The Anglo-Russian Trade Union Committee was established in April 1925. It was seen as an attempt to heal the split between the reformist and the communist trade union federations.

This initiative followed the visit of a number of British trade union leaders to the Soviet Union in late 1924 which discussed closer unity with their Russian counterparts. After a joint declaration a trade union Committee was established. This bridge-building at the top however had certain consequences.

In the end, the Anglo-Russian Committee was a failed attempt to build communist influence in the British trade unions in the mid-1920s. This opportunist policy directly contributed to illusions in the role of ‘left’ trade union leaders, and the marginalisation of the British Communist Party.

Communist influence in trade unions

In the early 1920s, as part of the turn towards mass work, Communist parties around the world directed their attention towards building influence in the trade unions.

In July 1921, the Communist International (Comintern) declared:

“The principal task of all Communists over the next period, is to wage a firm and vigorous struggle to win the majority of the workers organised in the trade unions…The true measure of the strength of a Communist Party is the influence it has on the mass of trade-unionists.”

However, in working within trade unions or other organisations of the working class, the Comintern insisted that:

“Whilst supporting the slogan of maximum unity of all workers’ organisations in every practical action against the capitalist front, Communists cannot in any circumstances refrain from putting forward their views, which are the only consistent expression of the interests of the working class as a whole.”

For the Communists, it was necessary to take their ideas into the mass organisations of the working class. They did not cut themselves off from the class struggle or comment from the sidelines, but participated in it at every opportunity. In doing so they worked to distinguish themselves as the most radical class fighters, and to build up support for Communist policies.

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was formed in 1920. It was a small group of a few thousand serious class fighters. It took some years to establish its methods. But in August 1924 the party launched the National Minority Movement (NMM) in the trade unions.

The NMM organised rank-and-file trade unionists around militant policies for the unions. Within a short period of time, it hugely expanded Communist influence in the trade unions, and was a great example of the methods advocated by the Comintern.

One of the NMM’s most notable early successes was the election of A J Cook as the leader of the Miners’ Federation in 1924. He was supported by the NMM, stating that he was “a disciple of Karl Marx and a humble follower of Lenin” and that he supported the Communist Party because “I agree with nine-tenths of its policy”.

Degeneration and short-cuts

However, by the middle of the decade the outlook of the Comintern leadership, based in Moscow, was changing. In October 1923, a communist-led uprising in Germany had been defeated. This marked a turning point in the attitude of a layer of the Russian leaders. Coupled with this was the death of Lenin in January 1924.

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 had successfully overthrown capitalism in Russia. But that revolution remained isolated in a relatively undeveloped country. All attempts at revolution elsewhere had failed. Meanwhile, the Russian workers and peasants had been dragged through a world war and a civil war, and were completely exhausted.

The consequences of this isolation and exhaustion in a backward country was the growth of bureaucracy within the state and party. Stalin became the figurehead of this bureaucratic reaction, who, along with Zinoviev and Kamenev, formed a ruling troika.

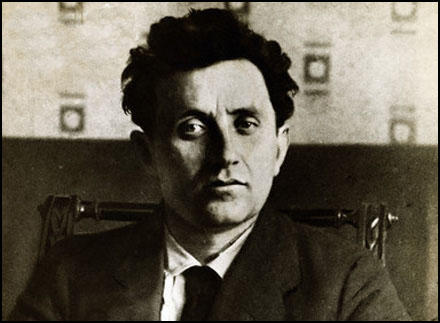

Zinoviev in particular preferred to look for easier paths and short-cuts towards world revolution.

In Britain, the Communist Party remained relatively small. The idea of building up this party into a force for revolution seemed impractical to Zinoviev. He therefore began to look for other avenues.

This brought Zinoviev’s outlook into line with that of Mikhail Tomsky, who had been the leader of the Russian trade union movement since 1920. Although a Bolshevik, Tomsky had always been on the right of the party. Both looked towards building links with the tops of the trade unions in the West.

In early 1924, Tomsky and Zinoviev spotted what they thought was an opportunity in Britain. The first Labour government took office on 22 January 1924. It gave diplomatic recognition to the USSR for the first time on 1 February 1924.

Therefore, in May 1924, a delegation of Soviet diplomats was sent to London. The delegation included Tomsky, who struck up a friendly rapport with the left reformist trade union leaders, declaring to them over dinner that “transient political differences” would continue to separate British and Russian trade unionists, but that “trade unionists are the most practical and sensible people in the world”, and so differences would be of a purely superficial character.

By the summer of 1924 at the fifth congress of the Comintern, Zinoviev was suggesting that a struggle by the Communist Party to win over the workers might not be necessary:

“In Britain we are now going through the beginnings of a new chapter in the labour movement. We do not know exactly whence the Communist mass party of Britain will come, whether only through the Stewart-MacManus door [leading figures in the CPGB] or through some other door.”

The “other door” to which Zinoviev referred was the left reformist trade union leaders with whom Tomsky had got on so well in London.

This was a radical departure from the experience of the Russian Revolution, which showed that without the painstaking work of building a Bolshevik party over many years the revolution would never have been possible.

There had been no quick methods in building the Bolshevik party. While the Mensheviks did agree deals with the liberals, the Bolsheviks patiently strengthened their forces through discussion and participation in the class struggle. In the end it was the Bolsheviks alone who were capable of leading the workers to the conquest of power in Russia.

With the death of Lenin in January 1924, it was left to Trotsky to defend the lessons of Bolshevism against Zinoviev’s search for “another door”. In 1924 he said:

“It is true that the British trade unions may become a mighty lever of the proletarian revolution; they may, for instance, even replace workers’ soviets under certain conditions and for a certain time. They can, however, fill such a role not apart from a Communist Party and certainly not against the party, but only on the condition that Communist influence becomes the decisive influence in the trade unions.”

Formation of the Anglo-Russian Committee

Despite Trotsky’s warnings, the slide away from Bolshevism in the Comintern continued. On 27 April 1925, Stalin announced the policy of “socialism in one country”, which confirmed the abandonment of revolutionary perspectives in other countries and reflected the conservative interests of the bureaucratic elite.

In Britain, this diplomacy focused on the trade union leaders and took the form of mutual back-slapping and sycophantic schmoozing.

In September 1924, Tomsky attended the Trade Union Congress (TUC) in Hull. Walter Citrine, the assistant general secretary of the TUC at that time, wrote in his memoirs that all 724 delegates of the Congress were “on the tiptoe of expectation”.

The standing ovation at the end of Tomsky’s speech was described as “the greatest éclat ever known in a labour conference”. The authority of the Soviet Union as well as its leaders was very high in the eyes of the British working class.

In turn, the Comintern leaders promoted the British left trade union leaders as great revolutionaries. Zinoviev stated that Anglo-Russian trade union co-operation was “the greatest hope of the international proletariat”.

At a reciprocal visit of British trade union leaders to the USSR in November 1924, they addressed the Sixth Trade Union Congress of the Soviets. At the end of the proceedings, delegates rushed the stage and threw both Tomsky and Purcell, the leader of the British delegation, high into the air in celebration.

This chummy relationship was consummated in April 1925 with the formation of the Anglo-Russian Committee of British and Soviet trade union representatives, established to promote trade union unity.

Trotsky supported the formation of the Anglo-Russian Committee, but not unreservedly. He explained that the committee of communist and reformist leaders must be an auxiliary to building communist influence in the ranks of the British trade unions.

But this was not the outlook of the other Comintern leaders. As Trotsky explained in 1928: “The point of departure of the Anglo-Russian Committee…was the impatient urge to leap over the young and too slowly developing Communist Party.”

The British Communist Party

The British trade union leaders on the Anglo-Russian committee had no real involvement in the NMM or engagement with the Communist Party. Their ‘radicalism’ was strictly limited to the international sphere, to events far away. When it came to the British class struggle that radicalism soon evaporated.

In fact, these trade union leaders were actively hostile to the communist-led NMM. The TUC General Council asked Tomsky not to attend or even send Soviet delegates to NMM meetings. Scandalously Tomsky agreed to this. He preferred friendship with the reformist trade union leaders, above strengthening the position and work of the Communist Party.

Following the Comintern’s lead, the CPGB leaders did not see their role as trying to win a decisive influence over the mass of workers, preferring to leave things to the ‘left’ trade union leaders.

J T Murphy, one such leader, summed up this outlook in 1926 when he wrote:

“Our party does not hold the leading positions in the TUC. It is not conducting the negotiations with the employers and the government. It can only advise and place its forces at the service of the workers – led by others. To entertain any exaggerated views as to the revolutionary probabilities of this crisis and visions of a ‘new leadership arising spontaneously in the struggle’ is fantastic.”

Similarly in 1925, R P Dutt, another CPGB leader said that: “In the present stage the language of the left trade union leaders is the closest indication of the advance of the British working class to revolution.”

This was the attitude which prevailed among the leaders of the Communist Party throughout 1925 and 1926. Despite the earth-shattering industrial struggles which took place, they felt that the Communists had no real independent role to play.

Preparing for a general strike

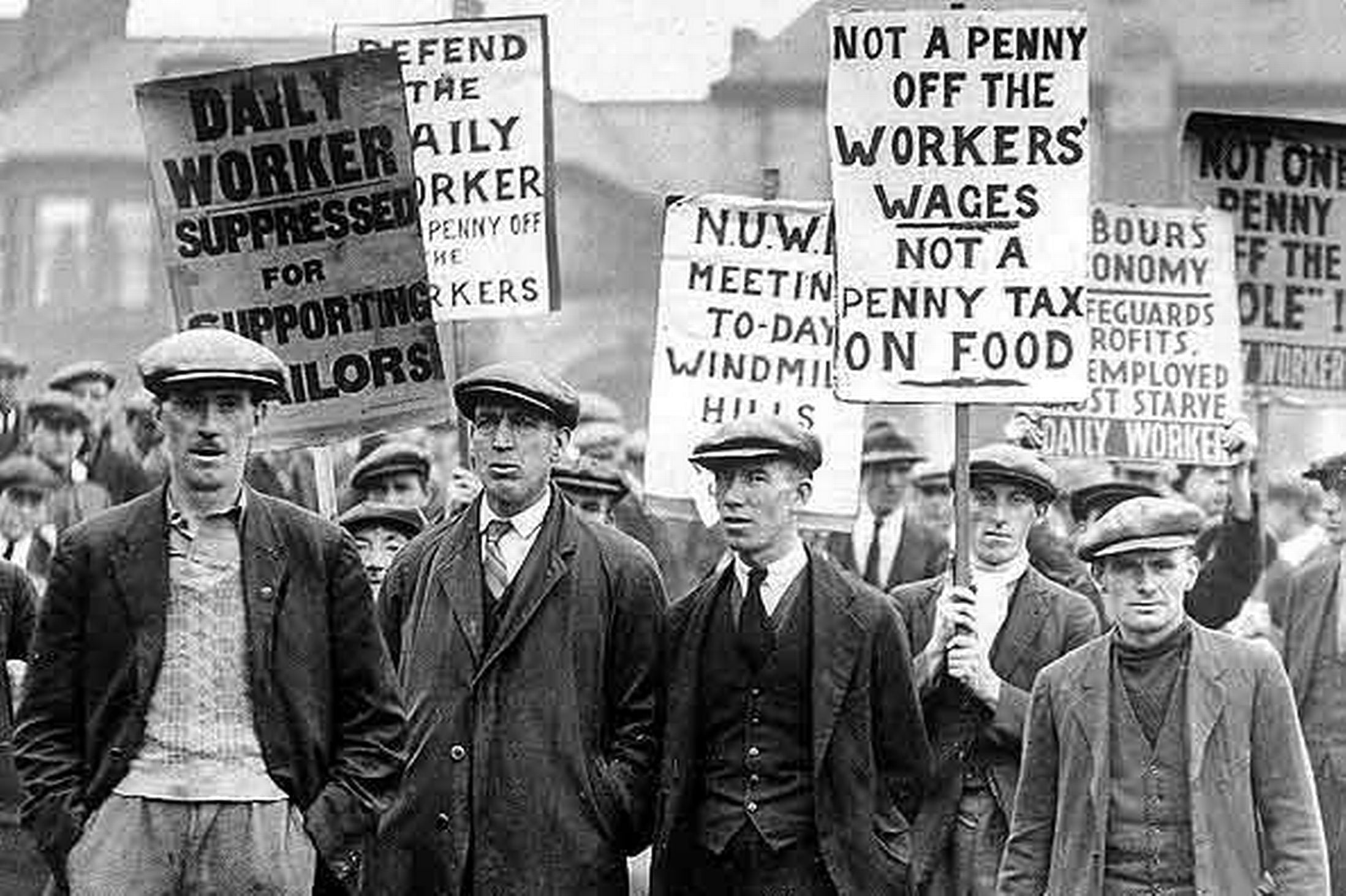

In July 1925, rank-and-file militancy forced the leaders of the trade unions in Britain to stand their ground in defence of coal miners against attacks by the government and the bosses. The employers backed down and the victory was dubbed ‘Red Friday’.

But this was a temporary postponement of the battle. The government promised to revisit the question less than a year later, in May 1926, when a ‘Coal Commission’ would make its recommendations. Instead of mobilising for the struggle to come, the trade union leaders dismantled the very movement which had pushed them to defy the government.

The Scarborough Congress of the TUC in September 1925 was very left-wing, adopting many NMM policies and positions. Once again it welcomed Tomsky, who carried the authority of the Russian Revolution, with open arms.

But the Scarborough Congress saw the return of right-wingers to the TUC General Council, after the defeat of the Labour government at the election in October 1924. Those right-wingers who had resigned from the General Council to serve in the government now returned.

The Chair of the TUC also changed from the left-winger Bramley, who died in October 1925, to the right-winger Citrine.

The 1925 Labour Party conference in Liverpool was held immediately after the TUC. The Labour Party leaders pushed through a ban on communists being members of the Party.

Meanwhile, the left-wing trade union leaders, who sat alongside the Soviets on the Anglo-Russian Committee, did nothing to resist such a move. Rank-and-file Communist Party members were hung out to dry by these ‘lefts’.

Meanwhile A J Cook, the NMM-backed miners’ leader, campaigned for the TUC leaders to get ready for a serious struggle to defend the miners, but his appeal fell on deaf ears.

Tom Bell was a leader of the CPGB at the time. He recalled:

“The Labour leaders made no effort to prepare for action. They lulled the trade unions into a false sense of security by encouraging reliance on the findings of the Coal Commission. At the same time in many places it was tacitly assumed that secret preparations were being made by the General Council. The fact that there was a left wing on the Council (comprising Purcell, Swales, Hicks, Tillett and Bromley) lent colour to this idea.”

In fact, no preparations were being made by these ‘left-wing’ trade union leaders.

Ignoring the problems

The CPGB could sense the looming danger. The government was preparing for a showdown with the miners, while the reformist trade union leaders were twiddling their thumbs.

The Communist Party urgently appealed to the Comintern for concrete and practical guidance, but none was forthcoming.

After the main leaders of the CPGB were imprisoned in October 1925, it was left to an inexperienced layer to run the party. The British delegates to a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Comintern in February 1926 painted a worrying picture of the party.

One delegate, George Hardy, explained that the formation of NMM factory groups was, as yet, “something which we have to tackle”. Another, Aitken Ferguson, described the role of the NMM as no more than “to bring pressure to bear upon the reactionaries and to stiffen up the hesitating and wobbly elements”.

Clearly the British Communist Party had neither the means to, nor the perspective of, developing a serious alternative to the head-in-the-sand strategy of the trade union leaders, when it came to the coming industrial conflict.

Instead of rectifying this problem, the Comintern leaders ignored it. At the close of the Comintern Executive meeting Zinoviev said that the miners’ struggle wasn’t particularly important anyway. It would, he said, “conceal in itself only the embryo of the approaching colossal social struggle”.

This dismissive attitude was partly because the Comintern leaders were looking in a different direction. In early 1926, the prospect of trade and diplomatic relations with Britain opened up. Progress was made in Franco-Soviet trade agreements, and in April a German-Soviet treaty of neutrality was signed.

All this put pressure on Britain to accept trade and diplomacy with the Soviet Union so as not to get left behind. Austen Chamberlain, the foreign secretary, said that “a hint of the glad eye [towards Russia] might be useful at home and abroad”.

When the focus of Soviet policy was securing its own borders, this left little interest in potential revolutionary developments in Britain.

The Comintern was deliberately seeking to downplay the prospects for revolution in Britain. It didn’t understand the significance of the miners’ dispute, and was taken by surprise by how it developed. It found it more convenient to follow the lead of the British trade union leaders in characterising the struggle as a purely economic dispute.

Karl Radek, a Comintern leader, commented on the general strike: “Make no mistake, this is not a revolutionary movement. It is simply a wage dispute.”

Faced with the relative indifference of the Comintern, the British communists drew up a plan for reorganising the NMM. But this wouldn’t take place until June – after the Coal Commission’s report and the planned showdown between government and miners.

The NMM conference met in March 1926. But instead of making practical preparations it simply condemned the capitalist offensive against the workers. At the same time it sent out instructions to Councils of Action, made up of rank-and-file workers who wanted to prepare for the struggle, specifically urging them to subordinate themselves to the decisions of the TUC.

The Communist Party continued to condemn the “reactionary and unclear position of the [TUC] General Council” but did little about it.

Contributing to the weakness

The Comintern leaders not only ignored the problems of the British communists, they made the situation worse.

No one, including the CPGB, was seriously holding the ‘left’ trade union leaders to account for the failure to prepare the struggle. Partly this was because of the revolutionary authority afforded to these ‘left’ leaders by the Anglo-Russian Committee.

The illusions sowed by the Comintern in these ‘lefts’ meant that the NMM and the CPGB failed to make preparations for the showdown.

Instead of using the Anglo-Russian committee to push the trade union leaders to the left, it was the reformists who pushed the Comintern to the right. In December 1925, the TUC persuaded the Comintern to soften its criticism of the international organisation of reformist trade unions, the Amsterdam International.

At the 14th Congress of the CPSU in December 1925, a fierce debate took place over whether or not the Russian trade unions should join the Amsterdam International unconditionally. Tomsky said that communists should be prepared to go “to hell or to the Pope” to further the cause of trade union unity. He had the backing of Stalin and Bukharin.

The message being broadcast by the Comintern was that nothing was more important than trade union unity, which in Britain meant maintaining the Anglo-Russian Committee at all costs. What should have been an auxiliary tool in the struggle to build communist influence in the trade unions had become the primary aim of communist policy.

Precisely at the time when the reformist trade union leaders were being exposed by events, the Comintern clung more tightly to them.

Trotsky railed against this policy. In March 1926, he called for a “systematic unmasking of the muddle-heads of the left” in the trade unions. Without it, he warned, disaster loomed.

What was clear to Trotsky in March 1926 became clear to the British Communists only in hindsight. George Hardy, secretary of the NMM at the time, wrote in his memoirs:

“Although we knew of what treachery the right wing leaders were capable, we did not clearly understand the part played by the so-called left in the union leadership. In the main they turned out to be windbags and capitulated to the right wing.”

The General Strike

In the spring of 1926, the industrial ceasefire that had been in place since June 1925 was broken by the government proposing new attacks on the miners. In response, the TUC was forced to call a general strike on 4 May. This paralysed the country.

The trade union leaders, who had made no preparations for such a strike, found themselves thrust to the head of a powerful movement against the bosses and the government. The general strike had brought into being a revolutionary situation, but revolution was the furthest thing from the minds of these reformist trade union leaders.

As the strike began, Trotsky once again issued a warning about the ‘left’ trade union leaders. In the preface to the second German edition of Where is Britain Going?, published during the strike, he wrote:

“An English proverb says that one must not change horses while crossing a stream. This practical wisdom is true, however, only within certain limits. It has never yet been possible to cross a revolutionary stream on the horse of reformism, and a class which enters battle under opportunist leaders is compelled to change them under the enemy’s fire.”

But the CPGB had no perspective whatsoever of trying to change the leaders of the working class, despite the revolutionary potential of the strike and the weakness of the trade union tops. In fact, the party sowed even deeper illusions in these reformist leaders. Arthur Horner, the party’s national industrial organiser during the strike, recalled:

“During those nine days the working class took power into their own hands. I remember during the first days of the general strike addressing a demonstration of 60,000 at Llanelly and asking ‘Where is Baldwin now? Where is Churchill now? What matters now is what the TUC says. Our government is the TUC.’”

Betrayal by the ‘lefts’

The real role of the so-called ‘lefts’ on the TUC General Council soon became clear.

Workers in the USSR raised £1.25 million for the workers on strike in Britain, but this was rejected by the trade union leaders. Hicks, a member of the Anglo-Russian Committee, introduced the motion to the TUC rejecting the money and denounced “this damned Russian gold”.

This was to spit in the face of the Russian workers who were acting in solidarity with their English brothers and sisters.

On 8 May, the TUC announced that: “The Council has informed the Russian Trade Unions, in a courteous communication, that they are unable to accept the offer and the cheque has been returned.”

This was just a small foretaste of the betrayal that was to come. On 12 May, the TUC called off the general strike, having extracted no concessions whatsoever from the government or the bosses. This was despite, and even because of, the strengthening of the strike every day it continued.

The reformist trade union leaders were more afraid of the revolutionary potential of the mass movement they were forced to lead, than they were of the capitalist class and the Tory government.

Naturally the right-wing trade union leaders consciously planned this capitulation. But there was barely a squeak of protest from the left. In fact, it was a left-winger, Purcell, who was the head of the strike committee and announced the end of the general strike.

Communists in disarray

After months of fawning over the ‘left’ trade union leaders on the Anglo-Russian Committee, the CPGB was taken completely by surprise at the capitulation of the TUC ‘lefts’.

Tomsky, as head of the Anglo-Russian Committee, failed to grasp what had happened. He even painted the catastrophic capitulation as a victory!

He had instructed the British Communist Party to proclaim the strike as proof of “the failure of the Conservatives’ ideas and the partial moral victory of the proletariat [which will contribute] toward the ultimate success of the proletarian struggle.”

But the betrayal could not be whitewashed. The day after the strike, the CPGB published a statement which said the ending of the strike was “the greatest crime that has ever been permitted, not only against the miners, but against the working class of Great Britain and the whole world.”

On 15 May, two days after the end of the strike, the British communist leader R P Dutt wrote that the strike “was the first stage of the revolutionary struggle of the masses for power”. This was a clear rejection of the party’s previous analysis of the strike as purely a wage dispute.

He also argued that the betrayal of the TUC leaders was the product of nine months of right-wing sabotage and left-wing acquiescence. Telegrams were now sent out by the party office to all members attacking the left-wingers on the TUC.

This analysis from the CPGB was correct, although it came 12 months too late. The Comintern, on the other hand, couldn’t face up to reality.

On 26 May, a Politburo meeting was convened in Russia, at which Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev argued against Bukharin, Molotov, and Tomsky over the events in Britain. In the end, the theses of the latter were accepted. These put forward the contradictory position of criticising the “traitors” of the British trade union leadership while arguing that it was “a necessity” to preserve unity with them through the Anglo-Russian Committee.

The failure to grasp the reality of the craven betrayal by the TUC ‘lefts’, with whom the Soviet trade unions were allied in the Anglo-Russian Committee, was best demonstrated by Stalin. He argued that Tomsky had simply demonstrated “some carelessness, some gullibility” over his assessment of the strike, but that “we must still recognise that his mistake was minimal, insignificant”.

The Comintern’s stubborn refusal to confront reality head-on, or admit its past mistakes, meant that when the Central Committee of the CPGB met at the end of May it significantly toned down its criticisms of the ‘left’ trade union leaders in order to continue working with them.

On 4 June 1926, the party published a statement titled ‘Why the strike failed’ which said: “This strike was broken not by the power of the capitalist class, but by the failure of the right wing leadership.” There was no mention of the role of the lefts.

On 13 June, the Sunday Worker allowed TUC ‘left-winger’ George Hicks to write an article saying that the strike had been “a great victory” which had shattered the “moral prestige” of the ruling class.

The CPGB Executive Committee statement to the membership, dated 4 June, said:

“There will be a reaction within our Party against working with left-wing leaders. We must fight down this natural feeling and get better contact with these leaders and more mass pressure on them.”

Even after the abject betrayal of the so-called ‘lefts’ during the general strike, the leaders of the Comintern and the CPGB continued to chase after them, instead of breaking with them openly.

But the Russian leaders pursued a contradictory line. Some weeks later a manifesto was issued in Moscow blaming the failure of the strike on the “capitulation” of the TUC lefts and the “treacherous tactics” of the right.

The CPGB couldn’t keep up with the zigzags. It delayed publication of the translated manifesto for weeks, and then buried it in the 9 July issue of the Weekly Worker, for fear of damaging the Anglo-Russian Committee.

The Comintern’s insistence upon maintaining the Anglo-Russian Committee softened the tone of the NMM towards the TUC after the strike, which bewildered and disorientated those who felt betrayed.

Reformists turn on the communists

While the communists softened their criticisms, the TUC nevertheless instructed local trades councils not to allow the NMM to affiliate. There was opposition to this in Glasgow, Sheffield and Manchester, the largest trades councils in the country, but the CPGB advised them to submit without resistance, so as not to upset the Anglo-Russian Committee.

J. T. Murphy, the communist leader, recalled in 1934 that: “The workers could not understand this new alliance of the Communists and the [TUC] General Council and their resistance was killed.”

The TUC Congress in September 1926 invited Tomsky as a fraternal delegate, but the Home Office refused to grant him a visa, to which the TUC leaders did not object.

Despite all of this, in October 1926 at the 15th Congress of the CPSU, Tomsky and Bukharin drafted theses which argued that the Anglo-Russian Committee must be maintained “at any cost” even though it meant allying the Soviet trade unions with “traitors”.

In March 1927, the Anglo-Russian Committee met in Berlin. The British trade unionists demanded a new paragraph in the Committee’s constitution prohibiting criticism of their conduct, which shamefully the Russians accepted. Unity with the “traitors” was more important to the Comintern than speaking the truth to the working class.

On 12 May 1927, the Arcos raid led to the collapse of diplomatic relations between Britain and the USSR. The Soviet trade union leaders asked for a meeting of the Anglo-Russian Committee but were refused. The Committee had collapsed.

The Soviet trade unions had allowed themselves to be used as left cover by the reformists just long enough to betray the general strike, before being discarded like a dirty rag.

Learning the lessons

A few days later Trotsky drew the lessons:

“The Opposition foretold in its writings that the maintenance of the Anglo-Russian Committee would steadily strengthen the position of the [TUC] General Council, and that the latter would inevitably be converted from defendant into prosecutor…Our real friends, the revolutionary workers, can only be deceived and weakened by the policy of illusions and hypocrisy.”

On 1 August 1927, at the Central Committee of the CPSU, Trotsky addressed Stalin and his allies on their reliance on the TUC ‘Lefts’ instead of the CPGB and the NMM: “You rejected a small but sturdier prop for a bigger and utterly rotten one.”

He compared the policy to the one pursued in China: “Your present policy is a policy of rotten props on an international scale…each of these props broke at the moment when it was most sorely needed.”

Trotsky was right. The disastrous policy of the Comintern was the product of opportunism and the search for a shortcut. It snubbed the patient work of winning trade unionists to communist ideas, instead pursuing diplomatic manoeuvres with the trade union bureaucracy.

The Anglo-Russian Committee should have been a temporary and auxiliary device, but it was transformed into the pivot of international communist policy in Britain. It ended in disaster. It was a short-cut over a cliff.

The membership of the CPGB briefly surged as high as 12,000 in the months after the general strike, only to fall back to 7,000 by the time the Anglo-Russian Committee was dissolved; and then to 2,500 in 1930, with the adoption of the “Third Period”.

The Party failed to draw the conclusions from the Anglo-Russian Committee and the general strike, and so haemorrhaged members and influence among the organised layers of the working class.

To this very day, the Communist Party of Britain (CPB), the remnants of the old CPGB, has still not learned the lessons from this ruinous Stalinist policy. In 2020, the CPB wrote of the 1926 general strike:

“Between them the TUC right-wing and [the Tories] had managed to halt the highly dangerous process of working-class mobilisation…yet it was at great ideological cost to both the government and to the right-wingers…the government had at least temporarily lost the ideological battle.”

The leaders of the CPB continue to describe a defeat in terms of a ‘victory’. And, above all, nowhere addresses the treacherous role of the ‘left’ trade union leaders, the misadventure of the Anglo-Russian Committee, or the mistakes of the CPGB and Comintern leaders. In other words, they are wedded to their Stalinist past and its mistakes.

While Stalinists sweep their mistakes under the rug, genuine Marxists must learn the lessons from this experience.

The episode of the Anglo-Russian Committee is rich in instruction for those trying to connect radical ideas to the struggle of trade unionists today – ideas which are more relevant now than ever before.