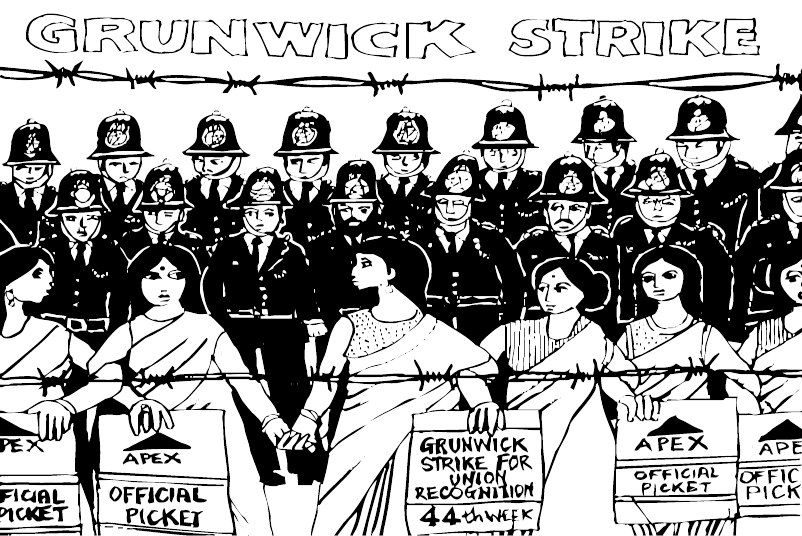

Leafy Dollis Hill and Willesden Green, sitting in the suburban London Borough of Brent, was hardly a centre of class struggle. But between 1976-78, this part of London would house one of the longest, most militant and violent strikes since WW2, led by ‘strikers in saris’.

Up until this point, struggles led by black and Asian workers; from the Bristol bus boycott, the Red Scar Mill in Preston, Mansfield Hosiery in Loughborough and Imperial Typewriters in Leicester, had shown white workers and trade unions had been at best passive, and at worst, outright parroted propaganda from the fascist National Front.

Grunwick however changed everything.

As the TUC later stated, “Grunwick strikers changed the face of British trade unionism”. In truth however, it was the culmination of all the previous struggles led by black and Asian workers and youth.

The Grunwick strike was led by Jayaben Desai. When she walked off the job, she defiantly said to manager Malcolm Alden:

“What you are running is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animal. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips. Others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager.”

Dickensian conditions

In the age before digital photography, Flickr accounts, and home printers, people took their rolls of film to chemists to be developed and glossy prints made. In many cases, this was not done by the chemist as such, but by outside firms who would be sent the film rolls by post, with the prints coming back to the shop a few days later.

One such firm in the 1970s was Grunwick, trading under such familiar names as Bonusprint, which occupied a shabby factory near Willesden Green in North-West London.

The Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories wasn’t a zoo, of course, but it was a miserable sweatshop with working conditions that Charles Dickens would have easily recognised. Pay was less than half the average wage (£28 for a forty hour week), hours were long with overtime enforced at any time.

The mainly-Asian workforce was un-unionised and subject to all manner of petty restrictions by management, from pregnant women not being given time off to visit the doctor, needing to ask to use the bathroom, to the condescending comments of Anglo-Indian George Ward, one of three founders of Grunwick, who called workers ‘my Asians’.

Conditions had been made worse over the summer of 1976 by the never-ending heatwave that had lasted through most of the season without a break.

On 20th August, all these tensions came to the fore as a Grunwick worker, Devshi Bhudia, was sacked for “working too slow”. Three other workers who were students working over summer, including Jayaben Desai’s son Sunil, walked out in support.

Foreman Malcolm Alden then sacked another worker, Jayaben Desai, without reason. The six together picketed the site and agreed to join a union,

Against all odds

The strikers first went to the Citizens Advice Bureau, who led them to a small union APEX (now part of the GMB), known for its right-wing leadership. It was hardly a promising sign given that all the British trade unions had given black and Asian workers at best a lukewarm response.

But APEX, a union for Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff, were desperate for members and had been losing many to rival unions.

A previous attempt in 1973 to get a union presence in the factory via the TGWU had failed. Everyone who tried was sacked. This time the six were able to get other workers to join the union and walk out on strike in support of the sacked employees and for better conditions.

APEX supported the strike and it was made official, and support for the workers quickly began to grow. The fact that the Grunwick management was refusing all talks and attempting to halt union recognition just added fuel to the fire.

The role of Jayaben Desai herself also cannot be underestimated. The 43 year old four ft 11 inch Gujarati from Tanzania was utterly determined and galvanised the workers with heroic courage and charisma.

Reporter: How long will you stay here?

Desai: Until we finish this dispute.

Reporter: A year?

Desai: Any time.

Reporter: Five years?

Desai: Ten years.

Solidarity

One thing soon became clear: Grunwick strikers were gaining the support of white workers in a way no previous struggle of black and Asian workers had previously.

Confidence was high given the recent union victory for equal pay at nearby Trico, a similar type of workplace to Grunwick.

Momentum was building. By September, 137 workers were now on strike, which was 28 percent of the total workforce.

Receiving and mailing out film and prints was crucial for Grunwick to operate. By November therefore, Desai called on the APEX to ask UPW (Union of Postal Workers) to cut off Grunwick’s mail to its customers. But they refused. So Desai herself went to the UPW branch at Cricklewood where Grunwick mail was sorted and she found support for their cause.

The workers were won over. Grunwick mail was ‘blacked’, meaning mail to and from Grunwick was refused to be handled. This left Grunwick management facing potential economic ruin within days.

Open solidarity action of this kind for a struggle led and by almost all black and Asian workers was unprecedented. But this was also actively fought for as members of the strike committee toured the county through help of Brent Trades Council.

They would visit mills, dockyards, mines and factories to win support of workers across the country. Over 42 weeks, the committee visited 2000 workplaces, galvanising the picket line from the initial 137 strikers.

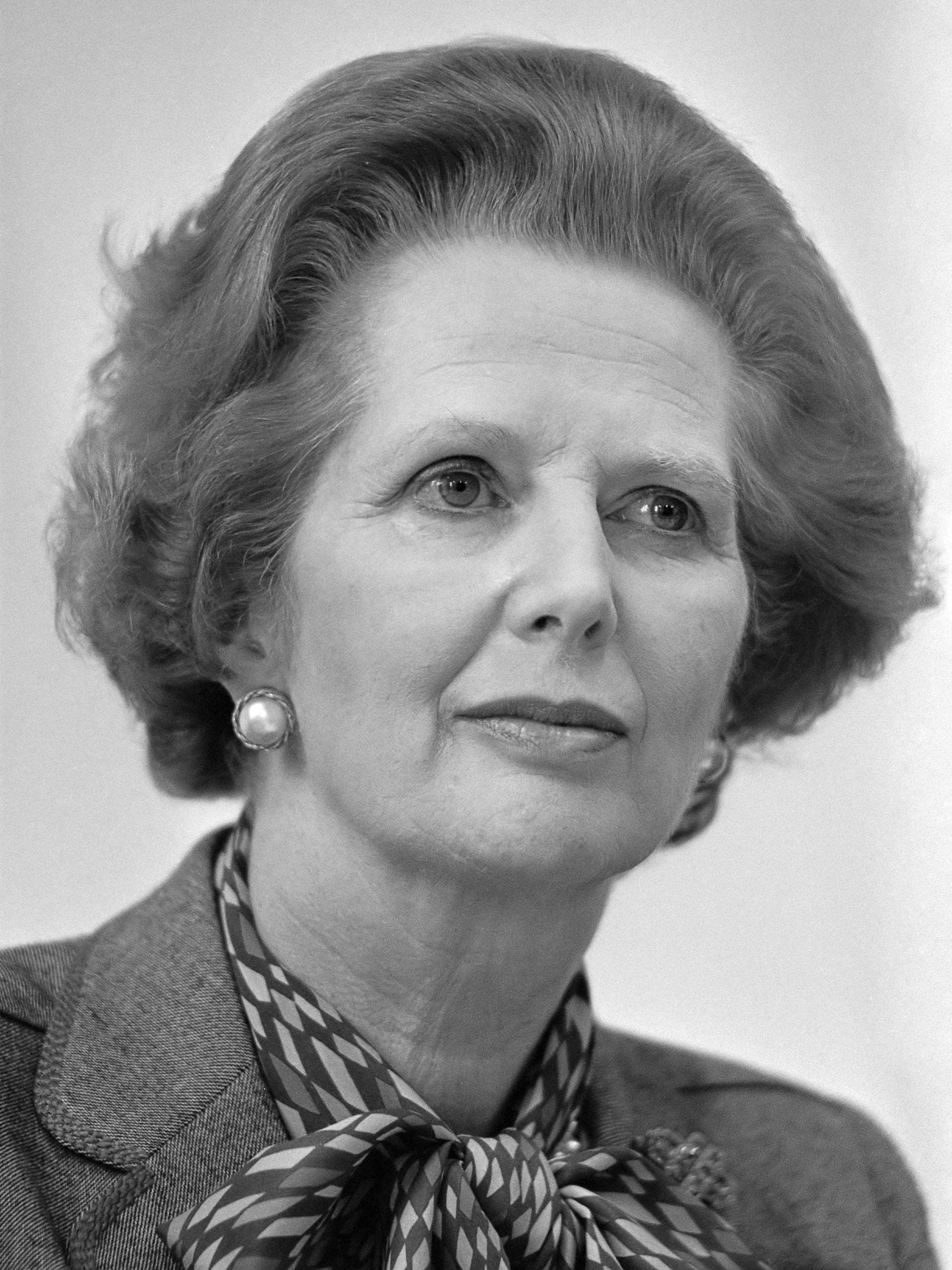

However, the Grunwick management was standing firm against the strikers and was receiving the full support of the Tory party, the national press and an organisation called the National Association for Freedom (NAFF), which backed Margaret Thatcher and a whole series of reactionary causes over the years.

This “secondary picketing” by the capitalists started to have its effect at the very top of the Labour movement, including the weak Labour government run by James Callaghan with a three seat majority.

A special debate was called at Westminster at the behest of Tory MPs to demand that the Labour government take action using existing laws to force the postal workers to handle Grunwick mail.

Under pressure from a nervous Labour leadership, the right-wing national leaders of the UPW put pressure on the local union to suspend the mail blockade in return for Grunwick management agreeing to talks via ACAS. Defeat was grabbed from the jaws of victory!

It soon became clear that Grunwick had no intention of honouring any ACAS negotiated agreement, which was not legally binding, and had indeed awarded a 15% pay increase to any worker at the site who would not join a union.

The later ACAS decision to support union recognition was rendered void by its failure to canvas all workers, even though Grunwick management had prevented such a survey from happening. In effect, the bosses could ride roughshod through the law.

State repression

By 1977, legal debates continued, but so did the strike. As spring turned to summer, mass pickets were organised outside the factory to ramp up the pressure and keep the fight alive.

A week of action was organised in June which highlighted both the solidarity of the British working class and the ugly essence of the British state as it enacted grotesque violence to physically crush the strike.

From the beginning of the strike, violence had characterised the response of the Grunwick management and the ironically named ‘National Association for Freedom’. Jayaben had been hospitalised when a manager drove his car over her foot. Another manager had driven his car into a female striker.

The week of action saw this violence ratched up by the state itself. The first day was a women’s picket and saw 84 of the 200 picketers arrested. Mary Davis, who was secretary of Haringey Trade Union Council, had her feet stomped on and crushed until she could not walk after being encircled by ten male police officers.

International Women’s Day.

Jayaben Desai – Grunwick

“What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager.” pic.twitter.com/IbU5EVu5v4— RotherhamTUC (@rotherham_tuc) March 8, 2023

Much of the violence was carried out by the infamous Met Police Special Patrol Group (SPG), a paramilitary force modelled on the repression carried out in the North of Ireland. This was the first time in British history a paramilitary unit was used to intervene in an industrial dispute.

At the mass protests, covert filming was done, and several police agent provocateurs were identified by union activists.

Over the course of the strike, around 550 people were arrested – an unheard of number for an industrial dispute in Britain. Similarly brutal tactics were later seen with the police attacks on the miners in 1984-85 and the Wapping print workers.

The Grunwick arrests were marked by the usual barrage of press reports about mob-violence, etc., and the Tories were not slow to join in. But the smears in the press did not stop the solidarity from the working class as a whole.

This International Equal Pay Day, we are featuring this @NPGLondon portrait of Jayaben Desai, a factory worker who led a strike for better pay and conditions in 1974. Use our Schools hub resource to examine how Desai was represented at the time, evaluating this newspaper… pic.twitter.com/ZOSsJeKcOl

— NPG Schools (@NPGSchools) September 18, 2025

On the 11th of July, 20,000 people travelled down to Willesden to support the strike. It was the largest labour solidarity march which included 3000 miners and even dockers who only two decades ago were marching with Enoch Powell!

Gita Sahgal, a striker shared how incredible the moment was:

“There were dockers and post office workers and miners…it was an amazing moment and I remember it particularly because what we’d known about the dockers was that they were racist. They were famous for their marches when Enoch Powell had made his inflammatory speeches…my abiding memory is that these white men had come in solidarity with Asian women in order to protect the idea of solidarity itself.” (Preeti Dhillion, The Shoulders we Stand On), p. 219

The action of the ‘strikes in saris’ unashamedly showed that it was militant class struggle which fought racism, transformed consciousness and changed the way white workers related to black and Asian people in the UK.

Labour leadership panic

As usual, the Labour and trade union leaders, who only wanted to have a quiet life, quickly became scared and, hostile to any signs of union militancy, began to look for a way out.

Minutes from the Callaghan Labour government on the 26th June 1977, which included the Prime Minister himself, stated:

“The Prime Minister said that people have to realise there was indeed a crisis. If things continued on the present basis there could well be fatalities and in circumstances which might be in danger of bringing the government down.”

The Labour government gave them a way out in the form of an official inquiry led by the ever-faithful Lord Scarman. The inquiry was used to try and wind the dispute down. APEX called off the pickets pending the outcome, allowing the initiative to be lost.

The strikers knew, however, that no learned judgement from Lord Scarman (or whoever was pushed forward) would bend the will of the Grunwick management, particularly over the issue of union recognition.

The bosses knew that their grip over a compliant workforce could not be maintained should there be a union presence. Scarman would in time kindly recommend the re-employment of the strikers and the recognition of the union, but the Grunwick bosses simply ignored the judgement.

They became the first employer to ever reject the result, and for good measure, the House of Lords, acting in the class interests of the bosses, made clear that the management did not have to recognise the union.

After an entire year of striking, by October 1977, the strike started to ebb. In November, sensing the ebb in the strike, the SPG used the ‘flying wedge’ tactic to violently attack a crowd of 8000 who had turned up to support the strike. 113 were arrested and 243 were injured in what was the most violent day of the protest.

The union leadership, afraid of what might happen, soon abandoned the strikers, who bravely carried on with rank-and-file support until defeat was finally admitted in July 1978.

Seeing APEX was turning their back on the strike, Jayaben Desai, determined as ever, and three others went on a hunger strike outside the Trade Union Congress (TUC) headquarters. For this, APEX kicked them out of the union for four weeks.

Fight to the finish

The strike failed to succeed in full because the tops of the trade union movement did not fight to the finish. Len Murray, head of the TUC, paid lip service to Grunwick, but did not countenance the idea which had been put forward to shut the power off at the Grunwick factory.

Rank and file white workers were willing to put their jobs on the line for the struggle. Cricklewood postal workers had taken to a second campaign to have Grunwick mail ‘blacked’, against the directives of the UPW.

Over a hundred postal workers were suspended and threatened with dismissal, and the UPW failed to back them or offer strike pay because the action was considered ‘unofficial’.

Compare this to the NAFF, who in cooperation with the police and the SPG who took violent measures outside the law in brutalising picketers. The NAFF, with police cooperation also helped complete 80,000 processed film orders under a code name ‘Operation Pony Express’.

Clearly the battle could have been won, but the labour leaders’ refusal to fight to the finish, coupled with the capitalist classes’ willingness to fight by any means necessary resulted in the Grunwick strikes defeat.

The strike was an early outlier of the brutal tactics Margaret Thatcher was to use to break the power of unions.

Nevertheless, the Grunwick strike remains a seminal moment in transforming the British labour movement. White workers rallied to the call of black and Asian workers in struggle in an unprecedented way.

Workers inside the factory won two pay increases during the strike. Conditions also improved enormously, healthy Christmas bonuses were shared and paid bank holidays were included.

Previous ideas of separate black unions were thrown into the dustbin of history as black and Asian workers forced themselves into the British labour movement – a legacy which we today take for granted today.

In the next instalment, we will see how the radicalism of the late 70s spread to south London, where the Battle of Lewisham saw the physical fight against the fascist National Front.