“I think the UK is behaving a bit like an emerging market turning itself into a submerging market,” said Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, this week.

Summers was commenting on Tory chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget, which has caused a collapse of the pound on a worse scale than that seen in the early 1990s, after 9/11, or as a result of the 2008 financial crisis, Brexit, or COVID.

A collapsing currency is a sign that the international capitalist class view the UK economy as weak and unstable, and its Tory helmsmen as unreliable and reckless.

At a time when the whole world economy is weak and unstable, the UK economy is deemed an exceptionally bad case.

Even the IMF has stuck its oar in, criticising the Tory government’s economic plans, and stating that Britain is now being “closely monitored”. As the BBC commented, this “is the sort of warning the IMF more typically makes to emerging economies.”

Symptoms of sickness

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng have no doubt made a bad situation worse, pouring petrol on the flames with their Thatcherite tax cuts and handouts to the rich.

Nevertheless, they are not entirely to blame. The sharp fall in the pound is just the latest in a long list of symptoms indicating the sickness and decline of British capitalism.

For example, earlier this month, India replaced Britain as the fifth largest economy in the world.

In 2020, meanwhile, UK GDP contracted by 9.8%, more than any other G7 nation.

And the pandemic wasn’t the first time the British economy fared badly in a crisis. The collapse of 2008 caused a 7.1% decline in GDP, the largest fall of any of the major capitalist powers.

The IMF also predicts that the UK economy will grow more slowly in 2023 than any other advanced economy, at a rate of just 1.2%, while inflation will be higher and last longer.

Elsewhere, a recent report from the Resolution Foundation revealed that the 15 years between 2004 and 2019 were the weakest period for GDP growth per person in Britain since the years between 1919 and 1934.

Utopian fantasies

In this context, incoming prime minister Liz Truss and her zealous chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng have some bright ideas to reverse the fortunes of British capitalism.

To get the ball rolling, Kwarteng set a growth target for the British economy of 2.5%. After the announcement, one economist told the Financial Times that setting a growth target “achieves precisely nothing”.

This target does seem particularly utopian given that annual growth rates in Britain have halved since the 1960s, from around 3.5% to under 2%. This has become especially stark over the last 14 years, during which economic productivity has flatlined.

Kwarteng’s next step, after setting this fantastical growth target, was to announce last Friday’s mini-Budget. Far from reassuring investors, this provoked turmoil on the markets, resulting in the aforementioned drop in pound sterling.

The country’s devalued currency, in turn, will push up the cost of imports, fuelling inflation. And it will prompt further interest rate rises from the Bank of England, bankrupting UK businesses and families.

Exactly how this fits into the agenda for growth is a mystery.

Second-rate economy

Kwarteng and Truss are not the first politicians to suggest that economic growth might be a good thing. The problem is that the crisis of British capitalism has been a century in the making, and is inescapable for the British capitalist class and its representatives.

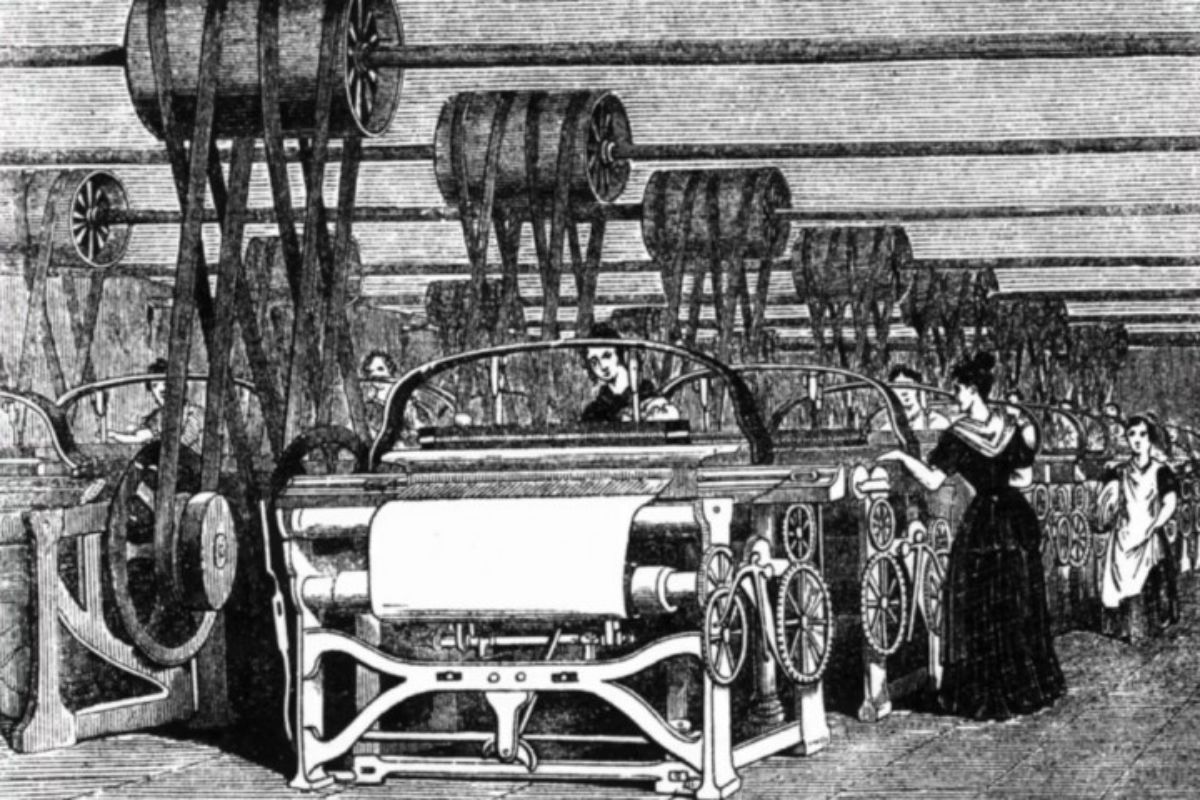

Two hundred years ago, Britain was the world’s foremost imperialist power and was a manufacturing powerhouse. It was the workshop of the world, with an empire encompassing one fifth of the world’s population, upon which it was said the sun would never set.

In 1826, one political commentator painted a picture of British capitalism in the following terms:

“The age which now discloses itself to our view promises to be the age of industry… The prospects which are now opening to England almost exceed the boundaries of thought; and can be measured by no standard found in history…The manufacturing industry of England maybe fairly computed as four times greater than that of all the other continents taken collectively, and sixteen such continents as Europe could not manufacture so much cotton as England does…”

Since then, a long and inglorious decline has turned Britain from a global superpower into a second-rate economy.

British capitalism, then, is clearly facing a special crisis. How did this happen to the former workshop of the world? And what does it mean for where Britain is going?

Industry and imperialism

Revolutionaries in Britain should study Trotsky’s text Where is Britain Going?, written in 1925.

In this, Trotsky explains that the industrial revolution turned the British economy into a huge importer of raw materials and exporter of manufactured commodities, giving it a dominant role in the world economy.

By 1900, Britain was responsible for 23% of global imports. And by 1922, its total exports reached 15% of the global total, rising to 29% when considering only manufactured exports.

As a result, between 1790 and 1890, real GDP per capita in Britain more than doubled, to a level over 33% higher than the USA and 70% higher than France or Germany.

It was this manufacturing and industrial base that placed Britain in the front rank of capitalist nations, making it the most powerful imperialist power.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, new states began to challenge Britain’s industrial dominance, especially Germany. This led to the First World War – a conflict between all the major imperialist powers to redivide the world market.

The huge economic power of the USA came to the fore during the war, pushing British capitalism into a secondary position. Britain’s national debt grew from £650 million in 1914, to £7.4 billion in 1919, with the US being the main creditor. By the mid-1920s, the US had gold reserves worth around six times more than those of Britain, reflecting its now dominant position in the world economy.

The British capitalists were faced with a difficult decision. If their industries were to remain competitive on the world market, then radical changes were needed. But this would provoke unrest among the working class, and instability in the colonies.

Relative decline

The Second World War postponed the decision. The postwar economic boom masked the relative decline of British capitalism.

From 1948-74, there was an important expansion of infrastructure in health, housing, roads, railways, schools, and universities.

But British capitalism continued its relative decline. By 1970, most European countries had more telephones, fridges, TVs, cars, and washing machines proportional to the population than Britain. By 1985, over 80% of young people in the USA, West Germany, and Japan were in education up to the age of 18. In Britain, this figure was less than 33%.

Academic Tony Judt described the postwar period as follows: “British factory managers preferred to operate in a cycle of under-investment, limited research and development, low wages and a shrinking pool of clients, rather than risk a fresh start with new products in new markets.”

Without the economic muscle to hold the Empire together, independence from Britain was demanded and conceded in one colony after another.

Once these former colonies were free to make their own trade agreements, the weak and uncompetitive British capitalists, who previously held a monopoly in these countries, found themselves turfed out of huge chunks of the world market.

Thus British exports as a percentage of world trade fell from almost 12% in 1948 to around 4% in 1974. Britain’s trade deficit was £200 million in 1948, but reached £4.1 billion by 1974.

Return of the crisis

So long as the world economy was growing, none of this mattered very much to the British capitalists. They were getting a smaller slice, but of a much larger cake.

But the underlying weakness of British capitalism was brought to the surface by the world economic crisis of 1974. The crisis which Trotsky had analysed in the 1920s now returned with a vengeance.

The British capitalists faced the same problem they had avoided in the 1930s: how to restore the rapidly declining fortunes of British capitalism in the face of powerful competition on the world market.

Long-term planning and investment in manufacturing had been central to building up British capitalism in the 19th century. The surplus extracted from the unpaid labour of the working class was ploughed back into industry. This was the basis of enormous growth rates.

But now the British ruling class shunned investment in production in favour of the service and financial industries. They also made cuts to workers’ wages and conditions, in order to maintain their profits.

This made sense for the individual capitalist. As an individual, Mr Moneybags is not interested in the health of the capitalist economy as a whole, but only in his own profits.

And profits can often be made faster through investment in the stock market, speculation, and the financial services industry, without the hassle and uncertainty of producing and selling actual commodities in a glutted world market; in other words, by making money out of money.

But what makes sense for an individual capitalist undermines the system as a whole. Low investment in real production – replacing worn-out machinery; skilling the working class; and developing new technology – cuts away at the productive base of the economy.

Bourgeois Luddism

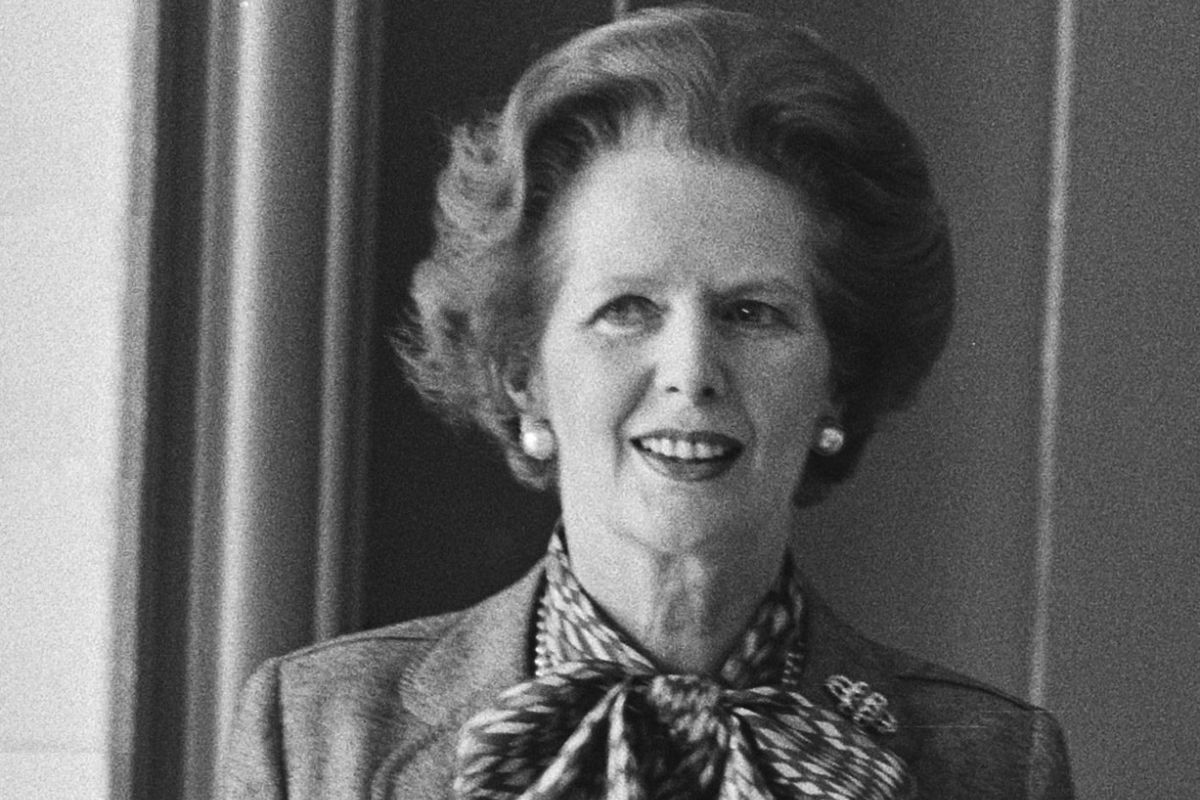

In the 1970s, the gradual migration away from investment and towards speculation became a stampede. The speculative British capitalists found their champion in Margaret Thatcher. With Thatcher as prime minister, 25% of Britain’s manufacturing base was destroyed.

A ‘Big Bang’ policy – involving a deregulation of the banks, finance houses, and investment firms – was aggressively pursued, tilting the British economy sharply towards a parasitic rentier economy, based on financial and legal services.

The impact of these policies was a kind of 20th century Luddism. Industry after industry went to the wall, in a frenzy of downsizing, asset-stripping, and takeovers.

Manufacturing industry dropped from 28.4% of GDP in 1971 to 23.1% in 1989. Those employed in manufacturing fell from 8.4 million in 1969 to 5.1 million in 1990.

Britain achieved balanced budgets by selling off nationalised industries to generate one-off windfalls. This is characteristic of the short-termism and myopia of the British capitalist class.

Quick profits were prioritised over investment in technology and skills. Figures from the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) show that from 1980 to 1990, investment per employee in the UK was £1,980; however, in Italy it was £5,360, in France £3,300, and in Germany £2,850.

By 1992, Britain was producing less than one third of the cars that France produces, fewer ships than Denmark, and less steel than Italy.

Finance capital demanded instant profits. And markets were increasingly driven by immediate gains for speculators. Steel and ships were dropped in favour of stocks and shares. Any firm not declaring higher dividends was threatened with takeover and dismemberment via asset-stripping.

As a result, investment in manufacturing rose by just 2% per year during the 1980s, but profits rose by 6% and dividends to shareholders 12%. In the 10-year period up to 1997, dividend growth outstripped investment growth by a ratio of 3:1.

This period saw a dramatic hollowing out of British capitalism. The economy was taken over by coupon clippers, whose primary role is to act as middlemen and gamblers, gouging their rents, interest, and commissions out of the value created in the production of real commodities.

The bloodsucking banking sector increased from 9.3% of GDP in 1971 to 18.7% in 1989. Industry increasingly came to be regarded as the old-fashioned means of doing business, as opposed to the modern approach of derivatives and financial wizardry.

The British capitalists shipped their industrial activities abroad, and imported the goods required.

Up until 1982, Britain’s balance of trade for finished and semi-manufactured goods was positive. But from 1983 onwards there has been a trade deficit in these commodities, which has steadily widened.

Britain’s imperialist power had been rooted in its manufacturing base. But this was whittled away by the capitalists, in favour of financial services and speculation: rentier, parasitic elements in the economy, dependent on real production taking place elsewhere.

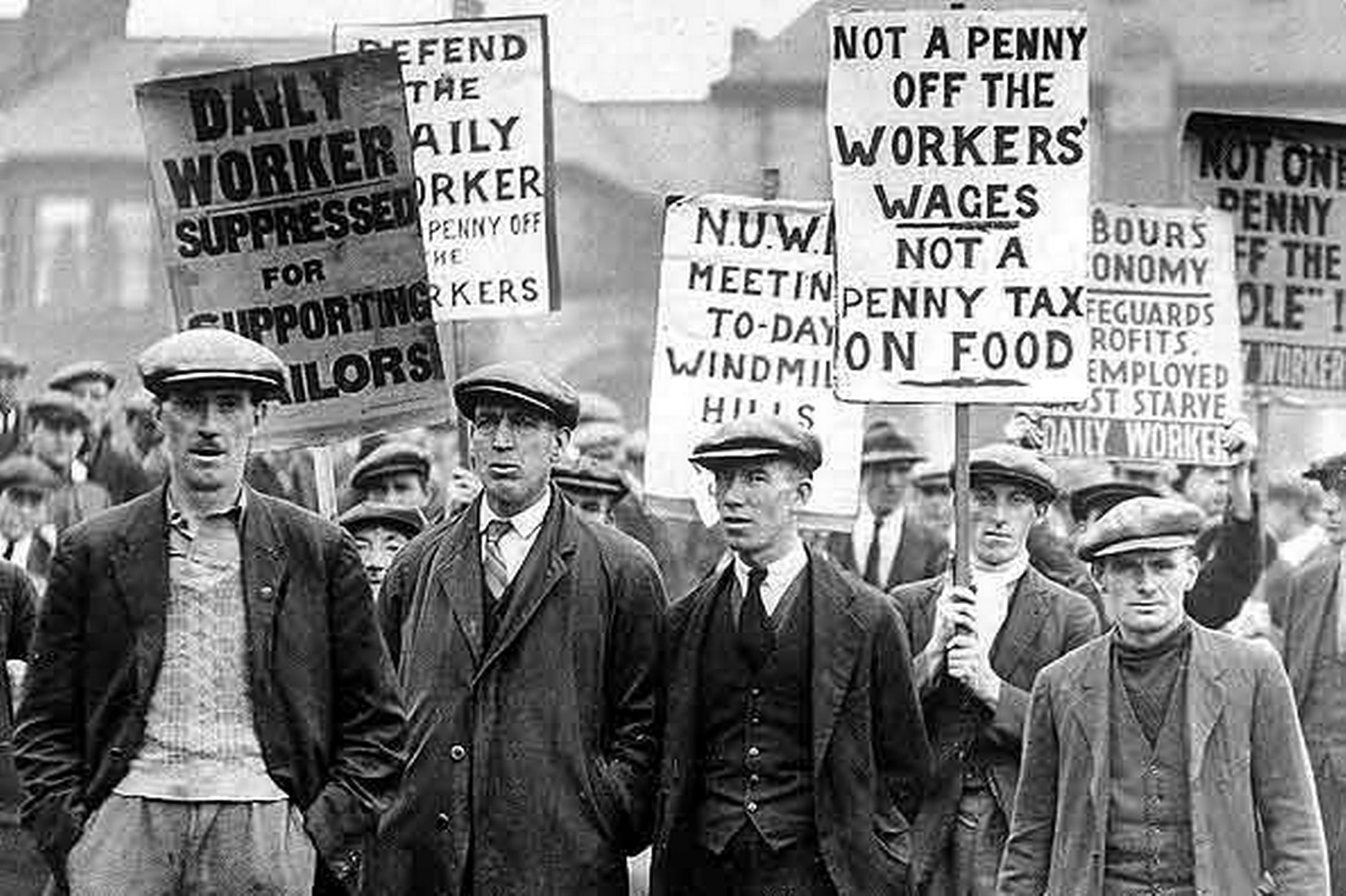

Making workers pay

The Luddism of the bourgeoisie was combined with an all-out attack on workers’ wages and conditions. With this, the British capitalists hoped to restore their rate of profit, which had been falling for decades, and to drive down standards, making UK exports cheaper than their rivals.

The ruling class declared open war on the unions. They put their full weight behind Thatcher’s attempt to break the power of the trade unions.

In this, she was largely successful, following through with ferocious attacks on conditions and wages. Greater economic competitiveness was gained, not through investment, but through speed-ups, a lengthening of the working day, wage cuts, and a greater intensity of labour.

This employers’ offensive has continued for decades, and has seen the introduction of labour ‘flexibility’ across the board. Part-time working, casualised labour, and precarious short-term contracts are all hallmarks of the special crisis of British capitalism.

It should be noted that, despite the enormous pressure piled on workers over the last few decades, the British economy continues to fall behind its rivals. In the arena of the world market, a low-wage economy is no match for productive machinery.

Britain became a world power by exactly the opposite means: by investing and developing its manufacturing and industrial base. It is precisely British capitalism’s failure to invest in the means of production – in machinery and industry; in technology and technique – that continues to force it further behind its rivals.

Coming home to roost

The deregulation of financial services from the 1980s onwards resulted in an explosion in credit. A proliferation of loans, credit cards, and mortgages allowed workers to maintain their purchasing power and keep their heads above water, despite the bosses’ attacks on wages.

In other words, the capitalists were able to continue selling their commodities to workers, thus avoiding a crisis, whilst also increasing the exploitation of these very same workers in order to boost profits.

In 1987, UK household debt had reached 55% of GDP. By 2009, that figure had skyrocketed to £1.4 trillion: 105% of GDP.

The banks had granted hundreds of billions of pounds in loans to people who were unable to pay them back. This was the inevitable product of a short-term hunt for quick profits, with no regard for the consequences.

In 2008-09, the chickens came home to roost. A global financial crisis brought all the contradictions of capitalism to the surface.

The collapse in UK gross domestic product – of 7.1% – was on a par with the Great Depression. This was the biggest decline of any of the major capitalist powers.

As a consequence, the British government spent £137 billion on bailing out the banks. Government debt grew to be larger than all the debt in peacetime combined going back to the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688.

The 2008 collapse was worse in Britain because financial services, retail, and real estate had taken over as the base of the UK economy. Between 2005 and 2007, financial services and housing-related businesses made up 60% of the growth of the British economy. All of this depended on risky borrowing and lending, which dried up during the credit crunch.

The destruction of the UK’s manufacturing base over the previous 30 years meant that the economy was far more vulnerable to economic shocks of this kind.

Not only did the stock of capital goods in the manufacturing sector not grow in the period 2000-2007, it actually declined.

This situation was made even worse by the lack of investment in what little manufacturing remained in the UK. By 2009, almost half of all manufacturing investment in Britain was from foreign multinationals, rather than the British capitalist class themselves.

Unable to change course

The crash of 2008-09 revealed the weakness of British capitalism. But since then, it has become weaker still.

The 2008 crisis was one of global overproduction, where more was being produced than could be profitably absorbed by the world market.

Instead of allowing the unprofitable businesses to fail, the capitalists have artificially propped up the economy with bailouts and more cheap loans.

Thus the financialisation of the economy has continued even faster than in the 1980s. Whereas Thatcher implemented high interest rates, which restricted risky credit and investment, the capitalist class since 2009 has enforced record low interest rates (until recently).

This means cheap money has been looking for places to invest. Investment in production has been restricted by overproduction, monopolisation, and uncertain economic conditions. So this cheap credit has instead fuelled an unprecedented boom in speculation over the last decade, as well as mushrooming debt.

In 2007, global debt to GDP stood at 195%. Two years later it was at 215%. But by 2019, it had increased even further to 227%, despite the vicious austerity programmes implemented by governments around the world.

UK debt was 48% of GDP in 2008-09. But by 2019, this figure had increased to 83%. Following the pandemic, it now stands at 96%.

Meanwhile, British banks grew to become some of the biggest in the world. By 2016, their loans and investments were equal to more than five times annual UK GDP. That year, 41% of all global financial transactions went through London, which also had a 70% share of trade in global bonds and a 47% share of trade in derivatives.

At the same time, between 2007 and 2016 British manufacturing shrank by 7%.

British manufacturing today accounts for just 1.8% of global manufacturing output – lower than South Korea, Italy, and India, and only fractionally higher than Indonesia.

There has been a dramatic decline in investment in the British economy. In 2016, the UK ranked 116th out of 141 countries for capital investment as a percentage of GDP.

This has resulted in the stagnation and fall of the productivity of labour. During the 2010s, the European Union, Sweden, Ireland, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Denmark all overtook Britain in terms of productivity.

To maintain competitiveness in the face of this lack of investment and declining productivity, the British capitalists have spent the last decade driving down wages and conditions for workers.

The International Labour Organisation reports that hourly labour costs in Britain in 2017 were $30. This is lower than in Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, Germany, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, Italy, Finland, Iceland, and Ireland.

An economy based on parasitic service industries and low wages has not been able to compete and grow. In 2010, British GDP was 11% below its 1980-2007 trend. But by 2013 it was 16% below this trend.

British capitalism has become more dependent on imports, as its own productive base has been destroyed. In 1997, the trade deficit in manufactured goods was £7.5bn, but by 2018 it was £92bn. In 2020, Britain was ranked 126 out of 127 countries in a balance of trade comparison, making it one of the most import-dependent countries in the world.

This weakness is illustrated by the rapidly growing deficit in balance of payments. In 2007, Britain’s net income from trade and investment overseas was in a deficit of around 3% of GDP.

Today, that deficit is forecast to be around 8% of GDP. Since records began in 1772, this level of trade and investment deficit has only been reached three times, all of them during World War Two.

Plumbing new depths

Britain’s import-dependency is both a product of the special crisis of British capitalism and an accelerant. Trade makes up a third of Britain’s GDP. This means that the chaos now wracking global supply chains – thanks to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine – has hit Britain especially hard.

Similarly, the UK’s high level of imports, combined with the fall in the pound, has added to the inflationary pressures that are fuelling the cost-of-living crisis.

Brexit has compounded this disruption. Between 2017 and 2021, trade in goods and services increased in Japan (18%), Italy (15%), Spain (9%), Germany (8%), France (4%), but has declined in Britain by 6%.

Another impact of Brexit has been to cut investment in research and development even further. British researchers have lost £250 million of funding from the European Horizon programme, due to the dispute over the Northern Ireland Protocol.

Meanwhile, overall investment in research and development stood at just 1.74% of GDP in 2021, compared to 2.2% in France, 3.1% in the USA, and 3.2% in Germany.

These dismal statistics document the failure of the British capitalist class to invest in its economic base. The last two years have made it worse. UK business investment is currently 9.1% below pre-pandemic levels. And UK manufacturing sector insolvencies have risen by 63% since last year.

This lack of investment continues to impact productivity in Britain, which today is estimated to be 20% lower than in France and Germany, and 30% lower than in the USA.

For all these reasons, and more, the UK economy is predicted to fare the worst out of all the G20 nations (except Russia) in the coming period.

Tory gamblers

This long process of decline for British capitalism has found its reflection in the degeneration of its political representatives. Thatcher epitomised the short-termism of the new breed of capitalists, presiding over the de-industrialisation of Britain.

Since then, the UK economy has been taken over by wild speculators and frenzied finance capitalists. The bourgeois political representatives in the Tory Party have correspondingly become increasingly short-sighted.

In 2016, David Cameron gambled the long-term strategic interests of British capitalism for his own short-term political gain, by calling the EU referendum.

Cameron lost his gamble. And since then, the Tory Party has slid even further out of the control of the capitalist class.

Boris Johnson finished what Thatcher had started, delivering control of the party to frothing, swivel-eyed reactionaries, with little understanding of the interests of British capitalism as a whole.

Liz Truss is continuing where Johnson left off. Despite Truss’ offers of tax cuts for the rich and big business, the strategists of capital are worried that her economic plans will not serve their best interests. That wariness has caused the pound to sink to its lowest level against the dollar since 1985.

Undeterred, her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, has doubled-down on Thatcherite economic policies, promising a ‘Big Bang 2.0’ of even more deregulation for the financial services sector, all in pursuit of short-term profits at the expense of a long-term strategy.

Last Friday’s mini-Budget was a masterclass in short-termism. Tax cuts for the rich are designed to boost the headline growth figures in the immediate term. But these are to be funded by borrowing money, which will have to be paid back in the future – at an increasingly high rate of interest.

Investors are therefore increasingly worried that the UK government will be unable to pay its debts. Hence the recent rise in government bond yields, which pushes up the cost of public borrowing even further, and the collapsing confidence in the British economy on the market.

Truss and Kwarteng, in this respect, are only the latest in a long line of Tory gamblers; the perfect frontmen for the casino that is British capitalism.

And the British capitalists only have themselves to blame. Their short-term chase for profits has produced representatives incapable of defending their interests.

Red dawn

In the past, where necessary, the bourgeoisie has been able to lean on the leaders of the working class – who it has bribed and corrupted – to do its dirty work. The special crisis of British capitalism has undermined this strategy.

Whereas the spoils of Empire in the past allowed for the cultivation of an ‘aristocracy of labour’, today the British capitalists have nothing left to offer the workers’ leaders.

This makes them harder to control, which makes the class struggle less predictable, and leaves the ruling class with fewer options to deal with the developing crisis.

As the crisis of capitalism deepens, Britain is being hit particularly hard. In this new period of class struggle, British capitalism has never been weaker.

The British capitalists have hollowed out the economy, presided over the degeneration of their representatives, and weakened their hold over the labour movement.

It was once said that the sun would never set on the British Empire. But today, we are in the twilight of British capitalism.

The conscious intervention of the working class can bring about the red dawn of a Socialist Federation of the British Isles. This is what we’re fighting for.