We are proud to republish an edited article on the 1926 general strike by Ted Grant, originally written in April 1973. At that time, Britain was rocked by a wave of strikes, and a general strike was inherent in the situation.

Today, after years of relative acquiescence, we are once again seeing a growing number of strikes. The idea of a general strike has once again been raised. It is quite possible that this belligerent Tory government and the trade union leaders could stumble into one.

A general strike, however, poses the question of power. It is therefore essential that we learn the lessons of the defeat of 1926, and prepare ourselves for the explosive events that lie ahead.

You can read the full original version of this article at the Ted Grant Internet Archive.

The causes of the 1926 general strike lay in a similar situation to the position which is developing at the present time.

In 1925, the ruling class had a policy of deflation, instead of – as at present – inflation. But the results for the working class are the same. It is the choice of death by fire or death by a thousand cuts.

In 1926, the position of the ruling class was that of a direct assault on the wages of the working class. The Tory Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin declared on 30 July 1925 that: “All the workers in this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet.”

The miners were asked to accept a reduction of 13% in wages, to starvation levels, and to work an extra hour. This attack on the miners – and on all sections of the working class – was because of the decline of British capitalism.

With an antiquated industry, the only way Britain could succeed in maintaining a hold on world markets, in the face of more modern and up to date rivals, was at the expense of the working class.

The British capitalist class wished, as now, to put the burden of its own inefficiency and incapacity onto the shoulders of the working class.

The working class, in solidarity with the miners and in defence of its own living standards, was prepared to resist. The transport unions and other sections issued instructions to black the handling and transporting of coal if the miners were locked. The shadow of conflict loomed.

Despite the complaints of the right-wing Tories, Baldwin and the government engaged in a temporary retreat in order to thoroughly prepare for a showdown with the miners and with the whole of the working class. A £23 million subsidy was given for nine months to allow the government time to complete its preparations.

At the same time, the Samuel Commission was appointed to go into the question of the mining dispute. After nine months, they recommended increased hours, lower wages, and district agreements – policies that had already been rejected!

The Tory government prepared an “Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies” (OMS); a civil guard, which the British fascists joined; Special Constables; and an elaborate network for each county in Britain to confront the TUC and the working class

The working class in Britain had been swinging to the left, following the coming to power of the Baldwin government in 1924. The expression of this move to the left was the organisation of the Minority Movement in the trade unions, with a left-wing programme, which succeeded in organising in its ranks 1,250,000 members – a quarter of the organised trade union movement.

The leaders of the left wing in the TUC made far more radical speeches and gestures than the left at the present time. An ‘Anglo-Russian Committee’ of Russian and British trade union leaders – to cement an alliance allegedly to fight war – was organised, on which the left-wing leaders of the TUC General Council were prominent.

The left leaders were immensely popular throughout the working class, and gave very fiery speeches, some even coming out for the ‘socialist revolution’. They reflected the pressure of the masses, thoroughly aroused and alarmed at the threatened attacks. A.J. Cook, the miners’ leader, went around saying that he was “proud to be a follower of Lenin”.

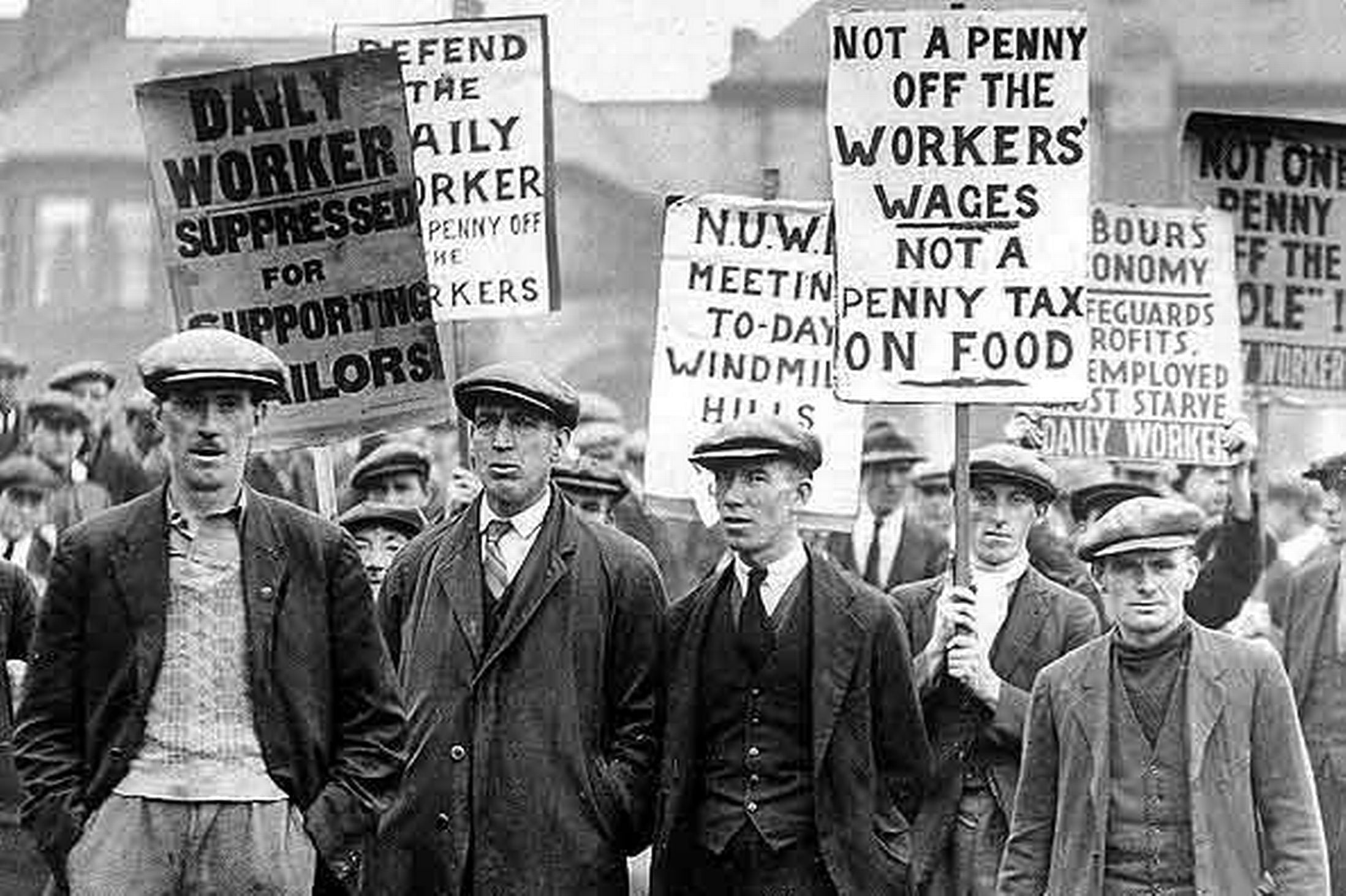

Cook coined the phrase: “Not a penny off the pay, not a second on the day”. This was a fine and decisive slogan to rally the miners and the working class. He argued that a “strike of the miners would mean the end of capitalism”.

Showdown

But even Cook, the best and most honest of these leaders, had no idea of what was involved in a general strike or how to organise it. For him it was just radical phraseology.

But even Cook, the best and most honest of these leaders, had no idea of what was involved in a general strike or how to organise it. For him it was just radical phraseology.

Because of the enormous indignation of the workers, the General Council, in reply to the refusal of the government to make concessions, threatened to call a general strike. The decision to strike was taken by 3,653,527 votes to 49,911 votes.

But behind the scenes, desperately, the TUC General Council appointed a committee to try to negotiate with the Conservative government. They were prepared even to accept a cut in wages for the miners as the price of a ‘negotiated settlement’.

In the Cabinet, the extreme right wing were exerting pressure for a showdown. Under this pressure, in order to break off negotiations, Baldwin used the pretext of the Daily Mail printers’ refusal to print a vicious attack on the unions and the miners.

After the TUC, with great difficulty, had succeeded in getting the printers reluctantly to print the editorial, they returned to the negotiations with the Prime Minister at Downing Street in the early hours of Sunday morning, where they were told “Mr. Baldwin has gone to bed and cannot be disturbed”.

Thus the ruling class deliberately provoked and precipitated the general strike as a means of defeating the workers, and to force them to accept a lower standard of living.

They got more than they bargained for! Hoping against hope for some sort of agreement, the TUC tremblingly had made no preparations for the strike whatsoever. But the magnificent capacity of the trade union and labour movement to improvise and organise came as a surprise to the government – and even to the union leaders themselves.

The first sections to be called out were the miners, dockers, seamen, and workers in transport, heavy chemicals, building (except housing), and the production of electric light and gas for industrial purposes.

The leaders of the seamen’s union refused to join the strike and organised blacklegging. But in spite of this, the strike was absolutely solid, and the rank and file of the seamen supported the strike.

There was initiative and improvisation from below. The trades councils in every area formed councils of action and strike committees. In some areas, the co-ops and Labour parties were involved; and in many less, the Communist Party also. Prominent leaders and individuals were co-opted to the strike committee.

In a sense, these were the elements of an alternative government appearing to confront the so-called ‘legal’ government.

Two submarines were used in the Thames for the purpose of providing light on the docks. But a warship which appeared in the Tyne was withdrawn after threats of the council of action to withdraw the safety and emergency men.

So powerful was the council of action on Tyneside that Kingsley Wood, the government representative, was compelled to negotiate with the council of action for permits for the transport of food.

Arrests

Non-unionists joined in the struggle and joined the unions in droves. In some cases, non-unionists even preceded the union workers in coming out on strike!

Non-unionists joined in the struggle and joined the unions in droves. In some cases, non-unionists even preceded the union workers in coming out on strike!

There were militant demonstrations and processions in all the main towns, often met with baton charges by the police. There were about three thousand arrests.

The brunt of the repression was felt by the then-revolutionary Communist Party. In preparation for the strike, twelve of their main leaders had been sentenced to imprisonment, safely out of the way on charges of ‘sedition’.

The Workers’ Weekly was raided, with their press immobilised by the removal of key parts of machinery. Up-and-down the country, Communists were also being arrested, along with thousands of workers, charged with incitement and jailed for terms of six weeks to two months.

The ranks of the workers were solid. Each day more were coming out. But the very success of the strike provoked more fear in the General Council than in the government.

On the eighth day, there was a callout of the engineers and other sections, although many were already coming out before the call. Thus on the eighth and ninth days, the strike was still expanding.

But behind the scenes, the General Council were ‘negotiating’ with Sir Herbert Samuel, the chairman of the Samuel Commission.

Without consulting the miners, the General Council informed Samuel that the miners would accept a cut in wages. But Samuel had no ‘official standing’ to negotiate for the government.

Yet, with no guarantees that the terms of the miserable agreement with Samuel – already a capitulation – would be carried out, the ‘lefts’ (as well as the rights) on the General Council agreed precipitately, and asked to see the Prime Minister, who accepted ‘surrender’ terms.

Why was the General Council prepared to capitulate to the government when the strike was actually developing, and when the ranks of the working class were becoming more solid every day? Every day that passed, there was a hardening of the attitude of the rank and file.

J.H. Thomas, the then ‘leader’ of the rail workers, put it in the crudest terms: “God help Britain in any challenge to the Constitution unless the government won.”

For the right-wing leaders of the TUC, a victory of the government was preferable to a victory of their own class. The ‘lefts’, meanwhile, had no alternative to offer when it was no longer a question of woolly phrases, but of the concrete reality.

The problem of power had been clearly posed. In addition to that, the organisation of the strike was entirely in the hands of the lower ranks throughout the country. The General Council, in effect, was a passive recipient of the accomplished actions of the strike committees. Each day that passed saw a strengthening of the power, initiative and resource of the committees in the localities.

Panic

The spectre that haunted the General Council, giving them sleepless nights, was the possibility of their replacement in the struggle by the lower ranks, who would threaten to bypass them.

The spectre that haunted the General Council, giving them sleepless nights, was the possibility of their replacement in the struggle by the lower ranks, who would threaten to bypass them.

In his book on the general strike, Julian Symons, not at all a revolutionary, nevertheless was compelled to remark:

“They (the General Council) were not rash but feebly timid; they hoped for the collaboration of their opponents and never really trusted the mass of their supporters. They feared the consequences of complete victory more than those of a negotiated defeat.” (My emphasis)

“The General Council was torn by conflicting desires. First, it wanted to make the strike effective; second, it wanted to make certain that control of it did not pass into the hands of revolutionary agitators.” (My emphasis).

He quotes Thomas:

“What I dreaded about the strike, more than anything else, was this; if by any chance it should have got out of the hands of those who would be able to exercise some control, every sane man knows what would have happened…That danger, that fear, was always in our minds, because we wanted, at least, even in this struggle to direct a disciplined army.”

In their panic to call off the strike, at a time when it was expanding and growing, the union leaders did not even put forward the elementary demand in every strike that there should be no victimisation, and that every worker must be taken back.

In his speech on the radio, Baldwin implacably declared that there were no ‘conditions’, and that it was unconditional surrender in the strike. The scabs taken on must have first claims on the jobs. This was a signal for the employers to try and wreck, weaken, or destroy union organisation.

The rank and file had greeted the decision to call off the strike with indignation and resentment. They felt themselves betrayed by the leadership. And it was the local leadership and this rank and file who were to save the situation from developing into a rout.

When they heard of the conditions being offered by the employers, the rail workers, dockers, engineers, and other sections renewed the strike. In fact, two days after the general strike had been officially called off, there were 100,000 more on strike!

The leaders of the different unions then issued instructions to their members to come out on strike – which they were already doing – and not to accept any terms in relation to wages and conditions that were worse than those that existed before the strike. There would be no going back, unless there was no victimisation by the employers and the government.

Faced with the veritable fury of the working class and the possibility of large-scale clashes in the localities, Baldwin then came forward in his hypocritical role of a ‘conciliator’. He broadcast that the employers must take back the workers on the old terms, and that he would not countenance any attempt to break up the unions. The employers consented.

The railway unions negotiated an agreement with the railway leaders that there would be no victimisation. But they refused to take back any worker who was guilty of ‘intimidation or violence’. The printers agreed not to hold any more meetings in work time, and on this concession the printers went back.

Thus, what had begun as a tremendous movement ended up in defeat, and was only saved from rout by the solidarity and militancy of the local leaders and of the rank and file.

The working class was caught completely by surprise by the betrayals of the ‘left’, as well as those of the right-wing leaders. This was especially so with regard to the Communist Party, where at that time – not only the rank and file, but also the leadership – were endeavouring to create a revolutionary party.

Surprise

Why then were they disarmed and unprepared by these events? They were caught by surprise because of the policy of Stalin and the Russian leaders, who dictated the policy of the then-Communist International.

Why then were they disarmed and unprepared by these events? They were caught by surprise because of the policy of Stalin and the Russian leaders, who dictated the policy of the then-Communist International.

The Anglo-Russian Committee, they had been taught, was a mobilisation of the British and Russian trade unions to fight war. They took at face value the speeches of the ‘left’ leaders; at least they were instructed by Moscow to do so, and accepted the policy.

In the strike, the rank and file of the party had naturally been among the most active sections of the workers. After the immobilisation of their press, they reacted by bringing out duplicated papers with a total circulation of over 100,000.

But an examination of these papers indicate that they gave no perspective, either in their speeches or in writing, during the strike. There was no guidance; no perspective for the struggle, beyond support for the strike and support for the General Council.

From the first day, the General Council had issued a statement to the ranks to “trust the leadership”. During the course of the strike, there was not a single word of warning in all the agitation and propaganda of the Communist Party. They were caught completely unprepared and on one foot.

Had they been politically prepared and armed, even in those days, they would have undoubtedly won over hundreds of thousands of the best workers.

Betrayal

People learn far quicker under fire and in the heat of events – especially the active layers of the working class. But the howl of the Communist Party of ‘betrayal’, which was entirely unforeseen and unprepared for, came too late to have any effect except to demoralise their own ranks.

People learn far quicker under fire and in the heat of events – especially the active layers of the working class. But the howl of the Communist Party of ‘betrayal’, which was entirely unforeseen and unprepared for, came too late to have any effect except to demoralise their own ranks.

They had been taught not to offer any real criticism of the ‘left’ leaders, or even of the General Council, whom they saw as leaders of the struggle. They did not pose a single idea beyond the winning of the strike, until it was too late.

Moreover, they had not prepared in any way for this inevitable turn of events, given the situation. The fact is, without a Marxist perspective and Marxist understanding, the ‘left’ leaders had no other course to take, except to join in the betrayal with their right-wing colleagues.

The working class was caught completely unprepared by the betrayal from the top. Instead of enormous gains – which should be inevitable in a period like that, on the basis of correct policies, strategy and tactics – the back of the Communist Party was broken. The Minority Movement disappeared.

By 1927, the trade union leaders, ‘lefts’ and rights, having contemptuously cast aside the Anglo-Russian Committee, by breaking off relations, had turned to ‘collaboration’ with the employers in the Mond-Turner discussions. They could do this because of the mood of apathy and indifference which pervaded the trade union movement.

What was necessary in 1926 – and is necessary today – is a friendly but implacable criticism of the left leaders in the unions: a skilful criticism of the woolliness, the vagueness, and inconsistency of the lefts, and of their failure to present the issues in sharp and clear class terms.

In this new epoch of inflation, it is either/or: either a struggle for the transformation of society; or an inevitable capitulation to the interests of big business. In 1925 to 1926, it was the struggle against deflation.

After the collapse of the general strike of 1926 – too late – the Communist Party tried to make a change and criticise the role of the left union leaders, theoretically and practically.

Palme-Dutt, their leading ‘theoretician’, quoted the criticism of the left leaders made in 1924! Not a sentence, not a word could he find in the material published by the Communist Party in 1925, or 1926, explaining in theoretical or practical terms the role of the left.

However, it would be instructive to quote the strictures on the left leaders when it was too late.

In the July 1926 Labour Monthly, Palme-Dutt wrote in his ‘Notes of the Month’:

“The experience of the general strike has shown that the question of leadership is a life and death question for the workers and to neglect it or treat it lightly is fatal…The enemy within in fact is most dangerous…

“The old reformist myth that it is only the backwardness of the workers which is the obstacle to the progressive intentions of the leaders is smashed. Only a couple of weeks before the general strike, Brailsford (ILP leader) in his answer to Trotsky, was expressing polite incredulity at Trotsky’s statement that the workers in Britain were already in practice far in advance of the ILP leaders, and holding it up as a glaring example of Russian ‘ignorance’ of British conditions. After the general strike, the statement appears as the merest commonplace.”

On the right-wing leaders, he comments (at the 13th hour):

“Having ensured its defeat, they come forward to proclaim the final failure of the general strike weapon, and even that they knew its folly all along. That is the typical role of social democracy.

“On the other hand, it was conspicuously obvious that the left wing (my emphasis) which had developed as an opposition tendency in the trade unions during the past two years around the personalities of certain leaders on the General Council such as Hicks, Bromley, Tillett, Purcell and others, completely failed to provide any alternative leadership during the crisis and in practice fell behind the right wing. This is an extremely significant fact and it is all important.”

Opportunism

Palme-Dutt – not sure at that time which way events in Russia were going to move – even quoted Trotsky, writing before these great events and warning of the role of the lefts. Palme-Dutt quotes this, alas, when the working class had been defeated, and without honestly criticising the policy of the Communist Party in the months and years before the general strike:

Palme-Dutt – not sure at that time which way events in Russia were going to move – even quoted Trotsky, writing before these great events and warning of the role of the lefts. Palme-Dutt quotes this, alas, when the working class had been defeated, and without honestly criticising the policy of the Communist Party in the months and years before the general strike:

“The trade union left wing was not able to provide any alternative to the right wing because the trade union left wing had not yet in practice reached any basic difference from the right. The trade union left wing was the reflection of the important and growing tendencies and aspirations within the working class, of a growing opposition to the opportunism and betrayals of the existing leadership, and the demand for a policy of solidarity and class struggle.

“But these tendencies and aspirations were not translated into any positive programme and proposals, any organised policy and action, any recognition of the alternative to opportunism, or any clearly formulated tactics and methods of struggle. Therefore, the phrases of solidarity and class struggle inevitably became air without substance; in practice the left wing leaders were impotent and therefore became the prisoners of the right wing, who at any rate had a positive polish, although a policy of surrender and co-operation with the bourgeoisie.”

Palme-Dutt wrote in the Labour Monthly again:

“In a recent article, Trotsky has pointed out that the more revolutionary in principle a resolution was at Scarborough, the more easily it was carried; but the closer it came to an even elementary task of action, the stronger was the opposition.

“International unity with the Communist-led trade unions of Russia was carried unanimously by the same delegates who a few weeks later were voting for the expulsion of Communist trade unionists at home from the labour movement…But the formation of factory committees, and even that in principle, was only carried by 2,456,000 to 1,218,000…Thus the move to the left was in practice a show move to the left reflecting the undoubted movement of working class opinion but sterilised and neutralised by the skilful opportunist leadership who allowed no change in policy.

“In consequence, the sequel of Scarborough by Liverpool, with its victory of extreme reaction and the conspicuous collapse of the left wing, was not a contradiction of Scarborough but its completion.” (p.518, August 1926).

In an article by Jack Tanner in Labour Monthly, he declared that the mood amongst trade union activists was that:

“There is a feeling now that it would have probably been better if they had ‘trussed ’ them! (In reference to the General Council leaders’ appeal to ‘trust us’)…after the first week this outlook (merely to fight in defence of the miners) changed somewhat. They were in the fight and up against all employers and the state. They began to realise that and were prepared to continue.”

Too late, after the strike had been called off, the Communist Party sent a telegram to all parts of the country, emphasising the following points:

1) The General Council, despite previous promises and of unanimous demands of workers, has ceased the struggle against lower wages without receiving any kind of guarantee from government.

2) That is treachery, not only in relation to miners but all workers.

3) While the right wing of the General Council and Labour Party has exhibited utmost energy, the left wing has tolerated defeatist agitation and not protested against this treacherous decision.

Thus, when it was too late, the Communist leadership started explaining the real issues. This is the opposite of the method of Lenin.

Today’s situation

The changes in the situation since 1926, in objective terms, are all favourable to the working class. The government has not got the social reserves they had in 1926.

The changes in the situation since 1926, in objective terms, are all favourable to the working class. The government has not got the social reserves they had in 1926.

Once again, rapidly increasing prices of most necessities will anger and incense the working class. Consequently, in the months ahead there will be industrial explosions. In that situation there is the possibility – not at all the certainty – of an all-out general strike against the Tory government.

However, today’s tiny Communist Party has not learned anything from the experience of the 1926 general strike. To their leaders, this is a closed book. Their programme – industrially and politically – is the same as the programme of the left leaders. Consequently, far from differentiating themselves, they make strenuous efforts to appear exactly the same!

In none of their literature is the problem of power posed. On a higher historical level, they repeat in a cruder form the mistakes of the Communist Party in 1925 and 1926. But this is because they have long ago ceased to be Marxists.

Marxism tries to generalise the experience of the working class in the past, in order to learn the lessons and prepare the workers for present and future struggle. That is the essence of the Marxist method, as developed by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky.

Thus, for industrial militants, what is most needed above all is political clarity. For activists to immerse themselves purely in the industrial struggle is to prepare terrible setbacks.

A clear perspective and understanding are necessary, if the movement is not to move forward blindly to defeat. The elemental movement of the class will take place in any case. But to guide it to victory, the active layers must clearly understand the problems posed.