COVID-19 is bringing economic and social dislocation with no parallel since the Second World War. It is a huge burden on working-class people, and a real concern for the strategists of capital.

World War II had a radicalising effect on the consciousness of working-class people, and ended in revolutions across the globe. Similar conditions produce similar results. The ruling class are nervously trying to learn the lessons from the war experience to avoid a repeat of such radicalisation.

Marxists, too, must study the lessons of war and revolution as a layer of workers move towards radical and even revolutionary ideas in the coming period.

The outbreak of war

World War II was a barbaric slaughter in which, on the pretext of defending the fatherland etc., the ruling classes sent millions of poor and working-class people to die for what was in reality only a defence of the capital of the fatherland. The unimaginable destruction and suffering caused by the war was a direct reflection of the dead-end that humanity faces in capitalism.

World War II was a barbaric slaughter in which, on the pretext of defending the fatherland etc., the ruling classes sent millions of poor and working-class people to die for what was in reality only a defence of the capital of the fatherland. The unimaginable destruction and suffering caused by the war was a direct reflection of the dead-end that humanity faces in capitalism.

Nevertheless, in many countries, working-class people supported the war effort, not in defence of their own ruling class, but as a means of fighting fascism. This was the case in Britain, where the entry into the war was met with cautious support from most layers of the working class, who understood the threat fascism posed to their class.

From 1936 to 1938, not long after Tory politicians and newspapers like the Daily Mail were fawning over fascism in Italy and Germany, thousands of British workers travelled to Spain to fight Franco as part of the international brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Many hundreds of thousands more donated to collections funding the fight against fascism. The working class was ideologically prepared, on its own terms, to fight Hitler.

To the extent that large layers of the working class supported the war at its outbreak, it was mainly thanks to this healthy class instinct, rather than the flag-waving patriotism that was more prevalent amongst the middle classes. The memory of the previous war, which had laid bare the imperialist methods of mass slaughter for profit, lingered in the minds of many workers. They were sceptical about the real aims and motivation of the politicians leading them to war.

In June 1943, Ted Grant of the Workers’ International League wrote an article that recounted a particular episode which illustrates the mood of the working class at the outbreak of the war:

“An instructive episode occurred in the early stages of the war in 1939, before the fall of France. The Stalinists, during their ‘anti-war’ period, launched a campaign in their stronghold in South Wales. They secured a referendum among the South Wales miners on the question of war. This among one of the most militant and class conscious sections of the workers in Britain. A great deal of discontent and uneasiness existed among the miners on the question of the war. They were suspicious of the aims of the ruling class. Under these conditions, the Labour and reformist bureaucrats had to execute a manoeuvre to prevent the Communist Party from gaining big support among the miners on the ballot vote. They placed the question on the following basis: ‘Against the war’ or ‘For the war with a Labour government’. As was to be expected they secured an overwhelming majority of the votes for the latter. And this was at a time when Hitler had not gained his tremendous victories and the masses did not feel directly threatened by the totalitarian heel of the nazis.”

This kind of cautious support also characterises the approach of many workers towards the government’s policies towards the coronavirus today. In fact, many workers have been demanding that the government policy of economic shutdown and social distancing be applied to them, against resistance from their bosses. 93 percent of people polled the day after Boris Johnson announced the UK shutdown of non-essential businesses said they approved of the measure. And for the first time as Prime Minister, Johnson’s approval ratings turned positive.

But to say that working-class people are suspicious of the Johnson government would be an understatement. Boris himself is widely viewed as deeply untrustworthy and shamelessly opportunistic. YouGov polling from December 2019 revealed that 54 percent of people polled felt that Johnson was someone who broke his promises, with just 19 percent saying they would trust him to keep a promise. 60 percent considered him to be a bad role model, with just 16 percent saying that he could be considered a good one.

To the extent that workers support Johnson’s current policies, it is out of a sense of self-preservation, rather than trusting the government to act in their best interests. Just as in 1939, this is a flimsy base of support with which the British ruling class are entering a period of unprecedented economic and social dislocation.

Changing consciousness

As the Second World War progressed, attitudes began to change. There is nothing like asking workers to sacrifice their lives to make them question the legitimacy of the system and the society they are sacrificing it for. The hammer blows of events eliminated all traces of patriotism and opened the way for mass radicalisation. This is in general the case with wars, which tend to open up with a period of national unity but lead to increased class polarisation. This is why war so often leads to revolution.

As the Second World War progressed, attitudes began to change. There is nothing like asking workers to sacrifice their lives to make them question the legitimacy of the system and the society they are sacrificing it for. The hammer blows of events eliminated all traces of patriotism and opened the way for mass radicalisation. This is in general the case with wars, which tend to open up with a period of national unity but lead to increased class polarisation. This is why war so often leads to revolution.

British workers still wanted to defeat fascism, but they were increasingly unhappy about how their government was going about it. The bosses were making huge profits, while workers’ rights were being eroded; the rations were inadequate, and the air-raid protection was sub-standard.

This changing consciousness expressed itself politically throughout 1942 and 1943, during which a left-liberal party called the Common Wealth party stood candidates in by-elections against the all-party coalition government. It succeeded in winning seats in Tory heartlands such as Eddisbury, Skipton and Chelmsford, which rattled bourgeois commentators who used the pages of The Times and other newspapers to warn of the bubbling discontent of the masses.

On the industrial front, the number of strikes in Britain increased year-on-year each year from 1939 to 1944, by which point over 3.7 million working days were lost to strike action – the highest figure for a decade and one that would not be matched for another decade. This was despite the existence of the government’s Conditions of Employment and National Arbitration Order, known as Order 1305, which effectively banned strike action during the war and which was broadly accepted by the trade union leadership.

In 1941, engineering apprentices struck for better pay on the Clydeside, and in Coventry, Lancashire and London. These workers were not unionised, and had little reputation for militant action, and yet they were the first to defy the government and the employers.

In January 1942, a 19-day strike for better pay for harder working conditions by miners at Betteshanger colliery in Kent was met with the prosecution of 1,050 miners and the imprisonment of three union officials. In response, more pits came out in solidarity with the strikers and in the end the government backed down, releasing the union officials and dropping the prosecutions. The miners were key workers for the war effort which, coupled with good organisation and militancy, gave them the power to defend their pay and conditions.

In early 1943, workers at the Neptune ship repair yard on Tyneside struck for six weeks in defence of the ‘closed shop’ agreement, strengthening the organisations of the working class. Engineers in Barrow also struck that year at the Vickers Armstrong yard over the question of pay, which hadn’t risen for 29 years despite the company’s massive profits thanks to armaments production.

The Barrow strike was unofficial, but it had the backing of the local branch of the Amalgamated Engineering Union, which frightened the national union leaders who were trying to maintain an industrial truce with the bosses. Industrial struggles such as this throughout the war caused many workers to criticise, not only the bosses and the government, but also the labour movement leaders.

Also in 1943, workers in the Chrysler factory in London, which had been converted for war production, combined to demand better treatment at work and an increase in the minimum wage, which they won. Many of these workers were women whose husbands were in the army. They saw their fight, as working-class families, unfolding on two fronts – one against the Nazis and one against the bosses taking advantage of the war situation. One of these Chrysler workers said during the dispute: “If I don’t fight for conditions and wages or let them get worse, my husband will kill me when he comes home”.

Those ‘workers in uniform’ who made up the army were clear on which side they stood in the class struggle. In the spring of 1943, in the wake of a strike by Welsh coal miners, the headline of the newspaper produced by the Eighth Army, then stationed in North Africa, was ‘Right to strike is part of the freedom we fight for’. Included in that issue of the army newspaper was a petition to the Home Secretary signed by 82 soldiers in the Royal Engineers protesting the arrest of four Trotskyists. Despite the best efforts of the government and the bourgeois press to pit strikers against soldiers during the war, it was class solidarity that frequently triumphed.

1944 saw 180,000 coal miners strike over pay and conditions in the mines. The industrial minimum wage was £6 10s per day but miners were expected to make do with just £5. On top of that, safety standards had been eroded so far that by 1944 you were more likely to be injured as a miner than in the army.

In response to the strike, and given the importance of coal to the war effort, the government attempted to conscript apprentices from other trades and send them to the mines. This provoked enormous opposition, and by March 1944, 26,000 apprentices were on strike on the Tyne, in Glasgow, Huddersfield and Teesside, demanding an end to the conscription and the nationalisation of the mines. Such was the level of class anger that, whichever way the government turned, it was met by an organised and militant layer of workers ready to break the law to defend their pay and conditions.

The above are just a fraction of the industrial disputes that took place during the war years. It took a couple of years for the fury against the profiteering and mismanagement of the war effort by the capitalist class to find an expression in strike action, and a couple more for this to find its first, confused, political expression. But once in motion, the trickle of industrial disputes soon became a torrent.

Today, we are still in the early stages of this crisis, but already we have heard reports of unofficial action in workplaces around the country over gross violations of the safety of workers. Workers at the Linden Foods factory in Northern Ireland walked out over a lack of social distancing measures at work. Workers at Royal Mail delivery units across the country have walked out over health and safety concerns, with the backing of the Communication Workers Union leadership. Refuse workers on the Wirral and elsewhere have refused to work for the same reason.

Even where action has not yet taken place, a mood of anger among workers is clearly building up. Those who were yesterday treated as unskilled, low-paid and easily replaceable, are now hailed as key workers without whom the country would grind to a halt. These supermarket workers, lorry drivers, and refuse collectors are beginning to realise what a raw deal they are getting and how much potential power they have. Why should the supermarket bosses be reaping mega-profits while their workers are still being paid a pittance? With this crisis, and the changing consciousness it will bring, we have a recipe for intensifying class struggle. The parallels with a wartime situation are striking, in every sense of the word.

From war to revolution

The end of the war revealed the sharp turn to the Left many workers had taken during the conflict. A revolutionary wave swept Europe, with The Economist writing at the time that “The collapse of that New Order imparted a great revolutionary momentum in Europe. It stimulated all the vague and confused but nevertheless radical and socialist impulses of the masses.”

In Britain trade union membership had risen from 6,053,000 in 1938 to 7,803,000 in 1945. The growth wasn’t just numerical but was accompanied by increased militancy. This was reflected in the 1944 TUC congress adopting a radical programme for post-war reconstruction, which was subsequently echoed in the Labour party’s 1945 election programme which stated that the Party’s main aim was “the establishment of the Socialist Commonwealth”.

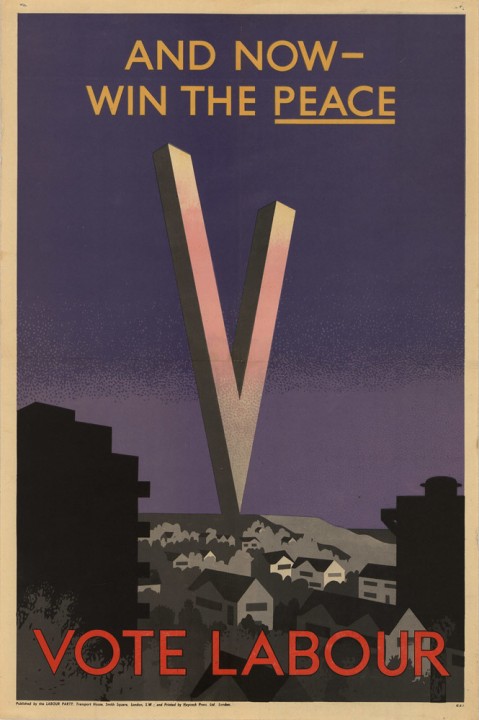

With a radical socialist programme to break with the poverty, misery, and unemployment of the war years, the Labour Party swept to power in 1945. The newly organised and radicalised working class in Britain hurled Labour into power with an unprecedented 393 seats in the House of Commons, and with big expectations about the fundamental changes Labour was going to bring.

Unfortunately, the leaders of this Labour government confined themselves to modifying capitalism rather than uprooting and replacing it with a socialist society. They squandered the mood and energy of the masses who would have supported a Labour government striking fundamental blows against the capitalist system, which has caused so much death and destruction. It was this failure which laid the basis for the Conservative election victory in 1951. But although the Labour leaders proved unwilling to break the rules of the capitalist system, the attitude of the ‘workers in uniform’ after the end of the war offers a stark contrast and an indication of the mood of the British working class at this time.

The working-class men serving in the British army in South-East Asia had not been allowed to return home after the end of the war, as the British imperialists tried to retain some of the Empire’s influence and assets in the region. Infuriated by this, the soldiers felt that they were missing out on the enthusiasm for the new radical Labour government of 1945, and all that it promised in new jobs and higher education, simply to continue fighting for something they didn’t believe in.

The result was that, in Malaya, British troops were openly attending communist rallies. In January 1946, the RAF in Karachi went on strike. This was followed by 4,000 troops, including officers, striking at the Seletar air base in Singapore. And another 5,000 walking out at Cawnpore air base in India.

The RAF strike soon extended beyond South-East Asia through the Middle East to Egypt and North Africa, as far West as Gibraltar. At its height 50,000 RAF servicemen were on strike.

Faced with repression by the military authorities, the strike spread to the navy when the HMS Northway in Singapore harbour refused orders and the Royal Indian Navy in Mumbai mutinied. By May 1946 it had spread to the army when the Parachute Regiment in Malaya rebelled against orders. At first, 240 soldiers were sentenced to prison, but such was the outcry back in Britain that the convictions were quashed.

The mood of soldiers on the front line was one of such anger and frustration that they were seeing none of the benefits for which they supposedly fought, that they were willing to break military law through mutinies. So powerful was this movement that the British military authorities could not punish the soldiers, but instead simply acceded to their demands as quickly as possible through rapid demobilisation. Not only was this a victory for these working-class men who participated in the mutinies, but it also landed a huge blow against the power of British imperialism which had been a scourge on the masses of South-East Asia for decades.

It is impossible for us to predict what society will look like in detail on the other side of this coronavirus crisis. But what seems inevitable is radicalisation akin to that of a war situation, which will produce a powerful move to the Left for millions of working class people.

The questioning of the entire structure of society, and the burning desire for fundamental change, is already setting in for many people. The conditions in which radical, socialist ideas can get an echo are becoming more favourable by the day. As it did in 1945, this mood is highly likely to find an echo in some form inside the Labour party, where many members and voters have learned a lot about the fight for socialist policies in recent years through Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the party.

And we can anticipate the mood being particularly radical and sharp among those who have been on the front lines, just like the British troops in South East Asia in 1946. Those NHS staff, and other key workers, who have been forced to risk their lives and the lives of people they love to keep working throughout this crisis will rightly be the first to demand improvements to the standard of living and working conditions for low-paid working class people.

They will demand proper investment in the NHS, a rolling back of the austerity and privatisation imposed on social care and other public services over the last 10 years, and support for their friends and colleagues who have lost their jobs as a result of this crisis. When the capitalist class and their Tory representatives point to massive piles of debt and a struggling economy to claim that this isn’t possible, the mood of radicalism and the willingness to fight to overthrow this entire rotten, inefficient and corrupt system is likely to explode.

The role of leadership

Despite all the industrial struggle during the war, the leaders of the Labour Party maintained a wartime coalition with the Tories. It was a Labour minister who prosecuted striking workers! Meanwhile the trade union leaders were determined to maintain an industrial truce to keep production running to help the war effort, leading them to organise against striking workers.

Despite all the industrial struggle during the war, the leaders of the Labour Party maintained a wartime coalition with the Tories. It was a Labour minister who prosecuted striking workers! Meanwhile the trade union leaders were determined to maintain an industrial truce to keep production running to help the war effort, leading them to organise against striking workers.

After the war, despite the yearning for a fundamental change in society, the 1945 Labour government did not base itself on the radicalised masses to break with capitalism. Instead it ended up handing power back to the Tories in 1951.

The extent to which the leaders of the labour movement were out of touch with the radicalised working class during and after the war should be a lesson for us today. Especially as Sir Keir Starmer starts eyeing up a seat in a national government coalition with the Tories and talking about ‘behaving responsibly’ by only criticising the government’s shambolic handling of the coronavirus crisis ‘when the time is right’. Such talk will not go down well as the crisis develops.

The impact of this coronavirus crisis will lead many more people than in the past to draw radical and even revolutionary conclusions. It will only be with a leadership that is willing to break with capitalism and embark upon the construction of a new socialist society that we can realise the enormous potential to dramatically improve the lives of millions of working-class people. Educating ourselves in revolutionary political theory, agitating for socialist ideas, and organising to establish this leadership, in the Labour party and the trade unions, are the tasks before every socialist activist today.