The current upswing in industrial militancy is unprecedented in the last 30 years. We have to go back to the 1970s to find something comparable.

That decade saw a rebirth of the class struggle, after an era of relative calm since the end of the Second World War. We can therefore learn a lot about today’s strikes and class struggles from this period.

Setting the stage

As early as 1966, there were signs of what was to come, when the National Union of Seamen (NUS) struck against poor wages and conditions. This was the first strike of the NUS since 1911, having not even joined the General Strike of 1926.

This was followed in 1967 by a dramatic change of leadership in the engineering workers’ union. The right-wing incumbent was defeated by a self-described Marxist called Hugh Scanlon.

Shortly afterwards, another radical left-winger, Jack Jones, was elected as the leader of the General Workers’ Union. Political shifts in the leadership of important unions are often a harbinger of big struggles to come.

In the late 1960s, the Labour government published a white paper called ‘In Place Of Strife’. As the title suggests, Prime Minister Harold Wilson and co. were looking to curtail the class struggle. This document outlined a massive attack on trade union rights.

It provoked uproar in the ranks of the trade union movement. Scanlon and Jones demanded that the Trade Union Congress (TUC) convene immediately to discuss how to respond.

The movement against the white paper came from the rank and file of the unions. It was in this context that the Communist Party, which had around 30,000 members on paper at the time, formed the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions. This was an unofficial network of shop stewards.

In late 1969, it called an unofficial political strike against the attacks on the trade unions. This was the first political strike in Britain since 1926. It set the stage for the turbulence of the next decade.

Opening shots

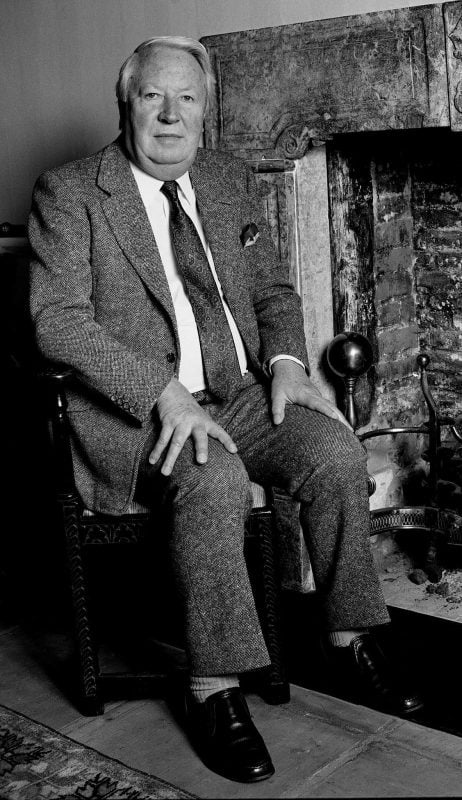

A Tory government under Edward Heath was elected in 1970. It found British capitalism in a feeble state.

A Tory government under Edward Heath was elected in 1970. It found British capitalism in a feeble state.

The previous several decades had seen a relative decline in the strength of British capitalism. The increase in living standards since 1945 had not kept pace with other European countries. Industrial production had been growing by 1.5% per year, but in the USA and Germany it was growing by 3%.

Between 1945 and 1970 manufacturing exports had fallen from 25% of the world total to around 10%. The rate of profit was falling for British capitalists, who failed to invest. They became increasingly parasitic and short-sighted.

Heath and the Tories wanted to reverse this trend of decline for the British capitalist class. Their solution was to attack workers, drive down wages and conditions, and restore the rate of profit. They also wanted to close those businesses which they saw as uncompetitive.

Despite a bullish approach, they ran into difficulties straight away. Within one month of being elected, they declared a state of emergency in the face of the first official dockworkers’ strike since 1926. The dockers were soon joined by local authority workers.

The following year, the government was rocked by a dispute involving the Upper Clydeside shipbuilders who were trying to save their jobs. This was after the government had identified them as an uncompetitive industry. The Tories hoped to shut them down by scrapping their subsidies.

The shipbuilders organised a work-in, which involved occupying their workplaces and carrying on the work. It was a defiant statement that the workers were willing and able to work and be productive, in the face of the government’s efforts to throw them on the scrap heap.

This caught the imagination of workers all over the country. There were solidarity demonstrations everywhere, and occupations in other factories. The movement was so strong that it forced a government U-turn on the policy of cutting subsidies to certain industries.

Kill the Bill

This rattled the Tory government. Clearly, the unions would need to be tamed sooner rather than later if the Tories wanted to carry through their policies.

The establishment introduced the centrepiece of their strategy to attack the working class: the Industrial Relations Bill. This proposed even harsher attacks on the trade unions. It involved huge state regulation of the unions. The class struggle was escalating.

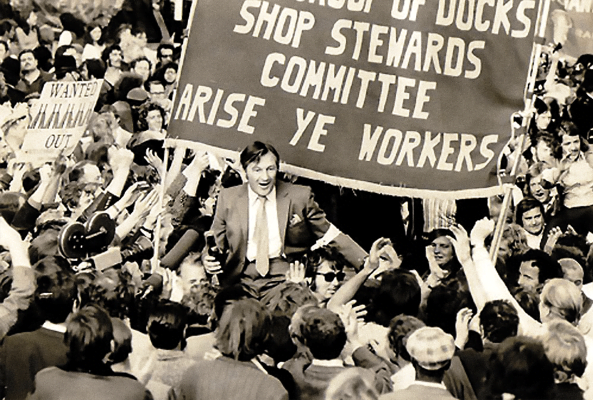

Scanlon, Jones, and other left-wing trade union leaders led the opposition to the Industrial Relations Bill. But once again, most of the opposition came from below. Demonstrations and strikes involving half-a-million workers were called around the country. 300,000 people marched in London under the banner of ‘Kill the Bill’.

This was being pushed forward by the semi-official shop stewards’ network of the Liaison Committee. Many of the trade unions’ so-called leaders were being dragged along by the rank and file.

The whip of Tory reaction drove the movement forward. Such is the ebb-and-flow of the class struggle. There is no gradual, uninterrupted crescendo of class struggle, from local strikes to international insurrection. Instead, there are leaps forwards and backwards, as events unfold.

In March 1971, there was an unofficial strike in which two million workers participated. The Liaison Committee used this to successfully pressurise the leaders of the TUC to advocate defiance of the rules imposed by the Industrial Relations Act.

The Battle of Saltley Gate

Another example of the impact that a union’s rank and file can have on its leadership came in 1972.

Another example of the impact that a union’s rank and file can have on its leadership came in 1972.

At that time, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) was dominated by the right wing. But the leaders were coming under pressure to act, as inflation eroded the miners’ living standards. More radical activists were being elected to the local and regional leaderships of the NUM.

The pressure to take action led, in early 1972, to official strike action in demand of a 47% pay increase.

The TUC, under pressure from below, called for the members of other unions to refuse to move coal around the country. This was met with massive support.

The government did have certain stockpiles of coal in anticipation of a crisis. They tried to use these stockpiles to break the strike and minimise its impact.

Attention fell on a place called Saltley in Birmingham, which had a large stockpile and was one of the few that remained open.

In Birmingham, 40,000 engineering workers voted to go on strike in support of the miners. Immediately after the vote, 10,000 of them marched on the Saltley gas works, where the coal was stored.

There they joined 2,000 miners who were already picketing the gas works, facing off against 1,000 police officers, trying to stop the coal being moved.

Arthur Scargill, at that time a local NUM organiser, describes what happened at Saltley on that day.

“Some of the lads…were a bit dispirited…And then over the hill came a banner and I’ve never seen in my life as many people following a banner. As far as the eye could see it was just a mass of people marching towards Saltley…Our lads were jumping in the air with emotion – fantastic situation…I started to chant…‘Close the Gates! Close the Gates! And it was taken up, just like a football crowd.”

The gates were closed. It was a spectacular victory for the miners.

The government panicked, called an inquiry, and recommended a 20% wage rise for the miners. It was a total humiliation for the Tories.

The Pentonville Five

Things went from bad to worse for Heath’s administration. During the summer of 1972 there was an almighty industrial battle on the docks in London. Two haulage firms went to court to try to stop the dockers’ union picketing their workplaces during the dispute, and requested that the court fine the unions under the provisions of the Industrial Relations Act.

Things went from bad to worse for Heath’s administration. During the summer of 1972 there was an almighty industrial battle on the docks in London. Two haulage firms went to court to try to stop the dockers’ union picketing their workplaces during the dispute, and requested that the court fine the unions under the provisions of the Industrial Relations Act.

One of these haulage firms succeeded, and the court granted an injunction against the union. On the evidence of private detectives, the bosses secured the arrest of five trade unionists for breaching the injunctions, and had them sent to Pentonville prison.

As soon as the arrests were discovered, 44,000 dockers immediately downed tools and walked out. 130,000 workers in other industries did the same. The movement spread like wildfire.

The pressure on the TUC leaders was instantaneous and immense. The leaders convened a meeting and decided to call a one-day general strike at the end of July, which would have been the first in Britain since 1926.

This posed a huge risk for the ruling class and the government. Under the circumstances, a one-day general strike could easily snowball into something more prolonged – potentially even developing into a revolutionary situation, beyond the control of the TUC bureaucracy.

The overzealous actions of an insignificant haulage firm had, under the heightened conditions of class struggle, brought Britain to the brink of an epic industrial showdown, which the ruling class was not confident of winning.

Such was the volatility of the situation. Sharp turns and sudden changes were implicit. Echoes of those conditions are growing louder today.

The government accordingly panicked once again. The Tories conjured up someone called the Official Solicitor, who has never been heard of before or since. He reinterpreted the law, discovered a loophole, and ordered the immediate release of the Pentonville Five.

This was another massive victory for the labour movement.

The Shrewsbury 24

The mood among the working class was jubilant and confident. For the first time since 1926 there was an official building workers’ strike in 1972. Flying pickets of strikers would go from picket line to picket line, shoring up support and plugging any gaps.

The government hated these flying pickets because they were particularly effective, as the Battle of Saltley Gate had proved.

The Tories decided to make an example of some of these flying pickets, which they did in north Wales in February 1973. The government arrested and framed 24 workers on charges of intimidation, violence, and conspiracy.

They were taken to court and given an overtly political trial. Fourteen were convicted and received up to three years in prison.

Scandalously, these workers were forced to finish their sentences under the Labour government elected in 1974. It was not until March 2021 – 47 years after their arrest – that the Court of Appeal finally overturned these political convictions.

Despite this setback in the struggle, the general line of march was towards more radical and militant action. The working class was outraged, but not cowed, about what the Tories had done to the Shrewsbury 24. They were determined to intensify the struggle.

Workers bring down the Tories

1972 was a year of industrial insurrection. After such convulsions, there was a slight lull in 1973. But at the end of 1973, a new miners’ strike began to develop. Inflation was putting pressure on the miners once again.

The Tory government tried to isolate the miners and turn the public against them. The Tories declared a three-day-week, blackouts of television and street lights, and other measures, citing the disruption to fuel supplies caused by the NUM.

This was an attempt to intimidate the NUM, but it failed. The miners voted for strike action in larger numbers than ever before.

The Heath government responded with an even bigger gamble. They called a general election asking the question: Who do you want running the country – us or the unions?

The answer was ‘not you’. And the Tories were booted out of office in February 1974.

Capitalism’s B-team

In 1974, there was a world slump. It was the end of the post-war boom. Unemployment shot to over one million in Britain. Internationally there was the Carnation revolution in Portugal, the collapse of the Junta in Greece, and the turbulent twilight of the Franco dictatorship in Spain.

All of this, coupled with industrial struggle and economic collapse, was spawning plots and conspiracies within the ruling class.

A high-ranking military officer in Britain wrote a book called ‘low-intensity operations’, in which he said the main threat for the army is not external but internal. Specifically, he referred to the working class in Britain and their organisations, such as the trade unions.

There were military manoeuvres at Heathrow airport, in which a takeover of the airport was carried out by the military, ostensibly as a training exercise, but without informing the government. In fact, this was a threat by the military to the civilian government.

This is the context in which a Labour government came to power. Cowed from the start, the new Wilson government immediately started doing the ruling class’ work for it, as a loyal B-team, while the Tory A-team was out of action.

The Labour government immediately introduced a policy of wage restraint, despite massive inflation, which reached 25% in 1975. This meant that 1974-77 saw the greatest fall in real wages of any comparative period prior to that. That was presided over by a Labour government, carrying out the diktats of big business in the face of a capitalist downturn.

After a period of Tory rule, the Labour Party leaders were supported by the working class to a certain degree, at least at first. The workers wanted them to succeed, and wanted to give them time to do their work.

It soon became clear, however, that the Labour leaders were simply doing the bidding of the ruling class. Despite this, the trade union leaders refused to stand up to the government on behalf of their members.

Even Jones and Scanlon supported the wage restraint policy. They didn’t like it, but they couldn’t see any way forward except supporting a Labour government.

These leaders never looked beyond the confines of capitalism and reformism. They lacked the revolutionary socialist perspective of Will Thorne and the New Unionists of the 1890s. So they backed austerity and convinced workers to follow their lead.

In doing this, these left trade unionists held the working class back. And they were uncritically supported in doing so by the Communist Party and the Liaison Committee.

In 1976, there was a sterling crisis, and the IMF had to step in to bail out Britain.

As is well known, when the IMF bails out a country, it comes with strings attached. The conditions for the bailout were £3bn of cuts to public services.

The conditions were designed to be especially harsh, because the IMF didn’t trust the Labour government – with its links to the organised working class and its strong left wing – to carry out the necessary policies.

Nevertheless, the Labour government bent the knee and accepted the bailout and the conditions imposed by the IMF. It was behaving as the humble servant of the capitalist class.

Unions move into opposition

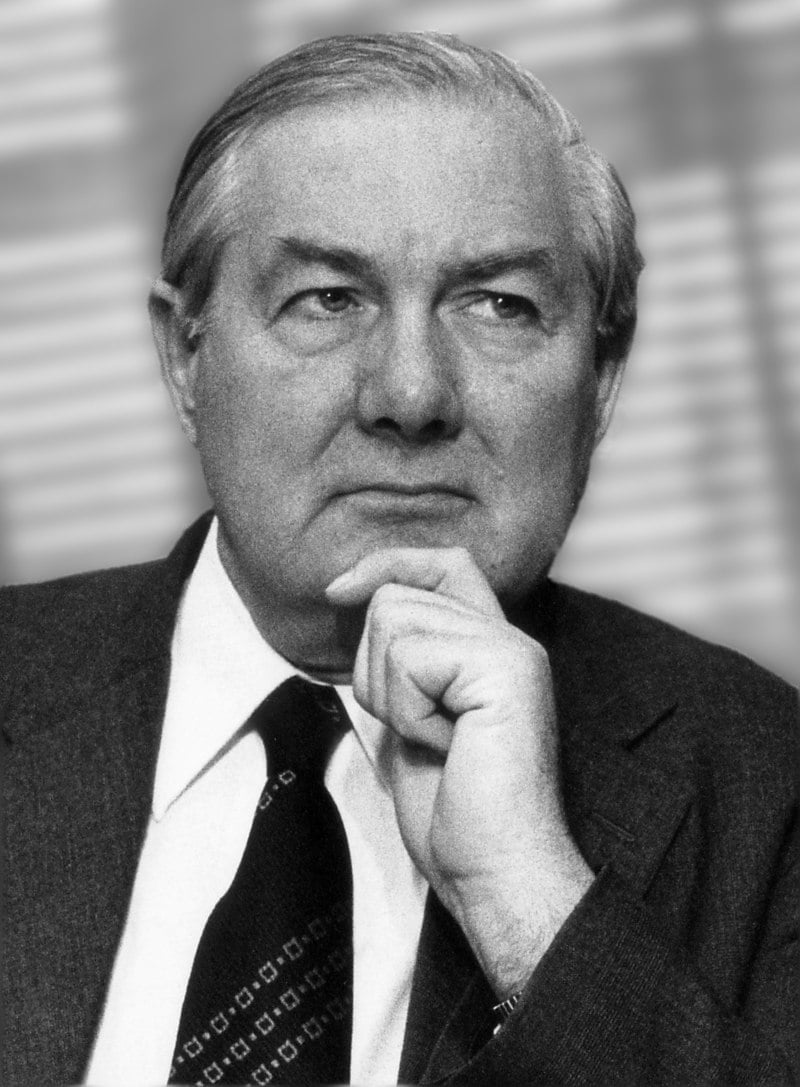

Wilson resigned, and Callaghan took over as Labour leader and Prime Minister in 1976. He pursued policies of harsh austerity as required by the ruling class.

Wilson resigned, and Callaghan took over as Labour leader and Prime Minister in 1976. He pursued policies of harsh austerity as required by the ruling class.

Finally, after two years of holding back the working class, the union leaders caved to the pressure of the rank and file, and moved into action against the government.

A wave of disputes began against the Labour administration. These were mostly on the question of wages, as workers struggled to keep their heads above the water in the context of rampant inflation.

The mood was reflected by the Fire Brigades Union, whose members voted for strike action, even in the face of opposition to action from the union’s right-wing leadership. Such was the fury at the government’s wage restraint and austerity policies.

Eventually the pressure from the ranks was so great that the TUC itself, which had been supporting the Labour government’s wage restraint policies since 1974, was forced to come out against the government.

The Winter of Discontent of 1978-79 saw a huge wave of industrial action against the Callaghan government. Between October 1978 and March 1979, ten million working days were lost to industrial action.

Lorry drivers, local authority workers, health workers, and many more were on strike. The struggle affected every part of society. It led, in the end, to the fall of the Labour government in 1979. Callaghan called an election and lost to Thatcher, opening up a new chapter in the history of the class struggle in Britain.

Throughout this decade, the working class demonstrated its power. It brought down governments. In factory occupations, it showed it could organise production. It was butting up against the limits of capitalism, and posing the question of socialism.

Ultimately, however, this was not enough, as the resulting election of Thatcher shows.

What is needed is to combine this industrial militancy with revolutionary political leadership, without which capitalism cannot be overthrown.