“To illustrate how volatile political loyalty can be, I told them about how the party membership cards in Bristol in 1932 had little holes in them where the photograph of Ramsay MacDonald had been cut out.” (Tony Benn, Diaries 1980-90)

There are many landmarks in the history of the British labour movement, which hold important lessons for today.

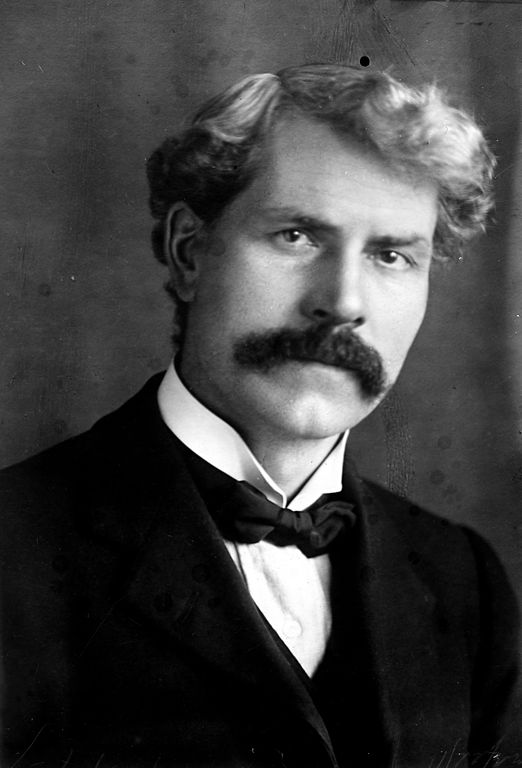

One that stands out – an event that is burned into the memory of Labour, as one of the greatest betrayals in Labour history – is when Ramsay MacDonald stabbed the labour movement in the back.

This was in August 1931, 90 years ago this month, when the then Labour Prime Minister crossed the floor to join the Tories and Liberals and form an austerity National Government. As a right-wing Labour leader, the traitor MacDonald found this as easy as moving from the second to the first class carriage on a train.

National interest

Ramsay MacDonald stood, of course, for the ‘national interest’ – the national interest being the interests of the bankers and big business. He, along with the few other Labour traitors who split to form the National Government, had the full backing of the ruling class.

“Mr Snowden [the Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer], with rare though belated courage, has shown that he at least knows where that duty lies,” thundered the august London Times, the mouthpiece of British capitalism, in early 1931. “And, whatever the attitude of the rest of his party, the public will never grudge him any assistance which he may need in carrying through his difficult task.”

Then as now, capitalism was experiencing a deep global slump, ushered in by the Wall Street Crash of September 1929.

The resulting collapse in the productive forces internationally caused spiralling unemployment: in Germany seven million were out of work; and in the USA, 25% of the workforce was unemployed.

In 1929, just over one million were already unemployed in Britain. But by 1931, this number had risen to 2.7 million – 22% of the insured workers. Production had declined by 8%, falling to below that of 1913 levels. The growing budget deficit threatened to force Britain off the gold standard.

Under these circumstances, the MacDonald Labour government, elected in early 1929 with Liberal support, proved to be a government of crisis.

Steeped in the gradualism of Fabianism and unprepared to challenge capitalism, the Labour leaders had sought to work within the confines of the system. Such a policy, on the basis of growing economic difficulties, resulted in their early reforms being replaced by counter-reforms. By their actions, they became the handmaidens of capitalism, eager to do its bidding.

Whereas the working class demanded measures to reduce unemployment, the ruling class demanded savage cuts in the ‘national interest’, in order to put industry back on its feet.

Economies

Under pressure, the Labour Cabinet bent the knee to big business and unanimously supported a Liberal motion to create the May Committee.

Headed by Sir George May, formerly Chairman of the Prudential Assurance Company, this committee had the task of examining the dire situation and coming back with ‘economies’ – i.e. cuts. The Committee, in the words of Beatrice Webb, consisted of “five clever, hard faced representatives of capitalism and two tame trade unionists”.

As expected, its report, published in July 1931, recommended draconian cuts in government spending in order to balance the books, assist industrial recovery, and promote profitability, in line with Snowden’s policy.

These measures included a 20% cut in teachers’ pay; a 25% cut in service pay; and a 20% reduction in unemployment benefits, imposed through a means test. These ‘economies’ amounted to £96.5 million.

On 11 August, a Labour subcommittee of ministers – MacDonald, Snowden, Henderson, Thomas, and Graham – met to consider the recommendations.

“We arrived,” stated Jimmy Thomas, “and were informed of the serious financial collapse; we were told of all the negotiations which had taken place with the bankers, of the necessity for a loan, and of the serious crisis that had arisen.”

“So satisfied were we all that, before the Cabinet were called together, we felt that on our own responsibility we should issue a statement that a balanced Budget was essential, and we intended to bring it about.”

Thomas added: “And coupled with the statement was an intimation that sacrifices would be demanded from all.”

They instead recommended cuts of some £78 million, including attacks on the unemployed, which the majority of the Labour Cabinet actually accepted.

“There was not one of us who did not feel very keenly the hardships of the cuts, and especially those to be imposed on the unemployed,” explained Thomas. “The problem, however, facing us was not the immediate hardship, but the position that would inevitably arise if no action were taken.” (Thomas, My Story)

In August, despite the opposition of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), these anti-working class proposals were accepted by the Labour Cabinet.

But the proposed cuts did not go far enough to ‘restore confidence in sterling’ and prevent a run on the pound. Under pressure from the Bank of England and big business, the Cabinet were forced to look for further cuts.

Despite representation from the unions, MacDonald replied that “nothing gives me greater regret than to disagree with old industrial friends, but I really personally find it absolutely impossible to overlook dread realities, as I am afraid you are doing.”

Beatrice Webb, the Fabian, described the TUC General Council as “pigs”, saying “they won’t agree to any ‘cuts’ of unemployment insurance benefits or salaries or wages”.

Despite their subservient attitude, some within the Cabinet baulked at further cuts. For them, the few extra millions proved too difficult to swallow. To quote the Bible, they swallowed a camel, but strained at the gnat. The Cabinet split, with a minority in opposition.

“It is true that some of our colleagues felt so keenly on the unemployed cuts,” wrote Jimmy Thomas, “that they thought it necessary to hold a private meeting between themselves on the Saturday prior to the Sunday Cabinet.”

“And when the final choice had to be made it was evident that although a majority were in favour of imposing cuts, there was no hope of carrying a united Cabinet, and a break-up was then inevitable.”

“It is only fair to say,” Thomas continued, “that MacDonald made a supreme effort to keep us together, and only when he found this impossible did he make up his mind to carry on himself.”

The monarchy

This belated opposition forced MacDonald’s hand. Determined to overcome the crisis at all costs, a day after the fateful Cabinet meeting, he went to see the King, and opened up discussions with the Tory and Liberal leaders with a view to establishing a National Government.

As can be seen from the records, the monarch, King George V, was very much part of the plot to form the National Government. MacDonald and the leaders of the opposition parties were in constant touch with the palace, which acted as a friendly broker. “In a strictly constitutional capacity,” noted The Times, “he [the King] has rendered a signal service to his people.”

There is a lesson in this. In the future, in a similarly critical situation, the monarchy would again be used in the same vein. Behind the scenes, the monarchy is very much involved politically in pressuring ministers over various questions. This pillar of the establishment possesses extensive ‘reserve powers’, which will be used when the time comes.

The King met both Baldwin, the Tory leader, and Sir Herbert Samuel, the Liberal leader, to discuss the ‘national interest’.

In order to use the authority of the Labour leaders to confuse and disorientate the working class, the opposition leaders wanted MacDonald to maintain the premiership. Sir Herbert Samuel cynically informed King George V that:

“In view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working classes, it would be to the general interest if they could be imposed by a Labour government.

“The best solution would be if Mr Ramsay MacDonald, either with his present, or with a reconstituted Labour Cabinet, could propose the economies required. If he failed to secure the support of a sufficient number of his colleagues, then the best alternative would be a National Government composed of members of the three parties.

“It would be preferable that Mr MacDonald should remain Prime Minister in such a National Government.”

MacDonald then informed his Labour colleagues that he had seen the King, and that he had agreed to continue as prime minister with the support of the Tory and Liberal leaders, who would serve under him.

Of course, he could have simply refused to implement the cuts and resigned. But Thomas jumped to his defence:

“Here let me say that the meanest of all the suggestions that we should resign was that the other parties should bear the odium of doing what we absolutely and unanimously agreed was necessary!

“Some of us, myself included, refused to transfer the responsibility which we knew was ours to the shoulders of other people for mere Party considerations.”

“Looking back,” Thomas concluded, “I have no regrets for the action I took in the fall of the second Labour government.”

“I am convinced that what was done saved the country; everything that has happened since has justified it, and although today there are still those who would revert to party government and party warfare, the position of a very troubled world convinces me that a profound mistake would be made.

“It is only right I should say that, making allowance for the different interests and political outlooks that had divided us for years, from the day the National Government was formed, no body of men could have been more detached from their own particular party, and none more determined to work for the common good.”

This accurately sums up Jimmy Thomas’ outlook, as well as those who stabbed the party in the back and split to join the National Government of Tories and Liberals. These backstabbers were traitors to the working class and proven loyal servants of capitalism. They were well rewarded for services rendered.

Split

Following the formation of the National Government, Snowden told MacDonald that “tomorrow every Duchess in London will be wanting to kiss me”. The ruling class were likewise delighted with the outcome. “All concerned are to be warmly congratulated on this result,” commented The Times.

A few years earlier, in 1925, Leon Trotsky commented: “It is not hard to imagine the careerist depravity that reigns in the ministerial heights of the British Labour Party!”

He went on to describe the role of these careerists:

“These pompous authorities, pedants and haughty, high-falutin’ cowards are systematically poisoning the labour movement, clouding the consciousness of the proletariat and paralysing its will.” (Leon Trotsky, Where is Britain Going?)

MacDonald’s former colleagues were stunned by the speed of events. They had all come to accept the need for sacrifices and a balanced budget, but – according to Henderson – they had been kept in the dark.

When the split came, right-wingers Henderson and Clynes did not follow MacDonald, but remained inside the Labour Party to prevent it falling into the ‘wrong’ pair of hands – namely the left wing.

While the Labour leaders wept over the “great loss to the labour movement” of MacDonald’s departure, the rank and file of the party forced the national executive to expel MacDonald and the other traitors.

Election

After forming the National Government, MacDonald needed to take advantage of the split and consolidate his mandate. He therefore called a panic general election in October.

With the Labour Party in disarray, the result was a landslide victory for the National Government of Tories, Liberals and National Labour – which gained 554 seats and 70% of the vote.

The Labour Party, which was completely disorientated by the betrayal, was decimated at the polls, capturing only 52 seats. The total Labour vote had dropped by two million. But there were still 6.5 million who had still clung to the party.

The ruling class were overjoyed by the election result. “The General Election has given the National Government the greatest majority ever recorded in British political history,” proclaimed The Times. “The verdict of the electorate is therefore as deliberate as it is decisive.”

According to the Labour traitor, Philip Snowden, later Viscount Thurso:

“The National Government took up the task when the deserters had left. The work of the National Government has saved the nation. It will complete its task and return Great Britain once more to its pre-eminent position in the world.

“Its work has already established confidence in industry at home and abroad in our financial honesty. Trade is beginning to improve. The workers can now look forward to employment instead of the dole.”

Of course, the reality was different. Unemployment remained at historic levels throughout the 1930s, and was only ‘resolved’ with the outbreak of war. Working-class communities were blighted by the capitalist crisis and the austerity that accompanied it.

Sir Henry Betterton, the Minister for Labour in the National Government, reported that in the two years to the end of October 1933, the economies obtained by the reduction in unemployment benefit of 10% had been £26.75 million, along with £27.75 million from the operation of the means test, making a total of £54.5 million wrung from the most poverty-stricken areas of the country.

Radicalisation

The betrayal served to push the ranks of the Labour movement far to the left. Even the surviving Labour leadership was pushed to the left – in words at least.

“The revulsion from MacDonaldism caused the party to lean rather too far towards a catastrophic view,” warned Clement Attlee.

“The attitude of the rank and file of the party seems to me to be extremely dangerous at the moment,” wrote Stafford Cripps. “There is a strong tendency to discard the realities of the situation.”

The Independent Labour Party swung politically between reformism and revolution. The 1932 Labour conference, cleansed of MacDonald and co., saw a dramatic radicalisation, proclaiming that “the main objective of the Labour Party is the establishment of socialism”.

Harold Laski, a leading Labour theoretician, asked whether “evolutionary socialism (had) deceived itself in believing that it can establish itself by peaceful means within the ambit of the capitalist system.”

Another leading left figure, Stafford Cripps, in a pamphlet entitled Can Socialism Come by Constitutional Means?, warned that: “The ruling class will go to almost any length to defeat Parliamentary actions if the issue is the direct issue as to the continuance of their financial and political control.”

Cripps then went on to advocate emergency powers for a Labour government to tackle the crisis.

The Independent Labour Party, which was a key component of the Labour Party, became increasingly radicalised. At its Easter conference, a motion was passed that stated:

“The class struggle which is the dynamic force in social change is nearing its decisive moment…There is no time now for slow processes of gradual change. The imperative need is for socialism now.”

The ILP conference also debated the question of whether or not to disaffiliate from the Labour Party, with a large section voting to give the party an ultimatum over its standing orders for the parliamentary party.

This organisational issue – the independence of the five ILP MPs from the discipline of the Parliamentary Labour Party – was the pretext for the split. At its special conference in July 1932, given the lack of response from the Labour Party, the ILP voted to disaffiliate.

While the ILP had the support of 100,000 and had a group of MPs, it lacked clarity and perspective. It eventually dwindled in support and later rejoined the Labour Party.

Marxism

Today the Labour Party is in an existential crisis. The defeat of Corbyn and the reemergence of the right has plunged the party into civil war. The aim of the right wing is to drive out the left wing. As a result, some 150,000 have already left the party in disillusionment.

Some have therefore raised the idea of a new left party. But unlike in 1932, there is no radicalised leftward-moving ILP; and the unions seem very much committed to the party. There are certainly no left MPs who are raising the possibility of a new party. In fact, many are seemingly keeping their heads down.

Whatever the immediate outcome of the struggle within the Labour Party, the class struggle in Britain is set to intensify. There is massive dissatisfaction and bitterness within the working class, and especially amongst the youth.

The trade unions are going to be shaken from top to bottom. Already Unison, the biggest union in Britain, has shifted to the left. This is a sign of things to come.

The right wing’s control is based on inertia. It is a support built on chicken’s legs. The deep crisis of capitalism – particularly acute in Britain – will transform and re-transform the labour and trade union movement. The ground beneath the right wing will be torn asunder.

We must learn from the past. There is no way forward on the basis of capitalism, which can only offer austerity and cuts in living standards.

This is preparing the way for explosive events, in which the ideas of Marxism will find a greater echo. The forces of Marxism, in Britain and internationally, will grow in leaps and bounds.

Our task is to prepare ourselves for this stormy period that lies ahead.