“We are all Keynesians now!” So President Richard Nixon is alleged to have said in 1971, as his Republican government of the time intervened to rescue the American economy.

Unemployment and inflation were both on the rise, something that mainstream economic models said could not happen. The strength and stability of the dollar was being called into question. And the Bretton Woods system that had underpinned the postwar boom and US imperialist hegemony was on the verge of collapse.

In reality, the quotation is likely apocryphal. Nevertheless, it represents a revealing truth: that bourgeois politicians of all stripes and colours are – in the face of crisis – willing to utilise the full resources of the state to prop up capitalism.

Fast forward almost four decades and the validity of this statement is once again on display. 13 years on from the great crash of 2008, when governments across the world poured taxpayers’ money into the banks to avert a financial implosion, and history is repeating itself with the coronavirus crisis.

In total, over $16.5 trillion in state support has so far been thrown at the global economy over the course of the pandemic. And in the USA, President Biden is currently pushing for a further $4.5 trillion in spending – on top of the $1.9 trillion stimulus package already enacted in March this year, not to mention the trillions handed out by the Trump administration in the form of cheques to households and emergency funding to businesses.

The state stepping in to manage capitalism; governments borrowing and spending in order to save the system: this is the legacy that John Maynard Keynes will no doubt always be remembered for.

And it is a legacy that has been warmly embraced by the leaders of the labour movement today, who long ago abandoned the call for genuine socialism.

Instead of fighting to transform society, the reformist leaders now resign themselves only to futile – but supposedly ‘realistic’ – attempts to patch up capitalism. And, ironically, it is the theories of a lifelong and self-professed liberal bourgeois economist that these ladies and gentlemen turn to in their efforts to justify their acquiescence.

But as The Price of Peace – a recently released biography of Keynes – demonstrates, the Englishman and his proposals were not always so in vogue. Indeed, for most of Keynes’ life, he was ignored by the ruling class, who considered his ramblings to be “extreme and reckless utterances”.

As Keynes himself was forced to admit, writing in 1931 in the preface to his Essays on Persuasion, his ‘pragmatic’ advice and warnings to the elites were nothing more than “the croakings of a Cassandra who could never influence the course of events in time”.

Later, Keynes’ ideas became very fashionable amongst economists and politicians.

For socialists, however, far from offering a solution to the crises facing humanity, Keynesianism is a programme designed to bail out a bankrupt system. Workers and youth should turn their back on these ideas and fight instead for a break with capitalism – for socialist revolution.

Liberalism and Utopianism

John Maynard Keynes was a true product of his time and his conditions. Born in 1883 into an academic family, and educated at Eton and Cambridge (originally in mathematics), ‘Maynard’ was always most comfortable when rubbing shoulders with other members of the ivory-tower elite.

Whilst studying at King’s College, Cambridge, he became president of the university’s debating chamber and also its Liberal Club. And he was soon recognised by his peers, who invited him to join the secretive ‘Apostles’ society – an exclusive group of intellectuals, dominated at the time by the abstract and formalistic philosophies of G.E. Moore, and later by similar thinkers such as Bertrand Russell.

It was through the Apostles that Keynes formed the friendships that would later collectively be known as ‘The Bloomsbury Group’, whose other members included the novelist E.M. Forster and writer Virginia Woolf.

Although some of these bohemians and artists would be pushed left by events later in life, the overriding characteristic of the Group was one of “unsurpassable individualism”, as Keynes himself acknowledged in a speech entitled My Early Beliefs, delivered in 1938.

“Moreover,” Keynes proudly emphasised, “our philosophy…served to protect the whole lot of us from…Marxism.”

“[We] ourselves have remained – am I not right in saying all of us? – altogether immune from the virus, as safe in the citadel of our ultimate faith as the Pope of Rome in his.”

At the same time, Keynes confessed, “We were among the last of the Utopians…who believe in a continuing moral progress by virtue of which the human race already consists of reliable, rational, decent people, influenced by truth and objective standards…”

In this respect, JMK represented the twilight of liberalism, with its idealistic belief in ‘eternal truths’, ‘universal values’, and ‘rational individuals’ – a philosophy that ultimately reflected the material needs and interests of the bourgeoisie in its bygone heyday.

And it was a utopian idealism that would stick with Keynes for the rest of his life, as we shall see, leading him to constantly be rebuffed by a ruling class that thought not in terms of ‘rationality’ and ‘decency’, but in the cold, hard calculus of capitalist ‘realpolitik’.

Class interests

Keynes desperately wanted to return to the ‘Golden Age’ of the 19th century: a time when ‘civilised’ gentlemen such as himself had lived a peaceful existence – on the backs of the working class and the colonial masses, of course.

“What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was which came to an end in August 1914!” Keynes declared, looking back in the aftermath of ‘The Great War’ – conveniently overlooking the fact that it was precisely the contradictory developments of this period, during the growth of imperialism, that intensified the antagonisms that eventually burst forth with the onset of WWI.

Indeed, as biographer Zachary D. Carter notes, Keynes’ writings are “fused with a naive nostalgia for pre-war politics that sidesteps 19th century colonial outrages to meditate on his own leisure-class experience.”

Later in life, Carter explains, Keynes “had become disillusioned with the way his country managed its empire, but he had never stopped working toward the ideal of Great Britain that he had treasured as a young man: a strong nation leading the world to truth, liberty, and prosperity.”

This rose-tinted view of the British Empire and its imperialist history once again highlights the real class interests that Keynes and his fellow liberals truly sought – and still seek – to defend: those of imperialism and the capitalist class.

Keynes’ liberal concept of progress, meanwhile, was not measured by the living standards of ordinary people, but by the quantity and quality of bourgeois culture; by the position afforded to those – like himself – in the upper-echelons in society.

In reality, Keynes held the working class in contempt. For him, “the well-being of the masses is a convenience that raises cultural standards for elites,” Carter stresses, “while the masses themselves are a danger that must be defused.” (Our emphasis)

And, as if to leave any doubt, in a 1925 essay entitled Am I a Liberal?, the English economist categorically stated his disdain towards the rising Labour Party and the working class, in no uncertain terms:

“[Labour] is a class party, and the class is not my class. If I am going to pursue sectional interests at all, I shall pursue my own. When it comes to the class struggle as such, my local and personal patriotisms, like those of everyone else, except certain unpleasant zealous ones, are attached to my own surroundings. I can be influenced by what seems to me to be justice and good sense; but the class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie.” (Our emphasis)

These words, alone, should be enough to demonstrate that Keynes was no friend of the labour movement and the working class.

War and peace

After graduating from Cambridge, Keynes joined the civil service as a clerk in the India Office, before returning to his alma mater to pursue a career in academia.

When WWI broke out in 1914, Keynes was called back down to London to help the government prop up the gold standard in Britain, which was coming under pressure due to the financial turbulence that the war brought.

Keynes and the rest of the Bloomsbury set were all nominally pacifist types. And yet after saving the City of London, Keynes went on to spend the rest of the war years in H.M. Treasury, advising the government on how to fund its imperialistic military endeavours.

“It was an extraordinary tangle of convictions,” Carter writes in The Price of Peace. “Keynes raised money for the war effort even as he sought to deprive the British army of its soldiers. He was disgusted by the nationalist chauvinism of British politicians, but he was helping those same leaders win a war for imperial territory. Keynes was at war with himself.”

As a reward for this work, Keynes was promoted to a position that would later help propel him to global fame: the Treasury’s official representative to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where the infamous Treaty of Versailles was brokered.

Keynes observed the conference first-hand, with access to official discussions and documents. On this basis, he was able to produce a scathing critique of the Treaty and its key protagonists, entitled The Economic Consequences of the Peace. This was published later in the same year to much acclaim.

The book went on to become an international bestseller. In it, Keynes denounced the Allied leaders – in particular Clémenceau, the French Prime Minister – who he believed had cooked up an agreement designed to ruthlessly “weaken and destroy Germany in every possible way”, in the interests of French, British, and American imperialism.

“The future life of Europe was not their concern; its means of livelihood was not their anxiety,” Keynes wrote. “Their preoccupations, good and bad alike, related to frontiers and nationalities, to the balance of power, to imperial aggrandizements, to the future enfeeblement of a strong and dangerous enemy, to revenge, and to the shifting by the victors of their unbearable financial burdens on to the shoulders of the defeated.”

British politicians, meanwhile, were no less guilty than the French, Keynes believed. Liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George, for example, was under pressure from Conservatives back home to “squeeze her [Germany] until you can hear the pips squeak”.

Together, Keynes asserted, Lloyd George, Georges Clémenceau, and their American counterpart, President Woodrow Wilson, would bring about a “Carthaginian peace”, based upon the ruin of Germany and its people. The reparations demanded by the Allies, the English economist showed, were simply unpayable. This, Keynes prophetically predicted, would pave the way for further animosity and antagonism across Europe.

Keynes’ pessimism was soon borne out. Bankrupt and broken, the Weimar Republic resorted to printing money in order to meet their debts. Hyperinflation and dire impoverishment ensued.

This, in turn, paved the way for an upsurge of revolutionary struggle; and when this was defeated, for the rise of fascism and the re-emergence of German imperialist ambitions on an even higher level, under the banner of Nazism.

Fear of revolution

The Economic Consequences of the Peace has gone down in history for its withering criticisms of the European leaders, alongside its sharp attacks on the League of Nations for being “an unwieldy polyglot debating society…in favour of the status quo”.

But this was not the anti-establishment polemic that it has subsequently been painted as. Rather, Keynes’ book was the first of many naive and idealistic warnings offered by the liberal soothsayer over the course of his life, all designed as desperate pleas to the political elites, with the aim of averting potential disaster.

Importantly, it was not so much the decimation of German living standards that worried Keynes, but the fear of the potential revolutionary wave that this would provoke.

“As I write, the flames of Russian Bolshevism seem, for the moment at least, to have burnt themselves out,” Keynes stated. “But who can say how much is endurable, or in what direction men will seek at last to escape from their misfortunes?”

As Carter notes in his biography, Keynes liked to see himself as a man of enlightened progress. But his perspective on events was always profoundly influenced by the reactionary conservatism of Edmund Burke, whose writings he had been drawn towards as a student.

This, in turn, reflected his own privileged class position and background, which he never broke from. And these views came to bear on all the advice that Keynes proffered to the ruling class.

At the end of the day, Carter correctly states, “Keynes made his radical propositions [of The Economic Consequences of the Peace] in an effort to preserve what could be saved of the status quo, which he believed to be facing an existential threat.”

“Keynes had crafted an innovative philosophical cocktail,” Carter continues. “Like Burke, he feared revolution and social upheaval. Like Karl Marx, he envisioned a great crisis on the horizon for capitalism. And like Lenin, he believed that the imperialist world order had reached its final limit.”

“But alone among these thinkers, Keynes believed all that was needed to solve the crisis was a little goodwill and cooperation. The calamity he foresaw in 1919 was not something inevitable, hardwired into the fundamental logic of economics, capitalism, or humanity. It was merely a political failure, one that could be overcome with the right leadership.

“Whereas Marx had called for revolution against a broken, irrational capitalist order, Keynes was content to denounce the leaders at Versailles and called for treaty revisions. As with Burke, it was revolution itself that Keynes hoped to avert.”

But as became the pattern in subsequent years, Keynes’ appeals fell on deaf ears.

What this liberal thinker could never understand or accept is that the capitalist class and their political representatives do not act on the basis of what is ‘rational’ or ‘right’. They are not persuaded by the power of ideas, but by the blind pursuit of profit and naked imperialist interest. And no amount of eloquent prose or articulate arguments will change that.

In short, society is not made by ‘Great Men’ with ‘Great Ideas’, but by a struggle of living forces; a struggle between antagonistic classes, fighting for their own material interests.

This is the materialist view of history, as explained by Marx and Engels in the opening lines of the Communist Manifesto: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

But it is a view that Keynes – epitomising the idealistic liberalism of his own class – could never reconcile himself with. And so he became destined to repeatedly play the part of the impotent oracle; a ‘croaking Cassandra’, forever snubbed by the very elites whose system he was trying to save.

Decay and decline

Keynes’ biting remarks in The Economic Consequences of the Peace did not endear him to the British establishment in the years that followed. Ostracised from Whitehall, Keynes returned to the bubble of academia. At the same time, he moonlighted as a journalist and a stock market gambler in order to pay his way in the high society circles to which he had become accustomed.

It was from this comfortable position that Keynes built up his reputation as an influential intellectual and political commentator. And in the wake of the war, there were no shortage of crises from him to comment on.

Britain had entered the war as the centre of the capitalist world, with a mighty empire spanning the globe. But she had emerged as a second-rate power, unable to compete with the rising might of American industry and finance.

Indeed, the results of the Versailles negotiations were a bit of a reality check for the British and French imperialists. Whilst claiming reparations from Germany, London and Paris found that they, in turn, owed vast sums to Washington and Wall Street. The centre of gravity had firmly shifted across the Atlantic.

But the British ruling class could not accept their newly diminished role on the world stage. Puffed up by their own hubristic sense of self-importance and imperial grandeur, the establishment vastly overestimated the strength of British capitalism, which was in steep decline.

Leon Trotsky outlined this process in his book Where is Britain Going?, in which he vividly described British imperialism’s fall from grace:

“During the war the gigantic economic domination of the United States had demonstrated itself wholly and completely. The United States’ emergence from overseas provincialism at once shifted Britain into a secondary position…

“Great Britain’s productive forces, and most of all her living productive forces, the proletariat, no longer correspond to her place in the world market. Hence the chronic unemployment.”

This economic decay, meanwhile, reflected itself politically as a crisis of liberalism – a bourgeois creed built upon a strength and stability that was long-gone. As Trotsky astutely noted:

“The break-up of the Liberal Party crowns a century of development of capitalist economy and bourgeois society. The loss of world domination has brought whole branches of British industry to a dead end and has struck a lethal blow at self-sufficient medium-sized industrial and commercial capital – the basis of Liberalism. Free trade has reached an impasse.

“In the past the internal stability of the capitalist regime was in large measure assured by a division of labour and responsibility between Conservatism and Liberalism. The break-up of Liberalism exposes all the other contradictions in the world position of bourgeois Britain at the same time as it reveals the internal crisis of the regime.”

This economic and political volatility led to a string of elections between 1922 and 1924. A fading Liberal Party was rapidly losing ground to a rising Labour Party, indicating the growing organisation and radicalisation of the working class.

In the turmoil, the Conservatives were able to squeeze through, with Stanley Baldwin forming a majority government out of the 1924 general election. But with British capitalism crumbling, this would prove to be a crisis Tory government from beginning to end.

Churchill and gold

The key question facing the Conservative government was what to do about Britain’s relationship with the gold standard. For the establishment, this was not a mere economic question, but one of pride and prestige.

Britain had effectively spread and managed the gold standard in the 19th century, given the dominance of the Empire, which provided a relatively firm foundation for world trade (in the interests of the British industrialists and financiers, of course). But with the outbreak of WWI, the government had suspended the gold standard, which was collapsing in the face of financial turmoil.

At the same time, the war had exposed the weaknesses of British capitalism, which was no longer competitive compared to her American and German rivals. And yet there had been no realignment in terms of the value of the pound to reflect this new reality.

The arrogant ruling class, determined to restore the country to its former glories, insisted that Britain should return to the gold standard at the pre-war rate of convertibility. For the establishment, Carter explains, “the gold standard carried a profound social meaning”, expressing the “older principle of Enlightenment liberalism”.

“Gold represented a normal state of affairs in which the world was gliding inexorably to peace, prosperity, and progress. And since the pre-war system had collapsed at its zenith, a return to the gold standard was viewed as an opportunity to revive a lost glory, to prove that there were some things even the Great War could not destroy.

“For prominent bankers, Keynes noted, restoring the gold value of the pound was a question of ‘national prestige’ – of ensuring a ‘more glorious’ Great Britain.”

Alongside this nationalistic pomposity, pressure from the City of London also played a part. After all, any devaluation of the pound would mean that existing debts – owed to the bankers – would be wiped out.

“More sophisticated City grandees,” Carter continues, “believed that if London hoped to recover the financial power it had ceded to Wall Street during the war, it would have to prove that investing in Great Britain was a better bet than investing in the United States.”

“That meant demonstrating to the global financial markets that the British government would not allow anything to devalue their investments in British money or British debt – not even war.”

And so, in 1925, the Tories brought in the British Gold Standard Act, pegging pound sterling to gold at the old pre-war rate.

Keynes was adamantly opposed to the move, and had voiced his concerns in advance on numerous occasions. In a series of articles and speeches, he explained that British capitalism could only continue trading competitively at this vastly overvalued rate by implementing a policy of ‘internal devaluation’ – that is, by attacking workers’ wages and conditions.

“We can seek at all costs to restore the pre-war equilibrium of large exports and large foreign investments,” Keynes stated, “But those who think that a return to the gold standard means a return to these conditions are fools and blind…The return to gold has rendered this impossible without an all-round attack on wages.”

The Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time was none other than Winston Churchill. And in a reference to his own earlier work, Keynes aimed fire at the Tory Chancellor in an essay entitled The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill.

“The policy can only attain its end by intensifying unemployment without limit,” Keynes wrote in his latest polemic, “until the workers are ready to accept the necessary reduction of money wages under the pressure of hard facts.”

As ever, however, Keynes was blind to the callous economic interests lying behind Churchill’s decision. “Why did he [Churchill] do such a silly thing?”, the Cambridge academic rhetorically asked; “because…he was deafened by the clamorous voices of conventional finance; and, most of all, because he was gravely misled by his experts.”

Keynes consistently believed that he could appeal to ‘reason’; that he could make these ruthless representatives of the capitalist class see the error of their ways. But his efforts were to no avail.

“On ground of social justice, no case can be made out for reducing the wages of the miners. They are victims of the economic juggernaut. They represent in the flesh the ‘fundamental adjustments’ engineered by the Treasury and the Bank of England to satisfy the impatience of the City fathers…

“They (and others to follow) are the ‘moderate sacrifice’ still necessary to ensure the stability of the gold standard. The plight of the coal miners is the first, but not – unless we are very lucky – the last, of the Economic Consequence of Mr. Churchill.”

Foresight and astonishment

The impotence of Keynes’ utopian liberalism is revealed here for all to see. And all the more clearly so when juxtaposed with the writings of Leon Trotsky from the same time.

In Where is Britain Going?, Trotsky was writing for the working class, preparing and arming the labour movement with the necessary perspectives and ideas to fight the bosses. His liberal English counterpart, meanwhile, was attempting to persuade Tory politicians to respect “social justice” – in effect, attempting to convince carnivorous tigers to become vegans.

Once again, Keynes was prophesying doom. But as with his critiques of the Versailles Treaty, Keynes’ cries about the gold standard were not motivated by concern for workers, but by his innate liberal fear of class struggle and revolution.

“The working classes cannot be expected to understand, better than Cabinet Ministers, what is happening,” Keynes implored in his open letter to Churchill. “Those who are attacked first are faced with a depression of their standard of life…Therefore they are bound to resist so long as they can; and it must be war, until those who are economically weakest are beaten to the ground.” (Our emphasis)

Both Trotsky and Keynes, then, had the foresight to see the class struggle that was brewing in Britain. Indeed, only a year on from these writings above, in 1926, the country was rocked by the General Strike.

But unlike Trotsky, who was armed with Marxist theory, the naive Keynes was left astonished by what he perceived to be an incomprehensible stubbornness and stupidity of the ruling class. And so he was consigned to huff and puff with desolate rage.

“Keynes believed the strike to be a social disaster,” Carter explains in his biography, “caused not by some historically inevitable conflict between the working class and the capitalist regime but by straightforward intellectual error.”

“Churchill and the Bank of England had simply been wrong and refused to listen to reason. Keynes had offered what was becoming his classic policy formulation: pursuing a conservative aim of avoiding a class revolt by implementing an unorthodox, left-wing reform—breaking with the gold standard.

“And Churchill had rejected him, not because he was corrupted by vested interests or class solidarity with the wealthy but because he just didn’t think straight. He could have been convinced otherwise.

“There was more than a touch of naivete in Keynes’ faith in the power of ideas and persuasion, but he rested his hopes for intellectual process on reasonable men in government, rather than the executive suite.”

Ironically, as with his ‘croakings’ over war reparations, Keynes was largely vindicated by history. Churchill later admitted that it was a mistake to tie the pound to gold at such elevated levels, given the severe austerity and deflationary effects that this entailed. And the economist’s own alternative proposal for a ‘managed currency’ is effectively what Britain, the USA, and other monetarily ‘sovereign’ countries now have in place.

The fact is, however, that Keynes’ suggestions were rejected by the ruling class – a pattern that would become all too familiar to him over his lifetime. And so it is with all the hysterical liberal commentators today, who fruitlessly decry the ‘madness’ of ‘populists’, calling for the ‘sensible people’ to take charge.

Their pathetic wailings, in the words of the Bard, are “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”.

The General Theory

Whilst British capitalism underwent a decline throughout the decade, America was experiencing the dizzy thrills of the ‘Roaring Twenties’. The merry-making would all turn to tears, however, with the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which ushered in the Great Depression – the deepest crisis in the history of capitalism.

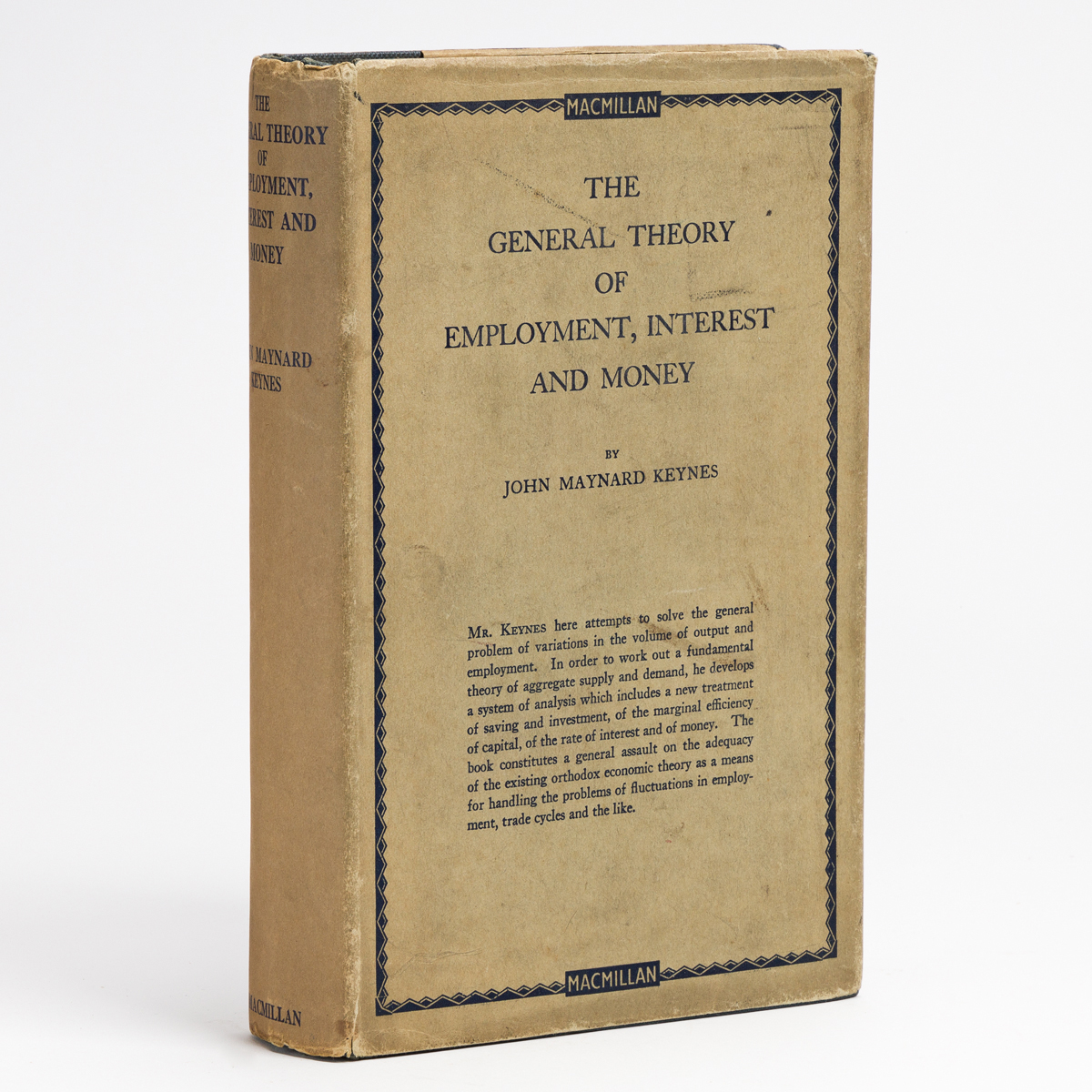

Here is not the place to elaborate on the reasons for the Crash, which we have explained thoroughly elsewhere. Nor is it necessary to repeat here the Marxist critique of Keynes’ magnum opus, his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. For this, we recommend our in-depth article on Marx, Keynes, Hayek and the Crisis of Capitalism.

What is worthwhile discussing here is the impact that Keynes’ ideas had in this period.

The General Theory was a work forged in the crucible of the Depression, with its previously unseen levels of mass unemployment. In it, Keynes correctly identified the downward spiral seen in a slump: unemployed workers had no wages to buy goods; the capitalists would not invest if they could not sell their goods; and with no investment, unemployment would go up – and so on and so forth.

To break this vicious cycle, Keynes concluded that state intervention was required to save and manage capitalism; that capitalists governments would need to step in at times of crisis to ‘stimulate demand’ by borrowing and spending. As mentioned above, this is the overriding legacy and fundamental pillar of what would traditionally become known as ‘Keynesianism’.

But what Keynes could never explain was why such crises occurred in the first place. Nor did he consider such an explanation necessary.

Unlike the libertarian free-market zealots who preceded him, whom he considered to be mere ‘apologists’ for capitalism, Keynes saw himself as a ‘pragmatist’. His job was not to justify capitalism theoretically, but to save capitalism practically – to save capitalism from itself.

With The General Theory, Carter writes in The Price of Peace, Keynes had “opened the door to a new world of political possibilities that both the financial establishment and its Marxist critics had believed to be impossible.”

“It meant that society could look very different than it currently did—but also that the prevailing order did not need to be destroyed or overthrown to be improved. It carried the seeds of radical transformation through the preservation of the existing social order and its institutions.” (Our emphasis)

As far as Keynes did offer an explanation for the crash, it was a purely idealistic one. The problem, he asserted, was simply a “loss of confidence”, brought about by herd instincts and “animal spirits”.

“Today we have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle,” Keynes wrote in an essay on The Great Slump of 1930. “At this moment the slump is probably a little overdone for psychological reasons.”

The solution was easy, Keynes asserted. Capitalist governments everywhere should just “join together in a bold scheme to restore confidence…which would service to revive enterprise and activity everywhere, and to restore prices and profits, so that in due course the wheels of the world’s commerce would go round again.”

There you go – just “restore confidence”! If only someone else had thought of that; then everyone could have avoided this whole “colossal muddle” and returned home in time for tea.

But this just highlights, once again, the idealism of Keynes and the utopian liberalism he embodied. It is true, ‘confidence’ plays an important role in the market economy, which operates anarchically, according to the volatile price signals provided by the ‘invisible hand’.

Under capitalism, however, this confidence has a material basis: the ability of the capitalists to make and realise a profit. If there are profitable markets for the bosses to exploit, and in which to sell, then confidence will be brimming. If not, as is the case with capitalism’s crises of overproduction, then confidence will dissolve and disappear.

It is this same idealism that led Keynes – and subsequent Keynesian acolytes – to go to the other extreme also: to see capitalism as a mechanical clockwork system, definable through abstract equations and models; a mere machine that could be managed by state bureaucrats from the top down.

And so it is today that mainstream economics textbooks teach students about the wonders of ‘macroeconomics’: the erroneous theory that central banks and Treasury officials can determine economic output by fine-tuning variables like interest rates and taxation levels; a theory that nowadays is repeatedly crashing up against the hard rocks of capitalist crisis.

Stimulus and austerity

Back to the Great Depression. More concretely, Keynes suggested that governments should make up for the shortfall in demand, caused by the collapse in business investment and household consumption.

They should do this, he suggested, by borrowing and spending. The key thing was to get money into workers’ pockets, which they could then use to consume other commodities, which in turn would stimulate private investment, and so on. In this way, Keynes outlined, governments could replace the vicious cycle of depression with a virtuous circle of growth.

Displaying the characteristic cynicism of an aloof liberal, Keynes was ambivalent as to how this money should end up in the hands of workers.

“It would, indeed, be more sensible to [pay workers to] build houses and the like,” Keynes stated in his General Theory. But if this were not possible due to “political and practical difficulties”, then the government should just “fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coal mines…and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again”.

In other words, the goal was not to plan the economy to meet the needs of society. No, the aim was merely to get profits flowing again into the coffers of big business, so that the stuttering engine of capitalism would restart.

Unfortunately for Keynes, his proposals were a nonstarter back home. In the run-up to the 1929 general election, the liberal economist had written an essay entitled Can Lloyd George Do It?, in which he called for a ‘Keynesian’ programme of government investment to tackle the scourge of mass unemployment in Britain, which had never gone away since the return to the gold standard in 1925.

But it was the Labour Party, not the Liberals, that went on to win the election, despite Keynes’ support for the latter. And instead of implementing his suggestions, Labour, in face of the crisis, reneged even on their own left-wing promises.

Faced with economic catastrophe, and under pressure from the bankers, right-wing Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald broke with his party, crossed the aisle, and formed a National Government. Austerity and attacks, not ‘investment’ and ‘growth’, were the only dishes on the menu.

The New Deal

And so it was that Keynes looked across the Atlantic for political support for his ideas, which he found in the form of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. After all, Roosevelt seemed to be on the same wavelength as Keynes regarding the psychological causes of the crisis, famously declaring that “fear itself” was the main problem facing society.

Having learnt the hard way that acerbic remarks led nowhere, Keynes changed tack and displayed a warm enthusiasm towards FDR. This can be seen in the series of letters that he wrote to the US leader throughout the 1930s, praising his New Deal programme, with chummy titles such as Dear Mr President.

“Dear Mr President,” Keynes began in December 1933, “You have made yourself the trustee for those in every country who seek to mend the evils of our condition by reasoned experiment within the framework of the existing social system.” (our emphasis)

Note the emphasis here. Once again, Keynes’ primary concern about the Great Depression is not its devastating impact on ordinary people’s lives. Rather, his fear is that this will provoke a revolutionary backlash; that the ‘Bolshevik influenza’ will spread if unemployment and poverty are left unchecked.

And so he continued in the same letter: “If you fail, rational change will be gravely prejudiced throughout the world, leaving orthodoxy and revolution to fight it out…This is a sufficient reason why I should venture to lay my reflections before you…”

By 1938, however, the cordial tone of Keynes’ correspondence had cooled. After several stalled starts and the occasional rally, the American economy had slumped again in the autumn of 1937. Roosevelt came under pressure from the big financial families, who believed that the government was getting too big for its boots. And instead of doubling-down on the New Deal, as Keynes suggested, the President was caving in to the demands of Wall Street.

Attempts to massage FDR’s ego had worked no better than Keynes’ earlier full-frontal attacks on Clémenceau and co. At the end of the day, these leaders all had one thing in common: they were big business politicians, who responded to the demands of the capitalists, not the scribblings of an English academic.

“[To] the president,” Carter notes, “Keynes was an impractical mystic. Though he insisted…that he ‘liked’ the British economist ‘immensely’, the truth was that FDR had been annoyed by the haze of high theory in which Keynes had enshrouded their conversation.”

“In particular,” the biographer continues, “FDR thought Keynes politically naive about the president’s relationship to Wall Street. He believed that a banking industry hostile to his reform programme was driving up the interest rates on government debt.”

“There is a practical limit to what the government can borrow,” Carter quotes Roosevelt as saying, “especially because the banks are offering passive resistance in most of the large centres.”

In the end, the Depression continued right up until the Second World War. Indeed, in the decade following the Wall Street Crash, the global economy saw repeated sharp and sudden falls – particularly in response to protectionist ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies being introduced by the different capitalist powers, all looking to export the crisis elsewhere.

The New Deal – the biggest living experiment of Keynes’ ‘pragmatic’ proposals – had failed. Only by mopping up workers into the army and the arms sector did unemployment eventually fall for good.

Events had demonstrated that the idea of technocratic state-managed capitalism could only successfully be implemented in times of war. This irony was not wasted on the ‘pacifist’ Keynes, who himself reluctantly remarked:

“It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case — except in war conditions.”

Bretton Woods and beyond

By the time WWII rolled round, Keynes was no longer persona non grata amongst the ruling class. It was clear to the establishment by now that the economist’s warnings over the Versailles Treaty and the gold standard had been correct. And he was gaining a steady stream of followers in academia and amongst the elites, thanks to the publication of The General Theory and his links to FDR.

Throughout the war years, therefore, Keynes was brought back into the fold of Whitehall, enlisted by the government to provide advice. And as with the First World War, this liberal ‘pacifist’ utilised his economic mind to help British war efforts.

First up was How to Pay for the War, a pamphlet published in 1940. In this, Keynes employed his new macroeconomic ideas to suggest how the state could maximise industrial output without causing inflation.

Of course, questions of nationalisation, workers’ control, and socialist planning did not enter into his equations. Instead, workers were asked to accept a system of ‘deferred pay’, in order to limit consumption and thus put a lid on demand.

These proposals were subsequently adopted by the government in its 1941 budget. Meanwhile, big business did not waste any opportunity to fleece the working class through profiteering and via juicy government contracts.

Later, Keynes also took part in the discussions that contributed towards the Beveridge Report. This laid the basis for the welfare state, established by the 1945 Labour government, which brought in ‘cradle-to-grave’ support and the National Health Service.

But Keynes’ work on these fronts was cut across by an even bigger project: designing the system of international institutions that would emerge from the war – the Bretton Woods system.

Despite suffering from ill health and old age, Keynes was sent to the Bretton Woods conference in New Hampshire, USA, in 1944 as the UK’s lead representative and negotiator. And he went in with a plan. Like all the best laid plans, however, his did not survive first contact with the enemy – in this case, the United States.

In creating a new global architecture for money and trade, Keynes believed that the most important thing was to avoid any major international imbalances. These, he asserted, were a fundamental source of tension between nations.

Measures were needed, therefore, to guard against large debts and trade deficits. Step one of Keynes’ three-part plan, then, was for the creation of an ‘International Clearing Union’. This, he suggested, would effectively force nations to import more if they had a trade surplus (via a revaluation of their currency), and vice-versa in the case of trade deficit (via devaluation).

At the same time, Keynes was adamantly opposed to any form of gold standard. Events had demonstrated that such a setup would be too rigid to accommodate the different directions and speeds that various national economies could – and would – move in. Instead, he called for, flexible, managed currencies (step two).

This should include, Keynes proposed, the creation of a new world currency, to be regulated and distributed by a ‘Supranational Bank’ (step three). This international central bank, in turn, would be on hand to help out any countries facing economic crises.

Keynes’ hope was that this would provide national governments with the freedom to carry out stimulus (as he had advocated in his General Theory), and avoid the disaster of deflationary austerity.

But Maynard’s plans were dead on arrival. As ever, Keynes’ bright ideas were completely abstract and utopian, entirely divorced from the reality of world relations as they stood at the end of the war. Britain, in short, was in no place to be telling its new big brother – US imperialism – what to do.

“In truth,” Carter writes, “the US government simply had no interest in creating an international order that would diminish American power. The Roosevelt administration was clear-eyed about raw-power realpolitik considerations.”

In the end, none of Keynes’ proposals were adopted. “Instead,” Carter continues, “all the nations that joined the Bretton Woods project would agree to make their currencies convertible into dollars at a fixed exchange rate. The dollar, alone among these currencies, would be convertible into gold.”

“Instead of a central international bank to regulate trade deficits and surpluses, an International Monetary Fund would be established to provide emergency loans in a crisis [with strings attached, always involving austerity and privatisation, not stimulus]. In addition, a World Bank would be established to assist with postwar reconstruction.

“Keynes had imagined an international regulatory apparatus to prevent predatory trade arrangements and financial crises. What he got was the gold standard with a bailout fund.”

These – the dollar standard, the IMF, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organisation (originally GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) – collectively are what is now known as the Bretton Woods system.

And far from representing the liberal internationalist ideal of equality and harmony that Keynes desired, this setup from the start was designed solely for the benefit of the real sovereign rulers of global capitalism: US imperialism.

As mentioned at the start, by the 1970s, the Bretton Woods project lay in tatters. Ironically, it was inflationary Keynesian policies of ‘demand-side management’ and ‘deficit financing’ in the postwar period that played a major role in its downfall.

American war spending on Korea and Vietnam, amongst other things, had made the dollar an unsustainable peg for the rest of the world’s currencies. The global economic crisis that hit in 1973-74 was the final straw.

Today, all of the remaining institutions of the Bretton Woods agreement are also in disarray. The relative decline of US capitalism; the rise of Chinese imperialism and protectionism internationally; and over a decade of crisis since the 2008 crash: all of these have reduced the WTO et al. to a laughing stock; an empty husk; a paper tiger.

Keynesianism after Keynes

Keynes died on 21 April 1946 at the age of 62. He lived to see the end of the war and the sweeping victory of the Labour Party in the 1945 election. But he did not live to see his ideas embraced by the ruling classes on both sides of the Atlantic.

The destruction of the war, and the hegemonic position that US imperialism held globally coming out of it, created the conditions for an unprecedented boom of world capitalism.

International trade was forced open by Washington, armed with its Bretton Woods institutions and regulations. With two-thirds of the world’s bullion in Fort Knox, the dollar was deemed ‘as good as gold’. This provided a further foundation for the massive expansion of global trade in the postwar period, just as British imperial power in Victorian times had facilitated the Gilded Age.

The surge in world trade was given a boost by the new markets established in the wake of national liberation movements in the ex-colonial countries. In turn, Britain and France gave way to a new American empire, with its epicentre located in the metropole’s Wall Street.

‘Keynesianism’ became the defining economic ideology of the postwar boom. As Carter explains in The Price of Peace, academic disciples such as John Kenneth Galbraith and Joan Robinson – located in the two Cambridges of Massachusetts (USA) and Britain, respectively – tried to keep Keynes’ liberal ideals alive and gain new adherents to his creed.

But the ruling class turned out to be far more ‘pragmatic’ than Keynes himself ever was. His ideas on macroeconomics, stripped of their utopian philosophical underpinnings, became standard practice in government ministries and university economics departments alike.

Keynesianism, in short, became just another weapon in the arsenal of the bourgeois and its political representatives; another set of tools for policy makers to deploy in times of crisis.

State borrowing and spending (‘deficit financing’); loose monetary regimes; and top-down ‘demand-side’ management: all of these became standard practice for governments of both the left and the right.

And so it was that even the reactionary Republican Reagan declared himself to be a convert. After all, Keynes’ ideas provided a useful theoretical cover for right-wing politicians looking to increase military spending and cut taxes for the rich – these too, they stated, would ‘stimulate demand’.

As capitalism descended further into its epoch of senile decay, however, these tools have become increasingly blunt and useless.

Far from ‘stimulating’ the economy, immense levels of government spending is required today just to keep the system alive. In the words of modern-day Keynesian, Larry Summers, we are in an era of ‘secular stagnation’.

The global economy is addicted to cheap money. Total worldwide public debt has shot up to over 100% of GDP, as a result of the 2008 crash and now the coronavirus crisis. But all this stimulus and spending brings with it the risk of inflation and instability – as the ruling class is currently finding out.

In another twist of fate, the biggest example of classical Keynesianism in history has been undertaken over the last decade in – of all places – China. One can imagine Keynes turning in his grave at the thought of the Chinese Communist Party becoming his greatest cheerleaders.

But just as with the New Deal, Beijing’s Keynesian programme has not worked either. State stimulus has become a stark case of diminishing returns. Government investment has resulted in ghost cities and roads-to-nowhere being built. Total Chinese debts, meanwhile, have ballooned to nearly 300% of GDP.

In The Price of Peace, Carter notes that the decades that followed the 1973-74 world crisis were wilderness years for true believers in Keynesianism. Instead, the so-called ‘neoliberalism’ of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman dominated the economic and political landscape.

Diehard Keynesians believed that the 2008 slump and ensuing Great Recession would pave the way for their return. But instead of enacting policies of ‘stimulus’ and ‘growth’, governments everywhere universally carried out programmes of austerity.

The most vocal advocates of Keynesianism, therefore, are no longer found in central banks or universities, but in the leaderships of the labour movement. And yet, as we have shown by charting out the history of Keynes’ life and ideas, the left should have no truck with these barren theories.

It is not hard to see, however, why Keynes’ ideas have such appeal to this layer, and to the neo-Keynesian zealots who preach about the wonders of ‘Modern Monetary Theory’. The liberal economist was offering seemingly ‘radical’ change – change that, at root, reflected only a maintenance of a broken status quo. And all of this, without the inconvenience of class struggle.

As we have already emphasised, just like the ‘pragmatic’ and ‘realistic’ reformist leaders today, Keynes had no faith in the working class to transform society. Indeed, his entire life was spent beseeching the elites, and displaying disdain for workers and the labour movement. Above all, the Englishman was terrified of revolution, which he wanted to avoid at all costs.

Grasp the root

Keynes closed his General Theory, Carter writes, “with an appeal to Marxists”:

“Do not discount the power of ideas to triumph over the economic interests of the ruling class [Carter paraphrasing Keynes]. The vested interests of the capitalists, he argued, did not reign sovereign over the great gears of human history; the beliefs and ideas of the people did.”

“They [Marxists] could choose to shrug off the suffering and dysfunction of the past two decades without resorting to violent revolutionary upheaval,” the biographer says, representing his subject’s views. “All they needed was to be convinced by an idea.”

But Keynes’ appeals to the socialist left were proven wrong. Despite all his efforts, and by his own admission, he “could never influence the course of events in time”.

“If Keynes’ ideas were so good and entrenched class interests were not blocking their implementation, why hadn’t anybody picked them up?” Carter rightly asks. “Because I have not yet succeeded in convincing either the expert or the ordinary man that I am right,” the tireless intellectual is reported to have replied to such a question.

This did not deter the Cambridge economist, however. “Compared to the persuasive power of good ideas,” Cartes states, before quoting Keynes, “the power of self-interested capitalists to stand in their way is negligible”.

And yet, as Carter aptly demonstrates in his biography, even the revered ‘genius’ Keynes was unable to persuade the ruling class. At every step, he and his utopian suggestions were rebuffed. His supposed ‘pragmatism’ proved to be the most hopelessly naive idealism.

“The arc of his public life from the outbreak of war to the British financial crisis of 1931 had been one long, fruitless attempt to bend European policy to his brilliance,” Carter summarises.

“As a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference, he had failed to persuade world leaders that a lasting peace in Europe required a collaborative public commitment to rebuilding the continent. Ineffective as an insider, he had tried his hand as an outside agitator, pressuring the government as a journalist, public intellectual, and media mogul. By 1932, it was clear that in this, too, he had failed.

“He had conquered the Liberal Party just in time for the Liberals to become irrelevant. Though his proclamations in The Economic Consequences of the Peace and The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill were now conventional wisdom for the man on the street, the fulfillment of his prophecies had driven his political allies from power….

“Great Britain’s break with the gold standard had given the country plenty of leeway to undertake a public works programme, but none had made the governing agenda. Everyone agreed the Treaty of Versailles to be a debacle, but nobody had fixed it in time to prevent disaster in Germany. [And then his proposals were shot dead at Bretton Woods by American negotiators.]”

The ‘power of the idea’, it seemed, could not overcome the material interests of the capitalists, who are driven not by ‘great ideas’, but by the cold economic laws and logic of capitalism: the endless drive for profit.

Ideas can be a truly powerful force. But only ideas whose time has come, as Marx explained: ideas that correspond with objective reality; that “grasp the root of the matter”; that become a “material force” by “gripping the masses”. It is this – the struggles and movements of the masses, not the ‘power of ideas’ – that is the real motor force of history.

Keynes and his ideas could never “grasp the root of the matter”: the inherently contradictory and crisis-ridden capitalist system. Instead, he wrote for the establishment, imploring them to adopt his programme in order to rescue capitalism.

That is why Keynes and Keynesianism must be rejected by the left and the labour movement. In place of this liberal idealism, workers and youth should study the revolutionary ideas of Marxism. Only in this way can we understand the world – and fight to change it.

‘The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes’ by Zachary D. Carter is available in hardback and paperback from Penguin Random House.