This article is from the RCP’s pamphlet The Crimes of British Imperialism.

To fight imperialism, we must scientifically understand what it is, and where it came from. This pamphlet is therefore aimed at arming communists in the revolutionary struggles to come, to end the system which caused these heinous crimes.

Order your copy today at Wellred Books Britain.

In December 1600, the East India Company was founded by a small group of merchants in London.

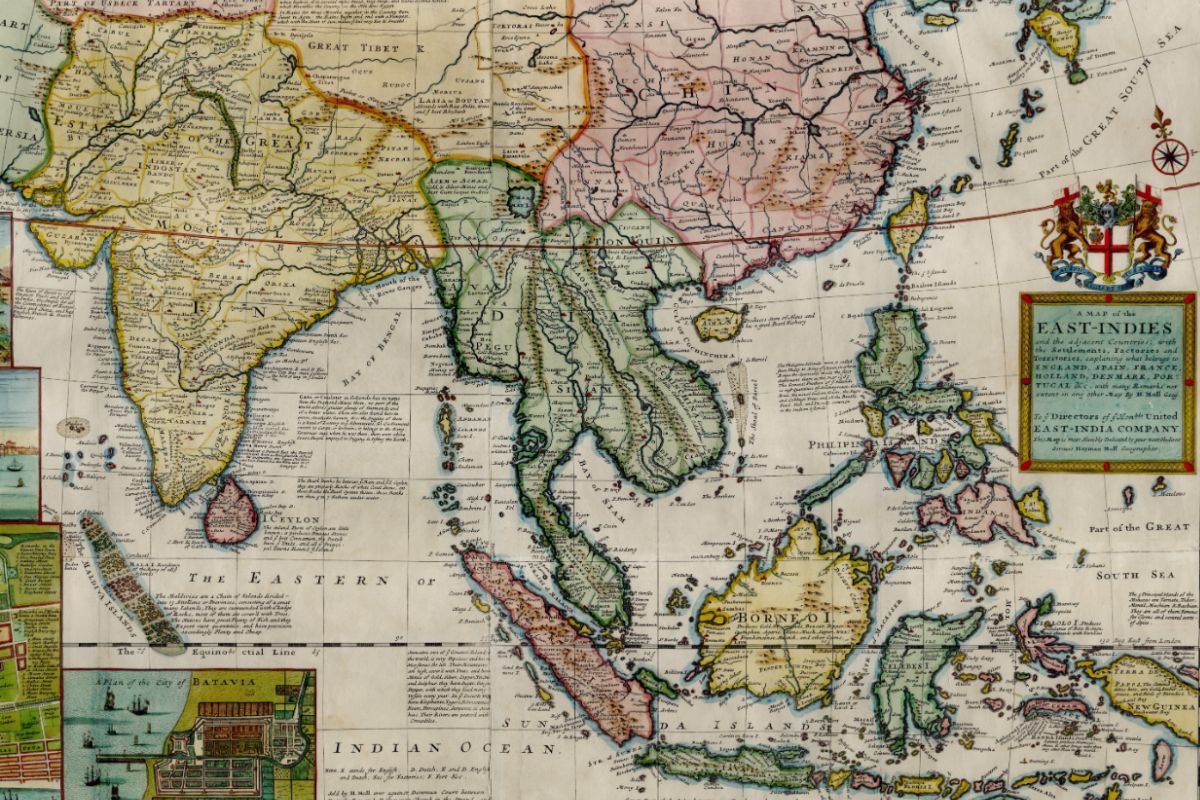

Inspired by the profits Dutch merchants were making in the spice trade by utilising the Cape of Good Hope to circumvent trading through the Middle East, the Company sought to make some of the same riches.

The Elizabethan state wanted to outsource its colonial activities to merchants like the East India Company in order to avoid the risk of losses. Other examples of this are the Royal African Company which ran slaving ships and the Hudson’s Bay Company which imported furs from North America.

Being one of the first joint-stock companies, the Company could gather money for its expeditions more easily and in larger sums, having tradable shares that it could sell on the open market to any number of investors.

As a result, the East India Company was soon granted the Royal Charter: a monopoly over trade in the East Indies.

After realising they had missed the boat when it came to the spice trade with Indonesia – which was thoroughly under Dutch and Portuguese control – the merchants of the East India Company turned to what they hoped would be the next big money maker: the textile industry, and India.

17th Century India

In 1600, the Indian subcontinent made up a fifth of the world’s population and was an economic powerhouse, with trading relations all over the world.

The work of economic historian Angus Maddison estimates that India single handedly produced up to 25 percent of world GDP at the time, towering over England’s measly 1.8 percent.

Much of this wealth came from its textile industry, which was world-leading. The East India merchants could see the potential for immense profits in trade with the highest quality Gurjarat cotton, muslin, and silks.

Yet the subcontinent already had an extremely powerful and wealthy ruling class in the form of the Mughal empire, and its own long-standing system of property relations.

In 1608, the East India Company was granted permission to establish a settlement in Surat (Gujarat), and over the next fifty years it gradually established more trading posts along the subcontinent’s coast.

The arrangement that was made with the Mughal empire boiled down to allowing the Company to have a monopoly on trade in certain areas, in exchange for a tribute being paid.

This suited the Mughal princes very well for a long time. The trading network and infrastructure that the Company provided increased the overall volume of the empire’s trade, while cutting the Mughal’s administrative costs, making them richer for less.

However, as time went on more regional governance was passed over to the Company, with them gaining responsibility for the collection of taxes and tributes from local villages.

In 1661, after the restoration of the monarchy in England, Bombay (Mumbai) was also granted to the Company to govern ‘in trust’ on behalf of the English Crown, after it had been gifted to them by Portugal.

This marks the beginning of its transformation from just a merchant company to a governing, military body, and an arm of the British state overseas.

Empire-building

From the beginning, there had been many threads tying the East India Company to the British state and ruling class.

Beyond having the Royal Charter as an official state sanctioning of their activity, many members of Parliament also had shares in the Company.

This relationship only grew closer over time. Before long there was a revolving door between the positions of ‘East India trader’ and ‘Member of Parliament’, and into the 18th century the parliament began to back Company control in India with state power.

The position of the East India Company in the subcontinent was also heavily shaped by a shifting balance of geopolitical forces, globally and regionally.

The ongoing conflict between England and France during the 17th and 18th century played out in various locations across the globe, including in India. The Carnatic wars charted the struggle for dominance between the French East India Company and British East India Company.

However, the role played by the East India Company was also shaped by developments within the Mughal empire, which since the start of the 18th century had entered into a period of decline.

Although the Mughals had successfully maintained control over much of the subcontinent for several centuries, this was hard won. Following the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, under whom the empire’s territory had expanded to its high point, cracks began to form.

Divisions amongst the nobility, discontent within the military, peasant rebellions, and an increasing regional independence all contributed to the erosion of the empire’s once-solid base over the next few decades.

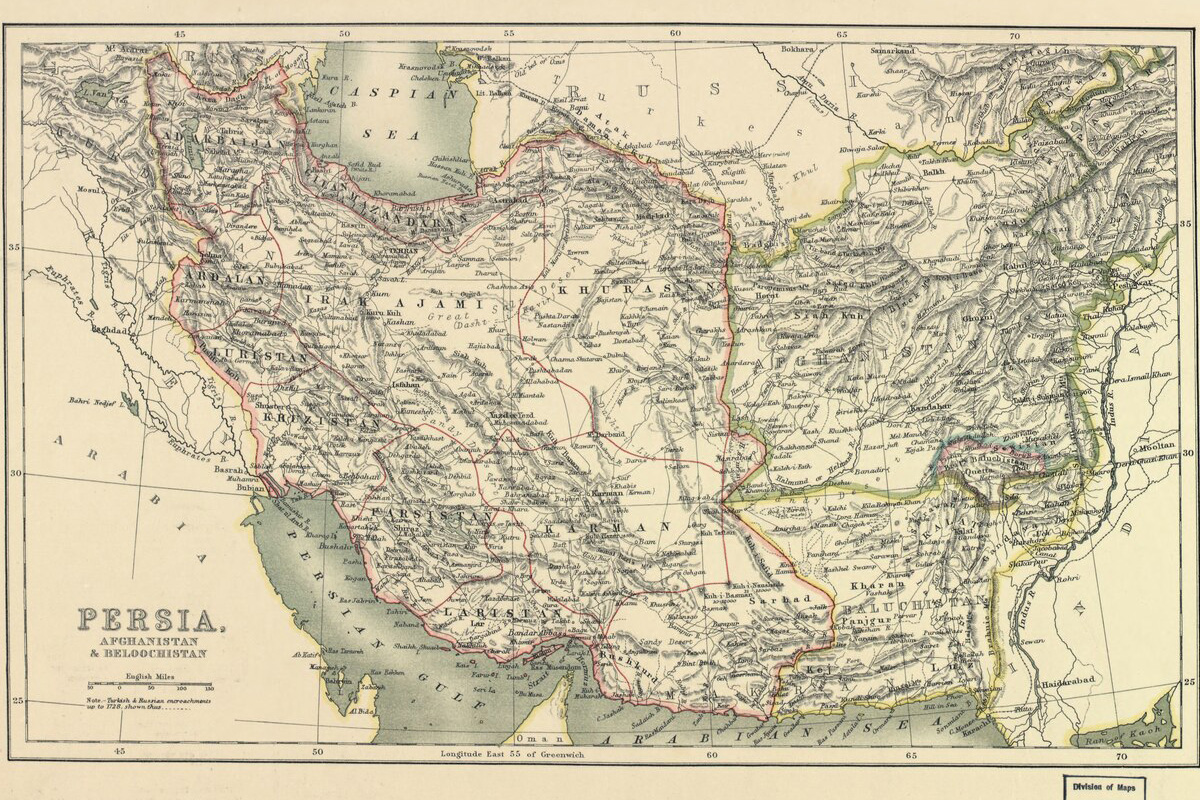

Sensing weakness, regional competitors – the Maratha, the Persians, the Afghans, and so on – looked on with interest, hoping to increase their own territories.

This came to a head in 1739 when Persian commander Nader Shah, fresh off of conquering Afghanistan, arrived to seize Delhi. What followed was arguably one of the most astounding military feats in history, and a death knell for the Mughal empire.

Festering splits and disarray in the Mughal army put its two principal generals at odds at this crucial moment, while Nader Shah was a tactical genius leading disciplined, unified troops. The Persian army also had access to the latest military technology, against the Mughal’s antiquated weapons and tactics.

In just a few hours, Nader Shah and his 100,000-strong army defeated the 300,000 Mughal troops present, and proceeded to plunder Delhi, seizing almost all of the Mughal’s riches, including the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Without the backing of its wealth, the Mughal empire rapidly began to disintegrate and fracture.

One consequence of this was that no one could stop the French and English trading operations from – as they had long desired – militarising to secure and increase their dominance.

Company Rule

Unease and discontent developed among the ruling class of India with the East India Company in the following decades.

With its own burgeoning military, the Company had become a genuine threat to the authority of the princely families and hereditary regional rulers.The regional governor of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah, suspected the Company was also hiding away a great deal of wealth and treasures by consistently misusing their trade privileges.

After the Company refused his order to tear down unauthorised fortifications in Bengal, Siraj laid siege to Kolkata in 1756. This led to the Battle of Plassey a year later when the Company retaliated.

Despite the backing of French forces looking to strike a blow against Britain, Siraj was betrayed by his own court, who defected to the Company’s side, and defeated.

This marked the beginning of the period of ‘Company Rule’ in India. The East India Company now governed the majority of the Bengal region, having installed a puppet government to ensure the state would not get in the way of its, or any of its allies, profits.

The floodgates were open for capitalism to enter the subcontinent, and for the crimes of the British Empire to consume the people of India.

In earlier years of the East India Company, its main wealth within the textile industry was through facilitating the import and export of textiles that were produced through labour-intensive, cottage industries across India.

In Britain, labour productivity was the same, yet wages were higher, and so it was not possible to undercut the Indian textile industry.

During the industrial revolution, however, inventions such as the spinning jenny had been developed. This allowed for much more cloth to be produced by one worker, and the British textile industry erupted.

To ensure its success, the East India Company aided the destruction of the Indian textile industry by utilising their favourable trade agreements to flood the market with cheap British textiles, while imposing tariffs on imports of Indian cloth.

‘England began with driving the Indian cottons from the European market; it then introduced twist into Hindostan, and in the end inundated the very mother country of cotton with cottons,’ as Marx explained.

This decimated the Indian village system, which was a system of municipal organisation based on a hereditary division of labour. This had been the bedrock of Indian society for generations.

As part of the multitude of industrial developments taking place in England, the military technology of England had become far superior to any other power in the region.

This was one factor in the victory of the Battle of Plassey, which also operated as an outward-facing show of strength, pushing aside other European colonial powers in South Asia (namely the Dutch and French) to pave the way for the British Empire.

The Company was no longer simply a trading corporation, but could now operate as a private mercenary group as needed.

At the Battle of Buxar in 1764 regional powers in India sought again to push back against the Company’s expansion, but lost. The battle concluded with the Company signing a treaty which transferred to them the Diwani of Bengal, giving them the right to administer land tax.

Nine years later, the Company made a deal to gain legal powers in the region. This amounted to them being handed full sovereignty of Bengal.

1770 Bengal Famine

Before the English merchants arrived, while the Mughal empire had certainly brutally exploited the peasant communities, they had overseen a social function.

The princes and princely families maintained collective works like water irrigation, and mitigated disasters like crop failure, providing food and aid when needed to avoid the starvation of the population.

However, the East India Company had been very clear that they did not see their role as a social one – ideas of Britain’s role being one of ‘nation building’ and ‘civilising’ came later, during the Victorian era and the British Raj.

The Company was governing the region in order to better extract profits from it.

The methods of British domination were reliant on racism and brutality. ‘Torture formed an organic institution of its financial policy,’ Marx said at the time, with methods to collect taxes, for example, including suspending people from trees and searing them with hot irons.

For the Company, these taxes were primarily collected not to improve daily life, but as funds to buy cotton from peasants to sell at massively steeper prices on the international market.

Likewise, they used many acres of farmland to grow poppies for opium that they could send for a tidy profit to China, rather than to grow crops to feed the Indian peasants and workers.

The negligence of the East India Company is most brutally demonstrated by the Bengal Famine of 1770.

In 1768 and 1769, the region’s monsoon failed, resulting in the failure of rice crops. As a natural occurrence, the state had handled this in the past by the emperor waiving taxes and regional administrators providing soup kitchens and aid.

The British imperialists did not understand or care about this. Their complete neglect of all public works led to an increasing occurrence of all the ‘natural disasters’ of famine, drought, and disease in the region.

During the Bengal Famine, the Company continued to export rice and grain, with no attempt to distribute food in starving communities. They also continued to collect tax despite the devastation.

In places where there was still some princely family control there was food given out, but in Kolkata, which was fully Company owned, not one soup kitchen was opened as famine relief.

Human bodies were lining the streets, being eaten by vultures and dogs, but the Company still sent soldiers into the villages with bayonets to take their taxes by force. Hundreds were hanged for nonpayment.

In 1772, the East India Company shareholders found a hundred percent of the expected tax had been collected – this news was received happily, and with full knowledge of the scale of devastation taking place in India. In response the shareholders voted to increase their dividend from 10 percent to 12.5 percent.

Ultimately, it is estimated that between two million and ten million – between a fifth and a third of the entire population of the Bengal region – died as a result of starvation or disease in the 1770 famine.

Parliamentary measures

By 1773, the Company had squeezed all the money it could for the time being from the Indian population, and spent it. There was nothing more for those who had survived the famine to hand over as tax, at the threat of a bayonet or not.

Corruption, expensive wars of expansion, the costs of administering its territories, market instability, and the struggle to keep ahead of its competitors meant that debts had been piling up for some time for the East India Company.

Word was sent to London, explaining that they could not keep up with their debts and asking for the state to bail them out. Deeming the Company too big to fail, the British state bought a fifty percent share to alleviate the immediate concerns.

While the money was rolling in, the British ruling class were content to outsource the running of one of their greatest colonies to a bunch of merchants. But they had come to realise they needed one hand on the wheel to keep the operation on the rails.

This decision sowed the seeds of the future British Raj. Company rule in India had begun to move further under the control of the British government.

The Regulating Act of 1773, followed by Pitt’s India Act in 1784, brought into scrutiny the activity of the East India Company in its governance of India – not for its crimes against the population, but for how it was balancing its books.

By 1803, the East India Company had 260,000 troops, marshalling more firepower than any nation state in Asia and outnumbering the British army by over 100,000.

Over the next half a century, the Company continued to expand the territory’s holdings in India through a series of bloody and costly wars. By 1856 all of the subcontinent south of the Himalayas was ruled either directly by the Company or by allied local rulers.

And yet in the same time period, with each extension of its charter, the Company’s once-total control over trade with and within India was gradually eroded by the British government.

In 1813, for example, Parliament declared that the Crown was sovereign over all of the Company’s territories despite the Company’s political and administrative responsibilities.

As such, it added, it was required to open up India to Christian missionaries.

1857 uprising

The introduction of Christian missionaries to India exacerbated tensions between the Indian population and Company rule.

Tensions were already heightened by a number of factors: the continued ruthless tax programme of the East India Company, the demoralisation in the military after the failed annexation of Afghanistan in 1832, and the ‘doctrine of lapse’ policy.

This policy stated that if a ruler of a princely state died without a male heir, or demonstrated ‘incompetence’ while living, the territory would pass into Company control. This resulted in an accelerated annexation of India and eradication of the princely families, consolidating the Company’s control.

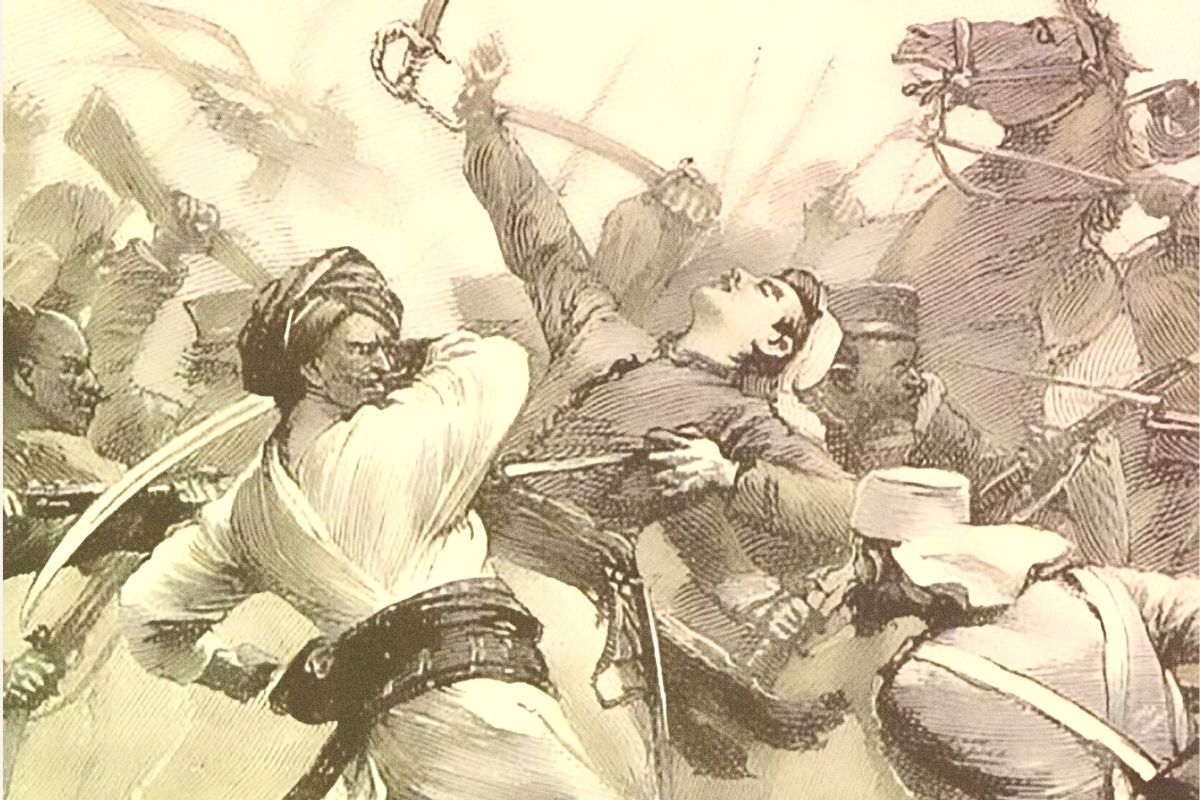

The final straw, however, was the alleged use of cow and pig fat on the bullet casings of new guns, infuriating both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. Sepoy soldiers, peasant soldiers, and aristocracy alike rebelled against the rule of the East India Company, which was an implicit rebellion against British rule.

This uprising started on 10 May 1857 and ended on 20 June 1858 after rebels’ defeat in Gwalior.

This represented a massive challenge to the British empire, with people uniting across religious divides against their common enemy – something that the British did everything in their power from then on to stop from happening again.

The British regained control of the situation through barbaric repression which swept across the country, resulting in some of the most brutal scenes in the history of British imperialism.

Tens of thousands of suspected rebels in the bazaar towns that lined the Ganges were hanged and murdered, and civilians were subject to loot, rape, and torture.

In Delhi, the city gates were locked, and British soldiers were ordered to take no prisoners; every male over the age of sixteen was to be considered an enemy and shot on sight.

Some captured rebels were hanged from trees, others tied to the mouths of cannons which were then fired. Testimonies from East India Company soldiers at the time describe dead bodies rotting in the sun everywhere, and horses slipping in the blood-soaked streets.

End of the East India Company

The same Parliament that had facilitated the East India Company’s rise to power, finally had had enough. The British state stepped in to bring India under the direct governance of the British Crown.

The Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, was tried for treason after supporting the uprising and sentenced to exile in Burma (Myanmar). He died there in 1862, bringing the Mughal dynasty once and for all to an end. In 1877 Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India in his place.

Already in 1859, the governor general, Lord Canning, had formally announced that all of the Company’s Indian assets would be nationalised, passed to the control of the British Crown, and that Queen Victoria would from that point be ruler of India.

The Company had served its historic role, bleeding the Indian subcontinent dry in order to lay down the foundations for British capitalism and then imperialism.

Although the East India Company would stagger on for another fifteen years, in truth this turn marked the exit of this “empire within an empire”, as Burke once called it, from the stage of history – but signalled only the beginning of the crimes of British imperialism in the Indian subcontinent.