This pamphlet [available from Wellred Books], written by Engels in 1876, represents an extremely significant contribution for Marxists to study. At first glance this may seem surprising. It is an unfinished essay on human evolution, which might seem quite remote from the pressing economic and political questions of our time. Its author was not a biologist, and the state of knowledge on this topic in 1876 was extremely limited. What then, can this little work offer to the working class movement in the present period?

First of all, the unfinished nature of the work should not bother us. Some of the most insightful and clarifying of all Marx and Engels’ writings were never published. The German Ideology for example, is amongst the most frequently quoted of their works, and this is because it captures, in elegant brevity, many key insights into their philosophical outlook, and their view of human history, i.e. dialectical and historical materialism. If your aim is to deepen your understanding of Marxist philosophy, and learn to apply it, The Part Played by Labour is extremely valuable to study.

In a few pages Engels proves that a conscious dialectical and consistent materialist approach can allow us to make powerful scientific predictions. In fact, Engels’ theory of human evolution was far in advance of the academy at the time, outclassing even the insights of Darwin on the question.

“Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us.” – F. Engels pic.twitter.com/JfiuIzedwr

— Wellred Books Britain (@WellredBritain) June 23, 2023

The essence of Marxism is to derive theories from past experience and then use these to draw out laws, by which we can understand development, and predict events to a certain level of accuracy. This means that it is a scientific approach to society. Without retaining this scientific approach, Marxism would lose its power. Revolutionaries cannot hope to liberate our species without an understanding of the laws that govern history. Without this, we cannot draw any of the conclusions necessary to build an effective strategy.

With regards to the specific content of this work, understanding why human history has unfolded as it has, and being able to outline the potential of our species and how it might be unleashed, is a significant task. It requires us to understand the relationship between human society as a whole, and its constituent parts, the individuals that make it up. Here Engels deals explicitly with this question. He uncovers the essential secret of all human social development, the thing which drives our species forward, and sets it apart from all others: labour.

Labour can be defined as the ability to consciously transform our environment to achieve our own ends, especially by using tools. But this abstraction is insufficient. Many animals are capable of transforming their environments, from birds and their nests, to beavers and their river dams, to Chimpanzees who make tools for hunting and termite fishing. All these animals not only transform the world around them, but to some degree they know why they are doing it. In other words, all animals have some capacity to think logically and to plan, and can produce things according to their plans.

What distinguishes humans then, is not only our planned production, but several special features of the planning. First of all, our labour is not merely individual, but social. We collaborate, and we do so far better than any other animal, principally because of our superior mode of communication: language. Beyond this, our methods of labour, the productive forces we have at our disposal, do not disappear with the death of each individual. They are transmitted to future generations who improve upon the earlier methods. As Engels put it:

“By the combined functioning of hand, speech organs and brain, not only in each individual but also in society, men became capable of executing more and more complicated operations, and were able to set themselves and achieve, higher and higher aims. The work of each generation itself became different, more perfect and more diversified.”

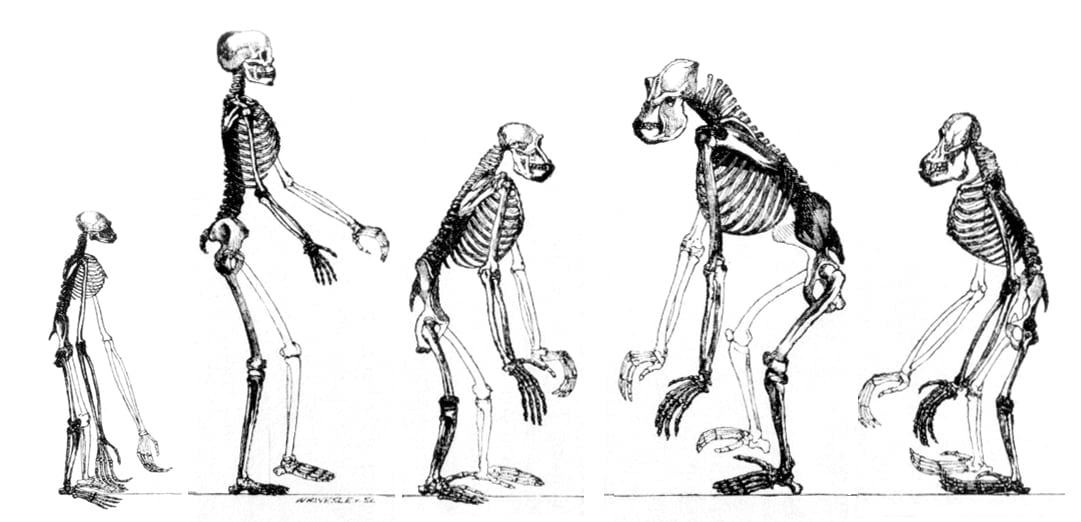

Thus, humans are separated from the animal kingdom, says Engels, by our need to transform our environment in order to live, which we do cooperatively, using methods which accumulate through time. Our ability to develop the productive forces to consistently extract more resources from the world around us and gain more control over the conditions of our existence, is what has allowed humanity to move beyond the realms of simple biological evolution, to social evolution. While biological evolution requires thousands, even millions of years before we see significant changes, human societies change and develop at a relatively breakneck pace due to this capacity.

How is it that humans, alone, were able to develop this unique capacity? Our earliest ancestors, the apes which lived in the forests of Africa, could not do this. They had neither the manual dexterity nor the cognitive ability to manufacture a simple symmetrical hand-axe, let alone to plan a factory, erect a cathedral or design an iPhone. This, in itself, was the product of a long period of biological evolution, which Engels addresses in this pamphlet.

“The decisive step”: bipedalism

Engels begins his analysis with a simple set of premises: labour is the source of all wealth; nature supplies the raw materials for labour; human kind can only exist as long as it labours. This means that our evolution must have driven us to the point where we could perform labour, but more importantly, the ability to perform labour, once firmly established in our lineage, set the direction of future adaptations.

Engels traces this story back many hundreds of thousands of years to what he describes as an ape species covered in hair with pointy ears that lived on a now sunken continent called Lemuria. We now know that all human species, including Homo sapiens, have their origins in Africa, but Engels lacked the archaeological data to have known otherwise.

Engels suggested that this ape ancestor was a tree dweller and was probably already a fairly social animal living in “bands”. He argued that the feet had different functions to the hands owing to their reliance on climbing and that this led them to ‘lose’ the habit of using hands to walk and the development of a more upright posture. According to him, this was the origin of bipedalism.

Bipedalism, he called the decisive step in the transition from ape to man because this freed the hands of locomotive tasks. From then onwards the hands could become exclusively focused on laborious activity, especially the manufacture of tools.

Aside from the dating and locating of human origins, it is astonishing just how much of this narrative chimes with the modern evidence. Only in the last 30 years or so have the very earliest Hominins (species more closely related to humans than chimpanzees) been added to the fossil record. The species Ar. ramidus, nicknamed ‘Ardi’, is around 4.4 million years old, making him our oldest hominin ancestor whose skeleton we have been able to digitally reconstruct.

Many of Ardi’s traits are remarkably similar to those that Engels predicted. In particular, Ardi was certainly bipedal on the ground, but he was also an adept tree climber. Of special note is his opposable hallux (big toe) which has been lost in all later hominins. This accurately aligns with Engels description of the Lemurian ape ancestor, whose hands and feet became differentiated over time.

We still do not know exactly how or when our ancestors became committed ‘bipedalists’ but recent evidence suggests that the process is more or less as Engels suggested. What fossils like Ardi show is that our ancestors transitioned to bipedal locomotion long before we began walking on the plains. It is likely that walking on two legs began as an occasional form of movement, much as it is in modern chimps, but over time came to dominate hominin life.

With the emergence of the genus Homo, 2.8 million years ago, the woodlands had finally been transformed into plains, thereby accelerating the dependence on bipedal locomotion. This is why Homo erectus, amongst the earliest species in our genus, was not merely adept at walking on two legs, but could not do otherwise. For this reason Homo erectus is classified as an “obligate biped”, as are we. He had no opposable toes, no upper body muscular attachments to support adept tree climbing, and a suit of pelvic and leg adaptations to support this mode of locomotion.

Hands free, hands full

Once we began to walk on two legs we could focus our hands exclusively on more dextrous activity. For Engels, the most important of these was making and using tools. Of course many great apes use tools in the wild, as do several bird species, most notably crows. But no species has the kind of skill in this domain that humans have. Here the real genius of The Part Played by Labour begins to shine.

What Engels realised was that the evolution of the hand must have occurred according to a logic of its own – a dialectic. The hand would first become more capable of fashioning tools, until a barrier was reached. To develop our tools and their products any further we would have to acquire new traits.

The first of these were greater dexterity, fine motor skills etc. Fossils alone do not give us a clear picture of exactly when or how the hands evolved in response to their new roles. Indeed, we do not even know which Hominins were responsible for the major leaps in our manufacturing capabilities. This is because stone preserves far better than bone and nobody has discovered any fossils alongside stone tools.

New pamphlet from @WellredBritain: ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’.

“This is what my biology degree was missing. Engels’ clarity is proof of the need for dialectical materialism in understanding the development of humanity.” – Harry pic.twitter.com/DXYjgyKwtz

— Socialist Appeal (@socialist_app) May 2, 2023

However, we do know that the more sophisticated stone tools, the bi-faced Acheulean hand axes, which are a dramatic leap beyond the simple Oldowan choppers (barely distinguishable from unworked material) only emerge in the record about 1.75 million years ago, shortly after Homo erectus. This suggests that as we left the trees and truly liberated the hands from locomotive operations we quickly developed our physical and mental capacity for production. Boyd and Silk have this to say about H. erectus and the Acheulean industry:

“It is easy to see how a biface might have evolved from an Oldowan chopper by extending the flaking around the periphery of the tool. However, Acheulean tools are not just Oldowan tools with longer edges; they are designed according to a uniform plan and have regular proportions. The ratio of height to width to thickness is remarkably constant from one hand axe to another. Homo erectus must have started with an irregularly shaped piece of rock and whittled it down by striking flakes from both sides until it had the desired shape. Not all the hand axes would have come out the same if their makers hadn’t shared an idea for the design.”

The above passage bares a striking resemblance with this one from Engels:

“The first operations for which our ancestors gradually learned to adapt their hands during the many thousands of years of transition from ape to man could have been only very simple ones… Before the first flint could be fashioned into a knife by human hands, a period of time probably elapsed in comparison with which the historical period known to us appears insignificant. But the decisive step had been taken, the hand had become free and could henceforth attain ever greater dexterity; the greater flexibility thus acquired was inherited and increased from generation to generation.”

Note also Boyd and Silk’s reference to mathematical precision, planning and premeditation. As Engels remarks later, laborious activity would create powerful selective pressure for the emergence of “increasing clarity of consciousness, power of abstraction and of conclusion”.

The intelligence of modern humans has made us very successful in the Darwinian ‘struggle for survival’. However, it is unique in nature. Engels realised that the modern human brain could only start emerging at the point when early humans became dependent on labour to survive. This is because from that point onwards the easiest path to greater ‘fitness’ (the ability to produce more offspring that will survive to reproductive age) would have to be the one that allowed us to improve upon earlier technology.

Believe it or not, this line of thinking, which might seem fairly intuitive, did not achieve mainstream appeal in evolutionary biology until the 1970s, with Cavelli-Sforza and Feldmen’s idea of gene-culture coevolution. The classic example of this is the evolution of lactase persistence, which allows some humans to drink cows milk into adulthood. The gene for this spread through Eurasian and African populations about 7000 years ago following the advent of cattle domestication and their exploitation for secondary products such as milk.

It was proven that once new kinds of production emerge the human genome can adapt to them. What Engels had realised, long in advance of mainstream biology, was that this process was the secret to the emergence of Homo sapiens in the first place. The human body is not only the organ of labour, it is its product. Man made himself.

In the 1870s anthropologists had not lost the habit (many still have not) of assuming that the conquests of humankind came from pure thought, rather than novel thinking arising from human needs. As such, they believed that the brain was the first organ to develop. From its expansion new capabilities were supposed to have emerged.

It would take a century for Engels to be vindicated on this point. The finest example of this was the fruitless search for fossil remains of a ‘big-brained ape’ that had the cognitive capacity to then develop bipedalism and early tool use. In reality, scientists discovered the opposite.

In the 1970s a series of finds demonstrated without a shadow of a doubt that the first obligate bipedal apes preceded the dramatic expansion of the brain by well over a million years. The first of these was Lucy, a 3.2 million year-old Austrolopithicus afarensis skeleton who was extremely ape-like above the neck, with a cranial volume about 3-4 times smaller than modern humans, but whose locomotion was almost identical to our own.

The second crushing blow to the brain-first narrative was the discovery of the 3.7 million year-old Laetoli footprint trail in Arusha, Tanzania, which is a perfectly preserved image of two ancient primates walking upright across an ash landscape, just as we would.

Engels was able to see what others could not because he had the benefit of a conscious dialectical materialist insight. Where the idealists sought the source of all development in the brain, consciousness and the like (why the brain would have suddenly developed without the stimulus of an activity like tool production, they have no satisfactory answer to), the materialist approach has always been to seek the source of development in the material world, in the real activity of individuals and the tasks they were performing each day in order to survive. This is equally as true for our earliest ancestors.

And as for dialectics, in opposition to the ‘empirical’ biologists who sought definitive ‘cause and effect’ for human evolution, Engels understood that the process would be more complex than this. He saw that where labour would begin as the cause of our evolution, it would be negated as such, and become its effect, as new capabilities would drive production forward to more complex heights.

He also understood that the impact of labour was not only upon the hand or the brain, but the entire body. He attributes this to Darwin’s idea of correlated growth, where the evolution of one trait by selection necessarily carries with it the evolution of other traits which are not selected for the same reasons. Stephen J. Gould called these phenomena exaptations and spandrels. We now know that the entire human body has been altered by the evolution of labour practices. For example, the size of our chewing muscles have reduced because cutting and hammering implements allow us to soften our meat before processing it with the molars.

‘Something to say to each other’

Labour created a selective pressure that went beyond the individual. Through its impact on each atom of the population new characteristics arose at the purely social level. These emergent traits were heightened cooperation, and most critically of all, language.

“On the other hand, the development of labour necessarily helped to bring the members of society closer together by increasing cases of mutual support and joint activity, and by making clear the advantage of this joint activity to each individual. In short, men in the making arrived at the point where they had something to say to each other.”

Of course cooperation of sorts exists in other species. However, no other gregarious being needs to cooperate on tasks as complex as those of humans. For this reason, Engels argues, humans developed increasingly complex verbalisations in order to be precise about exact aspects of their work. This would give rise to language.

Of all of Engels’ bold assertions the idea that language is the spawn of labour remains the most controversial. A common alternative explanation for language evolution is that it was simply a useful way to pass on ideas and maintain social bonds. No doubt it is, but evolutionary theorist Joe Henrich has some useful words to say on this score:

“Several of our colleagues are fond of the “Why not baboons?” stratagem: If an evolutionary scenario is meant to explain some unique (or at least nearly unique) feature of humans, then it must also be able to explain why baboons—and many other animals— do not fall under the same evolutionary logic. We have seen many clever theories crumble before this interrogation.” (Henrich et al, 2003)

Why exactly did humans alone develop language? Here we see the limitations of the idealist outlook. To say that language is simply the vessel for the transmission of ideas does not explain why ideas emerged or needed to be transmitted in the first place. Henrich goes on:

“In modern humans, a suite of social learning abilities contributes to the maintenance and accumulation of culture. Simpler forms of observational learning (of physical skills, for example) likely provided a foundation for more complex kinds of social learning and inference, such as those associated with symbolic communication and language.”

In other words, language became necessary first and foremost in order to efficiently teach others how to produce and use items of necessity.

With all due respect to the vegetarians…

Most archaeologists now believe that one of the most important early uses of stone tools was in animal butchery. Many primates eat meat, but humans seem to be especially fond of it when it is available. Like chimps, our ancestors consumed meat raw long before cooking was discovered. However even in the raw state it provides a richer source of protein and nutrients than wild vegetables or other forageable resources. This is important for childhood brain development and optimising adult brain function.

It may be true that in the modern world a vegan diet can be a healthy alternative to animal products, but this was not the case 1 million years ago. Engels believed that meat eating unlocked the “chemical premises for the transition from ape to man”.

The argument is posed in a Lamarckian form, which assumes that traits evolve by passing down phenotypic changes acquired during an individual’s lifetime, rather than by genetic inheritance. In the 1870s nobody really knew about genetics and it would take several decades before the concept was successfully synthesised with Darwinism.

Simply eating meat therefore, could not have driven early human evolution on its own. It would have simply maximised the mental and physical potential that already existed in the DNA. For meat-eating to have a more powerful impact genetic mutations would have had to occur which would force the bodies of individuals to change through the generations in response to meat.

But Engels was essentially right on this point. Meat processing, especially cooking, following the mastery of fire, which probably occurred quite early in the genus Homo, would have created a selective pressure on the genome to reduce the size of the gut. This would have happened to make digestion more efficient, which is possible when the food you eat is already heavily processed.

More efficient food consumption would have saved our ancestors time. Beyond that, it is possible that we evolved to harness the nutrients unlocked by cooking more effectively in brain development.

One feature of meat-eating which Engels did not explore was its social impact. Success in hunting is inevitably more variable than in gathering, and unlike lions or wolves, humans have to spend decades learning how to do it properly as we lack the power, large teeth and claws, or instincts to learn it quickly. Complicating things further, women tend to be at a comparative disadvantage as hunters because they have to spend more time feeding their infants. In order for a primate to benefit from eating large quantities of meat therefore, the ability to share the meat, and knowledge of how to hunt it, across the group is essential.

Thus the increased reliance on hunting created an impulse to produce according to ability, and receive according to need in the early hunter gatherer bands. This communistic tendency remains almost universal in modern foraging communities; it is a major difference between the economic life of the chimp and the early human.

Society and social evolution

With cooperation, language and the meat diet, the most basic building blocks of human society were now in place. But as we know human development did not end here, in fact, this was only the beginning.

Engels makes the point that technology and technique develop from one generation to the next, such that no single individual or society develops new kinds of technology or culture from scratch. Instead, innovations accumulate through time, so that each generation actually depends on expertise which they did not acquire themselves.

On this basis the whole human history proper, the kind which Marx and Engels discuss in The Communist Manifesto and The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, developed. From hunting and gathering to animal and plant domestication, to urban settlement, the state, empires, international markets, the modern world.

For Engels, the final distinction between humanity and the rest of the animal world was that, where the beasts only alter their surroundings by accident, or by extremely limited modes of planning, humanity masters nature, “makes it serve his needs”. In other words, humans are capable of turning the laws of Darwinism on their head. All other species evolve only because of environmental pressures which they had no deliberate aims in creating. In humans the reverse is true.

We change because of alterations in nature we have generated on purpose. This is true of all cultures, no matter how simple or complex their technological repertoires. “The animal destroys the vegetation of a locality without realising what it is doing. Man destroys it in order to sow field crops on the soil thus released, or to plant trees or vines which he knows will yield many times the amount planted”.

Even the simple hunter gatherers, by manufacturing weapons, have transformed themselves from the prey of larger animals into apex predators. When Homo sapiens began to spread around the globe, we quickly turned every climate into our stalking ground.

We did not do this by genes alone, i.e. by the direct endowments of nature. We did it for the opposite reason, we lack the traits to tackle any particular environment, and have thus been forced to evolve a general cognitive toolkit to handle any environment. This instinct Engels called labour.

Engels’ approach is thoroughly materialist, and for this reason many evolutionary theorists cannot accept it. The tendency to attribute all of human development to ideas remains the mainstay of popular science literature. The likes of Steven Pinker and Yuval Harari say that storytelling, and the ‘Machiavellian individualism’ of humans explains how we have come to dominate the planet.

There has been some resistance to this idealism, however, but few outside of the academy know about it. In particular, the field of Cultural Evolutionary Theory which has become very popular in evolutionary anthropology departments takes a line quite similar to Engels.

Its chief theorists, the aforementioned Boyd, as well as Richerson, Henrich, and others, acknowledge that the development of the productive forces is necessarily cumulative. They appreciate that no single individual could reconstruct their way of life from individual intelligence alone. They say that this cumulative aspect is the “secret of our success”.

However, cultural evolutionary theory still makes the mistake of failing to distinguish between the economic base and the superstructure of society, lumping all aspects of human social life together under the heading of “culture”. This can lead to certain idealistic tendencies.

Nevertheless, nearly 150 years after this pamphlet was written, the tide has very much turned in Engels’ favour. The sheer weight of evidence has dragged the bourgeois anthropology departments towards the Marxist view of prehistory.

Most of them do not realise this, however, and those that have noticed it despise this trajectory. It is just as Stephen Jay Gould once pointed out. “The deeply rooted bias of Western thought predisposes us to look for continuity and gradual change”. However, students of the real history of evolution would have saved themselves a lot of effort if they had merely paid attention to Engels from the start!

Engels achieved this “brilliant exposé” because his philosophical outlook more accurately corresponded to the real world. He saw that change in nature must be understood dialectically, and by applying this method consciously was able to penetrate into the ancient past.

None of this is to suggest that dialectical materialism, on its own, is a “magic master key for all questions”, as Trotsky explains. We still need data to draw reliable theoretical conclusions, and Engels was clearly limited by his lack of information, which forced him to speak on the question quite abstractly.

Nonetheless, he proved that philosophy is necessary for science. At this stage of development, the only philosophy that can take science forward is Marxism.

The revenge of nature

Engels was keen not to flatter humanity too much. For every plan we execute successfully some unforeseen reaction from nature tends to humble us:

“Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first…Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people, like someone standing outside nature – but that we, with flesh, blood and brain, belong to nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.”

Perhaps no time in history has nature threatened to take its revenge upon us quite like today. Global warming, should it continue at its current rate, will make human civilization as we know it impossible. As things stand, human society has proven incapable of reversing course. But Engels continues:

“And, in fact, with every day that passes we are acquiring a better understanding of these laws and getting to perceive both the more immediate and the more remote consequences of our interference with the traditional course of nature. In particular, after the mighty advances made by the natural sciences in the present century, we are more than ever in a position to realise, and hence to control, also the more remote natural consequences of at least our day-to-day production activities.”

Indeed, today we at least have the advantage of knowing exactly what we are doing wrong, and what technologies are required to fix the problem. Capitalist production, however, and the capitalist class whose outlook is determined by this mode of production, ignores all that it yields beyond the intended profit, rendering a solution impossible. Moreover, expanding humanity’s control over nature any further is impossible under this system, which is completely anarchic. In the search for short term profits, corporations pursue policies which are incompatible with continued human survival.

The final lesson of The Part Played by Labour, a lesson Engels never got to finish, is that the socialist revolution, which will usher in the planning of economic life, will transform humanity from the exploiters of nature, and of ourselves, into the custodians of nature, of which we are a part. In this way, our mastery over nature will become complete. We will leave behind the animal kingdom entirely, and finally become ourselves. As he explains in Socialism Utopian and Scientific:

“Man’s own social organisation, hitherto confronting him as a necessity imposed by Nature and history, now becomes the result of his own free action. The extraneous objective forces that have, hitherto, governed history, pass under the control of man himself. Only from that time will man himself, more and more consciously, make his own history — only from that time will the social causes set in movement by him have, in the main and in a constantly growing measure, the results intended by him. It is the ascent of man from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.”

References

Boyd, R., & Silk, J. B. (2018). How Humans Evolved (8th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Engels, F. (1876). The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1876/part-played-labour/index.htm#n1

Engels, F. (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/index.htm

Gould, S. J. (1977). Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History. W. W. Norton & Company.

Harcourt-Smith, W. H. E. (2010). The First Hominins and the Origins of Bipedalism. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 3(3), 333-340. doi: 10.1007/s12052-010-0257-6

Henrich, J. (2015). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

Henrich, J., & McElreath, R. (2003). The evolution of cultural evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 12(3), 123-135. doi: 10.1002/evan.10110