“The economic misery is too great in the masses… Economic misery is preparing the ground on which coups d’etat and revolutions flourish.”

(Report of the Prussian commissioner for internal security, early 1923)

It is exactly 100 years since the French bourgeoisie sent in 60,000 troops to occupy the Ruhr. This incident sparked the deepest economic collapse ever faced by a capitalist government up until this point. In doing so, it prepared a revolutionary crisis in Germany that threatened to bring down the entire system.

1923 was a year of great hunger, of hyperinflation, and of revolution. To this day, the authorities – especially in Germany – are haunted by this collapse and hyperinflation.

“Memories of the great hyperinflation of the 1920s continue to hold Europe’s most powerful nation in their historic grip,” wrote the New Statesman (27/9/2015). “It is an era that is still part of the national psyche today,” explained Der Spiegel.

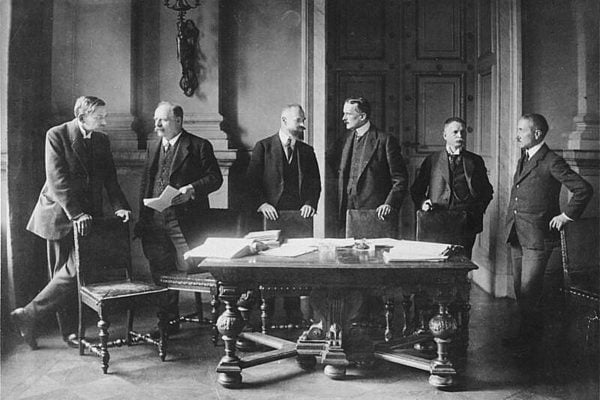

Treaty of Versailles

Germany was bled white by the Allied Powers following its defeat in the First World War. A draconian ‘peace’ treaty was imposed on it at the Paris Peace conference in 1919.

This ‘Treaty of Versailles’ was described by John Maynard Keynes as a “Carthaginian peace”. By this he was referring to the Romans’ destructive and humiliating pacification of their rival city-state Carthage, right down to salting the earth so that no crops would ever spring from its soil again. As a result, “the industrial future of Europe is bleak,” Keynes wrote, “and the prospects of revolution very good.”

Article 231 of the Treaty demanded reparations to be paid in 42 annual instalments. The stone-faced leaders at a London conference fixed the total German debt at 132 billion gold marks. This was an eye-watering sum, which was impossible to raise. In fact, Keynes calculated this figure to be three times more than the country could actually pay.

Germany was largely stripped of its military and forced to cede the key industrial region of Alsace Lorraine, and also half of Upper Silesia, with its important coal and ore reserves. It was forced to give up a quarter of its coal production. Reparations were also paid in kind, in ships, trains, wagons, and cattle. The Allies stripped Germany bare, which created acute shortages.

Successive German governments tried to lighten the burden through a series of currency devaluations, provoking major inflation. They had the illusion that this would massively reduce the German debt, since it was denominated in the now devalued German marks. But they were blind to the financial catastrophe that was being prepared.

Pauperisation

Printing money was not new. The German government liberally made use of the printing press during the war. By 1918, the amount of paper money in circulation had risen six-fold in comparison to 1913. As a result, by the end of the war, prices had doubled and the mark had declined to half its former gold value on neutral money markets.

The victorious imperialists were trying to wring blood from a stone. Given the intolerable burden, Germany pleaded for a moratorium on the reparations. The French flatly refused.

On 11 January 1923, the French government – which had ideas of breaking up the country – ordered its army to occupy the Ruhr to secure its interests. The Belgians followed suit. After all, both had debts of their own to pay.

The result would be the absolute pauperisation of practically the entire German working population within a matter of months. There is nothing more devastating than hyperinflation when it comes to destroying real wages and living standards.

It also destroyed the savings of the middle class, which was brought to ruin. In some ways, they could be worse off than the workers, as at least the latter could fight for wage increases. The middle class tended to rely on fixed incomes, rents, savings, and pensions.

The German people were literally starving. At the other end of the scale, gigantic fortunes were amassed within a period of a few months by the German capitalists.

Devaluation

The German government was facing complete bankruptcy and was desperate to try anything. Devaluation would bring benefits, they were told by the industrialists. It would make exports cheaper, thereby encouraging production, and would help to shrink the debt. It would also undermine ‘excessive’ wages.

In the year preceding March 1921, the international value of the German mark remained stable. Throughout 1922, its value fell. With the occupation of the Ruhr, it went into freefall.

In June 1922, one US dollar was worth 300 marks; in October, 2,000 marks; and in November, 6,000 marks. On 4 January 1923, a few days before French and Belgium troops entered the Ruhr, the dollar was quoted at 8,000 marks. By November 1923, one dollar was quoted at 2,520 billion marks!

Big business was radically opposed to any attempt to reverse the inflationary trend – namely, revaluing the currency – based on the argument that it would render German industry uncompetitive, thereby increasing unemployment.

Hugo Stinnes, the industrialist, was regarded as the most powerful man in Germany at the time. His philosophy was simple: the working class needed to make sacrifices to put German industry back on its feet.

“I do not hesitate to say that I am convinced that the German people will have to work two extra hours per day for the next ten or fifteen years”, explained Stinnes to the National Economic Council in October 1922.

“The preliminary condition for any successful stabilisation is, in my opinion, that wage struggles and strikes be excluded for a long time,” Stinnes continued. “We must have the courage to say to the people: ‘For the present and for some time to come, you will have to work overtime without any payment’.”

What Stinnes was demanding was a permanent reduction in working-class living standards and an economy based on permanently cheap labour.

Stinnes gleefully used the currency crisis to extend his empire from coal to electricity, banks, hotels, paper mills, newspapers, and other publishing ventures. Inflation was a means to increase the concentration and centralisation of capital into fewer hands.

Big business prospered as never before, as export profits were invested in stable currencies, while the nation was starving and the state facing bankruptcy.

Stinnes was determined, as a leading and ruthless member of his class, to revoke all the gains made by the working class in the 1918 revolution, especially the introduction of the eight-hour day.

Resistance

The new Wilhelm Cuno government, which was in the pocket of the Ruhr industrialists, called for ‘passive resistance’ in face of the foreign occupation – i.e. for resistance on their terms and with their methods. They were terrified of resistance led by the working class, who might then strike against the German capitalists as well.

The government called for a vote of confidence in this campaign, which was endorsed in the Reichstag by 284 votes to 12, with the Communists voting against.

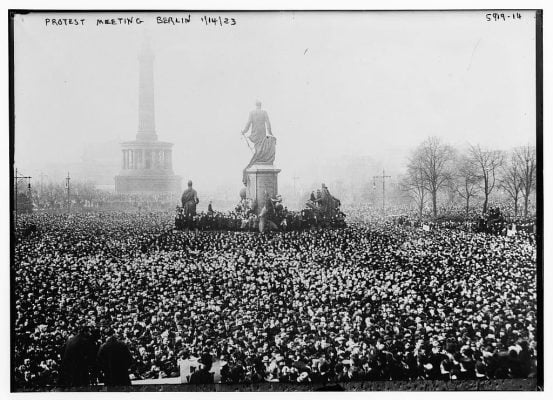

There would be no repatriation payments and no cooperation with the occupying forces. Mass demonstrations in opposition to the French troops took place everywhere, with 500,000 protesting in Berlin alone.

The Social Democrats supported the bourgeois government, and the trade union leaders met with the employers to organise ‘resistance’. Civil servants and local authorities were forbidden to cooperate. It was ordered that no workers should help the French authorities in any way, nor mine or transport goods.

The working class responded enthusiastically to the call to resist. Strikes, sabotage, and go-slows crippled the railways, mines, and telegraph centres. The occupation ground to a halt. It was a stage of siege.

In response, the French occupying forces tried to intimidate the workers by arresting and sacking those who resisted. French troops and officials replaced all those sacked, which only intensified the animosity.

Clashes increased and became more violent, leading to the death of a number of workers. French troops machine-gunned workers in the Krupp factories, killing 13 and wounding 30. On 29 January, they imposed martial law in the region. Despite this, the French only succeeded in moving 500,000 tons of coal between January and May.

In reality, the occupation achieved little, but simply drove Germany deeper and deeper into crisis. The French imperialists had destroyed any chance of further reparations.

The German employers eagerly joined the resistance against French occupation, while also denouncing any wage demands as ‘unpatriotic’. At the same time, they received huge loans, financed by the printing press, which they used to speculate against the mark.

Many workers could see through the so-called patriotism of the likes of Krupp, Thyssen, and Stinnes, the coal and steel magnates. The bourgeois parties also joined the resistance, but were always fearful that ‘passive’ resistance would spill over into class struggle. In fact, that is precisely what happened.

Class war

As time went on, the ‘national unity’ between the German workers and the bosses began to break down. In fact, German employers cooperated with the coal deliveries to the French as long as they were paid in cash.

Meanwhile, the country was being torn apart. Class interests begin to shift to the forefront. The bourgeois parties vacillated and began to get cold feet. Inflation turned to hyperinflation, as the working class became increasingly impoverished.

There was increased anger against the capitalist profiteers. In the meantime, the Communist Party, which was very large, swung behind the resistance, while giving no credence to Cuno. As a result it began to play a leading role against the occupation.

Increased repression by the French troops only served to increase the militancy of the workers. The Essen postal workers were arrested for planning a strike, but this only increased their determination. Sabotage increased, as railway lines were ripped up and pipelines severed.

“The struggle, which had begun as a national resistance against the French,” wrote Evelyn Anderson, “ended in a period of the fiercest class war that Germany had ever experienced.” (Anderson, Between Hammer and Anvil, p.91)

The growing sentiment of class war then turned to calls to overthrow the Cuno government. The workers were no longer interested in parliamentary niceties. Already in April, a conference of the miners’ union called for the end of passive resistance.

Under the impact of the crisis, the German workers underwent a colossal radicalisation. They increasingly turned their backs on the reformist Social Democrats and turned towards the Communist Party.

Under the guidance of Lenin and Trotsky, the Communist Party adopted a united front policy to rebuild its support among the working class. Membership now stood at 222,000: the biggest of the communist parties outside of the Soviet Union.

Fascist gangs also raised their heads, especially in Bavaria, inspired by Mussolini’s successful march on Rome some months earlier. But their base was small, and Hitler’s attempted putsch in November would end in complete failure. The tide throughout Germany was flowing in the direction of revolution.

Hyperinflation

Very soon, barrowfuls of paper money were needed to buy even the basic necessities. Postage stamps needed to be continually printed over with new values of millions of marks to replace the original costs as they went out of date.

Workers, after receiving their paper wages, would need to rush off and spend them before they became worthless. Wads of useless money were even used to light stoves. Dr. Schacht, Germany’s National Currency Commissioner, explained that at the end of the war one egg could in theory have been exchanged for five hundred million eggs some five years later!

Living standards simply collapsed. The middle classes took trains to the countryside with valuable heirlooms and jewellery, which they exchanged for sacks of potatoes and cabbages. Goods in the shops vanished. Pensioners received 10,800 marks in July 1923, enough only for two tram journeys, as long as they were quick enough to spend it.

The rate of interest rocketed. It was 100 percent for a 24-hour loan, 400 percent for a month, and 5,000 percent for a year. No one wanted paper marks. The capitalists collected their profits in dollars or gold, and simply paid their debts in paper, making a handsome profit in the process.

Prevarication

Things had become utterly intolerable. However, the Communist International (‘Comintern’), headed by Zinoviev, instead of discussing a concrete plan for revolution in Germany, centred all its discussion on the threat of fascism.

“Germany is on the eve of revolution,” declared Zinoviev. But he went on: “This does not mean that revolution will come in a month or in a year. Perhaps much more time will be required.”

When the German Communist leaders arrived in Moscow seeking advice on how to cope with the growing revolutionary wave in Germany, they were ill-advised by the Comintern leaders. Lenin had suffered his third stroke in March 1923, which rendered him completely paralysed. Trotsky was away, suffering from illness.

Stalin’s advice was to hold back. “Should the Communists at the present stage try to seize power without the Social Democrats? Are they sufficiently ripe for that?” Stalin asked.

“That, in my opinion, is the question. When we seized power, we had in Russia such resources in reserve as a) the promise of bread; b) the slogan: the land to the peasants; c) the support of the great majority of the working class; and d) the sympathy of the peasantry. At the moment the German Communists have nothing of the kind.

“They have of course a Soviet country as neighbour, which we did not have; but what can we offer them? Should the government in Germany topple over now, in a manner of speaking, and the Communists were to seize hold of it, they would end up in a crash. That, in the ‘best’ case. Whilst at worst, they will be smashed to smithereens and thrown away back.

“The whole point is not that Brandler wants to ‘educate the masses’, but that the bourgeoisie plus the right-wing Social Democrats are bound to turn such lessons – the demonstration – into a general battle (at present all the odds are on their side) and exterminate them [the German Communists].

“Of course, the fascists are not asleep; but it is to our advantage to let them attack first: that will rally the entire working class around the Communists (Germany is not Bulgaria). Besides, all our information indicates that in Germany fascism is weak. In my opinion, the Germans should be restrained and not spurred on.” (quoted in Trotsky, Stalin, p.530, emphasis added)

In the end, despite the situation being extremely ripe for a successful revolution, the German Communist leaders, following the advice from Moscow, dragged their feet. This approach had disastrous consequences and led to the defeat of the German revolution of 1923. This is not the place for a full analysis of that defeat, which we have made elsewhere. [See Rob Sewell, Germany 1918-1933, Socialism or Barbarism]

The German Communist Party was faced with the same crisis as that which faced the Bolshevik Party in October 1917.

As the time approached to take power in Russia, vacillation gripped sections of the leadership, with Zinoviev and Kamenev coming out against the insurrection. It was only by the presence of Lenin and Trotsky that they were able to overcome this crisis and carry through the revolution.

Unfortunately, in Germany in 1923, there was no Lenin or Trotsky present. The majority of the German Communist leadership prevaricated and allowed the favourable opportunity to pass.

Bleak future

Today, the capitalist world is facing another deep crisis. The war in Ukraine has intensified the contradictions of the system. The rise of inflation, a phenomenon that was once considered dead, is inflaming the situation, as is the rise in interest rates. Both factors are pushing the world economy towards a major slump.

Europe in particular is facing a catastrophic situation as gas supplies from Russia are cut, which threatens widespread blackouts and the closure of industries. Germany will be especially hard hit, given its reliance on Russian gas supplies. It is at the centre of Europe’s energy crisis.

In 2021, at least 15 European countries got half their gas from Russia. Germany’s largest producer of ammonia and urea was forced to shut its factories in Saxony-Anhalt, forcing up the cost of fertiliser. Dozens of other companies have followed suit.

No wonder that there is deep anxiety about the future in Germany. The voice of German industry, the BDI, warned of a “massive recession”. The front cover of Der Spiegel even recently asked: “Was Marx right after all?”

Europe will be thrown into a slump, meaning widespread unemployment. Many are anticipating a ‘winter of discontent’. More than that, what terrifies the strategists of capital is next winter, as gas storage is unlikely to be replenished without Russian supply.

The future looks very bleak in Germany. While the current crisis is not on the same scale as in 1923, it is the most serious situation faced by the working class in generations.

The 1923 crisis was precipitated by the French occupation of the Ruhr. Today, the occupation and war in Ukraine is also intensifying the capitalist crisis, which will run on and on. As in the past, new revolutionary convulsions will be on the order of the day. No country will be immune.