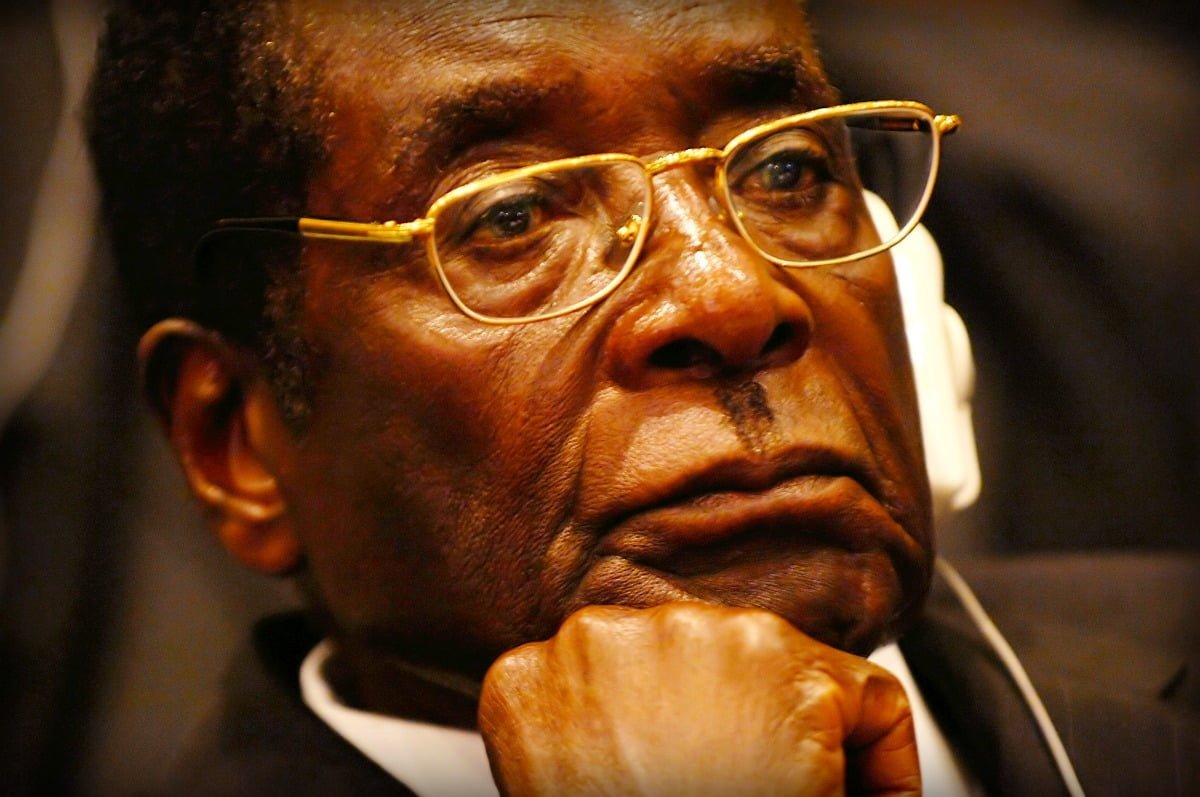

Over the last few weeks, the southern African country of Zimbabwe has experienced escalating protests that have shaken the Mugabe regime to its core. Ben Morken reports on the strikes and militant protests that demonstrate the pent up anger in the depths of Zimbabwean society.

Over the last few weeks, the southern African country of Zimbabwe has experienced escalating protests that have shaken the Mugabe regime to its core. Sporadic protests have broken out because of a severe shortage of cash. These protests have increased in intensity. Dramatic scenes have played themselves out as workers, civil servants and small traders took to the streets to protest against the latest crisis. This culminated in a national stay away on 6 July by public sector workers who have not received their wages for June.

The spark to the latest crisis was an announcement by the government that it has run out of US Dollars which is the currency most commonly used in the country. As a result of this, the government could not pay its obligations in June including wages which makes up to 80% of government expenses. The country is virtually shut off from the international lending markets and foreign direct investment has dried up as the economy teeters on the brink of total collapse. The government is currently in talks with the International Monetary Fund to secure a $986 million loan. Since Zimbabwe does not print its own money the IMF calls for an “internal devaluation” by demanding that the government slash the wages of public sector workers by 20%.

The crisis is so severe that the government also postponed the payment of wages of the army and security services by two weeks. This put into context the severity of the crisis for a regime which is so heavily depended on state repression.

On 17 June the authorities introduced import restrictions on a range of goods in a desperate attempt to force people to buy locally. The effect that this will have on small traders is not hard to see. The formal economy has been shattered and unemployment stands at more than 80%. Many Zimbabweans make a living as informal traders by buying goods in South Africa and selling them in Zimbabwe.

The imposition of import controls was the final straw which broke the camel’s back. On Friday, 1 July, mass protests erupted at the Beitbridge border on both the Zimbabwean and South African sides. On the Zimbabwean side, furious traders marched on the warehouses of the Zimbabwe Revenue Association which have confiscated imported goods from South Africa. After a standoff, demonstrators overwhelmed the authorities and burned a warehouse to the ground. The government responded by deploying the army.

On the South African side, protesters blockaded the border with vehicles and burning tyres. Shops were closed and business activity in the border town of Musina came to a standstill as thousands of people marched on the border. The border blockade effectively also shut down trade between South Africa, Zambia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Malawi.

The protests spread to the capital Harare over the weekend. On Monday 4 July, transport workers came out on strike against police harassment. They explained that police uses roadblocks as a means to demand bribes from minibus taxi drivers. They also demanded that corrupt police officers who fleeced them of their money at the roadblocks be arrested. The workers blockaded roads with their vehicles and with burning tyres in the city centre. This brought traffic to a standstill. Protests spread to Zimre Park, Hatfield, Ruwa, Epworth and Mabvuku. The police responded by arresting 30 people and by firing tear gas and water canons at the workers. But the tables were turned when workers retaliated by throwing stones at the police and beat them up with sticks and stripping them of their uniforms. Soon the police were outmatched and were forced to retreat.

Protesters then marched on a luxury hotel in central Harare where Vice president Phelekezela Mphoko had been staying for more than a year. This is a clear example of the massive gulf which exist between ordinary Zimbabweans which are suffering at the hands of a depressed economy and the leading members of the government which are living in obscene wealth.

In Bulawayo, the second biggest city, taxi operators also decided to blocked the roads to protest against police harassment.

The next day workers in the public sector, including nurses, doctors and teachers came out on strike because of unpaid wages. At the country’s two biggest hospitals, Parirenyatwa and Harare Central, nurses and junior doctors went out on strike, forcing the hospitals to treat only patients which are in a critical condition. The government has said it will pay doctors and nurses their June salaries on 14 July and the teachers on 7 July. The head of the Zimbabwe Hospital Doctors’ Association, Fortune Nyamande, responded by saying that in such a case the strike will then continue until 14 July! Teachers also responded massively to the call to strike with only headmasters, which are not allowed to strike, reporting for duty in most cases.

On Wednesday 6 July, the country was crippled by the biggest mass stay away and a general strike since 2007. Shops were closed and the streets of Harare and Bulawayo were deserted and the bus ranks were empty as workers joined the national shutdown. Protesters set up barricades of burning tyres at entrance points to the center of Harare. The government tried to restrict internet access and especially the Whatsapp messaging service but people found numerous ways to circumvent this including using proxy and VPN services like Tunnelbear. To the chagrin of government censors, pictures of empty streets soon flooded social media.

Because of the nature of the protest – a stay away rather than marches and demonstrations – the day was relatively peaceful. Only in Mufakose in the west of the capital were there clashes as hundreds of young people erected barricades with burning tyres. Unable to crack down on the deserted streets, the police targeted journalists by detaining them and ordering them to delete images.

Ever since the 1998 crisis of hyperinflation, Zimbabwe have used a chaotic multi-currency system including the South African Rand, the US Dollar, the Euro, Australian Dollar and the Chinese Yuan to replace the Zimbabwe Dollar. But recent statements by the Zimbabwe Reserve Bank governor John Mangudya that the bank will start to issue “bond notes” with the same value as the US Dollar have sparked outrage among ordinary people who still remember the nightmare of hyperinflation.

The announcement by the Reserve bank to print the bond notes sparked fears that the US Dollar might no longer be withdrawn from banks and will soon only be available on the black market. Long queues started to appear at banks as people want to withdraw the US Dollar, prompting the government to restrict the amount that could be withdrawn to $1000.

The government tried to get out of the crisis by trying to improve its exports and cut down on imports. But as we have seen, this is only exacerbating the crisis. The country has a severe balance of payment crisis. In 2014 its exports were $2.5 billion and its imports were $6.25 billion, a negative balance of $3.4 billion. This is a tragic turnaround from a country which used to feed the entire Southern Africa. The effects of the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Programmes which were faithfully implemented by Robert Mugabe for the first two decades of his rule together with the economic and political zig-zags from the Mugabe regime after these measures devastated the country, means that it now have to import everything from sweets to toothpicks.

These events come at a sensitive time for the regime. Fierce battles have broken out within the ruling Zanu-PF party to choose a successor to the 92-year old Mugabe. Two clear factions have begun to form between those elements supporting Mugabe’s wife, Grace, and those supporting veteran party member Emmerson Mnangagwa. Grace Mugabe has been at the forefront of purging leading Zanu-PF members including the former vice president Joice Mujuru from the party. Mnangagwa is largely supported by veterans from Zimbabwe’ liberation war.

These splits in Zanu-PF have not been to the benefit to the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) which is also split. Instead, the crisis which have been building up have been expressed outside of the two main political parties. Instead, the movement have been channeled through the #ThisFlag movement which was started accidentally by Pastor Evan Mawarire who posted a video of himself wearing a flag of the country around his neck and complaining about the dire state of affairs on social media. Within hours the video went viral on social media with thousands of people, draping the national flag, posting videos of themselves with describing their own dire circumstances.

The #ThisFlag social media phenomenon soon attracted thousands of activists who took to twitter and Facebook to successfully plan and organise the national stay away on 6 July. However, although it is true that the campaign has been organised largely on social media, the fact that public sector workers were organising themselves through their unions at the same time, greatly enhanced the mobilisation capacity of the movement. In the last analysis, this is the secret behind the successful shutdown.

The #ThisFlag campaign has proven to be a big success in helping to mobilise for the national shutdown. However, there are certain weaknesses which have to be overcome if the campaign is to have long term success.

The first question has to be asked is after shutting down the economy is “what next?” Mawarire has said he is not pushing for revolution or regime change. Instead, he wants to remove the fear that keeps Zimbabwe’s citizens from speaking out, to give them the space to confront their problems and hold their government to account (The Guardian 26/05/2016). It is clear that Mawarire is a well-meaning individual who did not consciously plan to set in motion a national movement which have shut down the economy.The government seems to take the situation very seriously if one takes into account the amount of energy leading members of the government like Jonathan Moyo spends in attacking and ridiculing pastor Mawarire. What the government is afraid of is not so much pastor Mawarire, who is an accidental figure, but the forces he has conjured up. The fact that so many ordinary people have responded to the campaign is indicative of the pent up frustrations and anger in the depths of Zimbabwean society. The stayaway is a serious warning to the regime that the anger in society is reaching a critical point.

But after the shutdown the focus will remain with the public sector workers which are the key to the situation. With the government severely short of cash and desperate to secure the loan from the IMF, the jobs and conditions of thousands of public sector workers are on the line. This means that the unions must be prepared to escalate the struggle. Evan Mawarire has spoken of a 48-hour general strike if the demands of the movements are not met. This is correct. But the severity if the crisis means that an indefinite general strike is a much more than a distinct possibility. But in the end, not even a indefinite strike will resolve the crisis. Only by overthrowing of the capitalist system can the country begin to solve this nightmare for the people of Zimbabwe.