On 11 November 1975, Australia’s democratically-elected Labor government under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was forcibly dissolved by the British monarchy.

This unprecedented ‘constitutional coup’, carried out by the obedient lackeys of British imperialism, was an unvarnished attack on democracy that starkly reveals the depths of hypocrisy to which imperialism is willing to sink in order to defend its interests.

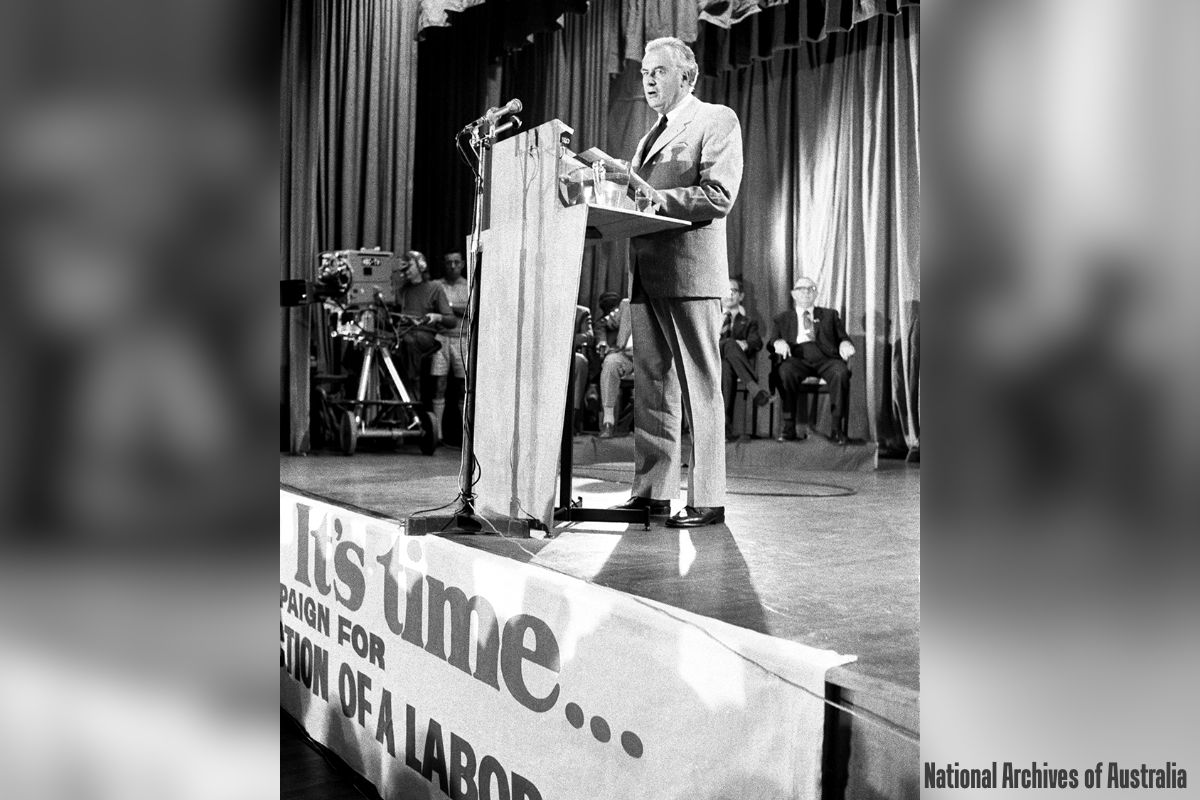

Whitlam first came to power in 1972 in a period of great upheaval. As the bodies of Australian soldiers sent to fight for US imperialism in the Vietnam War continued to pile up, the rose-tinted optimism of the postwar period was fading.

In its place came a mood of bubbling discontent among the working class, whose expectations had been lifted by the postwar boom, only to be smashed by 20 years of rule by the deeply racist, warmongering Liberal-Country Coalition.

In this context, Whitlam’s Labor Party won almost 50 percent of the votes at the 1972 elections to the House of Representatives (the lower house of the Australian parliament).

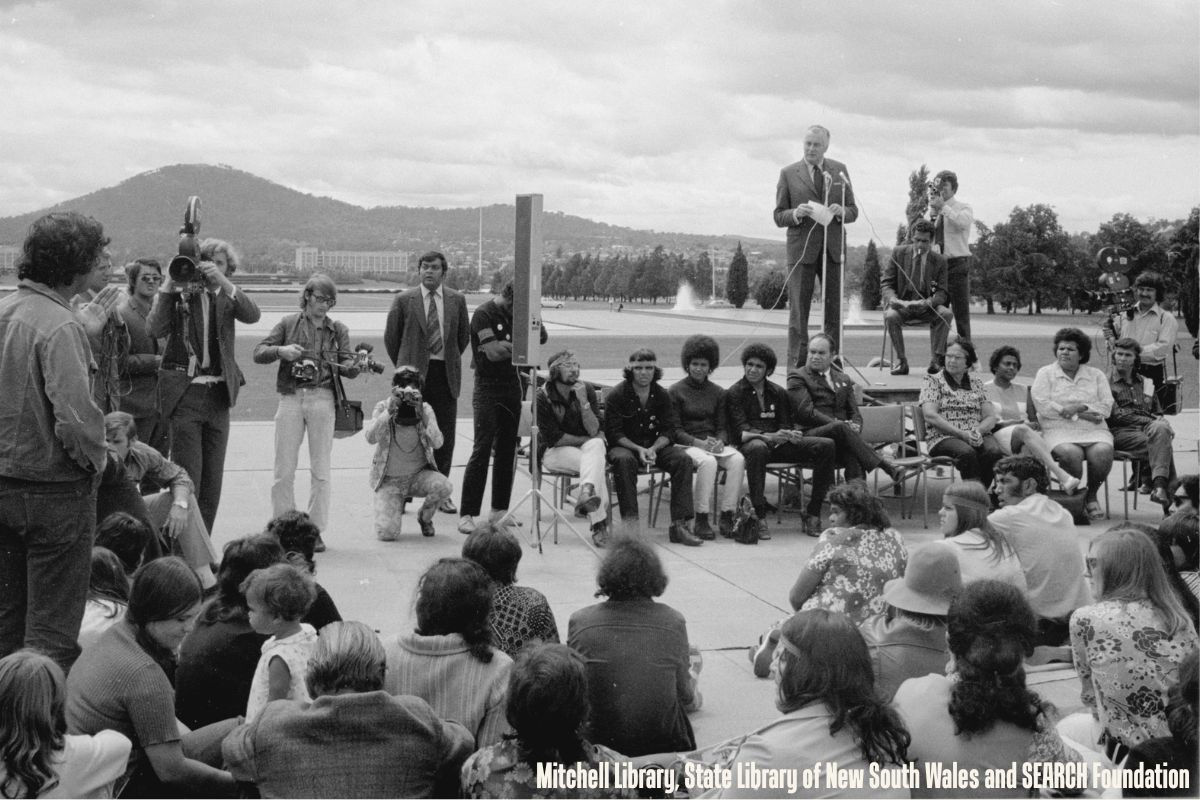

This was achieved through a series of progressive promises including ending Australian involvement in the Vietnam War, improving the lives of Indigenous people, funding schools and hospitals, and granting self-determination for the Australian colony of Papua New Guinea.

Whitlam was by no means a revolutionary, but his time in government from 1972-1975 represents one of the clearest attempts to put a left-reformist programme into practice.

In the first two weeks of Whitlam’s government alone: military conscription was de facto abolished, Australian troops were recalled from Vietnam, many racial discrimination laws were abolished, taxes on contraceptives were eliminated, and much more.

Labor passed sweeping reforms in this period, focussed on improving housing, healthcare and education, with a record-breaking 254 parliamentary bills introduced in 1973 alone. But the initial ease with which Whitlam’s policies could be implemented in the ‘lucky country’ was soon to turn into its opposite.

The not-so-lucky country

As always under capitalism, it is not the will of well-meaning politicians that decides when reforms can be implemented, but the stubborn facts of economic growth and the pressure of the class struggle.

In his maiden parliamentary speech, Whitlam stated that his policies would be funded by “the automatic and inevitable massive growth in Commonwealth revenues” that could be sourced from the growing economy.

While such growth may well have been ‘inevitable’ in the midst of the postwar boom, by the mid-70s this was no longer the case. As exports stagnated and Australia’s traditional imperialist backers – the US and UK – increasingly turned their attention elsewhere, the money for Whitlam’s reforms evaporated before his eyes.

In 1972 the Australian capitalist class and their imperial overlords had tolerated Labor as a safe, parliamentary outlet for the frustration of the masses alongside the traditional parties of the ruling class.

This cautious acceptance vanished, however, when Whitlam announced that money for his policies would be sourced from Middle Eastern loans, reduced foreign ownership of Australia’s substantial mining industry, and stricter regulation of the finance sector.

Whitlam’s dogged opposition to foreign ownership of key industries was a particularly sore point for the imperialists. In 1972, over half of the mines in Australia were owned by companies overseas, and the dramatic mining boom of the 1960s had meant that bosses in imperialist countries abroad were able to net billions in lucrative mineral exports.

As Labor postured about restricting the dominance of foreign capital, an immense wave of media slander was unleashed, in order to prepare the ground for what was to come. Bourgeois media was filled with allegations of scandals and corruption, often based on entirely fabricated ‘evidence’.

But the reality of the slanders was of no concern to the ruling class. Whitlam’s left reformism, in daring to threaten the profits of the imperialists to even the slightest degree, had signed its own death warrant. All the imperialists had to do was lie in wait for a moment to deal the killing blow.

The dying days of the Whitlam government

Whitlam’s moment of truth came in 1975. By this time, the Labor Party had utterly lost the confidence of the ruling class, at home and abroad. The powerful Senate (Upper House), which was dominated by the right wing, were able to effectively block the government from passing laws.

The concerted efforts of the entire Australian establishment aimed to cripple the Whitlam government, paralyse its attempts to carry out its programme, and discredit it in front of the masses.

The working class, however, were not blind to the machinations of the Senate and the capitalist class. Opinion polls showed 70 percent of the public opposed the deadlock in parliament and supported the passing of Whitlam’s programme.

Rallies and demonstrations organised by the labour movement, as well as talk of nationwide strikes, showed that the true mood in society was firmly against the Senate.

These bold mobilisations – not the interminable discussions in the parliament – represented the real democratic will of the people. It would not have been hard for Whitlam to have appealed to the working class on this basis, calling out the saboteurs in Canberra and showing the class interests behind the political deadlock.

By firmly waging the class struggle, the mighty facade of the capitalist state could have been torn away, to reveal the petty capitalist and imperialist interests behind it.

Yet Whitlam did no such thing, and in this we see once again the Achilles’ heel of all left reformists – their illusions in bourgeois democracy.

In fact, Whitlam did almost everything he could in his attempts to outmanoeuvre the right wing, except for relying on the one force that could allow him to be successful: the working class.

And so, the final months of Whitlam’s time in power were spent with relentless hand-wringing, with which little was achieved. Failed legislation was rewritten and re-debated, only to be rejected once again by the Senate.

Political enemies were bought-off with diplomatic positions, only to then be convinced otherwise by the Opposition – leading to such farcical events as the ‘Night of the Long Prawns’, in which an opposition Senator, having been offered a lucrative diplomatic job by Whitlam in return for leaving politics, was prevented from resigning by his colleagues who distracted him with whiskey and seafood.

But while politicians on both sides engaged in ludicrous bargaining in the hallowed halls of the parliament, the pressure of the masses on the streets only continued to build. The working class had experienced the concrete victories of the first two years of Whitlam’s government, and were not keen to see it brought to a standstill by right-wing provocateurs.

This was what worried the imperialists and the Australian ruling class more than any parliamentary manoeuvres. And so, on 11 November 1975, the British monarchy intervened to end the deadlock once and for all.

The monarchy’s ‘constitutional coup’

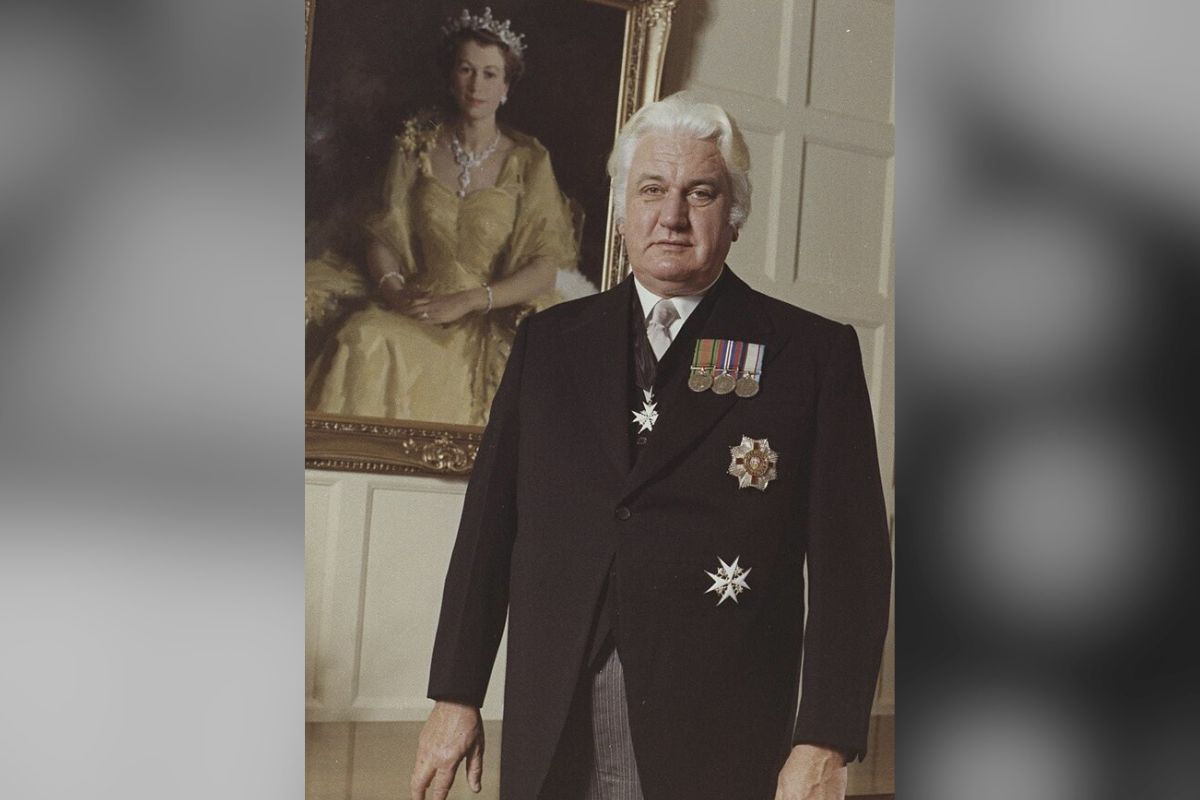

The highest representative of the establishment in Australia during the Whitlam government was Governor-General John Kerr.

Australia’s Governor-General, much like King Charles himself, holds the right to approve or disapprove laws, call an election and most importantly, dismiss an elected government. All of this can be done with the flimsiest of justifications, according to the whims of the ruling class.

The British monarchy and its undemocratically appointed representatives in its former colonies tend to remain in the shadows of politics and preserve a cultivated reputation as ‘apolitical’ and ‘impartial’.

The case of the Whitlam government, however, shows the true nature of the monarchy as a reserve weapon of the ruling class, to be wielded in the class struggle when its traditional methods of repression prove inadequate.

On 11 November, Whitlam met with Kerr with the intention of asking permission for the reelection of half of the Senate. This was to be the final of Whitlam’s innumerable attempts at solving the parliamentary deadlock on a constitutional basis.

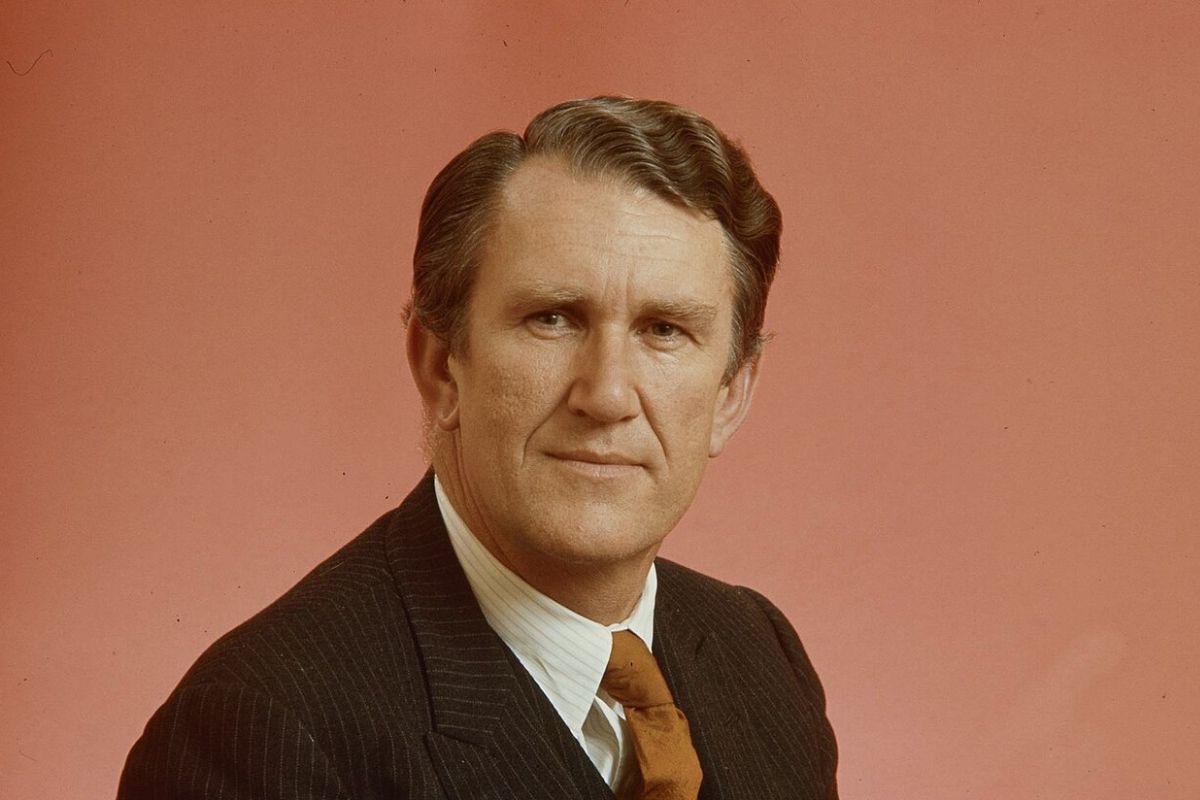

Before his request was even heard, however, Kerr informed Whitlam that his government had been dissolved, and that Liberal Party leader Malcolm Fraser was to take his place.

This was an unprecedented attack on Australia’s supposedly ‘democratic’ state, in which an imposed lackey of British imperialism was allowed to simply dismiss a sitting Prime Minister, without prior warning.

This ‘constitutional coup d’etat’, as Whitlam described it, was immediately met with outrage from the working class across Australia.

Spontaneous political strikes broke out across the country, even against the will of the trade union leaderships. Tens of thousands attended rallies in Sydney and other major cities to condemn Kerr and the monarchy’s blatant interference in the democratic process.

In these conditions, it would have been relatively simple for the Labor party to use the clear will of the masses to justify resisting the dismissal.

Such was the anger of the masses that Bob Hawke – president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions and future Labor Prime Minister – stated that it had the potential to “unleash forces in this country the like of which we have never seen.”

With a bold leadership, the situation could have rapidly evolved in a pre-revolutionary direction, but the Labor Party was keen to be anything but bold.

In his book on the events of his dismissal, Whitlam admitted considering defying Kerr and continuing to hold parliament against the will of the monarchy. This would have sent a defiant message that undoubtedly would have inspired the confidence of vast layers of the working class.

Here too, however, Whitlam’s aversion to the class struggle got the better of him. He wrote:

“Mr. Scholes [a fellow Labor politician] and I discussed maintaining or resuming the sittings of the House. It was in this context that I said to him in those circumstances Sir John [Kerr] would call out the troops. Many people still think it incredible that Sir John could have done that.

“If, however, a man can interpret the Constitution, where it is silent, in a way which entitled him to perpetuate his actions of that day, how much more certain is it that he would have thought himself entitled to act when, as the Constitution expressly states, ‘The command in chief of the naval and military forces of the Commonwealth is vested in the Governor-General as the Queen’s representative’.”

This statement shows the immense danger that reformist illusions pose for the struggle against imperialism in particular, and the class struggle in general.

It reveals Whitlam’s willingness to appease the ruling class at a critical juncture in the class struggle, preferring to surrender, rather than break with oppressive ruling class institutions once and for all.

If a representative of the British monarchy were to summon the army to forcibly expel an elected government from the parliament building, such an act would send a shockwave through society.

It would have laid bare the true ruthlessness of the British crown and exposed the extensive control over both politics and the military that is concentrated in the hands of a subservient flunkey of imperialism.

Irrespective of whether Kerr would indeed have summoned the military, Whitlam and the Labor Party buckled at even the suggestion of the whip of reaction.

Despite all their grandiose proclamations of the injustice of the dismissal, their unwillingness to go beyond symbolic words and gestures only gave validity to the actions of the monarchy. At precisely the time when the masses mobilised for a fight against imperialist meddling, their ‘leaders’ recoiled from the power that had been put in their hands.

The machinations of the monarchy

Given the apparent suddenness of Whitlam’s dismissal, for decades the British monarchy was able to shift the blame solely onto Kerr, who was presented as an independent operator, who dismissed the Whitlam government on behalf of the crown, but without their active involvement.

Indeed, it is undeniable that Kerr had a personal dislike for Whitlam’s government and its policies. His private letters from the period, now available online, reveal the sneering arrogance and distaste for the masses typical of a proud bureaucratic puppet of imperialism.

But previously secret correspondence between Kerr and various senior members of the royal family, which was made public in 2020 after a public legal campaign, reveals the true extent of the monarchy’s involvement in and support for Whitlam’s dismissal.

The so-called Palace Letters were a series of written discussions between Kerr, Queen Elizabeth and the future King Charles among others, on the question of Kerr’s approach to the Whitlam government and the possibility of his dismissal.

After 1975, these letters were sealed away in the shadowy vaults of Australia’s National Archives, with an embargo personally placed on them by the Queen, demanding that they remain under lock and key at least until 2027, at which point the monarch’s private secretary would then be at liberty to extend the embargo at their own discretion.

This criminal conspiracy of silence was clearly intended to cover up the intimate knowledge and despicable role played by the monarchy in the interests of British imperialism.

In the letters, senior royals and particularly the then-Prince Charles openly condone the dismissal of the government, tell Kerr to ignore the senior legal experts who had advised him against it, and even offer the Queen’s personal protection against any attempts by the Whitlam government to remove him from his post.

Despite the continuing claims directly from the palace, which were reiterated as recently as 2020, that the royal family played no part in the dissolving of Whitlam’s government, the reality proven by the Palace Letters is that they not only knew of the plans several months in advance, but actively participated in formulating them.

This is the despicable reality of the British monarchy as a tool of imperialism.

While in ‘normal’ times these aged parasites clothe themselves in the mystifying pomp and ceremony we are used to, they are by no means above getting their hands dirty in the class struggle – firmly on the side of the oppressors and exploiters.

This must be the lesson and the legacy of Whitlam’s dismissal. If a mild-mannered left reformist could provoke a months-long palace conspiracy in defence of the interests of imperialism, it does not take much to imagine how they would respond to a genuinely revolutionary party in a period of heightened class struggle.

For this reason, communists today have a duty to unmask the crimes of the monarchy and its intimate ties to imperialism. Perhaps even more importantly, the Whitlam dismissal shows us that we must have no illusions in the ‘constitutional’ – that is, bourgeois democratic – path to transform society.

Only by doing away with capitalism, imperialism and any decrepit monarchical remnants in their entirety can we guarantee that a revolutionary programme can be carried out.

This article is from the RCP’s pamphlet The Crimes of British Imperialism. To fight imperialism, we must scientifically understand what it is, and where it came from. This pamphlet is therefore aimed at arming communists in the revolutionary struggles to come, to end the system which caused these heinous crimes.

Order your copy today at Wellred Books Britain.