On 3 October, two million marched through the streets of every major city in Italy, demanding an end to the genocide in Gaza. Crucially, many of those protesting were workers, participating in the biggest political strike the country has seen in decades.

This kind of action is said to be ‘impossible’ by the sceptics and pessimists at the top of the labour movement, whether here or in Italy. Indeed, the leadership of the largest Italian trade union confederation (CGIL) tried to put every brake it could on the movement.

And yet, despite this, the ‘impossible’ has now happened.

The events of 3 October mark a turning point for the Palestine movement – and the cause of the working class – internationally. Without this mass mobilisation, Trump would not have felt the pressure to push his ‘peace plan’ on Netanyahu so forcefully.

Such mass action is precisely what could and should have happened in Britain by now too. Instead of mealy-mouthed excuses about the ‘passivity’ of workers (500,000 of whom marched through London on the last national demo for Palestine), the trade union leaders should have been proactively organising rank-and-file activists and members from day one.

In light of these developments, it’s time to rediscover our own fighting class traditions, so long buried under a pile of class-conciliation rubbish.

Militancy and international solidarity, like that seen across Europe recently, is not alien to the labour movement here. British workers have taken strike action, and even threatened a general strike, to halt the imperialists’ war machine before – most notably with the case of the Jolly George cargo vessel in 1920.

Radicalisation and revolution

The First World War – which was supposed to have been ‘over by Christmas’ in its first year – had, by the end of 1918, produced deep bitterness and radicalisation.

On the one hand, many millions had gone through hell in the war, either in trenches or on the home front. Workers had endured a ban on strikes, but could see that the bosses were free to rake in war profits.

Yet despite honeyed promises from Prime Minister Lloyd George, soldiers came back not to a ‘land fit for heroes’ but to the same old exploitation as before, further intensified by Britain’s declining position in the world.

On the other hand, news of the Russian (Bolshevik) Revolution of 1917 – where workers like them had fought the capitalists for power, and won – had begun to ripple across the whole continent. This had an enormous radicalising effect in several key industrial areas in the country.

This anger and political inspiration combined explain both the fiery strike wave that hit Britain in 1919, as well as the capitalists’ furious efforts to crush it.

The bosses did not stop at their own borders to fight the working class. Feeling their fundamental interests threatened (and sensing a golden opportunity to carve up Russia for themselves), the British imperialists sent troops to Russia under false pretexts, in order to overthrow the fledgling Soviet government.

Britain’s charged atmosphere was also reflected in the army, however. The result was several mutinies, as troops resisted the generals’ orders to go to Russia. In the end, this forced the British imperialists to withdraw their troops from Russia’s north, at least for the time being.

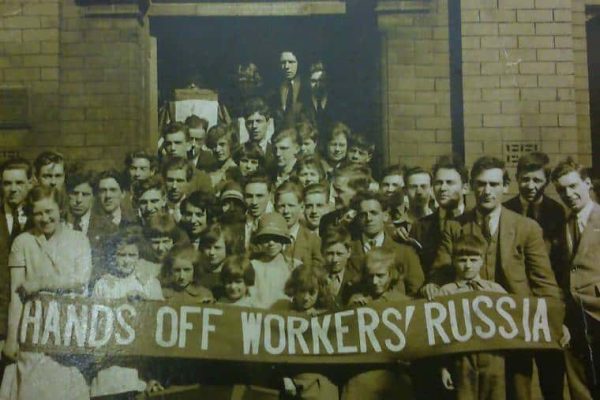

Hands off Russia!

It is hard to imagine today the level of radicalisation that had built up in Britain at that time. But even then, the mood amongst workers, although very sharp, was uneven. Not all layers of the working class were drawing conclusions at the same tempo.

In reality, any lag in revolutionary consciousness was largely a result of the vacillations of the labour leaders. Initially these ladies and gentlemen had backed the ‘Great War’ and their own imperialist ruling class. In 1918, meanwhile, they were at best lukewarm towards the nascent Soviet state.

As a result, when several small groups of socialists and communists formed the ‘Hands Off Russia’ campaign, they initially found the work of agitation quite hard going.

One area where the group gained plenty of sympathy was London’s East End docklands, where the group was strongest. Melvina Walker, a former servant and dockers’ wife, was particularly popular, regularly drawing crowds when she spoke in Poplar.

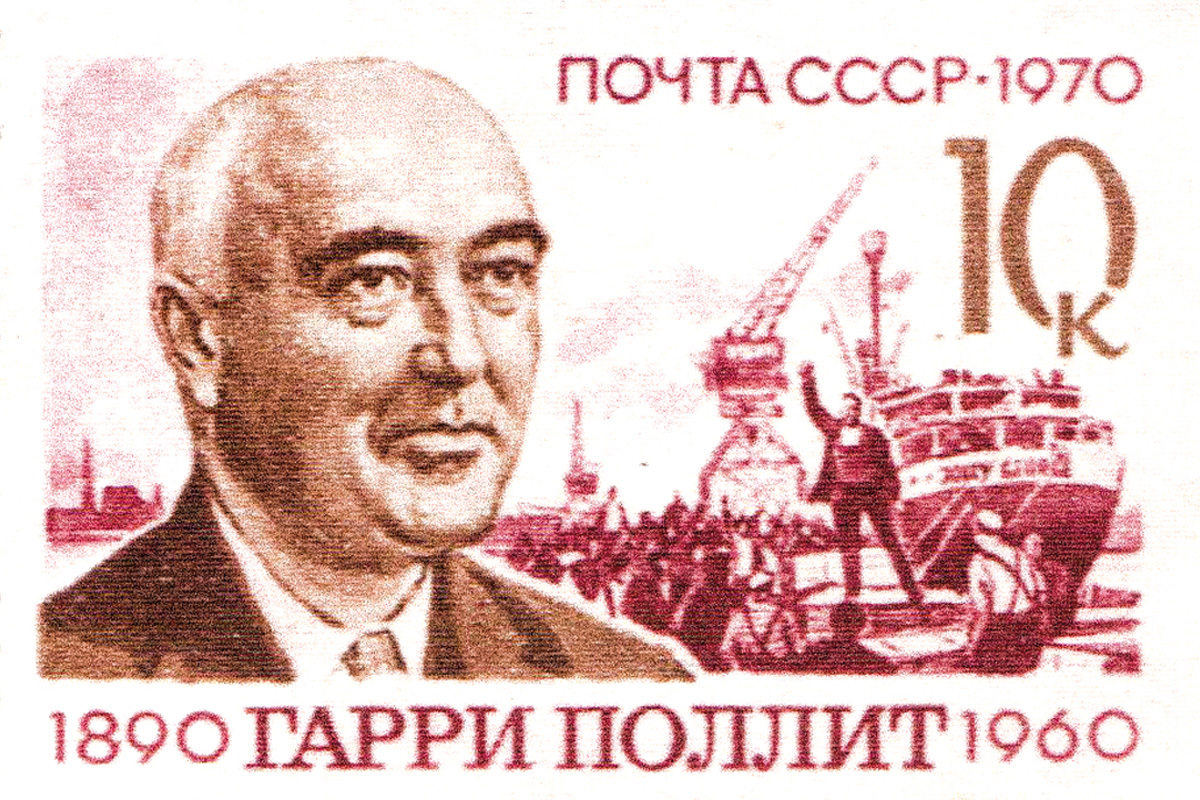

Direct action was hard to come by, however. Harry Pollitt, who went on to become the general secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, was sacked from his job after refusing to load munitions for counter-revolutionary Poland. But very few other workers were willing to take a similar stand at the time, due to the double rate offered for such jobs.

Several other boats were loaded from these docks, with only isolated incidents preventing munitions from reaching anti-Bolshevik forces. In one case, there was a fortuitous collision in the Thames, caused by an argument between anti-war sailors and a pro-war captain. In another, an accident at sea sank some barges along with all their cargo.

But these were exceptions to the rule, with no examples – as yet – of mass action being taken.

Fertile soil

This lack of militant action was not due to any lack of sympathy with the cause of the Soviets.

Certainly not every docker was a full-throated Bolshevik. But in the main, workers were suspicious of war given their own experiences. And they sympathised with a revolution that had promised peace.

Lenin’s pamphlet, An Appeal to the Toiling Masses, for example, practically flew out of campaigners’ hands in those days.

Initially, however, on the whole, this sympathy was mostly passive. This was a product of the conditions that prevailed in Britain at that time, and the aforementioned efforts of the bosses to keep industrial peace.

There were stormy strikes in this period. But in the main, these were fought to claw back something of a civilised life from the bosses. A political strike in defence of the Soviet state was a much bigger risk – one that many workers were still deciding whether or not to take.

That indecisiveness came to an end in 1920, as rumours began to circulate that Britain would not just send munitions to aid Poland, but troops as well.

The idea of sending troops into yet another slaughterhouse – this time to strangle the infant workers’ state in Russia – whipped up the mood in the British working class like nothing else could.

Here was proof, as the workers correctly saw it, of yet another war for the capitalists and imperialists. Even the least sympathetic workers had no interest in seeing themselves or their sons killed in another nakedly predatory overseas conflict.

Now the Hands Off Russia activists found fertile soil for their agitation. Consequently, the dockers loading the Jolly George responded en masse, refusing to load a single bullet onto the boat, which was bound for the Polish-Soviet front.

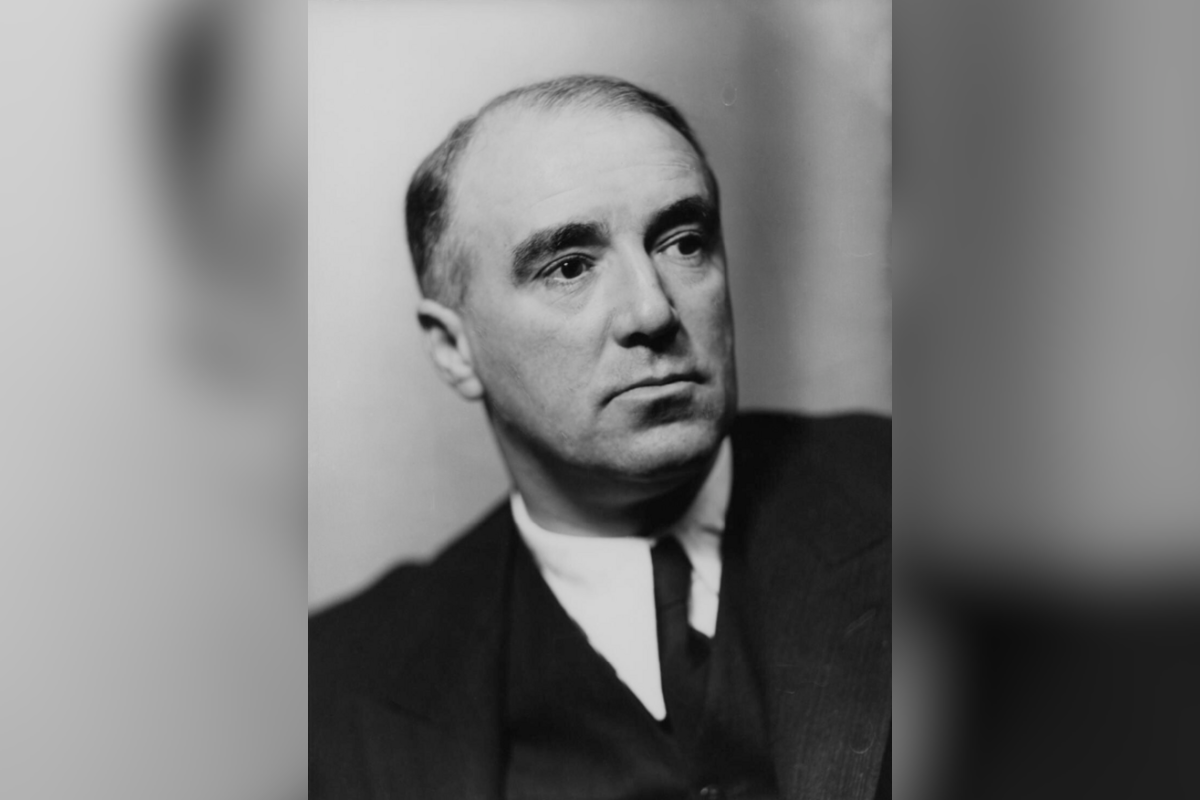

Walking off the job, workers demanded the backing of their union for the strike action they’d taken – appealing to infamous Labour right-winger Ernest Bevin, at this time a union leader. Incredibly, thanks to the obvious strength of feeling across the docks, they got it.

Without the cooperation of the workers, and with the possibility that reprisals would cause more dockers to strike, the Jolly George was forced to leave harbour without its cargo.

Slumbering giant

The floodgates were now open. Just like in Italy today, industrial action had been taken to grind the gears of the imperialists’ war machine. And the effect was electric.

Feeling the enormous pressure from below, the trade union and labour leaders were forced to respond.

The dockworkers’ union declared it would boycott all munitions shipments for use against Russia in ports across the country. Motions of solidarity with the Soviet state – demanding action to prevent Britain’s entry into the civil war – began to flood through trade union and Labour Party branches alike.

When the British government actually did threaten war with the Soviet state, in response to the Red Army approaching Warsaw in August, this fanned the flames of anger amongst the rank and file of the workers’ movement.

The labour leaders had to issue a direct ultimatum. Either Parliament must withdraw their threats of war, or the Trades Union Congress would mobilise all the workers under their banner and call a general strike to halt it themselves.

In preparation, the labour leaders set up a national coordinating body, the National Council of Action, with local councils called across the country to organise the movement.

Within days, around four hundred councils of action formed, ready to mobilise millions of workers. This demonstrated the heights to which radicalisation had risen.

In the end, owing to the unexpected defeat of the Red Army at Warsaw, this threat was never carried out. This came much to the relief of the trade union leaders, who knew full well they risked awakening a sleeping giant: the organised working class.

Nevertheless, this episode shows how such a process can occur; how a seemingly stable country can be brought to the brink of an explosion.

Over one hundred years later, we are seeing the same pressures building in society, with similarly volcanic events erupting to the surface in Italy, across Europe, and all over the world.

Unstoppable force

Much like in Italy today, the mass anger that exploded onto the scene in Britain in 1920 was a product of the war and the horrors it had caused. And it broke to the surface in spite of the trade union leaders’ passivity, forcing them to position themselves – reluctantly – at the head of the movement.

The key fact is that this mood already existed. All that was needed was a spark to alight this powderkeg.

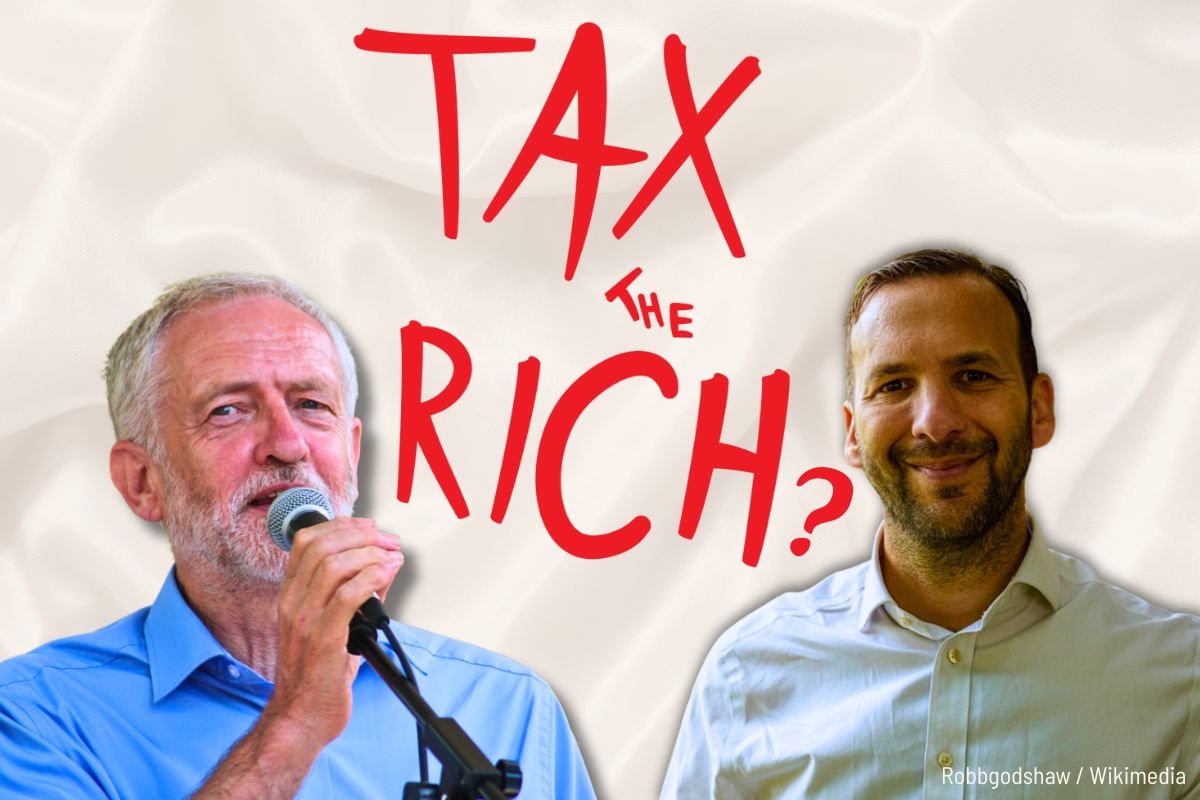

Today, this same anger exists – not just in one country or another, but across all of Europe. Workers have endured decades of austerity and attacks. Meanwhile, the capitalists have grown wealthier and wealthier. The foundations for social stability have been eroded everywhere.

Millions can see that the same elites who make their lives a misery at home have also aided and abetted the slaughter abroad, all for their own narrow interests. Ordinary workers are rightly sickened and disgusted by this sorry spectacle.

Italy has proved that the conditions for another ‘Jolly George’ exist today in all the imperialist countries. For the ruling classes, this spectre of militant class struggle is a terrifying prospect.

For us, the revolutionary communists, by contrast, the example of the Italian workers is a cause for inspiration and optimism.

The general strike for Gaza in Italy demonstrates concretely that there is a potentially unstoppable force within society; a power that can transform and turn around even the darkest, bleakest situation: the working class, organised and mobilised.

Going forwards, in the class battles to come, this force will need to be called upon once again.

From a potential resumption of the genocide in Gaza, to the near-certainty of savage cuts in the government’s upcoming budget: the heavy battalions of our class must be prepared for the struggles ahead. The passive ‘wait-and-react’ approach of the current trade union leaders will not suffice.

Above all, this means understanding the root cause behind all these social ills and struggles: the rotten capitalist system. And it means having confidence that the working class, armed with a clear revolutionary programme, has the power to put an end to all this misery and barbarism, once and for all.