Many of the standout events from the history of the class struggle in Britain were led by the miners, who formed the militant, heavy battalions of the workers’ movement.

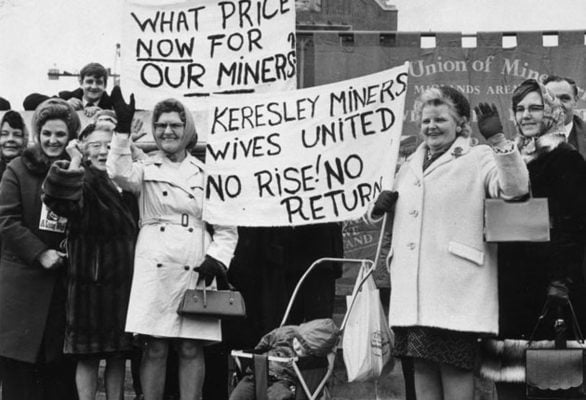

Throughout all these struggles, including the 1926, 1972, and 1974 miners’ strikes, working-class women fought shoulder to shoulder with the men.

Heather Wood – who became the chair of the Easington women’s strike support group during the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 – grew up in a community of class fighters, both male and female.

She remembers local women blockading the main street with their prams when she was a small child, demanding that the National Coal Board fit indoor bathrooms and toilets in the colliery houses. And they won!

The women of the mining communities across Britain really came into their own in the 1984-85 strike.

Across the pit towns and villages, it was well understood that the miners were fighting for the future of the whole community. The closure of the pits would mean social decimation and decay for generations to come.

This grim prediction has proved completely correct. Between 1981-2004, 222,000 jobs were lost in mining and related industries.

Today, in ex-pit towns and villages, there are just 57 jobs for every 100 working-age residents, compared to a national average of 73, or 88 in big cities. It’s no exaggeration to say that the Thatcher government laid waste to entire swathes of Britain’s industrial heartlands.

Support networks

Men and women who were active at the time say there is no way the strike could have shown such resilience, and have been so prolonged, without the ardent support of local working-class women. Wives, sisters, mothers, and friends of the striking miners did everything they could to deliver victory.

They set up support groups under the national banner of Women Against Pit Closures (WAPC), alongside countless local initiatives. In East Durham alone, there were 18 different support groups.

Initially, the role of these groups was predominantly to keep communities fed during the strike.

While some women worked, many were based in the home: cooking, cleaning, and raising children. Initially, women socialised these tasks, transferring them from the home to the community, and set about feeding the miners and their hungry families.

Free community cafes were set up, and thousands of food parcels were provided. In the North East alone, women’s groups fed 5,000 people, five days a week.

Women soon began to branch out beyond what they could offer domestically, however. They trained and educated themselves to be able to offer legal and benefits advice – essentially acting as local Citizens Advice Bureaus.

Support lines were set up, where men would call in the night after their wives had gone to bed, expressing how terrified they were about not being able to feed their families, or heat their homes. The practical and emotional support that women offered was invaluable in maintaining morale.

Political role

Women’s role was not solely in these traditional realms, however. As the strike raged on, they began to play an increasingly political role.

Women from working-class communities went out on the picket lines, standing shoulder to shoulder with the miners and facing head-on the police brutality rained down by the state.

They went on speaking tours all over the country, raising money for the miners, and drumming up support for their struggle.

This was essential work. The Thatcher government was trying to starve the miners back to work, having cut their entitlement to welfare benefits. This came alongside a vicious propaganda campaign against the strike by the entire British establishment.

Initially, just a few bold women took on these responsibilities. Many were reluctant to speak publicly. But before long, others were needed to pitch in, as it was too much work for just a handful of women.

There is a story of one very shy woman, who ended up speaking on a platform at a huge rally in Middlesbrough, alongside labour movement stalwart Tony Benn.

The crowd went wild in support of her. It was clear that she wasn’t used to speaking on such a platform. But following this experience, she grew in confidence, went to every rally and picket, and was no longer frightened of speaking up.

The role these working-class women played is inspiring. And the impact that these experiences had, both on the women themselves and their entire communities, is rich in lessons that we can take forward into the class struggle.

While some women who participated had previously been involved in politics – having been members of the Labour Party, their union, or revolutionary organisations like the Militant Tendency (forerunner of the RCP) – the vast majority had not.

Oral histories tell of women who had not been interested in politics, and had never dreamt of addressing a large public gathering, but who courageously rose to meet the challenges with which they were confronted in the course of this struggle.

Ann Lilburn from Northumberland, for example, became the national chair of WAPC. Until the miners walked out, she had never even spoken at a village hall. But by the summer of 1984, she was leading a rally of 23,000 women in London.

Consciousness transformed

One common theme in the testimonies of these women is the euphoria that is often described in all key moments of class unity and revolution.

So often, we, the exploited and oppressed, feel powerless and helpless living under capitalism. But in moments of united class struggle – when workers begin to feel a sense of their power – this can fall away very quickly.

A WAPC meeting was held at Barnsley Civic Hall, with more than 10,000 women present. Jean Miller from the Barnsley support group described how: “This was truly the most electrifying experience of my life. The atmosphere was tremendous. There were so many women in there it felt as though the floor was going to collapse.”

Maureen James, whose father was a Durham miner, described the effect this struggle had on her and the other women in her community:

“It changed my life. It showed me solidarity. It gave women a voice they never had before. And I think the men started to respect that women could do more. The amount of women who became politically active after the strike, who had never left the kitchen sink before – they were standing on platforms, they were doing marches. And that has helped my generation.”

This change in the dynamics between working men and women is echoed by miners’ wives in countless quotes. Previously, traditional gender roles had dominated, with women managing the home and men going out to work.

When two women went to the Easington Miners’ Lodge to propose setting up a support group, they had to stand outside for 30 minutes while the men debated whether to let the women enter the meeting.

But with men on strike and women either going out to work to bring in an income, or touring the country giving speeches, this began to change. Men started doing much more housework and had more time to spend with their children.

Overcoming divisions

There are some who say that divisions between men and women are embedded in our DNA, and are an inevitable, eternal truth of human biology.

But the events of the Great Miners’ Strike refute this suggestion. Within a few short months, on the basis of changed circumstances and experiences, relations between men and women within mining communities began to shift. Workers’ outlook – of themselves, others, and the world around them – was transformed.

One miner’s wife described this process:

“I felt like and saw myself as a clockwork doll, doing my duties every day. Wake up, clean the house, go to the shops, pick kids up from school, make tea. Everything was built around [my husband] Pete and the kids. I don’t clean up now, he does it. There’s things I never thought I’d do; things I never thought I’d say. And I just can’t get out of them habits now. It’s not habits – I’m a stronger person now.”

The ruling class actively seeks to divide the working class by promoting sexist attitudes and ideas. The profound alienation that can exist even between husband and wife is stark. But in the course of the class struggle, by uniting and fighting together, these seemingly intractable divisions can be overcome.

In the course of the strike, women threw themselves into collective study – discussing politics and debating union matters.

And as their role in keeping the strike going became more indispensable, they began to be seen in a new light by the striking men. Miners often made moving speeches from public platforms, saying they had not really known their wives before this strike.

Of course, this change was not universal. Some men did not start doing the housework, nor did they discover a new level of respect for their wives. Some women did not get involved in politics or flourish in these stark conditions.

But nonetheless, the change was remarkable, and was felt widely. One woman’s testimony aptly sums this up:

“A lot of men didn’t change, and a lot has been made of that. But for me, the important thing is not to look at those who didn’t change but to look at those who did. They were a significant enough number to make it clear to me that such changes are not only possible, but are an inevitable part of social change.”

Through changed circumstances, with men and women joining together in struggle, age-old prejudices – produced and reinforced by class society – can begin to be challenged and curbed.

Today we live in a society that relies on women taking on the drudgery of domestic labour, and suffering countless other forms of oppression in their daily lives.

The experience of the Great Miners’ Strike shows that collective struggle can begin to cut away at the sexism that pervades class society, and provides a glimpse of how a future socialist society – on the basis of a fundamental change in our material conditions – could transform consciousness, including the relations between men and women.

And it wasn’t only relations between men and women that were improved by the strike.

At the time, a lot of mining villages had little experience of other cultures and ethnicities, and some people would casually use racist terms. This could have been a problem when the women went door-to-door fundraising in places like East London.

Heather Wood explained that instead of lecturing the women about why this was wrong, she told them they should just wait and see who donates generously.

As she had expected, the Asian community showered the women with money, food, and drinks. The group ended up staying in London an extra day to make a point of attending a mass anti-Apartheid demonstration.

Consciousness

In Reform and Revolution, Rosa Luxemburg explains how participating in the struggle for reforms within capitalism can play a monumental role in the development of revolutionary consciousness. This is clear to see among the women in the mining communities.

To begin with, most women supporting the strike were not politically motivated. They were just trying to feed their families and safeguard their children’s futures.

But soon the full force of the state was aimed at these communities – as seen with the Battle of Orgreave, alongside countless other egregious attacks. It was impossible for these women to avoid drawing broader political conclusions.

There are countless tales of brutal police repression being aimed at women. They were dragged, pushed, hit with truncheons, punched, kicked, spat at, insulted, and threatened with sexual violence.

Women who were not originally involved in the struggle were drawn in by their disgust and hatred of the police, having seen the horrific treatment of these communities.

Some women said they were not afraid of the police – but many others were petrified, having experienced the violence these thugs were capable of.

The bravery on display was truly remarkable. It is striking that although people were afraid, they were in no way deterred from continuing to stand up and fight.

For many, the extent of the state’s repression was a rude awakening. Heather Wood reflects on this:

“One of the biggest learning curves for all of us was how the state can operate against you and what they can do – like the constraints they can put on you, or that people can be locked up for no reason. I think it taught a lot of women about capitalism.”

Period of defeat

Almost universally, the women were against the miners going back to work. But without a revolutionary leadership to provide any wider perspective or strategy, the heroic miners were isolated, starved, and defeated.

On the basis of capitalism – which cares only about profit, not about the livelihoods of workers – the pits were never going to remain open and receive the investment they needed.

But with a communist leadership – one which put forward the need to overthrow capitalism and put industry in the hands of the working class – the miners could have been victorious.

Today, we have comparable disasters taking place: the jobs massacre at Port Talbot, where the steelworks are facing imminent closure; or the gutting and privatisation of the NHS.

This decimation of our industry and public services, if left unchallenged, will have disastrous consequences on workers and communities for generations to come.

The crushing of the miners was the firing shot in an onslaught against the workers’ movement by the capitalist class.

Alongside similar defeats across Europe and in the United States, and a prolonged upswing of world capitalism, this heralded an almost 40-year ebb in the class struggle worldwide.

This was a period of semi-reaction: one of counter-reforms and attacks; of retreat by the labour movement; and of demoralisation and confusion on the left.

But that period is now well and truly over. Workers and youth in Britain and beyond are on the move again, and are beginning to feel their strength.

Throughout all these events and struggles to come, the Revolutionary Communist Party will be active, putting forward the need for a fundamental change in society.

For the last four decades, capitalism has had nothing to offer the ex-mining communities that its profit-hungry policies have ravaged. This system is at a dead-end. We need a revolution.

This will not come easily. We have to fight for it. But we are confident in the future, and are up to the historic task facing us.

As Maureen James states, echoing the feelings of many participants of the Great Miners’ Strike: “It was the hardest year of our lives – but it was the best year.”