Most of the world’s women today are very far from achieving equality, let alone liberation. The wage gap between men and women is one thing, but inequality and oppression are about so much more than that.

From the fear of leaving our drinks unattended when we are on a night out; to the anxiety of walking home alone, having to put up with constant sexist comments and stares; to doing the majority of housework; to doctors not taking ‘women’s diseases’ seriously, and generally being treated as of lesser worth – the list goes on and on…

Inequality and oppression are so ingrained in society’s structures that they permeate a woman’s entire life, regardless of where in the world she lives. They take on their own disgusting expression under capitalism. But they have been passed down through thousands of years of class society.

The alleged solutions we are offered by politicians and the tops of society are anything but satisfactory. They are imbued with an individualistic perspective that rejects class struggle and system change, in favour of promoting a ‘girlboss’ ideology, where sexism and oppression are presented as something that can be overcome by individuals within the framework of capitalism.

But the greatest advances for women’s liberation have not come through independent enlightenment or individual struggles against a systemic evil. They have come through collective, revolutionary struggle to fundamentally change society.

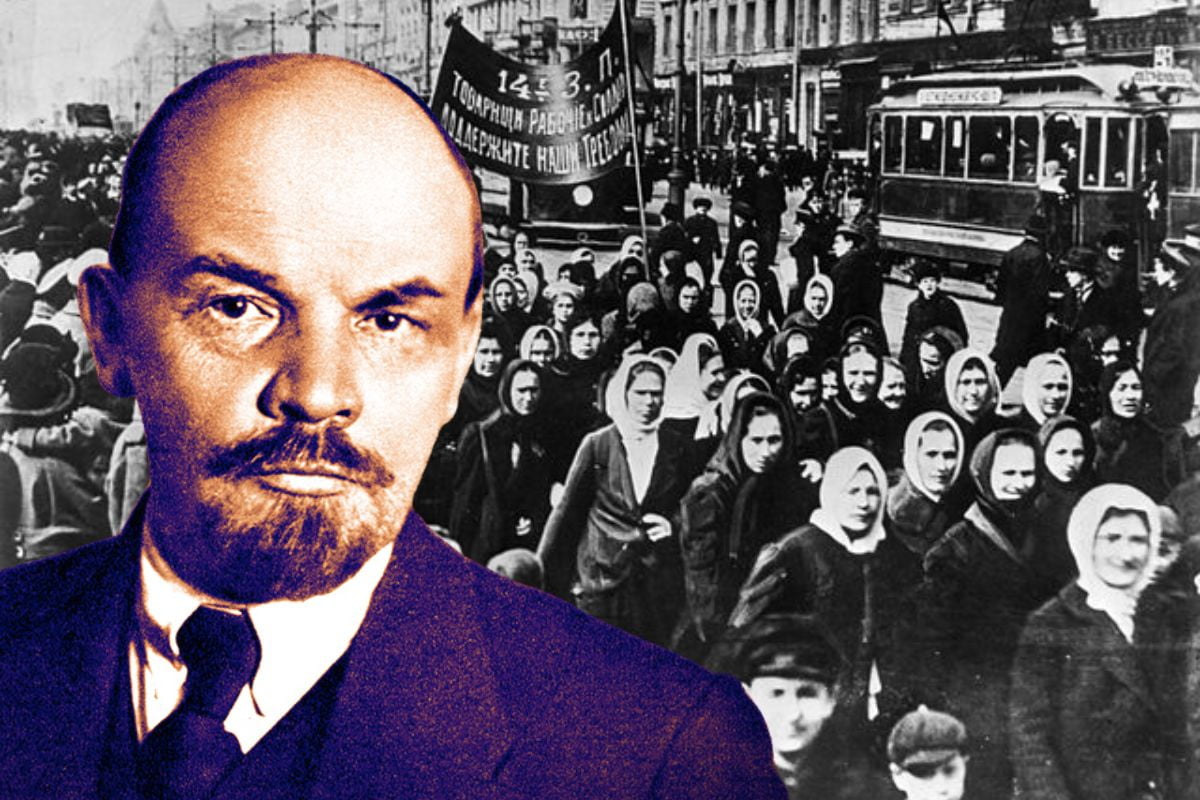

It would therefore be difficult to name another person who has had a greater impact on women’s liberation than Lenin.

This claim will probably make quite a few feminists cringe. What does a ‘dead white Russian man’ have to say about the fight for women’s liberation today?

But the Russian Revolution, led by Lenin, showed that it is possible to do away with the capitalist system that we live under, and to begin building a society without inequality and oppression.

Finally, real women’s liberation was on the agenda. It was not just left up to the individual, however, but was part of a collective struggle of all oppressed layers of society.

Russia before 1917 was a society with an extremely oppressive patriarchal culture. The October Revolution was an earthquake that shook the very foundations of that culture. In one fell swoop, all laws that placed women in an inferior position to men were removed, and homosexuality was decriminalised. That was just the beginning.

The 100th anniversary of Lenin’s death has naturally been met with a smear campaign on the part of the capitalist press. But Lenin is also written off by many feminists who, on paper, claim to be progressive.

They write off Lenin, along with Marx and Engels, as ‘old white men’. But those who jump on that bandwagon are, in reality, politically assisting the ruling class.

They write off the revolutionary idea that, to do away with the oppression of women, you have to do away with class society. And that serves only the richest – those whose power and privilege depend on oppression and inequality as a built-in part of their system.

The women’s struggle and the revolution

Lenin’s entire political struggle was directed towards one goal: the revolutionary overthrow of class society and the construction of an entirely new society, without inequality and oppression: a communist society.

The reason the capitalist class has such extreme hate for this man is that he led the only successful workers’ revolution in world history: a revolution where the working class took power, and which showed that it is possible to organise society in accordance with people’s needs rather than profit.

The Russian Revolution went further than any other event in human history in freeing women from the slavery of class society. The Bolsheviks took giant steps towards real women’s emancipation, sending shockwaves through the world, shaking those in power to their core, and inspiring working women (and men) globally.

It is no coincidence, therefore, that women in many parts of the world received the right to vote (along with many other rights) in the years immediately following the revolution.

The Russian Revolution remains the most important contribution to the fight against women’s oppression in world history. More than 100 years on, the measures that Lenin – and the rest of the Bolshevik Party – took after the revolution remain the most progressive in world history.

The Bolsheviks removed all laws enforcing inequality between the sexes. Women were given the right to abortion and divorce, and the distinction between children born in or out of wedlock was abolished. In comparison, the right to divorce was only introduced in Denmark in 1925, and the right to abortion in 1973!

Danish schoolchildren are taught that the social democrat Nina Bang was the world’s first female minister. She didn’t become a minister until 1924, however, seven years after Alexandra Kollontai was appointed People’s Commissar (i.e. Minister) in the Soviet Union.

One of Kollontai’s first decrees dealt with maternity. This introduced, among other things, 16 weeks of paid maternity leave, and restricted the working week of breastfeeding women to just four days.

Again, one must remember that at that time, maternity leave was utterly non-existent in most of the world. In Denmark, a law on maternity leave to include all female wage workers was only introduced in 1960. And that was only for 14 weeks, and not with full pay, but at the level of unemployment benefits.

16 weeks of paid maternity leave, to this day, exceeds the amount women are entitled to even in the world’s richest country, the USA, where women are entitled to just 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave.

But equality before the law was just the first step taken by the Bolsheviks. This is just the formal prerequisite for eradicating inequality. In order to achieve real equality, it is not enough to have new laws written down on paper. It requires radical changes in the social and economic conditions of society.

Here is where the real work of the Bolsheviks began for the emancipation of women: the work of altering the material conditions, doing away with the root of inequality, namely, class division.

This transformation required an end to the private ownership of the means of production, i.e. the capitalists’ and landlords’ ownership of factories, businesses and the land. In its place, they began constructing a democratic plan of production directed towards solving the social needs of the great majority, the working class, and the poorest farmers.

After the first step of equality before the law had been achieved, Lenin described the next tasks:

“The second and most important step is the abolition of the private ownership of land and the factories. This and this alone opens up the way towards a complete and actual emancipation of woman; her liberation from ‘household bondage’ through transition from petty individual housekeeping to large-scale socialised domestic services.

“This transition is a difficult one, because it involves the remoulding of the most deep-rooted, inveterate, hidebound and rigid ‘order’ (indecency and barbarity would be nearer the truth). But the transition has been started, the thing has been set in motion, we have taken the new path.” (Lenin, International Working Women’s Day, 1921)

If women were to be free, it required an end to housework, which, in Lenin’s words, keeps women in “domestic slavery”. Housework had to be socialised. Concretely, this meant the creation of nurseries, kindergartens, community kitchens, public laundries, etc., etc.

Women have – since the rise of class society, that is, for thousands of years – been chained to the home. Capitalism has played an important role in pulling women out into broader society as workers, and thus as participants in the class struggle. But it has failed to eliminate women’s domestic slavery, which means that working women under capitalism suffer a double burden: both as workers and as women.

Even in developed capitalist countries, the majority of housework falls on women. Today in Denmark, where women’s employment share is almost the same as men’s, women do an average of one hour more housework per day than men.

When children are born, it has a significant impact on women’s salaries, pensions and, not least, time for things other than the family, such as involvement in culture or participation in political activity.

Limited by the material conditions

The ambitions of the Bolsheviks, however, could not go beyond the material reality of the Soviet Republic.

Lenin had made it clear from day one that the revolution needed to spread to the more developed capitalist countries if socialism was to be built.

Unfortunately, the Russian Revolution remained isolated. And in the first years after 1917, the young Soviet state was struggling to survive through the civil war that the most powerful capitalist states had fomented in Russia and to avert famine.

Resources were extremely limited, and thus also the possibility of realising the plans to socialise housework. Seen in this context, that the Soviet state achieved anything at all was impressive. But with Stalin’s dictatorial takeover, a large part of the progress women had achieved after the revolution was rolled back – for instance, in relation to the right to abortion and divorce.

Despite the degeneration and retrogression under Stalin and his successors, the planned economy did bring huge progress for women. Life expectancy for women more than doubled, from 30 years in the Tsar’s time to 74 years in the 1970s. In 1971, there were more than five million kindergarten places, and 49 percent of students in higher education were women. The only other countries where women made up over 40 percent of higher education were Finland, France, Sweden and the USA.

Lenin’s political ideas were based on a materialist philosophical foundation – i.e. the understanding that it is the material conditions that determine consciousness, thoughts, ideology, culture, etc.

The prerequisite for doing away with the sexist and misogynistic culture that for thousands of years has devalued women compared to men, and kept them out of public life, is therefore a change in the material conditions. That means the abolition of the private ownership of the means of production.

But the Bolsheviks didn’t just sit back after they nationalised the economy. They set about extensive work to counter Russia’s chauvinistic culture. Special programmes were launched to eradicate illiteracy among women, and to involve them actively in leading the state and the party.

At the same time, the Bolsheviks did a great job in raising the cultural level in general, thereby doing away with religious prejudices and other forms of chauvinism.

Lenin led a fight for women’s equality not just before the law, but in all areas. That is why we as communists consider ourselves the most consistent champions of women’s emancipation.

In contrast to liberal feminists, Lenin did not stay within the framework of capitalism. The most that can be achieved within this system is equality before the law. And as all of us in Scandinavia can tell you, where equality before the law has long been achieved, this remains a far cry from doing away with the oppression of women.

Liberal feminists have acquired formal equality, and at the same time help to maintain the social and cultural inequality that still predominates.

For Lenin, the focal point of the women’s struggle was class. It is class alone that cuts across all other forms of oppression, and the one around which they all revolve.

The ruling class is a negligible minority in society and does what it can to divide the working class along lines of gender, ethnicity, religion, etc., to try to play off different groups of workers against each other.

Communists and the women’s struggle

As Lenin emphasised, not only is the revolution necessary for women’s liberation, but the participation of women is decisive if we are to have a successful revolution. This is not a secondary question.

It was working women who ignited the Russian Revolution when they went on strike on International Women’s Day in 1917.

Throughout the revolution leading up to October, Lenin insisted again and again on the need to organise women in the struggle. In one of his Letters from Afar – written before his return from exile in 1917 – he wrote:

“If women are not drawn into public service, into the militia, into political life, if women are not torn out of their stupefying house and kitchen environment, it will be impossible to guarantee real freedom, it will be impossible to build even democracy let alone socialism.” (Lenin, Letters from Afar, third letter, ‘Concerning a Proletarian Militia’)

Without the participation of women, the revolution could not win. And the question of organising working-class women in the fight for communism was not only regarded as critical by Lenin in the run-up to the October Revolution, but also afterwards, and in the building of the Third International as a tool for spreading the revolution worldwide.

The oppression of women under capitalism, however, also means that there are generally fewer women than men organised in the struggle. This too was a problem that Lenin tackled:

“Why are there nowhere as many women in the Party as men, not even in Soviet Russia? Why is the number of women in the trade unions so small? These facts give one food for thought. […] We cannot exercise the dictatorship of the proletariat without having millions of women on our side. Nor can we engage in communist construction without them. We must find a way to reach them. We must study and search in order to find this way.

“It is therefore perfectly right for us to put forward demands for the benefit of women. […] The rights and social measures we demand of bourgeois society for women are proof that we understand the position and interests of women and that we will take note of them under the proletarian dictatorship. Naturally, not as soporific and patronising reformists. No, by no means. But as revolutionaries who call upon the women to take a hand as equals in the reconstruction of the economy and of the ideological superstructure.” (Clara Zetkin, Lenin on the Women’s Question)

Lenin repeatedly stressed that the fight for working women’s liberation cannot be separated from the fight for socialist revolution. Inequality and oppression cannot be ended without ending class society. However, that does not mean that he therefore rejected the fight for women’s demands before the revolution.

Communists are sometimes wrongly accused of neglecting the women’s struggle as something that will be solved by the revolution. But that is clearly not true. It is correct that we think revolution is the only way to end women’s oppression, but that does not mean we reject the fight for democratic demands here and now.

We communists do not sit down and wait for the revolution, but throw ourselves into the daily struggle. As Lenin explained, workers can be mobilised through the daily struggle for reforms and democratic demands. And through this struggle, the limitations of capitalist democracy become clear.

The task of the communists is to use the daily struggles to raise the need to fight for a revolution. Lenin explained that the more free and democratic a society is, the more it becomes obvious that the problem is not merely this or that law, but capitalism itself:

“In most cases the right to divorce is not exercised under capitalism, because the oppressed sex is crushed economically; because, no matter how democratic the state may be, the woman remains a ‘domestic slave’ under capitalism, a slave of the bedroom, nursery and kitchen. […]

“Only those who are totally incapable of thinking, or those who are entirely unfamiliar with Marxism, will conclude that, therefore, a republic is of no use, that freedom of divorce is of no use, that democracy is of no use, that self-determination of nations is of no use!

“Marxists know that democracy does not abolish class oppression, but only makes the class struggle clearer, broader, more open and sharper; and this is what we want.

“The more complete freedom of divorce is, the clearer will it be to the woman that the source of her ‘domestic slavery’ is not the lack of rights, but capitalism. The more democratic the system of government is, the clearer it will be to the workers that the root of the evil is not the lack of rights, but capitalism. […] And so on.” (Lenin, from A Caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism)

The more comprehensive the democracy, the clearer it becomes that it is not merely the lack of democracy that is to blame for oppression, but that oppression is rooted much deeper: in capitalism and the very structures of class society.

As mentioned earlier, women’s oppression has far from disappeared from countries in Scandinavia, despite equal democratic rights for men and women.

It is becoming clearer to more and more women that the solution to sexism, violence against women, and their status as second-class citizens does not lie in parliament, but in a deeper overhaul of the structure of society.

Our task as communists is to throw ourselves into these daily women’s struggles, and at the same time use them to show how they are connected to class oppression and the need to fight capitalism.

Lenin was clear that this vital work, of drawing class-conscious women into the revolutionary movement, was not just the job of women. He was against a separate communist women’s movement. It was the job of the whole party.

It was necessary to educate and draw in all communists on the question of women’s oppression and the importance of revolutionary work among women, including male comrades, if the work was to be conducted at all successfully.

That even sometimes meant overcoming the resistance of male comrades, as the German Marxist Clara Zetkin recalled Lenin saying:

“They regard agitation and propaganda among women and the task of rousing and revolutionising them as of secondary importance, as the job of just the women-communists. None but the latter are rebuked because the matter does not move ahead more quickly and strongly. This is wrong, fundamentally wrong! It is outright separatism. It is equality of women à rebours, as the French say, i.e., equality reversed. […]

“Very few husbands, not even the proletarians, think of how much they could lighten the burdens and worries of their wives, or relieve them entirely, if they lent a hand in this ‘women’s work’. But no, that would go against the ‘privilege and dignity of the husband’. He demands that he have rest and comfort. The domestic life of the woman is a daily sacrifice of self to a thousand insignificant trifles. The ancient rights of her husband, her lord and master, survive unnoticed. Objectively, his slave takes her revenge. Also in concealed form. Her backwardness and her lack of understanding for her husband’s revolutionary ideals act as a drag on his fighting spirit, on his determination to fight. They are like tiny worms, gnawing and undermining imperceptibly, slowly but surely.

“I know the life of the workers, and not only from books. Our communist work among the masses of women, and our political work in general, involves considerable educational work among the men. We must root out the old slave-owner’s point of view, both in the party and among the masses. That is one of our political tasks, a task just as urgently necessary as the formation of a staff composed of comrades, men and women, with thorough theoretical and practical training for party work among working women.” (Clara Zetkin, Lenin on the Women’s Question)

The women’s struggle and communism

Capitalism is in a deep crisis. It is not just an economic crisis, but a historical crisis permeating every pore of society. Everywhere you look, the world seems to be descending into wars and climate disasters. Sexism, racism, transphobia and other forms of discrimination and oppression are rampant.

This crisis is felt particularly acutely among young people, who experience it in all areas of life. It means a deterioration of culture, human relationships, and our psyche, as we see with the mental health crisis.

The only thing young people and workers are offered is abysmal pessimism and individual solutions. But the crisis of capitalism isn’t just leading to pessimism.

The dead end of the system is causing a qualitative shift in consciousness among more and more people who are unsatisfied with individual solutions. They are looking for ideas that can provide a way out of this crisis. Millions of women and men worldwide are mobilising in the fight against inequality and oppression.

The alternative to pessimism and individual solutions is to be found in Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Their response was a collective fight against the entire system. They did not stop within the framework of capitalism. They uprooted the very cause of oppression and inequality.

This is the tradition we communists build on today. We throw ourselves into the women’s struggle – but armed with the clear perspective that it cannot be separated from the struggle for communism, and that anyone who wants to fight seriously against the oppression of women must organise themselves in the struggle for communism.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks began the struggle. It is up to us to complete it once and for all, and create a society where women and men can live a human existence, without inequality and oppression.