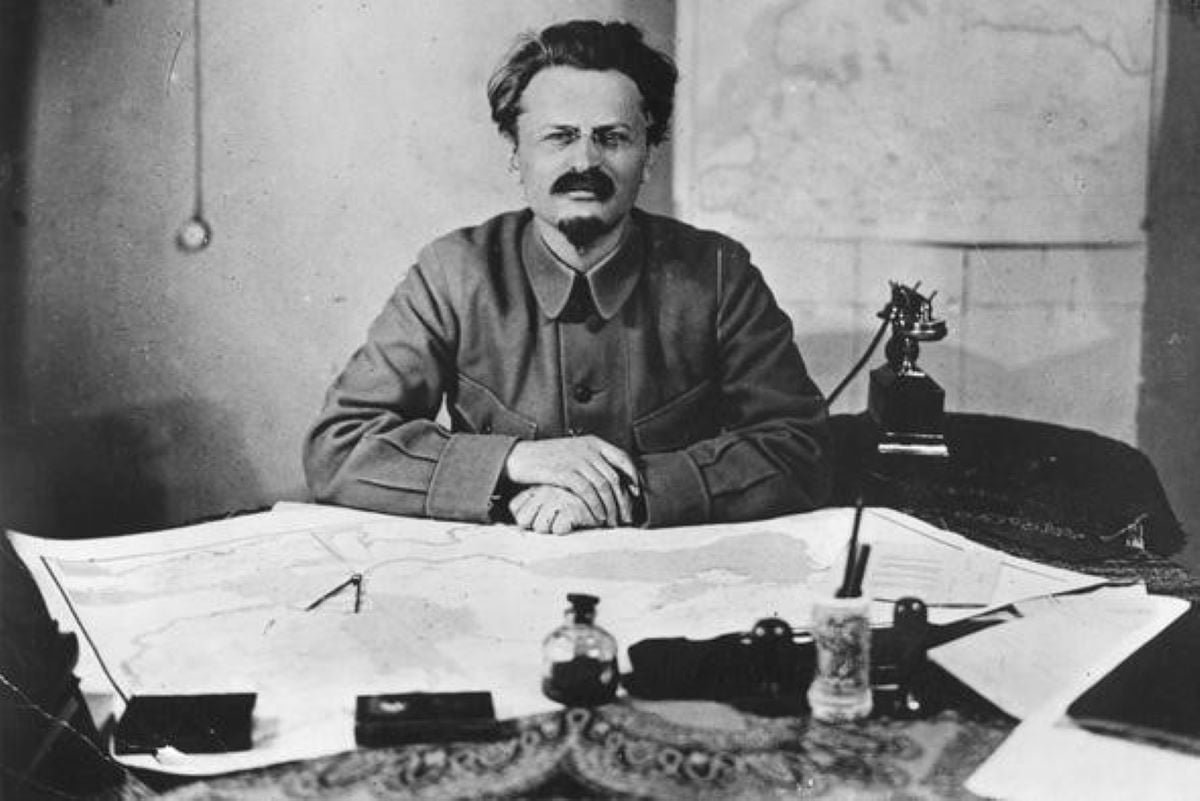

At the end of October, the Morning Star responded to its readers who were asking questions about the great Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

The paper’s response can be summed up as: “Trotsky himself was alright, but ‘Trotskyism’ is very bad.”

Marxists should welcome any attempt to engage seriously with revolutionary history and theory, as this provides a guide to our action today.

Unfortunately, though, what the Morning Star says doesn’t make much sense. If Trotsky made a “huge contribution to the Russian revolution” and was “effectively Lenin’s second-in-command”, as the article says, he must have done so because of and in accordance with his ideas.

Permanent revolution

Why, then, does the Morning Star take such a strong dislike to revolutionaries who fight for those ideas today?

Why, then, does the Morning Star take such a strong dislike to revolutionaries who fight for those ideas today?

It seems to be because the author of the article doesn’t really understand Trotsky’s ideas.

For example, the author is unhappy about the idea of ‘permanent revolution’. This is surprising given that the article is written in the name of the Marx Memorial Library. A quick glance through the texts in that library will reveal that it was Marx himself who first used the term ‘permanent revolution’ in 1850.

The theory of permanent revolution is the idea that in economically-backward countries, dominated by imperialism, only the working class (not the ‘progressive’ capitalists or liberal middle-class) is capable of carrying out the basic tasks of the democratic revolution which in turn become the tasks of the socialist revolution.

Alongside that is the idea, particularly important in countries dominated by imperialism, that only international socialist revolution can secure the gains made by the revolutionary masses in any one particular country.

In other words, permanent revolution is opposition to class collaboration, and for internationalism. These concepts are not exclusive to Trotsky.

On class collaboration Lenin wrote, in 1905:

“The bourgeoisie in the mass will inevitably turn towards the counter-revolution, towards the autocracy, against the revolution, and against the people, as soon as its narrow, selfish interests are met, as soon as it ‘recoils’ from consistent democracy (and it is already recoiling from it!)…

“…There remains ‘the people’, that is the proletariat and the peasantry. The proletariat alone can be relied on to march on to the end, for it goes far beyond the democratic revolution. That is why the proletariat fights in the forefront for a republic and contemptuously rejects stupid and unworthy advice to take into account the possibility of the bourgeoisie recoiling.” (Works, vol.9, p.98)

Making similar points about working class independence in 1850, Marx said:

“[The German workers] must contribute most to their final victory, by informing themselves of their own class interests, by taking up their independent political position as soon as possible, by not allowing themselves to be misled by the hypocritical phrases of the democratic petty bourgeoisie into doubting for one minute the necessity of an independently organized party of the proletariat. Their battle-cry must be: The Permanent Revolution.”

On internationalism, Lenin wrote in 1918 that: “We shall achieve victory only together with all the workers of other countries, of the whole world…” And Marx enshrined in the statutes of the First International that: “The emancipation of the workers is not a local, nor a national, but an international problem.”

It was precisely because he held these ideas, along with Lenin, that Trotsky played such an important role in the Russian Revolution.

Class collaboration

After the workers’ movement had overthrown the Tsar in February 1917, the pressure of middle-class public opinion caused the workers’ leaders to vacillate and offer their support to the bourgeois provisional government, in a class-collaborationist manner.

After the workers’ movement had overthrown the Tsar in February 1917, the pressure of middle-class public opinion caused the workers’ leaders to vacillate and offer their support to the bourgeois provisional government, in a class-collaborationist manner.

From exile, Lenin and Trotsky condemned this. But inside Russia, Stalin and Kamenev directed the Bolsheviks to support the class collaboration line. Both of them published articles supporting the bourgeois government’s continuation of the imperialist war, and censored Lenin’s letters from abroad criticising their position.

Stalin gave a speech at the First All-Russian Conference of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in March 1917, where, against Lenin’s slogan of “no trust in and no support of the new government”, he offered critical support to the provisional government as a kind of loyal opposition.

“Insofar as the Provisional Government fortifies the steps of the revolution, to that extent we must support it,” said Stalin.“But insofar as it is counter-revolutionary, support to the Provisional Government is not permissible.”

Only when Lenin returned from exile and delivered his April Theses was the line of the Bolsheviks corrected, away from Stalin’s class collaboration and towards the Marxist idea of permanent revolution.

It was thanks to this policy, advocated by Lenin and Trotsky, that the working class took power in October 1917.

This is why clear ideas are so important. Without them you make potentially fatal mistakes in practice.

Betrayals and defeats

Stalin and his allies, for example, repeated the same class-collaborationist mistake they made in 1917: in China and Britain in the 1920s, and in France and Spain in the late 1930s.

Stalin and his allies, for example, repeated the same class-collaborationist mistake they made in 1917: in China and Britain in the 1920s, and in France and Spain in the late 1930s.

In the early 1930s, they adopted the mirror-image of that policy – one of extreme ultra-leftism, known as the ‘Third Period’.

Those mistaken ideas led directly to the downfall of revolutionary movements. The Stalinised Communist Parties used the authority of the Russian Revolution to put themselves at the head of the workers’ movements, only to lead them to defeat.

The Morning Star objects to the description of such behaviour as a betrayal. But it’s hard to see what else to call it.

Despite all this, the Morning Star seems to disparage revolutionary organisations that have “core beliefs…as a condition of membership and essential for the achievement of their goals”.

All of history teaches us that without clear ideas it’s impossible to achieve our goals, because our goals are not to manage capitalism or to collaborate with the bourgeoisie, but to overthrow capitalism as a whole.

Building a serious revolutionary organisation requires a serious approach to revolutionary theory as our guide to action.

‘Broad alliances’

Unfortunately, the Morning Star does not have clear ideas. At the end of the article, it says:

“The responsibility of all genuine socialists today must be to seek the best way to reverse capitalism’s drive to shift the burden of its crises onto our planet and its peoples, and to work towards a socialist society by building the broadest possible alliances, in the workplace and in communities, to achieve that goal.”

The entire history and logic of capitalism is to concentrate wealth at one end of society and misery at the other, as Marx and Engels explained. But the Morning Star says we should “seek the best way to reverse capitalism’s” basic functioning by “building the broadest possible alliances”.

This is a utopian impossibility. It leads us directly down the path of mild reformism, in alliance with ‘progressive’ capitalists and the liberal middle-class.

Sadly, this has long been the editorial line of the Morning Star, which explicitly follows the Communist Party’s programme: Britain’s Road to Socialism.

The consequences of this editorial line were on display earlier in October, when the Morning Star published an article by GMB union general secretary Gary Smith demanding that the British trade unions support sending weapons to the Ukrainian military.

This demand places the Morning Star firmly in the camp of NATO and western imperialism.

Is this what “building the broadest possible alliances” looks like? It has nothing in common with the revolutionary internationalist position on war defended by Lenin. It has much more in common with the class-collaborationist position put forward by Stalin in 1917.

Likewise, in an editorial published in September the Morning Star chastised those putting forward anti-monarchy slogans as “individualist”, “self-righteous”, and displaying an undemocratic “rejection of the legitimacy of majority opinion”.

This is a capitulation to the pressure of middle-class public opinion, in the manner of the Mensheviks in 1917. This is inevitable if your strategy is “building the broadest possible alliance” through class-collaboration.

Revolutionary theory

Once again, Marxists welcome any attempt to engage seriously with revolutionary history and theory.

Once again, Marxists welcome any attempt to engage seriously with revolutionary history and theory.

The best approach is to read Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky for ourselves, measure what they said against the historical record and current events, and make up our own minds.

This is how we sharpen our understanding of capitalism and the class struggle. Such knowledge is a powerful weapon, with which we can change the world.

For an in-depth analysis of the life and ideas of Leon Trotsky, we recommend this article by Alan Woods from 2000, marking the 60th anniversary of the assassination of the great Russian revolutionary at the hands of a Stalinist agent.

Or visit Wellred Books to browse various classic texts by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky, alongside other titles by authors from the International Marxist Tendency – including ‘Lenin and Trotsky: What they really stood for’.