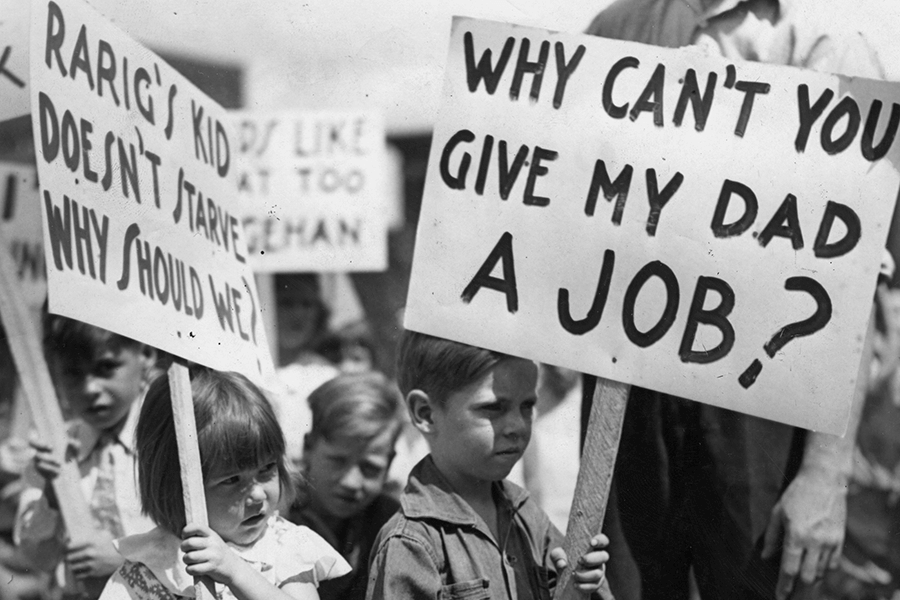

The coronavirus pandemic has triggered what is likely to be the deepest crisis in the history of capitalism. Comparisons to the Great Depression of the 1930s are being made across the board, as the world economy collapses and unemployment shoots up in all countries.

In the UK, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is predicted to fall by at least 15% in the next quarter. In the US, Morgan Stanley predicts an annualised fall of 30%. Almost 10 million have lost their jobs in America already. In Britain, one million applied for Universal Credit in the space of just two weeks.

Desperate times call for desperate measures. The ruling class is throwing everything they have at the situation. The problem is, their arsenals are already empty from their attempts to fight the last recession.

With interest rates at 0%, monetary policy has reached its limits. Years of quantitative easing have led to a case of diminishing returns. And public debts are already sky-high from bailing out the banks during the last global crisis. In short, they have run out of ammo to tackle this crisis.

As a result, governments across the world have been left with no choice but to pump money into the economy in an effort to prop up the system. Already, trillions have been promised by the advanced capitalist countries alone, including $2.2 trillion in central bank measures and $4.3 trillion in state spending.

And in all likelihood, this is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what will be required to avert a complete market meltdown in the weeks and months ahead.

All socialists now?

Many observers cannot believe their eyes. Overnight, a laissez-faire Tory government has turned towards unprecedented state intervention in the economy, promising £330 billion (15% of GDP) to help small businesses and homeowners, and a limitless amount to subsidise workers’ wages.

Many observers cannot believe their eyes. Overnight, a laissez-faire Tory government has turned towards unprecedented state intervention in the economy, promising £330 billion (15% of GDP) to help small businesses and homeowners, and a limitless amount to subsidise workers’ wages.

In the USA, it seems that Donald Trump has been convinced into implementing a ‘helicopter drop’ of money over American households, with every citizen potentially set to receive a cheque for over $1,000 in the post.

At a similar time of crisis in the early 1970s, Republican US President Richard Nixon was said to remark that “we are all Keynesians now”, as his administration turned towards expansionist economic policies. Similarly, today, many are remarking that “we are all socialists now”, as big business governments everywhere throw free-market orthodoxy out of the window in an effort to save the system.

“Boris must embrace socialism immediately in order to save the liberal free market,” declared one writer in the Tory mouthpiece, the Telegraph. The coronavirus crisis is “turning Tories into socialists” announced another headline, this time in the Conservative journal, the Spectator.

Those on the left who have spent years arguing against austerity and for demands such as a ‘universal basic income’ (UBI) understandably believe that their time has come. Even outgoing Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn declared that the Tory government’s emergency measures were a vindication of his economic programme. Here, after all, is the famous ‘magic money tree’ that the Conservatives had claimed did not exist!

In particular, advocates of Keynesian policies – of government stimulus, state spending, and top-down economic management – feel that their ideas have finally been proven correct.

Ditto with their contemporary acolytes: those who subscribe to ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ (MMT) – promoted by leading lights of the Democratic Party in the USA, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), and by influential economic advisors in the British labour movement

Recent events seem to offer activists the perfect rebuttal to right-wing critics who ask how radical policies will be paid for. Want free healthcare and education? No problem, we’ll just print money. Mass investment in green energy? Don’t worry, we can turn on the government’s taps. Give everyone a UBI? Easy – just add it to the bill!

The problem is, eventually this bill must be paid. The real question is: by whom?

What is Keynesianism?

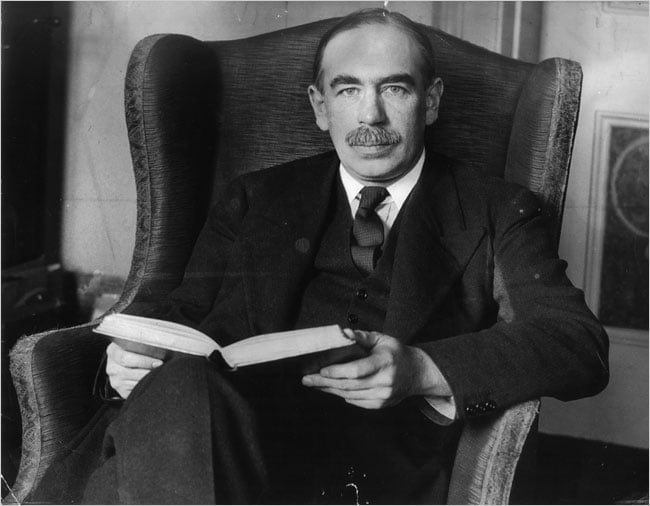

Truth be told, Modern Monetary Theory is a bit of a misnomer. In reality, it is not much of a theory. Nor is it particularly modern. Indeed, at root it is really just a rehash of the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, who believed that governments could manage and regulate the capitalist system by ‘stimulating demand’.

Truth be told, Modern Monetary Theory is a bit of a misnomer. In reality, it is not much of a theory. Nor is it particularly modern. Indeed, at root it is really just a rehash of the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, who believed that governments could manage and regulate the capitalist system by ‘stimulating demand’.

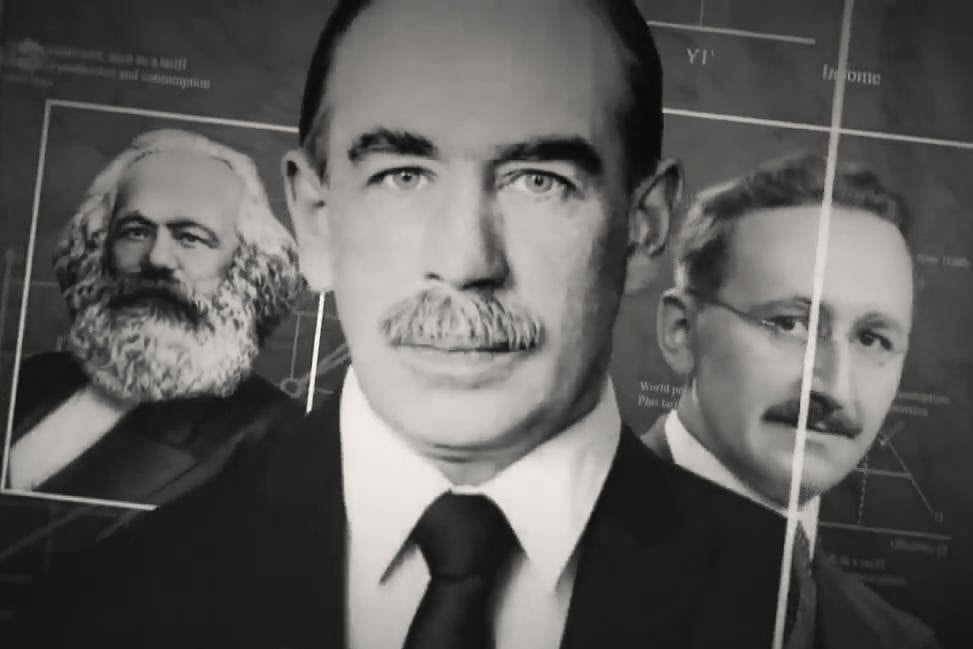

Keynes was an English economist, who came to prominence for his writings on the turbulent inter-war period. Despite being embraced today by the labour movement and the left, Keynes was a devout Liberal. He was actively opposed to socialism, Bolshevism, and the Russian Revolution, proudly declaring that, “the class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie”.

Indeed, his ideas were not intended to help the working class, but were an attempt to provide capitalist governments with a strategy on how to get out of crises. In particular, his most famous work – his General Theory – was a direct response to the Great Depression, and the mass unemployment seen in America, Britain, and across Europe at the time.

Whilst no fan of socialism, Keynes was critical of the so-called ‘free market’. He correctly identified – as Marx had done many decades before – that the ‘invisible hand’ of the market was not omnipotent; that supply and demand would not always match in perfect ‘equilibrium’.

Instead, capitalism periodically found itself – like in the 1930s – stuck in a vicious circle, with rising unemployment leading to falling demand; falling demand leading to a collapse in business investment; and collapsing investment leading to rising unemployment; and so on.

The solution, Keynes asserted, was for the state to step in any make up for the shortfall in demand. In other words, governments should spend where private business would not, in order to ensure that workers had money in their pockets to spend.

His concern was less that workers might eat, and more that they might buy and consume, thus providing a market – the ‘effective demand’ – that the capitalists required in order to sell their produce and make a profit.

In short, Keynes’ programme was not one aimed at ameliorating the lives of the working class, but at saving capitalism from its own contradictions.

In this respect, we see echoes today of Keynes’ ideas in the policies being carried out in response to the coronavirus-induced crisis. The establishment are not so much worried about people dying in the short term, as they are about the potential depression that will follow if workers do not have jobs, money, and the ability to purchase the commodities churned out by the capitalists in the future.

As in the Great Depression, then, the concern of the ruling class and their economic advisors is not about saving ordinary people’s lives, but about the viability of their system – the profit system.

The New Deal

Notably, Keynes’ ideas were clearly influential in shaping the New Deal: President Roosevelt’s programme of public works that were intended to stimulate US economic growth during the Great Depression.

Notably, Keynes’ ideas were clearly influential in shaping the New Deal: President Roosevelt’s programme of public works that were intended to stimulate US economic growth during the Great Depression.

After all, in his General Theory, the English economist even suggested that the government could boost demand by burying money in the ground and getting workers to dig it back up.

“There need be no more unemployment,” stated Keynes. “It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like,” he continued, “but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.”

Today, these same ideas are raised in relation to proposals for a Green New Deal (GND), which has become a signature demand of the left, advocated by AOC in the US and by left-wing Labour activists in the UK.

The only problem that the advocates of a new New Deal fail to mention, however, is that the original did not work. The slump continued long after its implementation (in fact, it became worse with the rise of ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ protectionism). Unemployment even went up. Only with the onset of the Second World War and the mopping up of workers into the army and the arms sector did unemployment fall.

Even Keynes himself was forced to admit defeat. “It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case — except in war conditions.”

The same can be seen in China in recent years, where the largest ever Keynesian programme of construction has been undertaken in the last decade, in an effort to escape the impact of the global capitalist crisis. But the result has been a massive increase in public debts, on one side, and the ludicrous contradiction of ghost cities alongside a huge housing crisis, on the other.

This is the logical conclusion of Keynesian attempts to bureaucratically manage a capitalist, profit-driven economy. There is no reason to believe a new New Deal would fare any better today in America, Britain, or anywhere else.

At the same time, it is also important to recognise the differences between these (failed) Keynesian experiments of the past and the measures being enacted by policy makers and world leaders today in similarly desperate circumstances.

Traditional Keynesian steps were an attempt to stimulate demand – and, in turn, business investment – through government spending. At the present time, however, the aim is not so much to boost demand; after all, production is largely paralysed by the pandemic.

Instead, the primary goal is just to maintain the system on life support until the current situation subsides; to ensure that the bosses still have a workforce to exploit when the pause button is lifted. And, above all, to provide workers with a basic means of living, in order to prevent a social explosion from occurring in the meantime.

No free lunch

Like their traditional Keynesian predecessors, MMT supporters believe that there should never be any slump, or any need for austerity and balanced budgets, since governments can always step in by creating money and spending it.

Like their traditional Keynesian predecessors, MMT supporters believe that there should never be any slump, or any need for austerity and balanced budgets, since governments can always step in by creating money and spending it.

Provided countries have their own ‘independent’ currency, we are told, the government can never run out of money, since the state can always choose to pay for any debts by ‘printing’ more.

Yes, money can be created ‘out of thin air’. But value and demand cannot. The state can create money. But the state cannot guarantee that this money has any value. Without a productive economy behind it, money is meaningless. Money is only a representation of value. And real value is created in production, as a result of the application of socially necessary labour time.

The money that a state creates, therefore, will only be of any worth in so far as it reflects the value that is in circulation in the economy, in the form of the production and exchange of commodities. Where this is not the case, then this is a recipe for inflation and instability.

For example, all other things being equal, if the government prints two notes where there was one previously, this devalues the currency by half, and therefore prices in the economy will double. Medieval monarchs – and their subjects – learnt this the hard way, when prices soared and inflation shot up in response to endless debasements of the currency.

At the end of the day, there is no such thing as a free lunch when it comes to capitalism. Governments do not have any money of their own. State spending ultimately must be paid out of taxation or out of borrowing. And neither creates demand, but merely shifts it around the economy.

Firstly, take taxes. These must either fall on the capitalist class, which bites into investment. Or they must fall on the working class, which bites into consumption. In either case, the effect is to restrict demand, not create it.

Similarly with government borrowing. Money borrowed today from the capitalists must be paid back tomorrow – and with interest. In other words, demand can be ‘stimulated’ today through government borrowing, but only by cutting into demand in the future.

The state can try to avoid taxes and borrowing by printing money. But it cannot print teachers and schools, doctors and hospitals, or engineers and factories. If government spending pushes demand above that which can be supplied, then market forces will push up prices across the board – that is, it will generate inflation.

This is the ultimate limit to any government’s ability to create and spend money – the productive capacity of the economy: the economic resources available to a country in terms of its industry, infrastructure, education, population, and so on.

At the same time, whilst the state can create money, it cannot ensure that this money is put to use. It is not the state that creates the demand for money, but the needs of capitalist production. And this production is ultimately driven by profit. Businesses invest, produce, and sell in order to make a profit. Where the capitalists cannot make a profit, they will not produce. It is as simple as that.

Capitalism and class

Of course, if society’s needs are not being provided and produced by the private sector, then the government can step in and provide them directly through the public sector. But the logical conclusion of this is not to create more money, or to provide everyone with a ‘universal basic income’, but to take production out of the market by nationalising the key levers of the economy as part of a rational, democratic, socialist plan.

Of course, if society’s needs are not being provided and produced by the private sector, then the government can step in and provide them directly through the public sector. But the logical conclusion of this is not to create more money, or to provide everyone with a ‘universal basic income’, but to take production out of the market by nationalising the key levers of the economy as part of a rational, democratic, socialist plan.

But you cannot plan what you do not control. And you cannot control what you do not own. Keynesianism, however, avoids this key question of economic ownership.

Indeed, Keynesian economic analysis is completely devoid of the issue of class; seemingly ignorant of the fact that we live in a class society, composed of antagonist economic interests: those of the exploiters, and those of the exploited.

Ultimately, as long as the economy remains dominated by big business and private monopolies, any money pumped into the system will go to pay for commodities – food and shelter, etc. – that are produced by the capitalists.

In other words, all this money will end up in the hands of profiteering parasites. This is the real problem with reformist demands like UBI, which do nothing to challenge the power of the capitalist class.

At the end of the day, neither the Keynesians nor their MMT/UBI descendents propose fundamentally altering the current economic relations and the broken dynamics that flow from these. Private property, for them, remains inviolable and sacrosanct. The anarchy of the market is untouched.

Their strategy, in summary, is one that saves and patches up capitalism, rather than overthrowing it.

We must tackle the roots of the capitalist system: private ownership and production for profit. Only by bringing in common ownership over the means of production and implementing a socialist economic plan can we satisfy society’s needs. We cannot print our way to socialism.

Marxism vs Keynesianism

Today, even in times of ‘boom’, the febrile global economy operates far below its productive capacity. This ‘excess capacity’ has become a hallmark symptom of a system that has long outlived its usefulness. Even at its height, capitalism can only successfully utilise about 80-90% of its productive abilities. This falls to 70% or less in times of slump. In past recessions, the figure falls to as low as 40-50%.

Today, even in times of ‘boom’, the febrile global economy operates far below its productive capacity. This ‘excess capacity’ has become a hallmark symptom of a system that has long outlived its usefulness. Even at its height, capitalism can only successfully utilise about 80-90% of its productive abilities. This falls to 70% or less in times of slump. In past recessions, the figure falls to as low as 40-50%.

But the question never asked by the Keynesians (of all flavours) is how we have ended up in this situation in the first place?

“The use of MMT [and Keynesianism in general] is akin to pumping up a flat tyre,” remarks Larry Elliott, economics editor of the Guardian. “Once it is fully inflated there is no need to carry on pumping.” But what is the cause of the original puncture?

Why isn’t our full productive capacity being utilised? Why has the economy become stuck in this downward spiral of low investment, unemployment, and stagnant demand? Why must the government step in and save the system?

To this, the Keynesians have no answer. They merely state that ‘excess capacity’ is the result of a lack of effective demand. Businesses are not investing because there is not enough demand for the goods they produce. But why?

Marxism, by contrast, provides a clear, scientific analysis of the capitalist system, its relations and laws, and why these intrinsically lead to crises. These, in the final analysis, are crises of overproduction. The economy collapses not simply because of a fall in demand (or confidence), but because the productive forces come into conflict with the narrow limits of the market.

Production under capitalism is for profit. But to realise a profit, the capitalists must be able to sell the commodities they produce.

Profit, at the same time, however, is appropriated by the capitalists from the unpaid labour of the working class. Workers produce more value than they receive back in the form of wages. The difference is surplus value, which the capitalist class divides amongst itself in the form of profits, rents, and interest.

The result is that, under capitalism, there is an inherent overproduction in the system. It is not simply a ‘lack of demand’. Workers can never afford to buy back all the commodities that capitalism produces. The ability to produce outstrips the ability of the market to absorb.

Of course, the system can overcome these limits for a time though reinvestment of the surplus into new means of production; or through the use of credit to artificially expand the market. But these are only temporary measures, “paving the way,” in the words of Marx, “for more extensive and more destructive crises” in the future.

The 2008 crash marked the culmination of such a process – a climax that was delayed for decades on the basis of Keynesian policies and a boom in credit alike. But now a new, even deeper crisis has hit – and neither the Keynesians, the MMTers, nor anyone other than the Marxists can offer a way out.

At most, Keynesianism and MMT provide a palliative medicine for a chronic disease. But neither can diagnose this disease correctly, nor offer a genuine cure.

Socialism or barbarism

The capitalists today are throwing everything – including the kitchen sink – at the problem, in a desperate attempt to keep their system from collapsing. But what they give to workers in the form of wages subsidies and government spending today, will be taken away through austerity tomorrow.

The capitalists today are throwing everything – including the kitchen sink – at the problem, in a desperate attempt to keep their system from collapsing. But what they give to workers in the form of wages subsidies and government spending today, will be taken away through austerity tomorrow.

Those in the labour movement calling for Keynesian-style measures are no doubt full of good intentions. But, as the old saying goes, the road to hell is paved with such well-meaning wishes.

Demands for Keynesian policies, MMT, UBI and the rest are not just wrong but harmful – harmful because they sow illusions, preparing the way for disaster and disappointment.

In this respect, we must shout loudly like the little boy in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale – the emperor has no clothes! We have a duty to offer a word of warning to workers and youth: do not believe those trying to foist their quack remedies upon you. Now is not the time for the wiley charms of charlatans and snake-oil salesmen.

We do not criticise Keynesianism and MMT from the same position as the apologists of the ‘free market’, however. No, our criticisms come from a Marxist perspective – from the standpoint of what is good for the world working class; from what is necessary to abolish capitalism and liberate humanity.

Capitalism is at an impasse. It can offer society nothing but barbarism. Only a clear socialist alternative of common ownership, workers’ control, and democratic economic planning can provide a way forward for humanity.