How often have we been told that capitalism is the most ‘rational’ social system? That its very existence is its own justification?

The bourgeoisie repeats Hegel’s dictum, “all that is real is rational” – i.e. whatever exists must do so for a reason, and so is unavoidable.

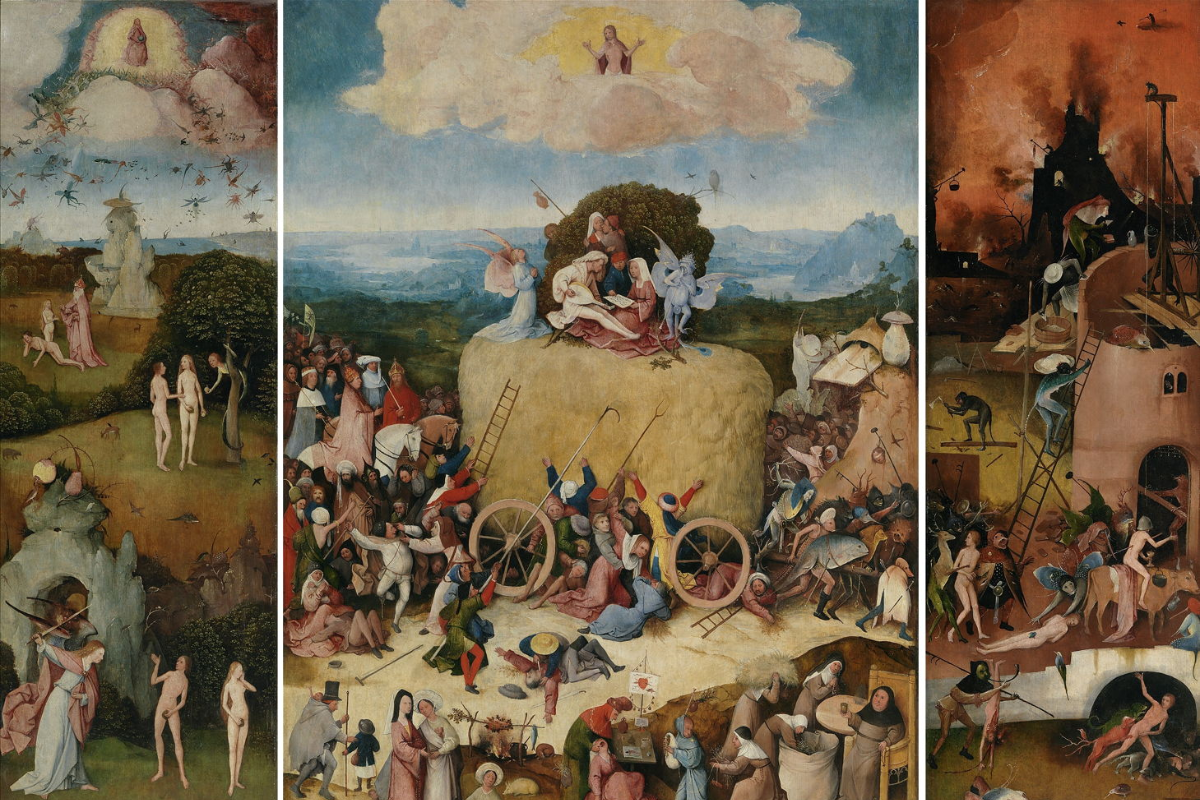

Yet capitalism itself is not eternal. It arose out of the transformation of feudalism: a mode of production defined by nobility, localism, serfdom, and perpetual warfare.

But feudal society contained within itself the seeds of its own destruction: the slow, uneven emergence of bourgeois economic relations, which increasingly came into conflict with the old order.

From the thirteenth century onward, these tremors grew more frequent, culminating in open struggle against feudality, and eventually in revolution.

Feudalism did not collapse under the weight of its contradictions alone; no ruling class in history surrenders without resistance. But as the economic foundation shifted, political revolutions delivered the final blows, clearing the way for capitalism.

In fact, when scrutinised dialectically, Hegel’s formula reveals the opposite: All that exists deserves to perish.

And just as feudalism perished, so too will capitalism.

No land without lord

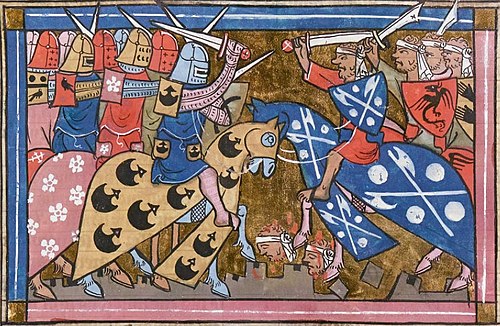

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century, European society descended into widespread instability and warfare.

At first glance, feudalism appeared to offer stability. Local warlords, promising protection from pillaging and raids, elevated themselves above the rest of society and formed a new ruling class, basing their power on the seizure and control of land.

As a folk saying put it: “No lord without land, no land without lord.” Society and civilisation were seen as guaranteed only through the existence of this landed aristocracy, which justified its dominance with quasi-religious claims.

The manor was the basic unit of feudal society. It was the centre of economic and social life, structuring the class relationship between lord and serf (from servus, Latin for slave). Around 90 percent of the population of England, for example, lived and worked in the countryside.

The vast majority were peasants; both free and unfree, though mostly unfree. Trotsky once described the peasantry as the “pack animal of civilisation.” In practice, peasants were valued far less: in eleventh-century France, one peasant was reckoned to be worth only a third of a horse.

Villeins (unfree peasants) were bound by custom to the lord’s manor, and could not leave the land without permission.

The lord’s ownership of the land was reinforced through numerous customary fines and dues paid mainly in kind or, rarely, in cash: a merchet when a tenant’s daughter married; a leyrwite for any of their children born out of wedlock; a heriot – the best beast – when a tenant died; and an additional fine for the tenants heir to take up their inheritance.

The manor was largely self-sufficient, with its own mill, bakery, wine-press, woodlands, blacksmith, and more. Peasants held small plots for subsistence farming, producing food, wool, and timber, while also performing labour services for the lord.

Rent was paid both in kind and in labour, usually two to three days a week on the lord’s demesne, the land the lord kept for his own use rather than leasing to tenants, with extra work demanded on ‘boon’ days.

The lord’s demesne always came first: his fields had to be ploughed, sown, and harvested before those of the peasants. If storms threatened or repairs were needed to roads or bridges, peasants were compelled to abandon their own plots to serve the manor. As another saying went:

“If he have fat goose or hen,

Cake of white flour in his bin,

’Tis the lord who all must win.”

Most peasants did not earn wages. Their obligations were customary rather than contractual: the peasants gave their labour and surplus from the land. In return, peasants received small plots to sustain their families and protection.

The Church was the greatest landowner of all. Bishops and monasteries managed vast estates, sometimes more efficiently than secular lords. Priests were forbidden to marry partly to prevent church lands from being divided among heirs, enabling the church to expand its holdings through both inheritance and tithes: payments of produce such as wool or geese, often enforced through fear of damnation.

As Engels observed, the Latin Church was the “great international centre of feudalism”. The Church provided the spiritual and ideological justification for the system, while the nobility supplied its military defence.

Feudalism was characterised by slow progress in the productive forces. This is because any surplus was consumed directly on the manor; money played little-to-no role.

Markets existed only at the margins of manorial life, strictly regulated by lords and bishops. Roads were poor, banditry was common, and traders faced tolls from every lord whose lands they crossed. Odo of Tours astonished contemporaries when, in the eleventh century, he built a bridge across the Loire and allowed free passage without tolls.

Nevertheless, within these economic and social relations laid the seeds of a new order: the beginnings of bourgeois property relations.

Rise of towns and commerce

Gradually, the amount of commodities – goods produced for the market, instead of for consumption by the producer or their lord – grew. As a result, the need for money grew, as did a place to conduct trade. This marked the rising prominence of towns and the emergence of a new social order.

As always, what underpinned this evolution towards money, commerce, and towns was a development of the means of production.

An agricultural revolution took place in Western Europe in the eighth century (around three hundred years after feudalism emerged). This led to a newfound surplus and a population boom. The population of England doubled in the space of a century.

As a result, many hours and hands were made available for the production of a variety of other products in a more systematic way. In short, agricultural productivity and surplus facilitated the division of labour and increased specialisation in the crafts. Trade, and thus money, made a very gradual return. Viking invasions and other plagues led to regular setbacks in this process, however.

By the eleventh century, commerce had expanded significantly. The wool trade in England, for example, fuelled both domestic and foreign exchange, as English wool was exported to weavers in Flanders and the low countries.

In response to this growing trade, and spotting an opportunity to fund constant warring with France, the English crown imposed taxes on wool exports. The military campaigns these financed ultimately weakened the social and economic foundations of feudalism itself.

The Crusades, for example, provided further impetus to trade. Pilgrimage routes doubled as trade routes, attracting both the pious and those motivated by wealth, land, or repayment of debts.

The Church expanded its influence; nobles and knights sought profit; and trading city-states – particularly Venice, with its ideal location for Mediterranean commerce – flourished most of all.

Merchants spread across Europe, stimulating demand for foreign goods. Trade routes, once dominated by Islamic empires, connected East and West for the first time since the fifth century.

As commodities penetrated domestic markets, capitalist relations began to develop. New towns emerged near castles, monasteries, and crossroads, while lords shifted from relying solely on serf labour to fulfil their needs to purchasing goods from skilled town craftsmen.

Markets and trade fairs now dealt in commodities from across the globe, rather than just local produce. At their centre stood money changers – early bankers, who served nobles, kings, and townspeople alike. Through money, the bourgeoisie established growing social, and at times even political, ascendancy over feudal lords.

With commerce expanding, money became more attractive and versatile as a medium of exchange, undermining the natural economy of the self-sufficient manor and transforming it into a money economy. Lords themselves encouraged markets to increase tax revenue. But in doing, so they eroded the very foundations of their class power.

Serfdom abolished

The emergence of free labour gave a powerful boost to commodity production. Central to this was the Black Death, which struck Western Europe in the mid-fourteenth century, killing roughly a third of the population.

With so many labourers dead, lords struggled to find workers for their estates. Rents fell sharply, reducing manorial income by as much as 20 percent. For peasants who survived, the burden of labour increased.

At the same time, lords were forced to hire wage workers to replace lost serf labour. By 1349, the scarcity of labour for hire meant that wages on many estates had doubled. Peasants even enjoyed meat pies and ale on their lunch breaks!

Under these conditions, serfdom became untenable. Labourers could seek out better employers, and lords had to compete for their service by paying money wages.

As peasants increasingly paid rent in cash, rather than labour or goods, the relationship between landowner and worker shifted from master-serf to landlord-tenant. The very social foundation of feudalism was eroding.

The ruling class responded by trying to suppress wages and reassert control. The Statute of Labourers and the Poll Tax sought to cap earnings and impose financial burdens on peasants. The Church also joined the effort, issuing edicts against labourers who demanded higher pay.

Some lords imposed new restrictions. The Abbot of Evesham charged heavy fees for employing his villeins, while others fined tenants for working under different masters. Customary obligations such as the merchet and leywrite were exploited with renewed vigor.

Tensions between the peasants and the lords erupted during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. A section of the peasants from south-east England marched on London, executed the Archbishop of Canterbury, and forced King Richard II to accept demands such as the abolition of serfdom, cheaper land, and free trade.

Although Richard II later betrayed the rebels and brutally repressed the movement, the old order could not be restored. Serfdom never fully returned. The rise of free labour permanently weakened the foundations of feudalism. Villein status, though never formally abolished, faded into obscurity.

‘Without serf, who is the lord?’

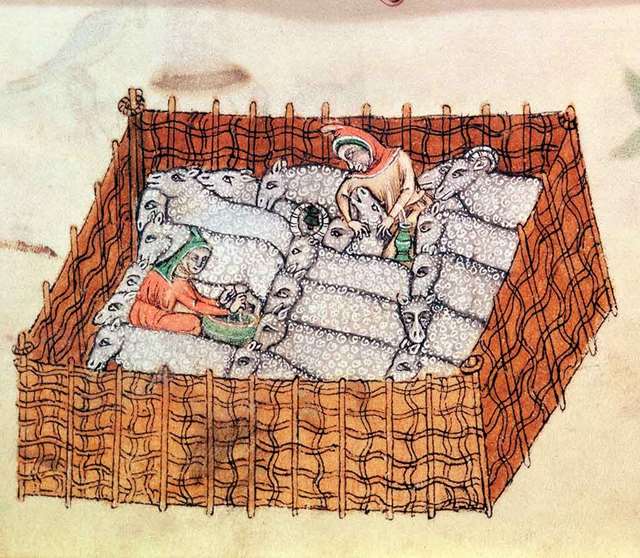

Some lords began to consolidate vacant tenancies into large landholdings, in order to cultivate cash crops for exchange.

Seeking greater monetary gain to satisfy their material desires, lords expelled increasing numbers of remaining tenants from their land to facilitate the spread of sheep farming. Their fields were converted into pastures, worked by wage labourers, supplying wool for the growing market. This process was part of the primitive accumulation of capital.

This transformation enriched the emerging capitalist farmers, while simultaneously creating a landless peasantry, compelled to sell their labour power.

Instead of tending small flocks for subsistence, nobles now managed vast herds. The Abbot of Peterborough oversaw 16,300 sheep; St. Swithun’s church in Winchester 20,000; and the Earl of Lincoln 13,000 across his estates.

Wool became so valuable it was said to represent “almost half the wealth of the whole land.”.

At the same time, in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, some lords abandoned direct cultivation of their demesnes, renting them out on long leases. The landlord’s role shifted from cultivator to rentier, and the exchange of labour became more universal.

Freed from feudal obligations, yeomen (freeholders) took over these lands – paying low rents, and establishing themselves as independent small farmers with a few hired hands. Over time, land ownership became increasingly concentrated into fewer hands, oriented toward commodity production.

As Engels observed:

“While the chaotic battles among the dominant feudal nobility were filling the Middle Ages with sound and fury, the quiet labours of the oppressed classes all over Western Europe were undermining the feudal system and creating a state of affairs in which there was less and less room for the feudal lords.”

Exhausted dynasties, bankrupted by endless wars, were replaced by new landlords more concerned with profit than chivalry – eager to reap windfalls from these endless conflicts, or lease their lands to capitalist farmers or become capitalists themselves.

This process, however, required new stimulus. The search for gold and silver drove the discovery of the Americas. Though initially led by feudal monarchs and aristocrats, such ventures ultimately strengthened the development of commodity production, as raw materials from the New World would come to be transformed in the town’s manufactures into commodities for sale.

Merchants organised for mutual protection and economic leverage – sometimes cooperating with feudal authorities, sometimes openly challenging them. This emergent bourgeoisie of the towns longed for freedom of movement of capital and labour.

But this freedom clashed with the rigid structures of feudalism. Lords treated towns like extensions of their manorial estates, imposing dues and feudal justice. Yet the dynamism of trade resisted such fixed controls.

Gradually, the economic base of society shifted. Bourgeois relations developed within feudalism. But their full realisation required political revolution.

The judgment rendered by money

By the end of the Middle Ages, bourgeois relations of production were well developed. Yet political and social institutions still reflected feudal structures. This contradiction gave rise to an era of upheaval, where a new society struggled to emerge from the womb of the old.

As Engels aptly describes, in the final instance it was “gunpowder [which was] the executor of the judgment rendered by money”.

Gunpowder breached the walls of feudal castles, signaling the decline of the nobility’s military dominance. This was not a single, conscious act of revolution, however, but a long, uneven process.

Politically, the bourgeoisie remained weak. Even as feudal society decayed, townsmen could not yet rule beyond their city walls, let alone command entire nations.

The bourgeoisie, therefore, could not yet assert itself as the ruling class of a nation. Its struggle against feudalism unfolded across centuries, culminating in three decisive turning points: the Protestant Reformation, Absolutism, and the English and French Revolutions.

Each stage advanced more consciously than the last, stripping away the remnants of feudal society.

The Protestant Reformation cloaked political conflicts in religious language. Luther’s 95 theses inspired the revolt of lesser nobles under Franz von Sickingen (1523) and the great Peasants’ War (1525).

While both were ultimately defeated, the Reformation permanently shifted authority from Rome to monarchs.

The Tudor monarchy in England – especially under Henry VII and Henry VIII – curbed the power of the old nobility and of the Church in Rome. Under the guise of religious reform, they redistributed aristocratic and church lands to a politically loyal gentry.

This created a new class of landowners driven solely by profit. By the seventeenth century, segments of the aristocracy had allied with the financial and industrial bourgeoisie, ensuring the state increasingly served capitalist expansion.

But even these gains could not do away with the old feudal aristocracy. Tensions erupted in the English Civil War, where under religious guises the bourgeois and the petty bourgeois triumphed against the idle aristocracy.

The monarchy was overthrown, the House of Lords abolished, and the Commonwealth established. Under Cromwell, feudal barriers were swept aside: royal monopolies dissolved; royalist and Church lands expropriated; Ireland subjugated for economic exploitation; and merchant capital set free.

But the industrial and commercial bourgeoisie had not yet fully displaced the landed aristocracy from political rule, when a new competitor – the working class – entered the stage of history.

From bourgeois revolution to counter-revolution

With the conquest of political power came the brutal era of primitive accumulation: slavery, colonial plunder, and land enclosures. As Marx wrote in Capital: “Europe had lost the last remnant of shame and conscience.”

The new ruling class – the bourgeoisie – required protection in law; hence the sanctity of the ‘rule of law’, and equality in the eyes of the law for owners of property under capitalism. This legal recognition gave the bourgeoisie the confidence to invest further and expand accumulation.

What defined the new capitalist epoch was the undisputed dominance of capitalist property relations, commodity production, and an unprecedented development of the productive forces.

Unlike the long, protracted decline of feudalism, the bourgeois epoch has unfolded – and now declines – at a much faster pace.

Today, capitalism itself has changed. It is no longer the industrial capitalism of its youth, but has matured into imperialism: a stage characterised by finance capital, overproduction, and the desperate global export of capital, to stave off crisis within individual capitalist nations.

Ironically, the capitalists today resemble the old nobility: an idle class, clinging to inherited positions of privilege; increasingly reluctant to invest in new productive forces. Instead, they have begun reversing globalisation and dismantling the very system of world trade they once championed.

From the beginning, this system contained contradictions – namely, that capital cannot exist without wage labour.

As soon as wage labour appears, production is socialised: work becomes collective; divided among many. But the fruits of this social labour remain privately appropriated by a tiny class of capitalists. This contradiction cannot be resolved by gradual reform or an organic ‘evolution’ into socialism.

Just as the bourgeois order arose through violent upheaval, so too must socialist property relations be established through political revolution – seizing the immense productive forces brought forth by capitalist relations by a new ruling class: the workers.

The hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie lies in its denial of this reality. Though its own rule was born in revolution, it falsifies history – preaching gradualism and reformism to delay its downfall.

Yet the working class, with conscious leadership, faces the same historic choice Marx posed: either the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or the common ruin of the contending classes.