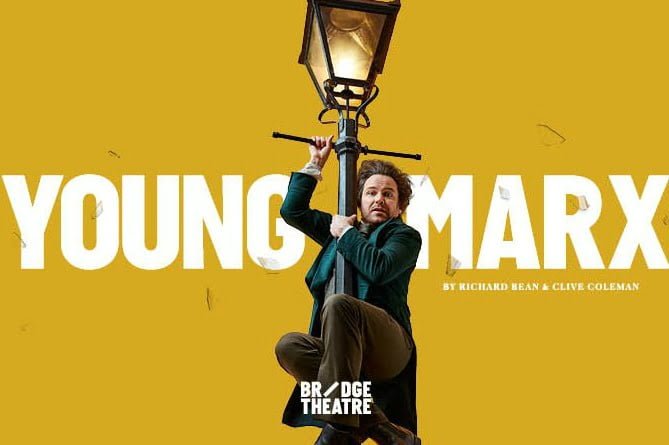

Young Marx is a new comedic play at the Bridge Theatre, set in Soho London, revolving around Karl Marx’s struggle to provide for his family, and fend off spies, creditors, political enemies, and the police, all whilst completing his economic magnum opus, Das Kapital. We publish here a review by members of the Marxist Student Federation, who recently attended one of the first performances.

Young Marx is a new comedic play set in Soho London, revolving around Karl Marx’s struggle to provide for his family, and fend off spies, creditors, political enemies, and the police, all whilst completing his economic magnum opus, Das Kapital.

Written by Richard Bean (writer of the hit show One Man, Two Guvnors) and Clive Coleman (Dead Ringers, Chambers), the play stars Rory Kinnear (Spectre, Hamlet, The Threepenny Opera) as our eponymous hero.

Kinnear plays an animated and fiercely witty Marx, who leaps from explaining how alienation arises from capitalist production whilst cooking breakfast for his family, to explaining the use-value and exchange-value of a solid silver pot he is in the process of pawning.

Sadly, however, the play never makes a serious appraisal of any of Marx’s actual political ideas. Instead, it remains confined throughout to being little more than a series of humorous anecdotes and escapades, loosely based on Marx’s life in London outside of revolutionary politics and writing.

Poverty amidst plenty

The only real success of the play comes in its accurate portrayal of the absolute poverty that Marx and his family were living in at the time. The play opens with Marx’s botched attempt to pawn one of Jenny’s family heirlooms, as Marx clambers over the Victorian rooftops to escape the police.

Their family home is small and cramped, with five to a bedroom, and young “Fawksy” Marx suffering from a terrible fever that would later take his life. Bailiffs are also seen taking away all the family’s furniture and they are reduced to sitting on the bare floorboards until Engels re-purchases it all (plus more) later on in the play.

The play also makes humorous and accurate references to Marx’s love of German music, his disdain for English music, and the infamous 18 stop unfinished pub crawl along Tottenham Court Road.

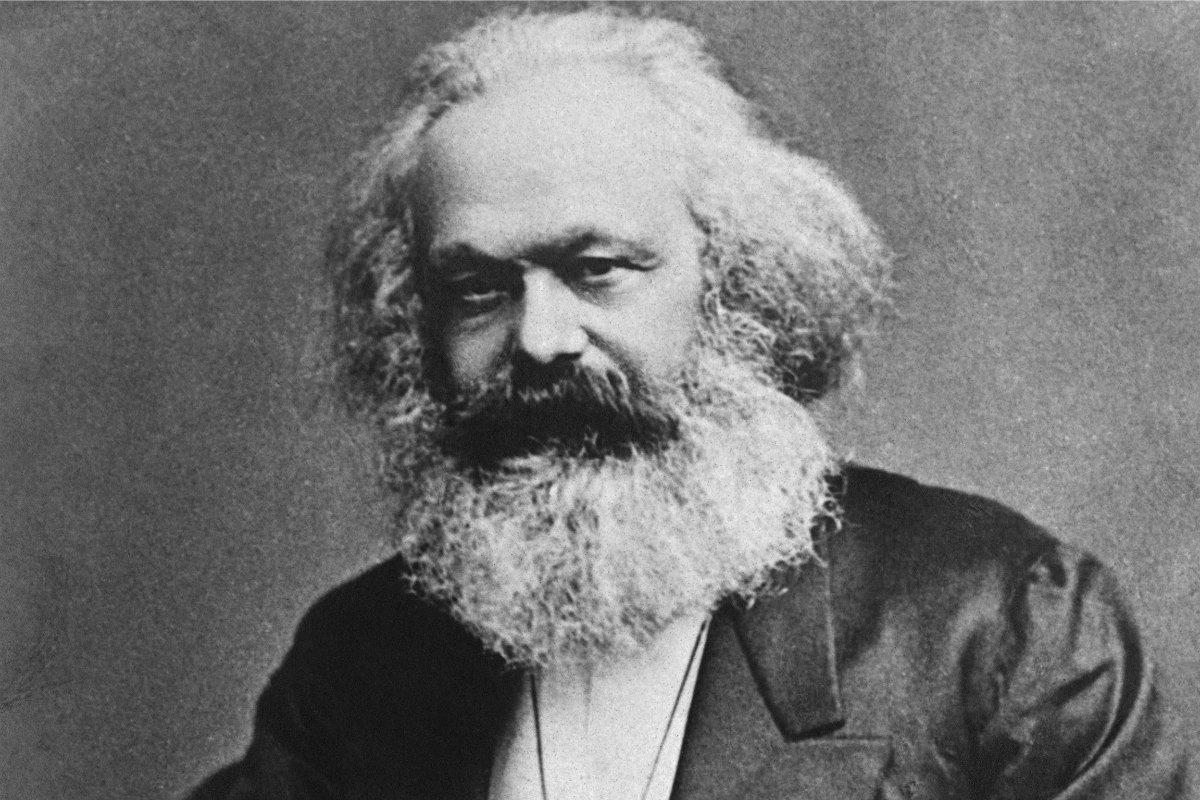

There is also a rather amusing metatheatrical trick in the second half of the play where Marx comes face to face with a remarkably old, white-haired and white-bearded professor in the British Museum. The scene later descends into a slapstick punch up, however, much in line with the overall tone of the play.

The role of Engels

The treatment of Friedrich Engels, here played by Oliver Chris, is arguably even worse than that of Marx. The theoretical brilliance of Engels is completely overlooked, and the play reduces him to a womanising “Cotton Lord” sidekick, who apparently has no meaningful contribution to the cause of revolution other than paying for Marx’s food and drink or berating him, in a rather crude fashion, for not finishing his writings.

The treatment of Friedrich Engels, here played by Oliver Chris, is arguably even worse than that of Marx. The theoretical brilliance of Engels is completely overlooked, and the play reduces him to a womanising “Cotton Lord” sidekick, who apparently has no meaningful contribution to the cause of revolution other than paying for Marx’s food and drink or berating him, in a rather crude fashion, for not finishing his writings.

The real revolutionary life and ideas of Engels are nowhere to be found in this play: the Engels who was asked by the Communist League to write the Communist Manifesto; and who wrote such brilliant theoretical texts as the Dialectics of Nature, Anti Duhring, and Origins of the Family Private Property and the State. Instead we see an Engels devoid of any theoretical intelligence, who spends more time chasing women and drinking than participating in revolutionary activity.

It is a well-established fact that without Engels’ work to finish Marx’s writings after his death, a great amount of these works – including the latter two volumes of Capital – would not even have seen the light of day. Again, this side to Engels’ character is not explored during the play. The only real explicit mention by the writers of any revolutionary activity on Engels’ part is his role “on the barricades” of the 1848 Revolutions.

Where’s the politics?

Whilst it might be expecting too much for a play such as this to be a theatrical hagiography of Marx, it nevertheless had the potential to provide a light-hearted and humorous contribution about the life of a young genius with the weight of the European revolutionary movement on his shoulders.

Instead – although the lewd, tongue-in-cheek humour of the play is quite refreshing at times – the multitude of cock jokes and crass humour is at no point offset by a truly serious appreciation of Marx’s intellect, his political ideas, or his revolutionary activities.

A few quips are made and a few fleeting references are drawn from the Labour Theory of Value, surplus value and wage slavery, along with mentions of Marx’s progression from the influences of Goethe, Feuerbach, and Hegel (a couple of songs are even sung at their expense too!). However, at no point are we presented with a Marx who had the utmost faith in the working class’ ability to transform society and usher in a new era for humankind.

Removing revolution

In fact, for a play that appears to have little to do with the content of Marx’s ideas, the only real political comments are made in two didactic scenes that are clearly intended as direct warnings against attempts at revolution. These unfortunately say more about the opinions of the writers than of Marx himself.

One of these scenes shows a tearful Marx admitting to his nanny Nym (before sleeping with her) that he wished that the martyred “students” of the failed 1848 revolutions had never bothered picking up the Communist Manifesto in the first place; perhaps then their lives would have been saved and the bloodshed avoided – as if to suggest that Marx was unaware of the countless deaths that capitalism had caused and was still causing by virtue of its very existence! It is these very injustices that the workers and middle class revolutionaries of 1848 bravely rallied against.

Marx is also seen at one point to make quite a serious reference to the “danger” of having his (at this point unfinished) economic writings published in Russia, a country where they “eat pickled cabbage and f*** their sisters”. These scenes are not only historically and politically inaccurate, but also serve to undermine any attempts the play makes at satirical comedy, and mar the overall piece as a result.

What better way to dissuade young impressionable revolutionaries than by having Karl Marx himself preach the dangers of revolution!

If the artistic choice was to not deal with the substance of Marx’s ideas, then this decision is completely contradicted by these two scenes alone. The play would have been more consistent without them. It is one thing to avoid the political ideas of the titular character in order to focus more on the personal relationships between the characters, but it is quite another to grossly distort and misrepresent Marx’s revolutionary beliefs.

The Russian Revolution

Marx’s views on Russia were not characterised by a fear and scorn of the millions of oppressed and impoverished Russian peasants. He was first and foremost concerned with the monstrous Tsarist regime (which is conveniently not mentioned in this scene), that “gendarme of European reaction” which kept the Russian masses in its primitive and backwards conditions.

Marx also knew the inevitable limitations of struggling for socialism in a country that had not developed an advanced capitalist economy, like that of Britain and France (this fact is alluded to in the play). His understanding of the historical position of Russia and the tasks ahead of it are shown by his writings about the heroic Narodnik movement, which was a “specifically Russian and historically inevitable method about which there is no reason… to moralise for or against.”Marx never condemned the Russian masses for their backwardness or ignorance, as he knew their time was yet to come.

The inclusion of this scene is blatantly intended as an attack on the Russian Revolution of 1917, and is utterly inconsistent with Marx’s own ideas and perspectives for world revolution. It is not a mere coincidence then that this play debuts in the month of October, almost exactly 100 years since the Russian working class – under the leadership of the Russian disciples of Marx and Engels, the Bolshevik Party – stormed the Winter Palace and established the world’s first workers’ government.

The march of history

Marx’s real attitude and understanding of history is demonstrated clearly by his writings on the Paris Commune, a movement which was premature and had historical forces weighing against it, and which yet was still a glorious episode of working class struggle that he gave his full support to.

Marx’s real attitude and understanding of history is demonstrated clearly by his writings on the Paris Commune, a movement which was premature and had historical forces weighing against it, and which yet was still a glorious episode of working class struggle that he gave his full support to.

The working class did not expect miracles from the Commune. They have no ready-made utopias to introduce par décret du peuple. They know that in order to work out their own emancipation, and along with it that higher form to which present society is irresistibly tending by its own economical agencies, they will have to pass through long struggles, through a series of historic processes, transforming circumstances and men. They have no ideals to realize, but to set free the elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society itself is pregnant.

Revolutionary movements are often limited by the historical circumstances within which they arrive. A leap to socialism cannot be made if the historical and economic basis for it is not in place. However, Marx and Engels knew that facts like this made these class fighters no less brave or heroic, and under no circumstances meant that such movements should be opposed.

Such fear of unnecessary violence and bloodshed is typical of the liberal bourgeoisie, who tremble at the prospect of working class revolutionary movements that are made historically inevitable due the impasse of capitalism. Marx knew better than to bemoan the march of history itself.

The real political differences and conflicts between the communism of Marx and Engels and the Blanquism of August Willich and Emmanuel Barthélemy are barely touched upon. Instead we are presented with Willich’s incessant attempts at courting Jenny Marx, and Barthélemy’s thick-accented buffoonery, and a few questionable remarks from him on the concept of consensual sex in France!

Again, political and historical accuracy are not necessarily pre-requisites to producing an enjoyable play, but one cannot help but feel like an opportunity to explore a rich and exciting period in the history of radical political thought has been squandered in favour of slapstick comedy and penile puns. The same lines of dialogue could have been placed in the mouths of any other historical figures and still have provoked the same response from the audience.

The cause of socialist revolution

It has been said many times that theatre is a place for important questions to be asked, but never answered. Sadly, Young Marx neither asks important questions, nor leaves the audience with anything meaningful to take away, which is thoroughly disappointing given the subject matter of the play.

Young Marx is an enjoyable, humorous piece of theatre with a sharp script and solid performances all round; however, it is not a revolutionary piece of theatre, and has nothing important to say about Marx, the significance of his ideas, or even his own personal life and struggles.

The play is worth watching for a few cheap jokes at the expense of the greatest thinker of the modern world. But if you’re looking for theatre which deals with real questions arising from revolutions and the injustice of capitalist society (the type of theatre we need more of these days), then you may be better off sticking to Brecht or Gorky.

Even better, discover Marx’s wit, humour, and intelligence from the pages of his own works, and join the cause that he fought for (and drank to): the cause of international socialist revolution and the emancipation of humanity.