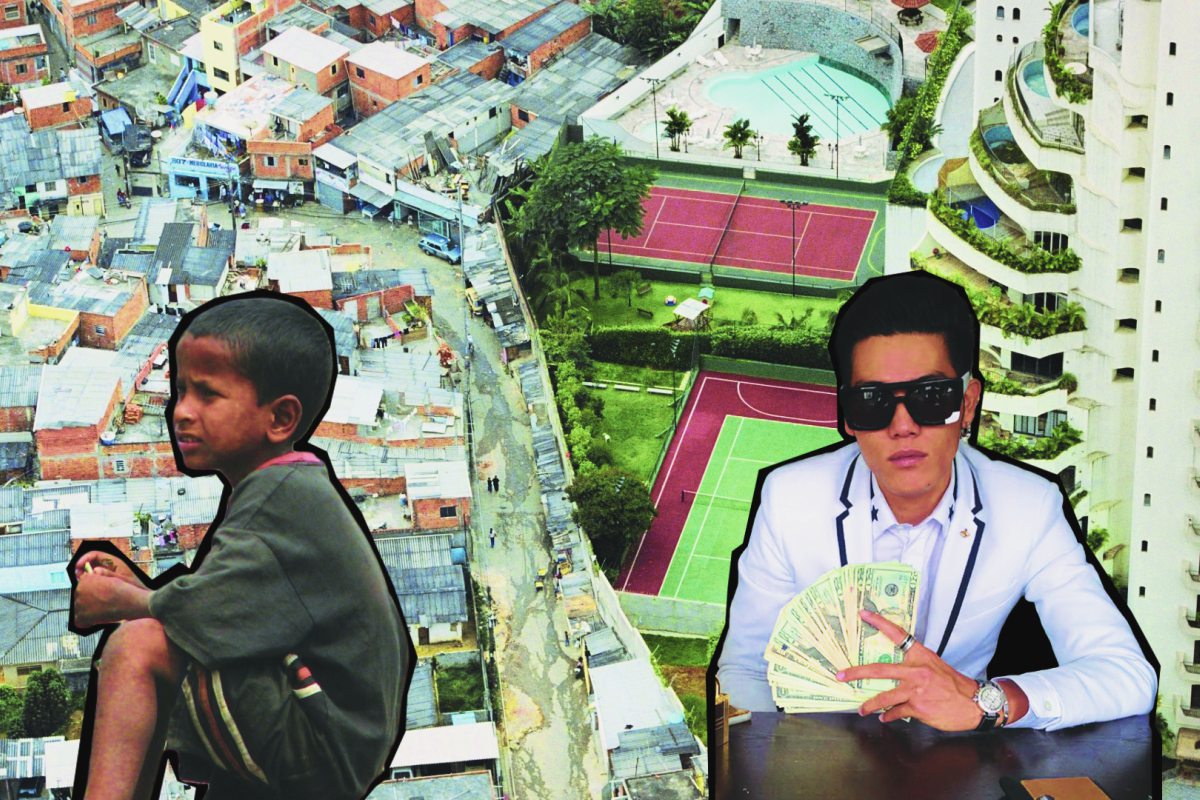

The ‘progressive’ apologists of capitalism claim that their system is helping the global poor. But in fact it is condemning billions to a life with no future.

In the years following the global financial crisis of 2008, the world has seen the most widespread questioning and rejection of the capitalist system since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The intractable crisis of the world economy is making itself felt in all spheres of life, causing immense instability in politics and world relations.

Across Europe, political parties that had shaped the postwar era have been reduced to mere footnotes as insurgent ‘populists’ rise to prominence, while in the UK the Brexit vote has brought the centuries-old Tory Party to the brink of self-destruction. In Latin America, Africa and the Middle East, enormous protest movements have brought down governments, and in the USA, the richest nation on Earth, the election campaigns of Sanders and Trump have rocked the formerly unshakeable two-party system to its foundations and, in the words of The Financial Times, “dispatched the electoral equivalent of a suicide bomber to Washington”.

Such a deep social crisis has inevitably found its reflection in mass consciousness, particularly amongst young people, who in many parts of the world are facing higher unemployment, lower incomes and more precarious living and working conditions than their parents.

In a survey conducted by the ‘Victims of Communism Foundation’, 44 percent of US millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) said they would prefer to live in a socialist society, as opposed to 42 percent who preferred a capitalist one. 7 percent (a significant number) even said they’d prefer to live under communism, prompting a wave of consternation in the press.

This shift is by no means restricted to the USA. In Europe, an EU-sponsored survey of 18-25-year-olds found that the majority of those polled would “actively participate in a large-scale uprising against the generation in power if it happened in the next days or months”, with 89 percent agreeing with the statement, “banks and money rule the world”. One might say a spectre is haunting Europe…

But this is by no means a one-sided process. As more and more people turn away in anger from the status quo, and commentators lament the “death of Liberalism”, an unholy alliance of billionaire philanthropists, politicians and celebrity intellectuals have risen to a panicked defence of capitalism under a somewhat unexpected banner: poverty reduction.

The ‘silent miracle’

In the UK, Theresa May has been compelled to mount a defence of capitalism, lauding the free market as “the greatest agent of collective progress in our history” along with claims that when countries adopt free-market policies, “absolute poverty shrinks and disposable income grows”.

In the UK, Theresa May has been compelled to mount a defence of capitalism, lauding the free market as “the greatest agent of collective progress in our history” along with claims that when countries adopt free-market policies, “absolute poverty shrinks and disposable income grows”.

In 2016, former President Barack Obama responded to the election of Donald Trump with an article claiming, “now is the best time to be alive” – which it probably is if you’re Barack Obama.

Bookshelves bulge with bestsellers such as Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now and Hans Rowling’s Factfulness (released posthumously this year), heralding the “silent miracle of human progress”. Beneficent billionaires like Bill Gates assure us, “Trust me, the world is really getting better”, whilst handing out free copies of Rosling’s book.

Major news outlets like The Economist report “the number of people in extreme poverty fell by 137,000 since yesterday” whilst lamenting the lack of media coverage for this incredible achievement. Slick websites such as the “World Poverty Clock” pop with flashy infographics demonstrating the decline of poverty rates around the world.

Liberals and figures from the alt-right such as Jordan Peterson are united in chorus: “Between 2000 and 2012, the level of absolute poverty in the world was cut by 50 percent. That was the fastest rate of improvement by a large margin in human history.”

An entire industry has arisen out of simply telling people how good the status quo is – another marvel of the free market.

So if things are going so well, why are most people convinced of the opposite?

According to Pinker and Rosling, the fault lies in the “ignorance” of the masses and their instinctive tendency to assume the worst, even when their superiors tell them otherwise. Rosling notes that, when asked how many people around the world are living in poverty, people “systematically get the answers wrong”.

The answer? A healthy dose of “factfulness: the stress-reducing habit of only carrying opinions for which you have strong supporting facts”.

The logic of this argument is powerful in its simplicity: If the ‘facts’ state that on almost every measure the state of the world is improving, then surely for all its imperfections the system works. And if the system is working for most people then there is no reason for people to turn to ‘populists’ of the right and left, except for a combination of ignorance and prejudice. Liberalism is back with a vengeance.

But when it comes to world poverty, fact and fiction are regularly blended together.

The politics of poverty

One interesting fact that should be mentioned is that the poverty statistics reported by Pinker, Rosling and Peterson have all been drawn from exactly the same source: the World Bank.

One interesting fact that should be mentioned is that the poverty statistics reported by Pinker, Rosling and Peterson have all been drawn from exactly the same source: the World Bank.

Since 1981 the World Bank has been compiling data from all over the “developing” world in order to report the number of people living in “extreme” or “absolute” poverty, classified as below the International Poverty Line (IPL). Today the IPL is $1.90 a day in terms of 2011 Purchasing Power Parity (the equivalent quantity of currency needed to buy a given “basket” of goods).

At first sight it may seem surprising that the monitoring of global poverty should be almost exclusively carried out by the world’s most prominent representative of finance capital. But skeptics should take heed of the World Bank Group’s mission statement, carved in stone outside of its Washington headquarters: “Our Dream is a World Free of Poverty”.

For decades the World Bank has been pursuing its dream of a world free of poverty by issuing loans to states in the developing world and selling on the debt to Wall Street investors with attractive returns of up to 15 percent.

In order to gain access to these loans, debtor countries must agree to IMF “structural adjustment”. In the event that they are unable to pay back the money received, they will be forced to sell off public assets and cut public spending, pensions etc.

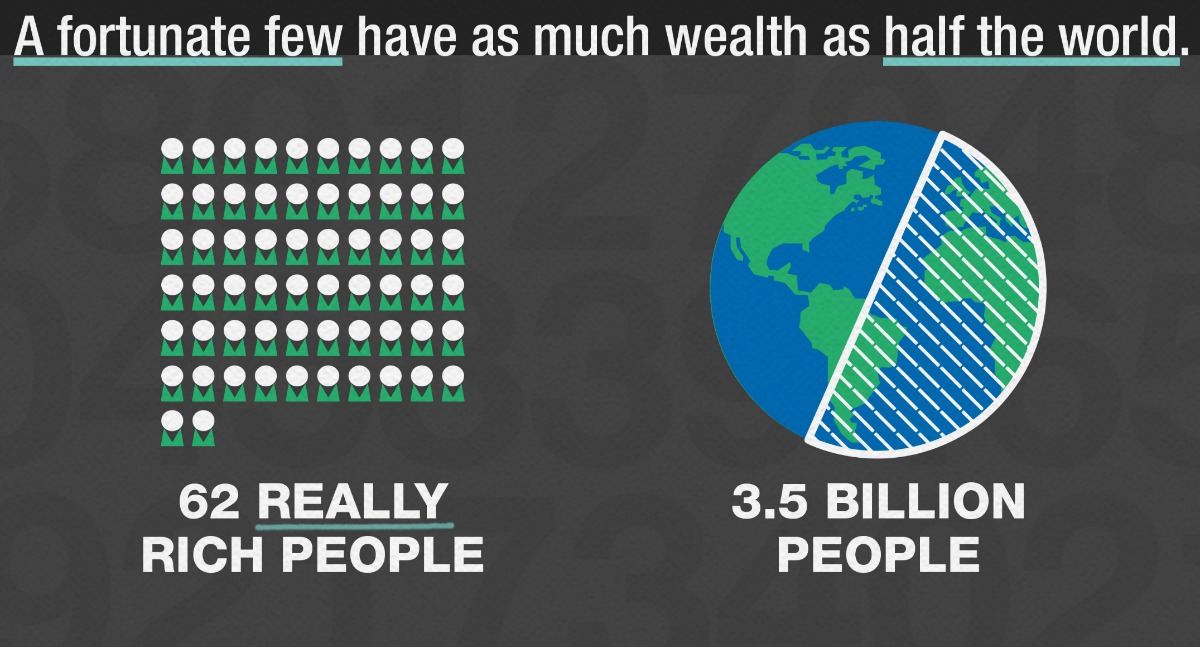

Such a policy, identical to the one followed by the European Central Bank in relation to Greece, succeeded in reducing GDP per capita growth in the developing world from 3.2 percent in the 1960s and 1970s to 0.7 percent in the 1980s and 1990s. By 2015 it had brought half of the world’s wealth into the hands of 1 percent of the world’s population.

But in the same year, the World Bank reported that the proportion of people in the world living on the equivalent of less than $1.90/day fell from roughly 4 in 10 in 1990 to less than 1 in 10, with the most rapid progress being made after the year 2000, including during the world recession that followed the 2008 financial crash.

Such gravity-defying statistics have obvious political value. If, despite the concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer hands, the world has reduced poverty at the fastest rate ever recorded, then perhaps Thatcher and Reagan were right and capitalism is indeed the “rising tide that lifts all ships”.

If this all seems too good to be true, that’s because it is. Aside from the obvious conflict of interest involved in an institution reporting on the results of its own policies, the data produced, and the assumptions that flow from it, have a much looser relation to fact than “impatient optimists” like Bill Gates would have us believe.

The myth of absolute poverty

When politicians and publications speak about the reduction of poverty, they almost always mean “absolute poverty” (also referred to as “extreme poverty”). This is defined by Our World in Data as a minimum “fixed standard of living” that is “not just held constant over time, but also across countries”, i.e. the bare minimum required for human survival, set at the IPL of $1.90/day.

When politicians and publications speak about the reduction of poverty, they almost always mean “absolute poverty” (also referred to as “extreme poverty”). This is defined by Our World in Data as a minimum “fixed standard of living” that is “not just held constant over time, but also across countries”, i.e. the bare minimum required for human survival, set at the IPL of $1.90/day.

The problem is, as superficially scientific as it may appear, it turns out the idea of absolute poverty, fixed and constant for all places and times, is absolute nonsense.

Pinker, in his defence of capitalism and Enlightenment values, refers to the IPL as “the minimum amount of income necessary to feed your family”. Unfortunately, almost every word of this is false. Firstly, because the IPL is actually calculated with regard to consumption, not income. But more importantly, it is so low that in most countries it would not be sufficient to feed anyone’s family.

In 2005, the US government reported in its “Thrifty Food Plan” that the average person needed a minimum of $4.58 a day just to meet minimum nutritional requirements – more than double the “absolute minimum” selected for the IPL. In fact, someone living on the streets of London would succeed in lifting him/herself out of extreme poverty each day simply by consuming a single sandwich from any supermarket.

Even in the developing world, the IPL fails to provide an adequate baseline. The $1.90/day figure currently used by the World Bank is based on the average taken from the poverty lines of the 15 poorest countries on Earth, including the Gambia and Sierra Leone. This means that the minimum level of consumption for a largely rural and often subsistence farming population, calculated on the basis of irregular and patchy surveys, becomes the baseline for every country included in the World Bank’s definition of “developing countries”, including China, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Argentina.

Unsurprisingly, a flawed method produces absurd results. Pakistan is a case in point. According to the World Bank, Pakistan’s efforts to reduce poverty (aided by over $5bn in World Bank loans) have been very successful, with its poverty rate falling from 15.9 percent of the population to 6.1 percent between 1996 and 2013. The World Poverty Clock, extrapolating from the World Bank’s data, has even been so bold as to declare the level of extreme poverty in Pakistan “below 3 percent”.

But according to Pakistan’s own National Nutrition Survey of 2011, a third of all Pakistani children are underweight, nearly 44 percent have stunted growth and half of them are anaemic. Most discouraging of all, the level of child and maternity hunger in Pakistan has hardly changed over the last two decades according to a study published in The Lancet in 2013. Nor has the situation much improved since then. According to the Global Hunger Index 2016, 22 percent of the population is “undernourished” and 8.1 percent of children die before the age of five due to malnourishment.

India, often held up as the poster child for poverty reduction, offers another example. In 2015, a spokesman for the Indian government made a speech acknowledging the plight of 300m people who are both unemployed and landless, often from tribal or lower-caste backgrounds. However, the World Poverty Clock estimates that in January 2016, less than half of that figure, roughly 145m people, were considered to be living in “extreme poverty”.

Outside of Asia the picture is equally confusing. In 2010, the Mexican government reported a poverty rate of 46 percent. The World Bank set it at 5 percent.

Worldwide, the UN has reported that a total of 815m people suffered from chronic undernourishment (lasting over a year) in 2016, and the figure is rising. But in 2013, the World Bank reported that only 767m were classified as living in absolute poverty and it estimates that in 2016 the figure was even lower. It is a miraculous system indeed which can lift people out of poverty without putting any more food in their mouths.

As Marx wrote in 1859, “There must be something rotten in the very core of a social system which increases its wealth without diminishing its misery.”

The fact is that the whole notion of a special category of “extreme” or “absolute” poverty simply does not work. What it does achieve however is the production of cheery statistics to back up the policies proposed by the World Bank and its main shareholder, the USA.

But what is worse is that even using this measure, designed to produce as favourable a result as possible, the World Bank has been forced to doctor its own figures and shift the goalposts on several occasions.

Damned lies and statistics

In his book, The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, the LSE academic, Jason Hickel, gives a concise history of the statistical jugglery carried out by the World Bank since it set itself the target of first halving, then eliminating extreme poverty – what he calls “The Great Poverty Disappearing Act”.

In 2000, the world’s leaders met in New York to sign the UN’s Millennium Declaration, which set a target of reducing the proportion of people living below the poverty line (then set at $1.02 a day) by half. But not long after, the World Bank announced in its 2000 annual report that the number of people living on less than $1.02 a day was actually increasing, and had risen from “1.2bn in 1987 to 1.5bn” in 2000, and was predicted to reach 1.9bn by 2015. And yet, in 2001, the World Bank’s president, James Wolfensohn, announced that “since 1980, the total number of people living in poverty worldwide has fallen by an estimated 200m”.

How did they achieve such a rapid turnaround? Simple: they changed the IPL. The World Bank periodically updates the IPL to factor for inflation. In theory, it should improve data accuracy, but in practice, it has regularly been used to massage the statistics to show the best possible progress towards the UN’s Millennium Development Goals. For example, the 2001 poverty line of $1.08 was, in fact, lower in real terms than the previous IPL. As Hickel explains, “the poverty headcount changed literally overnight, even though nothing had changed in the real world”.

This was not the only time the World Bank has shifted its own goalposts. The IPL was revised again in 2005 from $1.08 to $1.25. This time the shift actually increased the absolute number of people living below the IPL but, crucially, greatly improved the trend of development, i.e. the proportion of people living under $1.25 had fallen much more rapidly between 1990 and 2005 than the proportion living under $1.08.

This matters because the goal set for the World Bank had been to reduce the proportion of the world’s population living under the IPL by half, not to reduce the absolute number. And sure enough in 2013, two years before its 2015 deadline, the World Bank proudly announced that it had already succeeded in reaching its goal.

Perhaps inspired by Stalin’s famous slogan, “Achieve the five-year plan in four years!”, the global Establishment and media fell over themselves to proclaim the success of the 15-year plan in 13 years.

The most recent act of statistical manipulation by the World Bank occurred in 2015, with the setting of its current IPL of $1.90/day, which is actually lower than the previous $1.25 in real terms. Most likely, as the UN’s latest Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating extreme poverty altogether by 2030 draws near, we will see more silent miracles performed with the World Bank’s figures.

Uneven development

The public relations campaign over world poverty has been relentlessly exaggerated, often with little reference to actual fact. But even though the number of people claimed to have ‘escaped’ poverty is false, how can the overall trend be explained?

The public relations campaign over world poverty has been relentlessly exaggerated, often with little reference to actual fact. But even though the number of people claimed to have ‘escaped’ poverty is false, how can the overall trend be explained?

The IPL may be absurdly low, and the surveys which contribute to its calculation are often patchy and unreliable, but there has still been a marked shift of population above the IPL, although often not out of poverty in any real sense.

The driving force behind this shift has been the wave of urbanisation which has swept the world in the last 30 years. Millions of people are moving, voluntarily or otherwise, from their ancestral villages into the cities, where many are joining the world’s growing working class. This has had a huge impact on poverty statistics: the World Bank itself notes that in 2013, 76% of the “world’s poor” (defined as living under the IPL) lived in rural areas.

The reason for this is not because urban life is automatically better than life in a rural village, as anyone who has seen a slum can attest, but that life in the cities usually entails a greater access to and dependence on the consumption of commodities – the primary means of calculating someone’s livings standards for the IPL.

This process has also been extremely uneven. China has been the biggest contributor by far: in 1990, 74 percent of the Chinese population lived in the countryside, but in 2012 it was announced that for the first time in China’s history more people lived in urban centres than the countryside, which reflected a shift of roughly 200m people, more than the entire population of Nigeria. By 2017 the urban population had increased by another 300m.

Of these 500m new city dwellers, a layer has certainly seen a marked improvement in living standards associated with the country’s huge state-led investment and export-driven growth of the last 30 years. But this success story is only a part of the picture, and a smaller part at that. A large part of the new urban population in China has been pulled into the 21st century equivalent of the “satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution, working long hours in unbearable conditions for low wages.

The infamous Foxconn assembly plant in Shenzhen, which in 2015 employed an estimated 500,000 workers, provides a good example. As reported in The Guardian, following an “epidemic” of worker suicides at the plant, “survivors told of immense stress, long workdays and harsh managers who were prone to humiliate workers for mistakes, of unfair fines and unkept promises of benefits”. Foxconn CEO, Terry Gou, “had large nets installed outside many of the buildings to catch falling bodies”. Even today, workers complain of being forced to work 12-hour shifts.

But at an average wage of roughly $390/month, the Foxconn worker is considered comfortably above the ranks of the “extreme poor” and can even count him/herself as part of the “global middle class”. Others aren’t so ‘lucky’. Shenzhen has the highest monthly minimum wage in China, whereas workers in Heilongjiang, for example, can expect little over half as much. Further, an estimated 200m people live in slums on the edge of China’s growing megacities, often working in precarious employment with little reliable income.

India provides an altogether different picture of urbanisation in the developing world. An estimated “30 Indians move from a rural to an urban area every minute”, according to a report quoted in The Financial Times, but the low level of investment in industry and infrastructure has left many new town dwellers trapped in the so-called “informal sector” as stall owners, rickshaw drivers etc., scraping a precarious existence on the streets of India’s immense but crumbling cities.

An article in the India Times laments India’s development into “a country of urban poor” where “basic necessities such as water, electricity, sewerage and sanitation remain a major problem”. A census of 2011 reported that 17.4 percent of urban households, roughly 65m people, lived in areas “unsuited for human habitation”, and as the gulf between India’s rich and poor widens, the slums have continued to grow, with more than a million people living in Dharavi, a single slum in Mumbai.

With unemployment on the rise and investment in real production actually falling in India, it is difficult to understand why so many people are continuing to “lift themselves” out of the poverty of the village and into the poverty of the city.

The answer to this riddle has little to do with raising living standards and more to do with the old way of life becoming impossible. Today in India, thousands of peasant families are being crushed by debt. Many are forced to sell their land and are left homeless. Those who manage to migrate to the city become part of the “urban poor” and miraculously disappear from statistics on global poverty. Those who cannot have increasingly been driven into suicide, ending their poverty by less miraculous means.

The growing crisis for the urban poor is by no means limited to India. Pakistan boasts the world’s largest slum, Orangi Town in Karachi, with over 2m residents (larger than the total population of the North of Ireland). In Lagos, Africa’s largest city, 65 percent of the population lives in slums, while roughly 300,000 are homeless – and yet the majority of the world’s urban poor are excluded from the World Bank’s extreme poverty statistics. Worldwide, the UN estimates that around a billion people in total live in slums, but using the yardstick of the IPL, we are told urban poverty stands at less than 200m.

A bitter future

Piercing through the sandstorm of misinformation thrown up in the media, it becomes apparent that world poverty is a growing, not a diminishing problem.

Piercing through the sandstorm of misinformation thrown up in the media, it becomes apparent that world poverty is a growing, not a diminishing problem.

Many economists have argued that a poverty line of $5 a day would be much closer to the real level of people’s basic needs. Using this “ethical poverty line”, Hickel estimates that the global poverty headcount would stand at “about 4.3bn people… more than 60 percent of the world’s population”. Moreover, this figure would represent an increase of over 1bn people compared to 1990. On this basis the truth is clear to see: the world has never been richer, and yet there are more people living in poverty today than at any other time in human history.

Worse still, the World Bank itself has warned that even on its own flawed measure of global poverty, the great poverty reduction miracle may have stalled, and it is looking increasingly doubtful that the goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030 will be achieved on time, if at all. In Africa and Latin America, the proportion of people living under the IPL is actually rising.

This fact should surprise no one considering the vast transfer of wealth from these regions to the ‘developed’ world. A study published by Global Financial Integrity and the Norwegian School of Economics reported that in 2012, developing countries received a total income of just over $2tn including aid, investment, remittances etc. But in the same year, a total of $5tn flowed out of them and into the developed countries. Hickel explains that this net outflow of $3tn is 24-times larger than all the aid budgets in the world put together, so “for every dollar of aid that developing countries receive, they lose $24 in net outflows”. For every school built, well dug or food package sent therefore, the bosses and banks of the West receive 24-times that amount back through debt and interest payments, resource extraction, and a large helping of outright fraud.

The prophets of ‘facts-based’ thought don’t quote this figure when they are telling Western workers how good things are. This might be because it fundamentally contradicts the story we have been told about world poverty for decades, and offers little evidence for their Panglossian belief that if we leave the bankers and billionaires to their good work, all will be for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

And things are likely to get worse, not better, over the coming years. The perspective for developing economies in the short-to-medium term is not nearly as rosy as we are sometimes led to believe. In April this year, The Financial Times published an alarming article reporting that 40 percent of Sub-Saharan African nations are “slipping into a new debt crisis”, only 13 years after billions of dollars of African debt was written off in 2005. With interest payments doubling over the last decade to more than 20 percent of tax revenues, countries like Ghana are warning of 20 years or more of crisis – a lost generation.

The IMF has offered up its usual medicine, urging debt-stricken countries to “increase the efficiency of public expenditure, hand over public investment to the private sector, and fully implement fiscal consolidation plans, including seeking new revenues from consumer taxes”. The effect of this on African workers’ living standards will be predictably disastrous, and no amount of statistical trickery will be able to hide it.

India is also at risk. In order to sustain the current flow of people from the villages into its growing cities, India must grow its economy by about 8-10 percent a year – a figure agreed by many economists. It last reached 8 percent in July 2016. In the meantime, the state has been wracking up an increasingly unsustainable fiscal deficit, while the level of “bad loans” has risen to 11.6 percent of all loans. To put that in context, the extent of bad loans in the Italian economy, which has been threatening the stability of the entire Eurozone, currently stands at 11.1 percent.

If rising interest rates in the USA should pull investment away from so-called ‘developing markets’ such as India, which historically they have done, at the same time that the price of basic commodities such as oil are increasing internationally, the recent debt-driven growth of the Indian economy could go into reverse, provoking an explosion of unemployment and even an exodus from the cities as workers return to the villages. Such a scenario would effectively be a repetition of the East Asian crisis that struck in 1997, only this time in the world’s sixth-largest economy, set to be the world’s most populous country by 2024.

Factoring in the impact of climate change, which is already hitting developing countries hardest of all in terms of extreme weather events, water shortages and crop failures, a serious perspective for the world’s poor offers little hope for miracles in the near future. In fact, if the capitalist plunder of the world and its people is allowed to continue, the outcome will be a human catastrophe of unprecedented and unimaginable scale.

Poverty creation

It is often said that the world’s capitalists are ‘wealth creators’. But it must be asked, where does their wealth come from? According to capitalists themselves and their various representatives, the answer is simple: ‘enterprise’, ‘risk-taking’ or ‘innovation’ on the part of the capitalist class, which benefits all, including the poor, by giving them much-needed employment.

It is often said that the world’s capitalists are ‘wealth creators’. But it must be asked, where does their wealth come from? According to capitalists themselves and their various representatives, the answer is simple: ‘enterprise’, ‘risk-taking’ or ‘innovation’ on the part of the capitalist class, which benefits all, including the poor, by giving them much-needed employment.

In fact, it is precisely the opposite. Throughout the history of capitalism, the source of the capitalists’ wealth has been the poverty of the masses.

This fact did not go unnoticed by the bourgeois of the past. As the philosopher, Bernard de Mandeville, wrote as early as 1728, “it is manifest, that, in a free nation, where slaves are not allowed of, the surest wealth consists in a multitude of laborious poor; for besides that they are the never failing nursery of fleets and armies, without them there could be no enjoyment, and no product of any country could be valuable”.

The profits that form Bill Gates’ billions ultimately stem from the unpaid labour of the working class: the difference between the value of the product of the workers’ labour (be it in goods or services) and the wage they receive. The bigger this difference, the greater the profit, creating an immense pressure to lengthen hours and ‘reduce labour costs’, i.e. force down wages and conditions.

This is not a one-sided process of course, and in the past, the workers have won even considerable gains in the form of higher wages, shorter hours and better working and living conditions. But wherever the workers have succeeded in winning such concessions, the bosses have fought back with all the means at their disposal. In the west in particular, de-industrialisation, austerity and union-busting have all been used as part of a race to the bottom, which forces workers to compete with each other for the privilege of making someone else rich.

But capitalism is also a global system; it therefore forces workers to compete on a world scale, driving the formation of a larger and larger class of poor and propertyless workers, from which huge corporations can pick and choose. In this way, the ‘wealth creators’ can pay one set of workers poverty wages in one country whilst forcing down the wages of another to an acceptable level, all the while congratulating themselves on their tremendous poverty reduction!

The overall result is not the lifting of humanity from the depths of poverty but rather the forcible maintenance of the overwhelming majority of the world’s population in a state of slavery – too poor to escape from exploitation but not poor enough to starve. But for millions today, the capitalist system cannot even “assure an existence to its slave within his slavery”, as Marx wrote in the Communist Manifesto. The UN estimates that 20m face starvation in South Sudan, Nigeria, Somalia and Yemen as part of the worst famine since the Second World War. Meanwhile, all over the world suicide rates are on the rise: an eloquent appraisal of the progress made by capitalism over the last 30 years.

Wherever it has spread (and today that is everywhere on Earth), capitalism has brought with it the rapid accumulation of both wealth and misery. This system of poverty creation, and the tiny class of exploiters who benefit most from it, are as capable of eliminating poverty as a tiger is of removing its own claws.

The case for optimism

And yet, there is both need and cause for optimism today: not the false promises of “impatient optimism” offered by the likes of Bill Gates, but a revolutionary optimism, founded on the belief that the oppressed and exploited masses of the Earth can, and must, seize control of the incredible wealth they produce and use it to build a future fit for humanity.

And yet, there is both need and cause for optimism today: not the false promises of “impatient optimism” offered by the likes of Bill Gates, but a revolutionary optimism, founded on the belief that the oppressed and exploited masses of the Earth can, and must, seize control of the incredible wealth they produce and use it to build a future fit for humanity.

Today, we produce enough food for 10bn people, while millions starve. Companies and tax havens sit on a cash pile of trillions of uninvested dollars that could be used to revolutionise production, tackle climate change, and provide decent and sustainable living conditions for all. None of this is necessary or inevitable; it is the product of a system that draws the profit of the few from the poverty of the many. But this can be stopped.

All over the world we see the stirrings of millions against their poverty and exploitation. This is what the billionaire philanthropists fear most. To stand with the masses in struggle and to fight for a new socialist world, a world genuinely free of poverty in all its forms, is the only way to end the barbarism wrought by the capitalist system. We have every reason to be optimistic in this fight: we have a world to win.