Beginning on the 4th May, the 1926 General Strike shook the ruling class of Britain to its foundations. Lasting for nine days, the strike showed the enormous power and solidarity of the working class. James Kilby examines the lessons from the General Strike for today, as the crisis of capitalism deepens and the class struggle intensifies.

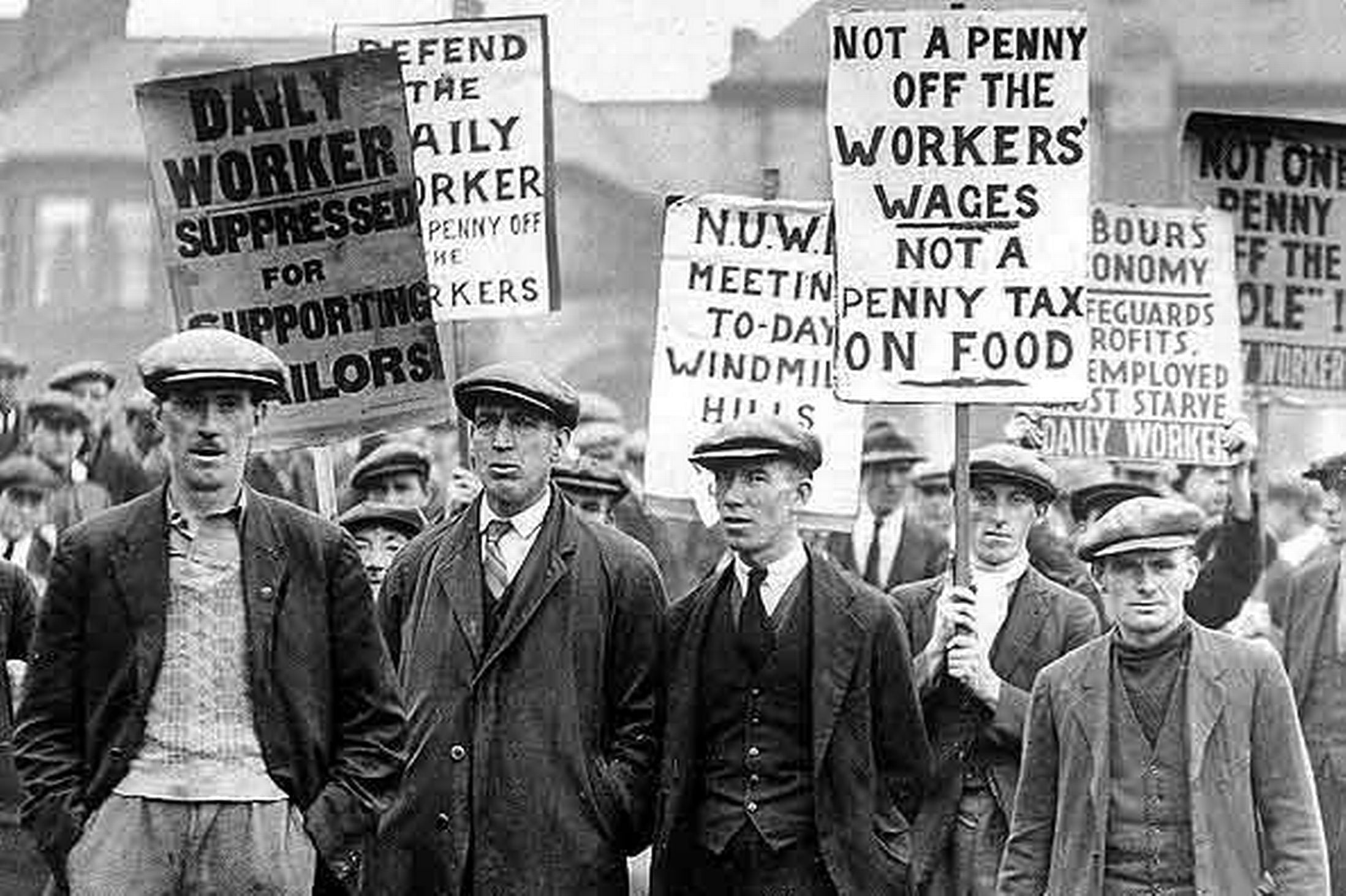

Beginning at one minute to midnight on the 3rd May, the 1926 General Strike shook the ruling class of Britain to its foundations. Lasting for nine days, the strike showed the enormous power and solidarity of the working class. 4 million trade unionists – out of a total of 5.5 million – responded to the TUC’s call to halt work. Despite no real preparation by the TUC leadership, workers organised – through their own initiative – strike committees up and down the country. Nothing moved without the workers’ permission.

However, despite the strike growing stronger and stronger, the TUC leadership did everything they could to bring the strike to an end, resulting in a crushing defeat. The Communist Party failed to play the revolutionary role required by it, and sowed confusion amongst the advanced workers. The betrayal of the TUC “Lefts” came like a bolt from the blue, and set the movement back for years.

As the crisis of capitalism deepens, we will see the return of general strikes across the world. In Britain, with workers facing austerity and attacks across the board, the demand for a general strike is clearly a necessary one. It is therefore vital that we study the lessons of the 1926 General Strike, in preparing ourselves for such titanic events in the future.

Showdown looming

The explosive situation that gave rise to the strike had been prepared for years in advance. British capitalism had emerged from the First World War considerably weaker with respect to that of the USA. By the mid 1920s, the German coal industry was also outstripping that of Britain, which relied on antiquated machinery and techniques. Rather than investing to raise productivity, the British ruling class responded by attacking wages and conditions.

In 1925, the Tory Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, announced at a meeting with the Miners’ Union: “All the workers in this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet”. The miners in particular were expected to accept a 13% reduction in their wages to starvation levels, and to work an extra hour each day. Feeling the pressure from below, the Trade Union Congress (TUC) responded by threatening a general strike.

Unprepared for such a showdown, the government retreated temporarily, in order to prepare for an all out struggle. A subsidy was given to the coal barons for nine months, whilst the Samuel Commission was established to examine the industry. During this time, the government prepared a scab army by the name of the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS). This included Special Constables and fascists, organised with its sole purpose to confront the working class.

After nine months of preparations, the Samuel Commission recommended the same policy that the miners and trade unionists generally had rejected – that of increased hours and reduced wages. With the labour movement swinging to the left after the coming to power of the Tories in 1924, the General Council of the TUC was under enormous pressure to act. Workers in all industries correctly saw the miners struggle as their struggle. If the miners were defeated, others would be soon to follow.

On May 1st 1926, the decision to strike was carried by 3,653,527 votes to 49,911 votes at the TUC. However, behind the scenes, the General Council, desperate to avoid a struggle, appointed a committee to try to negotiate with the government.

The General Council were even prepared to accept a reduction in the miners’ wages, in order to reach a “negotiated settlement”. However, the right wing government was determined for a showdown, and used various pretexts in order to call off negotiations. Their aim was to defeat the workers, in order to restore profitability for the ruling class and hold onto their share of the world market.

All Out!

On the morning of 4th May, millions of workers responded to the call to strike. The first sections to be called out were the miners, dockers, seamen, plus workers in construction (except housing and hospitals), transport, heavy chemicals, and the production of electric light and gas for industry. Although the leaders of the Seamen’s union refused to join the strike, the rank and file joined in, and thus the strike was solid.

The TUC leaders, believing that they would reach a settlement with the government, had made no preparations for the strike. To their surprise, and to the shock of the ruling class, the workers showed their magnificent capacity to improvise and organise from below.

Trades Councils in every area formed Councils of Action and strike committees. Nothing could happen without the permission of the working class. The Councils organised picketing, communications, permits for the supply of basic goods, and even workers defence corps to protect against the violence of the state. As the strike developed further into a struggle against the government, the Councils of Action developed increasingly into organs of self-government. In reality they were the embryos of workers’ power.

Unstoppable power

Militant demonstrations took place in all the main towns and cities. Clashes with the police were commonplace, and thousands of workers were arrested and imprisoned.

Alarmed at the power of the working class, the government sent battleships to the Mersey, the Clyde, and off the coast at Swansea and Cardiff. Two battalions of the army were dispatched to Liverpool, and Hyde Park in London was turned into an armed camp. Despite these attempts to intimidate workers, the strike was unstoppable, with more and more workers coming out each day, including even unorganised workers.

On the eighth day of the strike, the engineers and other sections of the working class were called to join the action. In many cases, workers were already out on strike before being called, such was the mood for solidarity across the working class.

TUC betrayal

Rather than fearing the resistance of the ruling class, who proved impotent in the face of millions of organised workers, the General Council of the TUC were more terrified of the revolutionary implications of the strike. The government spared no time in declaring the strike a challenge to the constitution.

Rather than fearing the resistance of the ruling class, who proved impotent in the face of millions of organised workers, the General Council of the TUC were more terrified of the revolutionary implications of the strike. The government spared no time in declaring the strike a challenge to the constitution.

The right wing members of the General Council such as Jimmy Thomas, however, rejected this claim, falling over themselves to downplay the militancy of the strike and deny that it was political. They insisted, instead, that it was merely a dispute over wages, terms and conditions. Thomas even went so far as to declare that if the strike was a challenge to the constitution, then “God help us, unless the government won”. The leadership of the Labour Party, right-wingers such as Ramsay MacDonald, shared the same view.

A general strike inevitably poses the question of power. Either it will lead to the conquest of power by the working class, or a severe defeat for the workers.

Since even the “Lefts” on the General Council lacked any perspective of taking power and overthrowing capitalism, they too rejected the political nature of the strike. They did everything they could to “compromise” with the government, i.e. restore order for the capitalists. It is examples such as this that led Leon Trotsky to assert that “betrayal is inherent in reformism”.

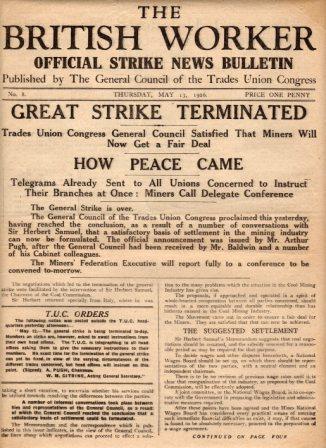

Behind the scenes, the General Council completely capitulated to the government, accepting a reduction in the miners’ wages, with no guarantees against victimisation. Baldwin announced on the radio that there were “no conditions”, and that the TUC had accepted this unconditional surrender.

This news came as a complete shock to the workers, who could feel the enormous power they wielded during the strike. In response to the sell out, the railmen, dockers, engineers, and other sections renewed the strike, in order to prevent it from ending as a complete rout. Thus two days after the strike had been officially called off, over 100,000 more workers had joined the strike!

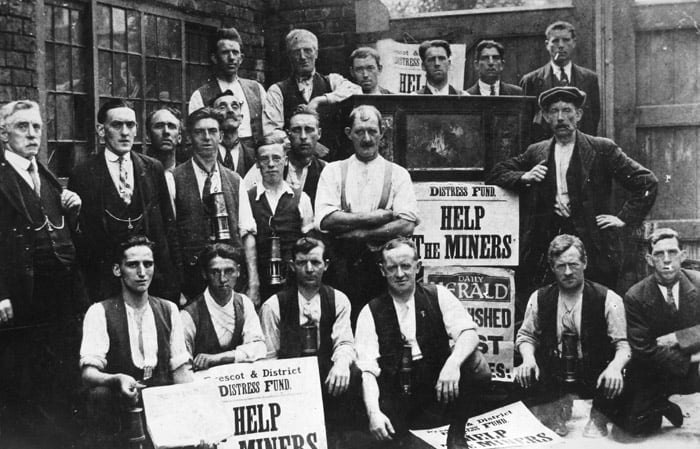

Faced with this growing anger, Baldwin announced that the employers must take back the workers without victimisation. With the back of the strike broken by its own leadership, workers returned to work in one section after another. The miners held out for another few months, but eventually were starved back to work.

Communist Party mistakes

Although the most conscious workers expected the betrayal from right wing leaders such as Thomas – and MacDonald – the betrayal of the “Lefts” on the General Council such as Purcell, Hicks, and Cooke came as a complete surprise.

Responsibility for this lies with the mistaken tactics of the Communist Party, who, under orders from Moscow, failed to offer any criticism of such leaders. Instead, they gave revolutionary illusions in such leaders by maintaining the Anglo-Russian Committee: a “united front” between the revolutionary trade unions in Russia, and the so called “left” trade union leaders in Britain. They failed to provide any perspective for a struggle beyond the limits of the strike.

Had the Communist Party prepared the rank and file for such a betrayal, they could have significantly increased their influence in the trade unions, even in the event of the defeat. Instead, the CPGB could not escape their share of the blame for the sell-out, and therefore suffered as part of the general demoralisation that followed.

Lessons for today

With capitalism in crisis on a world scale, huge anger is building up against the ruling class everywhere, including in Britain. Workers and youth are being forced to pay for the crisis through attacks to their jobs, wages, terms and conditions, and pensions. This is a finished recipe for class struggle everywhere.

Feeling the pressure from below, the TUC passed a resolution in 2012 to look into the “practicalities” of organising a 24-hour general strike. Yet despite years of considering the “practicalities”, nothing came of this, since the TUC leaders are terrified of unleashing a real struggle. This was confirmed in 2013, when Len McCluskey led a complete capitulation over the lock-out at the Grangemouth oil refinery, rather than mobilise workers to confront the bosses.

Despite this lack of leadership, pressure for a general strike will not go away, as has been evidenced by the junior doctors’ struggle. Already the teachers’ union, the NUT, has expressed its desire for joint action against the government. At a recent rally in support of the junior doctors’, Mark Serwotka, the general secretary of PCS (the civil servants’ union), also called for a “national day of action” in support of the striking medics and in defence of the NHS. With workers everywhere under attack, pressure will build to link up separate struggles with coordinated action.

In contrast to 1926, a general strike today would be immeasurably more powerful. In 1926, formerly middle class layers such as teachers, civil servants, doctors, and students attempted to scab the strike. Decades later, these sections of the workforce have been proletarianised and are now organised in some of the most left wing unions. Even if Britain’s largest union, Unite, called out all its members, it would bring the country to a standstill, given that Unite organises key power, transport, and logistics workers. Added to that, with the power of the rest of the trade union movement, such a strike would be unstoppable, if led by resolute leaders.

Given the numerous strikes by many unions over the past period, we support the demand to take such action to the next level with a 24-hour general strike against the Tory government. Such a strike would galvanise the mood of the working class, and give it confidence to go forward in struggle. It is on the basis of big events such as these that workers feel their own strength, and that their consciousness as a class in conflict with the bosses develops.

As the class struggle heats up in the future, the question of an indefinite general strike may well emerge. As the 1926 General Strike showed, it must be prepared for with a leadership that is determined and willing to take power. Despite all the magnificent capacity for organisation; despite creating the embryos of workers control: unless the working class has a leadership that is prepared to break with the bankers, capitalists, and landlords, a general strike that does not go all the way will end up with a defeat.

The best way that we can commemorate the 1926 General Strike is by taking these lessons on board. 1926 may represent the first General Strike in Britain, but it is unlikely to be the last. Only by struggling to build the Marxist Tendency within the labour movement will we develop a leadership capable of taking future struggles to victory.