“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.”

– Jawaharlal Nehru, Tryst with Destiny Speech, 14 August 1947

These famous words of Jawaharlal Nehru could not have been further from the grim reality. India’s independence took place via partition with what became Pakistan, in which up to two million people were killed, and 80,000 women were abducted, many of whom were raped.

14.5 million refugees crossed the newly formed border, in what was the largest peacetime mass-migration of people in human history. Families were torn apart. People who had lived in their ancestral homes for centuries, were forced to leave based solely on their religious identity.

Partition was not pre-planned, but was the product of many factors: British divide-and-rule policies; the inability of national-bourgeois parties to fight a genuine revolutionary struggle against colonialism; and the failure of the Indian Communist Party to play a decisive role in events.

Divide and rule

Britain first came to India in search of trade and the prized spice market. They established the British East India company in 1600. It grew enormously wealthy and soon began to interfere in Indian political affairs to protect British trade interests. This led to military and territorial claims, most famously with Robert Clive’s victory in Palashi (Plassey) in 1757.

India’s native industry, exports, and independence were destroyed at the behest of British business interests, as Karl Marx noted in 1853:

“It was the British intruder who broke up the Indian hand-loom and destroyed the spinning-wheel. England began with driving the Indian cottons from the European market; it then introduced twist into Hindostan, and in the end inundated the very mother country of cotton with cottons. From 1818 to 1836 the export of twist from Great Britain to India rose in the proportion of 1 to 5,200.” (Karl Marx, New-York Daily Tribune, 25 June 1853)

In 1857, a tipping-point was reached with the great Indian Uprising, later described as the ‘First War of Indian Independence’. The rebellion was triggered by new rifle cartridges – which had to be bitten into to release powder – rumoured to be laced with both pig and cow grease, offensive to both Hindus and Muslims.

The uprising was brutally put down. Company rule ended, and India formally entered the British Empire under direct rule from London. But the event had a profound impact on India’s colonial rulers. They were subsequently careful not to upset religious sensibilities and became acutely aware that unity between Hindus and Muslims could bring down their rule.

As late as 1940, Winston Churchill argued at a cabinet meeting that:

“He did not share the anxiety to encourage and promote unity between the Hindu and Moslem communities. Such unity was, in fact, almost out of the realm of practical politics, while, if it were to be brought about, the immediate result would be that the united communities would join in showing us the door. He regarded the Hindu-Moslem feud as a bulwark of British rule in India.” (War Cabinet Minutes 30 (40) 4, 2 Feb 1940, our emphasis)

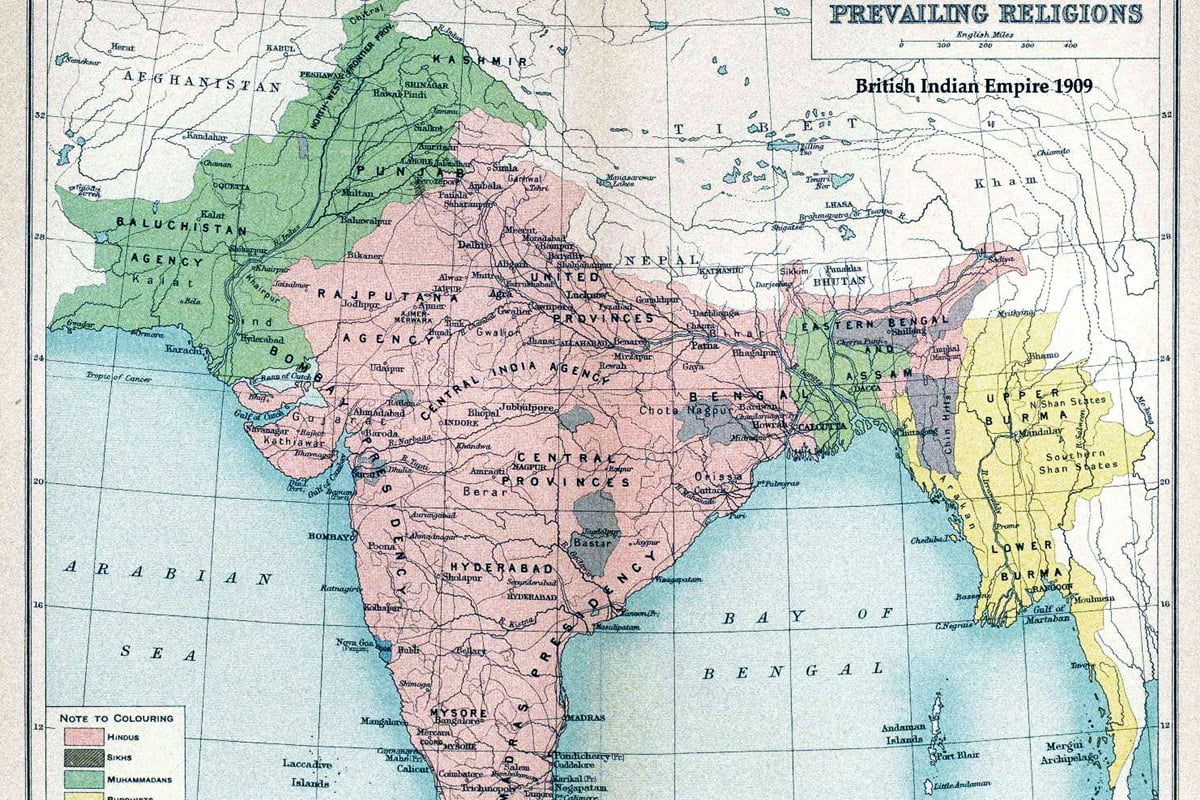

The British tried at every point to foster communal divisions. They officially categorised Indians by monolithic identities of religion, caste, and tribe in census reports, which gave status and hierarchies to communities where previously there had been none. The 1871 Criminal Tribes Act for example made mostly nomadic tribes criminals from birth.

Where communal violence did break out, police would stand back and be slow to intervene. When Indians jointly protested against the British, however, ruthless violence would be used to put down protesters. The most bloody example was the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919, where up to 1,500 innocent people were killed.

Fear of revolution

In 1909, the Morley-Minto reforms introduced separate electorates and reserved seats for Indian Muslims at the request of a small layer of elite Muslims who wanted to preserve their privileges and status.

The 1935 Government of India Act developed this formalisation of sectarian divisions by dividing the country into separate electorates via religion. This created the illusion of local democracy, whilst all power in regards to defence and external affairs were kept in British hands.

Elections were held in 1937. They only represented between 11-14 percent of the population because they required property qualifications, meaning rural landholders had an outsized say.

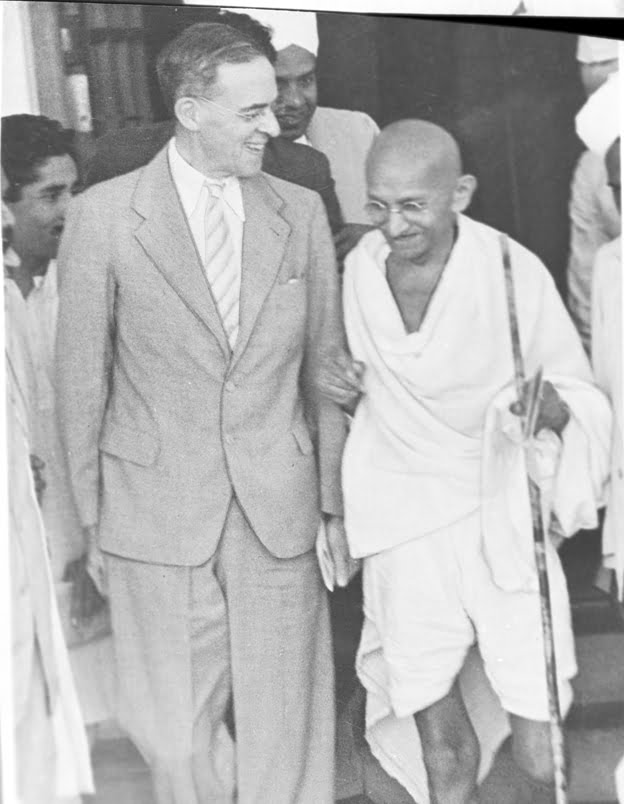

The Indian National Congress party won just shy of half of all seats. The Congress Party was the main national-bourgeois party of India, whose leaders were Mahatma Gandhi, Jawharalal Nehru, Maulana Azad, and Vallabhbhai Patel. It claimed to speak for all Indians. Whilst they did have mass support, their main backers were wealthy Hindu landowners and businessmen.

The Muslim League was the other main bourgeois party. They were utterly trounced in the elections, winning only five percent of the Muslim vote. Their main support bases were in areas which would not go on to become modern-day Pakistan. It was led by Muhammed Ali Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan.

The Indian bourgeois leaders were totally incapable of leading a successful revolution against British colonialism because of their fear of the working class and poor peasants. The native capitalists and landlords were in fact tied to British capital and the City of London.

J.P. Srivastava, an industrialist, told Viceroy Wavell that he and other leading industrialists, mainly Hindu, started financing the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha (a right-wing Hindu revivalist organisation) in 1937. This was because they feared the Congress Party might threaten their profits if put under pressure from the masses.

A revolution which could mobilise workers and peasants (the majority of the nation) against British rule would logically threaten the private property of Indian capitalists and landlords. This explains the fundamental weakness of the Indian nationalist movement.

The bourgeois Indian leaders always accommodated themselves to British divide-and-rule tactics. They accepted offers of round table talks, invitations to the Viceroy’s house in Delhi or Shimla, and the meekest reforms.

The Indian bourgeois leaders did not fight for independence. Instead, they fought for a negotiated settlement in the backrooms of Delhi, Shimla and London.

The ‘Pakistan’ demand

India was a patchwork of religious groups, ethnicities, and castes. There were no clear monolithic religious or cultural identities, despite the British rulers’ best efforts to divide and rule.

The idea of Pakistan initially appealed to wealthy and elite Muslims, especially after the Muslim League’s terrible performance in the 1937 election.

Jinnah’s response was to transform the Muslim League, whip up communal feelings, and warn Indian Muslims that Congress was a totalitarian Hindu party. His transformation into a mullah held a great degree of irony. Jinnah was the perfect English gentleman, wore English clothes, ate pork, drank whisky, spoke aristocratic English, and barely knew any Urdu.

The real reason Jinnah whipped up communal sentiments was to preserve the interests of elite Indian Muslims to land, government positions, and privileges.

In March 1940, the All India Muslim League adopted the Lahore resolution, widely regarded as the ‘Pakistan demand’.

1942: beginning of the end

In the last years of the British Raj, what became clear was that only when the Raj faced imminent danger of overthrow did the British rulers offer any serious concessions towards independence.

In 1942, for example, British colonies across South East Asia were toppling. Hong Kong, Singapore, British Malaya, and Burma all fell to the Japanese. The Japanese imperial army was right on the doorstep of the Raj.

The War Cabinet in London reluctantly sent out Sir Stafford Cripps to offer future independence after the war, in return for continued support for the Empire during the war.

Importantly, a provision was included that any province which wanted to secede, could. It can therefore be said that, as early as 1942, the British considered the partition and balkanisation of India.

Talks failed, with contradictory messages sent from the War Cabinet and Cripps.

The cynical Cripps Mission only compounded the simmering convulsions within India. There were price rises, the Japanese on the border, and refugees from fallen British colonies telling stories of devastation.

Indian capitalists vacillated, sensing that the Raj could collapse. At this moment, Gandhi, for the first time in his political career, launched a ‘do or die’ nationwide uprising against the British to ‘Quit India’.

Beginning in August 1942, this was the gravest threat to the Empire since 1857. Up to 100 army battalions were needed to quell the uprising with brute force. Torture, rape, and mass fines were all used. Official statistics reported 91,836 arrests and 1,060 killed. 208 police stations, 332 railway stations, and 945 post offices (all symbols of colonial power) were destroyed or severely damaged. 216 policemen defected.

The Bengal famine of 1943 went on to kill approximately three million people, as the War Cabinet in London refused food relief.

Subhas Chandra Bose, the former Congress President, went on to form the I.N.A. (Indian National Army) from 60,000 Indian POWs. They fought alongside the Japanese in Burma against the British under the slogan ‘Delhi chalo’.

The British Raj was under siege. It was the beginning of the end.

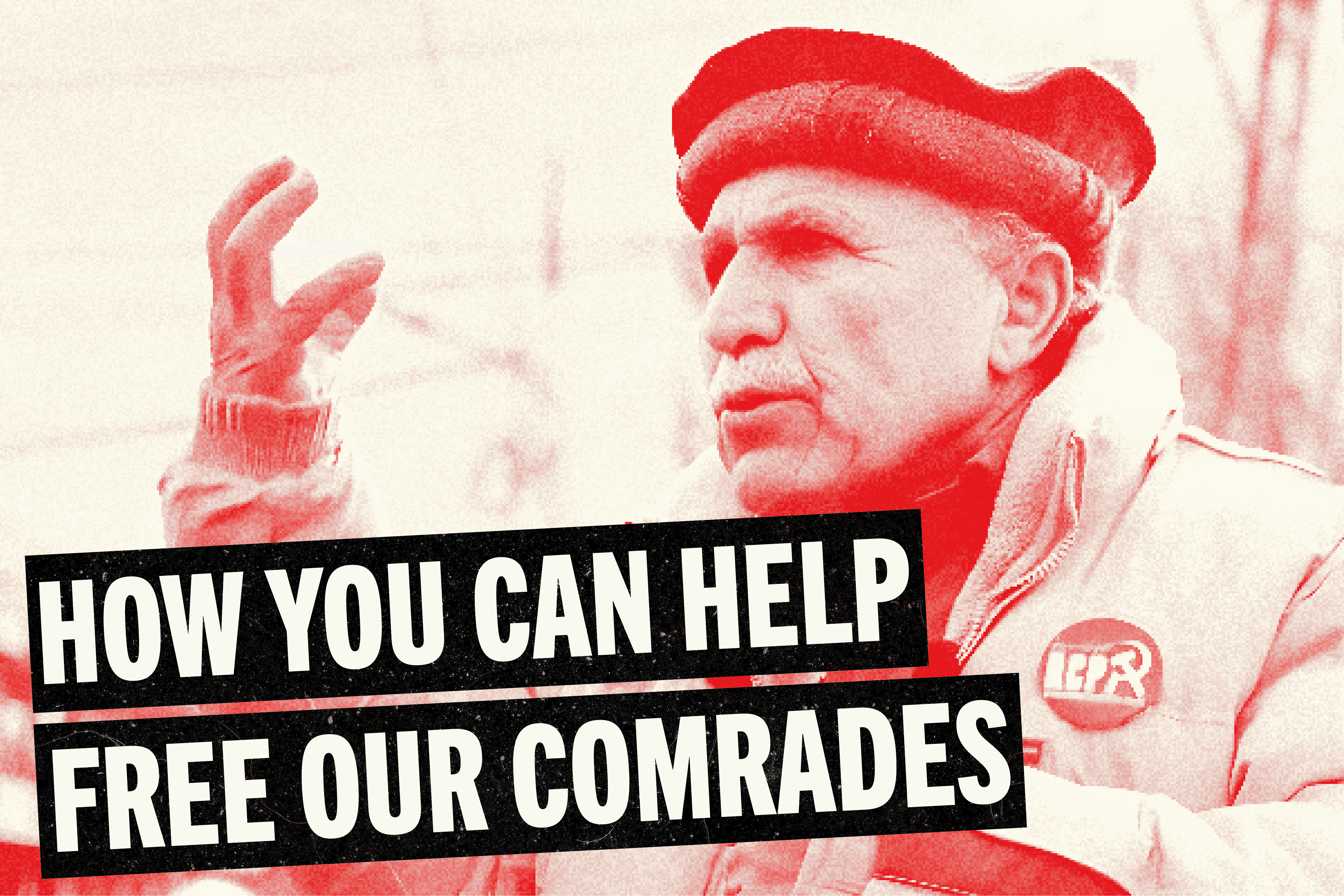

A mention should be made of the Indian Communist Party, who throughout all these tumultuous and historic events gave unconditional support to the British. Initially anti-war, the party U-turned and supported the war after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.

The British rulers even legalised the party for their support in 1942, but they were deemed traitors in the nationalist press. Their U-turns and appeals for a popular front with both the Muslim League and Congress disoriented their cadre base and failed to offer Indian workers an independent class position.

Divide and quit

At the end of WW2, the British understood it would be impossible to hold onto India. Britain was bankrupt, owed India money, soldiers wanted to return home, the Indian army and police could no longer be relied upon, and unrest exuded from every pore of the subcontinent. This reality had to be reconciled with defending Britain’s short-term imperialist interests.

A secret report outlining post-war plans, written by Churchill’s joint chiefs of staff for the War Cabinet in 1945, illustrates their thinking.

The report shares Cold War fears of the Soviet Union potentially invading India and spreading communist influence, especially through the North West. They stress the need to have “An Imperial Strategic Reserve”, meaning British military bases and airfields. Partitioning Baluchistan from the rest of India is given serious consideration. They state in regards to future wars:

“It is of paramount importance that India should not secede from the Empire or remain neutral in war.” (Report on ‘Security in India and the Indian Ocean, IOR/L/WS/1/983. Folio 84)

This explains Britain’s independence offers to the Indian leaders.

In July 1946, ‘Plan A’ was negotiated, which involved a weak central state which only dealt with communications, defence, and foreign affairs (to be de facto controlled by the British). Three autonomous regions would then govern, grouped into two smaller Muslim majority areas and one larger Hindu majority area, alongside further provincial autonomy.

The essence of the offer was clear – keep India divided via religion and Britain would continue to rule through her superior industry, banks, and military.

But the divide-and-rule tactics which Britain had fostered for over a century backfired in their face. No agreement was forthcoming. It was events on the ground which changed the course of events, and left the British to push through ‘Plan B’: partition.

Unrest

The British rulers and bourgeois Indian leaders had to negotiate a settlement, or they faced civil war.

On 18 February 1946, a naval mutiny of Indian soldiers on HMIS Talwar spread all over the country. At its height, 78 ships, 20 shore establishments, and 20,000 ratings mutinied, cutting through communal divides.

The naval strike committee consciously elected both a Muslim and Sikh leader. In Karachi, Hindu and Muslim students and workers supported the mutiny and jointly fought against the police and army.

In Bombay, a general strike of 300,000 workers in support of the mutiny was led by the Communist Party. The British rulers, Congress Party, and Muslim League joined hands to crush the uprising. Vallabhbhai Patel, representing the Congress Hindu right, and Jinnah pleaded for the strikes to end. Gandhi condemned the action, declaring:

“A combination between Hindus and Muslims and others for the purpose of violent action is unholy.” (Sumit Sarkar, Modern India (1989) p. 425)

This mutiny directly triggered the Attlee Labour government to send a Cabinet delegation to India to offer independence in the form of their Plan A.

Unprecedented unrest continued whilst negotiations in the backrooms were taking place. In April, police strikes occurred in Delhi, Bihar, Malabar, Dhaka, and the Anadamans. The summer brought all-India railway strikes and nationwide postal strikes. Overall, two million workers went out on strike during 1946 and 12,717,762 working days were lost.

The events clearly illustrated that the communal divisions could be overcome at the barricades in a revolutionary movement to oust the British rulers once and for all. But the Indian bourgeois leaders refused.

Impasse

The pawns of the British rulers, Nehru and Jinnah, instead fostered communal violence as frustrations grew at the negotiation table.

Nehru became Congress President and scrapped Britain’s Plan A for a weak central state.

Jinnah, who had been largely happy with Britain’s communal plan, was furious and launched ‘Direct Action Day’ for Indian Muslims on 16 August 1946. This call-to-arms initiated mass communal violence in Calcutta, which then spread across the country. At least 10,000 people were killed in a curtain raiser for partition.

What came to be known as the ‘Calcutta Killings’ of 1946 cemented hatred between the Muslim League and Congress. They hated each other more than their British rulers. But they jointly feared the masses and a revolutionary uprising even more. This led to an impasse.

By 1947, the British rulers were fed up with the Indian leaders and understood they were losing control of the situation, with both labour unrest and communal violence spreading. To cut across the revolutionary mood and protect its interests, drastic measures were taken.

Partition

In February 1947, Clement Attlee announced Britain would leave India no later than June 1948, and Viceroy Wavell was sacked in place of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the King’s cousin, who was given free-reign to get the job done.

With Plan A at loggerheads, the British resorted to implementing plan B. Initially Mountbatten offered the complete balkanisation of India with every province and princely state able to succeed and become independent. This was fiercely rejected by both Jinnah and Nehru.

The second option offered was the only one left: partition. On 3 June 1947, Nehru and Jinnah sealed the deal.

The British wanted none of the blame for what was to come; hence in June 1947, the transfer of power was brought forward a year to August 15, to a matter of weeks later. Sir Cryril Radcliffe, a man who had never been to India, was flown in to draw the partition line. He was only given five weeks.

Pakistan was granted independence on 14 August, and India on 15 August. Yet, the border was not announced until two days later!

The result was an absolute bloodbath. The uncertainty of where the new border fell led to extreme religious violence and ethnic cleansing by armed communal gangs, in order to secure the border for each nation based solely on religion.

This uncertainty, resulting from Britain’s botched exit, greatly exacerbated all the communal tensions to the extreme.

Britain to blame

India, like the former British colony Ireland, was left partitioned along communal lines, created and fostered by British colonialism. As in Ireland, the British unleashed a Frankenstein’s monster of communal hatred among people who had previously lived together in relative harmony.

Since partition, the two nuclear armed nations have had three wars, with multiple military skirmishes and terrorist attacks. In both countries, religious minorities have been persecuted and left as second-class citizens.

British imperialism bears the ultimate blame for this calamity. Throughout, Britain fostered communal divisions which, once unleashed, produced a logic of their own.

The imperialists’ hypocritical statements about minority rights, at their heart, were a fig leaf to hide their real intentions: the preservation of colonial rule. The design of every inch of authority handed over to Indians had religious division at its core.

The history of partition illustrates graphically how these divisions can be overcome at the barricades through militant class struggles, mutinies, and mass uprisings of the people against their common oppressors.

Revolutionary class struggle respects no borders; it cuts through all religious and sectarian barriers.

That is why we must fight for revolution and a Socialist Federation of South Asia – as the only way to undo the crime of partition.

Timeline

1600 – British East India Company founded

1757 – Battle of Palashi (Plassey), where Robert Clive led the East India Company forces to a decisive victory establishing control over Bengal

1857 – First War of Indian Independence. This leads to an end of company rule and the formal establishment of India into the British Empire.

1909 – Separate Muslim electorates granted under the Minto-Moreley Reforms

1919 – Jallianwala Bagh massacre

1920 – Non-Cooperation movement

1925 – Founding of the Communist Party of India

1928 – Simon Commission Protests

1935 – Government of India Act introduces devolution of local affairs to Indians

1937 – Provincial elections. Congress wins a majority with the Muslim League and Jinnah winning only 5% of the Muslim vote

1939 – Outbreak of WW2. Absolute British rule was established again for one last time.

1940 – Jinnah’s Lahore Resolution

1941 – Communist Party of India changes policy from anti-war to supporting the British war effort

1942 – Cripps Mission, Quit India movement, Indian National Army founded

1943 – Bengal Famine, which killed an estimated three million people

1945 – Labour government comes to power. Congress leaders released from jail. Indian National Army Trials

1945/6 – Provincial elections where Muslim League win large swathes of the Muslim vote

Feb-Mar 1946 – Indian Sailor Mutinies, mass general strikes in Bombay

1946 – Plan A agreement between Congress and Muslim League for a loose united federation of India with a weak centre

Aug 1946 – Muslim League ‘Direct Action Day’ (Calcutta Killings)

Feb 1947 – Clement Attlee announces British will leave India no later than June 1948, and Louis Mountbatten appointed Viceroy of India

June 1947 – Congress and Muslim League leaders agree final plan for partition, and Mountbatten brings forward the date of partition from June 1948 to 15 August 1947

8 July 1947 – Sir Cyril Radcliffe arrives in India to draw the partition line

14 Aug 1947 – Pakistan granted independence

15 Aug1947 – India granted independence

17 Aug 1947 – Partition border announced publicly