant resources are squandered for the sake of the bosses’ profits, instead of being utilised rationally to meet the needs of people and the planet.

In the final analysis, inflation is a symptom of the anarchy and decay of the capitalist system; a plague that will only ever truly be cured if we rid ourselves of the market economy, by taking production out of private hands, and placing it under common ownership and workers’ control.

“The working class,” wrote Marx in Value, Price and Profit, “ought not to forget that they are fighting with effects, but not with the causes of those effects; that they are retarding the downward movement, but not changing its direction; that they are applying palliatives, not curing the malady.”

The only genuine, lasting solution for the working class, therefore, is to expropriate the billionaires and plan the economy along socialist lines.

That is the revolutionary task in front of us. Capitalism is chaos and crisis. This senile system cannot be patched up. It must be overthrown.