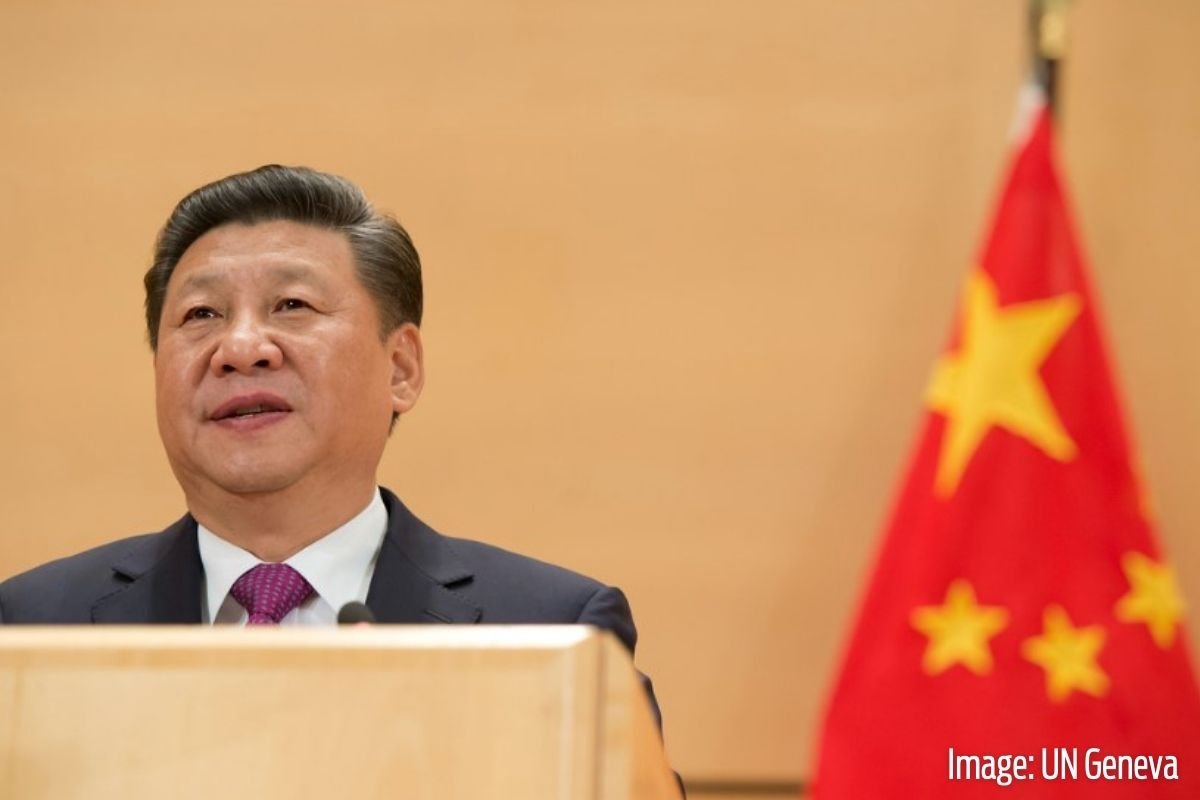

At the recent 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, President Xi Jinping took the opportunity to let the world know that China is a “mighty force” soon to reclaim its rightful position on the world stage. Behind all the bluster, however, one could detect an unease at the prospect of growing internal instability within China, which flows from the impending crisis of capitalism.

At the recent 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held on 18-24 October in Beijing, Xi Jinping took the opportunity to let the world know that China is a “mighty force” soon to reclaim its rightful position as the “Middle Kingdom”, i.e. the centre of humanity. Behind all the bluster, however, one could detect unease at the prospect of growing internal instability that flows from the impending crisis of capitalism.

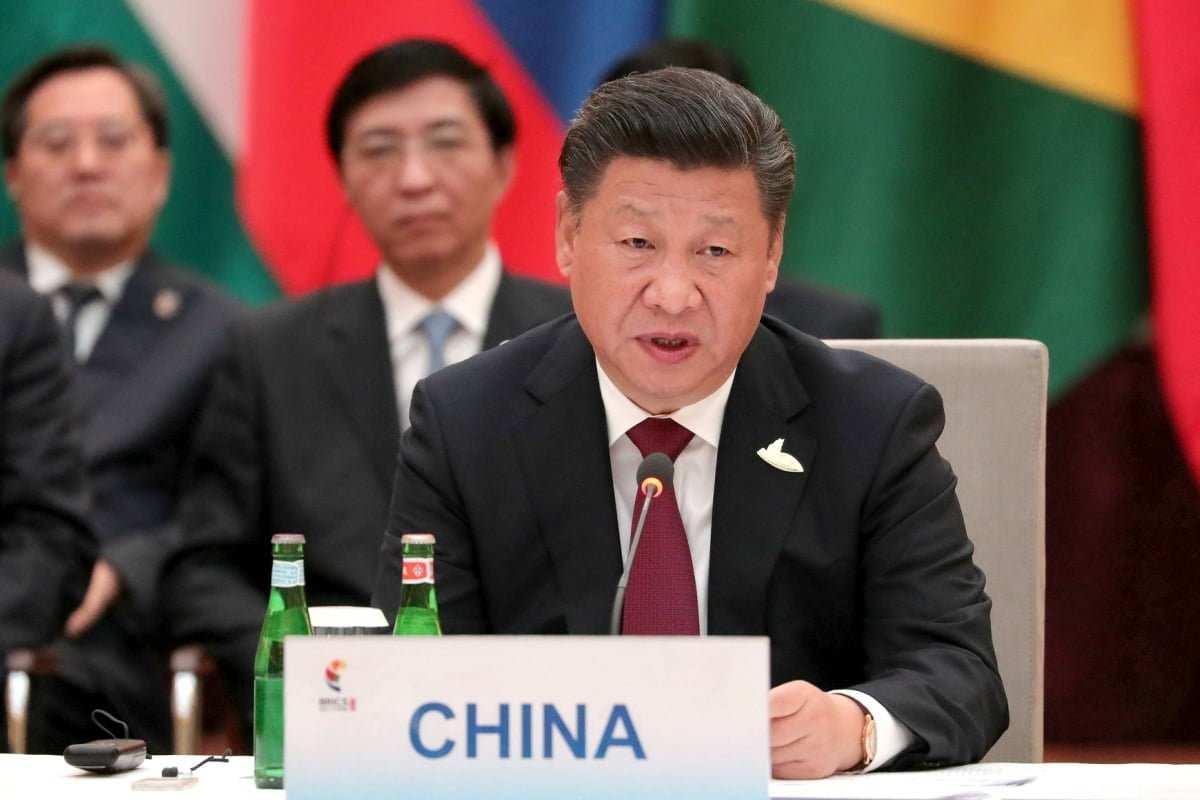

The Congress was a rare occasion for the world’s media and politicians to get a glimpse of the Chinese state’s perspectives and priorities. The two main features of the Congress were Xi Jinping’s opening speech and the announcement of the new Politburo Standing Committee, the leading body in the Chinese state.

Both of these have been perceived in the Western media exclusively through the prism of their liberal preoccupation with Xi’s increasing concentration of power, which they also fear is leading China away from capitalism and back towards Maoism. But for those of us not blinded by liberal prejudices, it is clear that the centralisation of power serves the very opposite purpose: the further strengthening of capitalism throughout China.

Since taking office in 2012, Xi Jinping’s administration has been characterized by his marked elevation as preeminent leader of China; his high-profile anti-corruption campaign against powerful Party bosses; his gratuitous quotation of Mao; and his halting of the privatization of state owned companies. Many of these traits have led some in the West to believe that Xi has a program of returning to the Mao era of a nationalized planned economy under a Stalinist party dictatorship.

In its balancing act of transforming China into a capitalist economy whilst maintaining its old state power, the Party has occasionally had to strike against individual capitalists, corporations, and rival bureaucrats that are acting out of line and threatening the system’s stability. Such is the case of Guo Wengui, a maverick real estate tycoon who escaped from corruption investigations in China and regularly recounts and exposes corrupt Chinese officials on Youtube, particularly Wang Qishan, from his penthouse apartment in the US.

Xi’s anti-corruption crusade may be intended to weed out ‘loose cannons’ or other threats to stability. However, in and of itself it too contains the risk of adding to the growing instability. For this reason it represents a dramatic departure from the more “behind closed doors” policy taken by the Party bureaucracy in the aftermath of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. However, beneath all the high-sounding rhetoric, it is clear from the perspectives outlined at the Party Congress by Xi Jinping himself, that increasing liberalization and deepening of the market is at the top of its agenda.

The Standing Committee

With bated breath the world’s capitalist media and politicians awaited the appointment of the new Politburo Standing Committee. This is a rare chance for the rest of the world to peak ‘behind the curtain’; its composition would reveal just how strong Xi is and what line he is likely to take.

This year, as the western liberals fearfully anticipated, the new Standing Committee is a break from Party tradition in several ways. Rather than being a result of factional horse-trading and collective rule, the new roster is clearly dominated by those who are subordinate to Xi. It has been noted that none of the new Standing Committee members can be seen as a potential future successor to Xi, yet another break from the unspoken Party tradition that a future leader should be a part of the SC before taking over. This thus lays the basis for Xi to pursue an unprecedented third term in power. This break with tradition may also permanently alter the way the SC is formed, as Xi’s personal influence in deciding its composition has undermined the traditional use of straw polling of Politburo members to decide.

In his first term Xi had to share a SC slate with senior leaders of different factions such as Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengsheng and Zhang Gaoli, which required him to lean heavily on Wang Qishan for his anti-corruption campaign against rival bureaucrats. The new Standing Committee slate now sees 5 new members (out of 6 who are not Xi Jinping) who were promoted by Xi or in complete agreement with his views.

Li Zhanshu, who has been close to Xi since the two were both county officials in Hebei Province in the 1980s, is viewed as one of Xi’s strongest lieutenants in the Party Secretariat in the recent period. Wang Huning had been the Secretary General for the Office of Deepening Reforms, one of the new central organs created by Xi to push his economic reforms. He has often been viewed as the chief pro-market ‘theoretician’ in the recent period. Zhao Leji, who will succeed the outgoing Wang Qishan as the new anti-corruption tsar, impressed Xi with his strong support for Wang’s anti-corruption campaign as the head of the Party’s Organization Department, especially in his prominent role in tackling the rampant failure to pay dues by Party members. He will be entrusted with the founding of the National Control Committee as the new organ to combat corruption, as laid out by Xi and Wang Qishan. Wang Yang is a vocal ‘reformer’ who enforced the marketization of the key province of Guandgong and has worked closely with Li Keqiang (the current Prime Minister). The odd man out is clearly Han Zheng, the Party Secretary for Shanghai and widely viewed as a member of Jiang Zemin’s faction, the Shanghai Clique.

We should also note that Liu He, the Harvard educated economist and one of Xi’s closest advisers on economic liberalization, has also been promoted to the Politburo, yet another strong voice for liberalization and a Xi ally.

But Xi’s political consolidation is not so much a display of superhuman statecraft, but more as the lack of alternative that the CCP bureaucracy as a whole faces. After decades of breakneck growth, Chinese society is strained to its limits. Rampant inequality and injustice, pollution, stress, and enormous economic contradictions and indebtedness are pulling society in dozens of different directions and threaten the entire system. The bureaucracy is striving to establish a monolithic and supremely powerful political control with which to quash any dissent or strike wave whilst implementing tricky pro-market reforms. To this end, a team of technocrats and enforcers completely subordinated to Xi’s agenda of orderly marketization has been ruthlessly imposed by Xi against all other factions.

The bourgeoisification of the CCP

Given that the Chinese capitalist class has emerged through nurturing by the Stalinist state apparatus, it has no choice but to adapt the Communist Party to its own needs, a task which the CCP leadership has encouraged and participated in. With each passing year, the CCP’s class composition becomes more and more bourgeois.

The congresses of the CCP, taking place once every five years, provide a good way of measuring these changes. Besides the hundreds of delegates that are businessmen, there were 27 delegates formally representing private enterprises. Among them are not only CEOs or presidents of massive Chinese companies, but also representatives from multinational corporations such as Samsung and KPMG. People.com.cn itself acknowledges that private enterprises make up more than 60 percent of China’s GDP and create 90 percent of all new jobs, in order to justify their representation and to conclude that the views of these 27 delegates’ are gaining more and more weight.

At the same time the wealthiest 100 members of the National People’s Congress (China’s parliament that meets annually in the Spring) saw their wealth increase by 64 percent during Xi’s first term, having a combined fortune of $507 billion US dollars, similar to the GDP of Belgium and dwarfing the wealth of the US Congress (itself hardly known for its spartan or anti-capitalist qualities). The recent embrace of party organizations by large private enterprises is further proof that the Chinese bourgeoisie has thoroughly penetrated and adapted the CCP for its purposes. The 2017 CCP congress indicated that the party is to be further opened up to capitalist elements as marketization deepens.

Official media openly and repeatedly stress the fact that the delegates at this year’s congress were from more professional and higher educated backgrounds, which is a euphemistic way of saying they are richer and, inevitably, more pro-capitalist. The entrance of private capitalists into the Party and State structures is hardly a new and surprising phenomenon, but one that stretches back to the late 1990’s when capitalism’s restoration was approaching completion, as the 2010 study Sources of social support for China’s current political order: The “thick embeddedness” of private capital holders by Christopher McNally and Teresa Wright already proved:

“In fact, a nationwide study conducted in 2000 found that 20 percent of all private entrepreneurs were CCP members (Li, 2001, p.26), while by 2003 Party membership had climbed to nearly 34 percent (Tsai, 2005, p.1140). Party membership appears to be particularly prevalent among medium and large private enterprise owners: in surveys from the late 1990s, 40 percent were already Party members, and more than 25 percent of the remainder had been targeted by the CCP and wanted to join (Dickson, 2003, p.111). By way of comparison, as of 2007, only 5.5 percent of the entire population was a CCP member (Xinhua, 2007).”

“Private entrepreneurs thus are widely believed to comprise the highest percentage of CCP members per capita of any social sector.”

The growing weight of the capitalist class within the Party that we see today under Xi is an established and indisputable fact. It is part and parcel of what the party and the state has become. The CCP is not only unable to resist this, but embraces it as the market’s influence over society becomes all-embracing.

For now the bureaucracy, especially those at the top, can maintain a degree of independence from the bourgeoisie, who nevertheless are accentuating their influence within the party. But just as capitalist power and influence swells, the crisis of capitalism is creating the conditions for the also increasingly powerful working-class to move into more militant struggle against capitalism. It is for these reasons that Xi is being compelled to take bonapartist measures to balance the Party between the working-class and the capitalist class in attempt to manage the contradictions.

What does Xi’s strongman regime mean?

As has been widely reported, the closing ceremony of the Congress saw Xi Jinping’s ‘theory’ of ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era’, nicknamed ‘Xi Jinping Thought’, being voted into the Party Constitution. This makes him only the second Party leader to have his own ‘thoughts’ written into the Constitution while still alive and serving as President, the first one being Mao himself. This, combined with the high profile elimination of prominent CCP bureaucrats (‘catching tigers’), indicates that something is afoot in China.

As has been widely reported, the closing ceremony of the Congress saw Xi Jinping’s ‘theory’ of ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era’, nicknamed ‘Xi Jinping Thought’, being voted into the Party Constitution. This makes him only the second Party leader to have his own ‘thoughts’ written into the Constitution while still alive and serving as President, the first one being Mao himself. This, combined with the high profile elimination of prominent CCP bureaucrats (‘catching tigers’), indicates that something is afoot in China.

What do these dramatic changes and maneuverings mean? Many Stalinists in the West are drawing hopeful conclusions that Xi is Mao reincarnated, and that he will completely reverse China’s capitalist backsliding and return to the glory days of the nationalized planned economy, yet this is obviously fanciful, as the above figures on party composition show. So what is behind the scheming and why is Xi’s thought written into the constitution?

It is nothing short of a strengthening and concentration of the bonapartism of the Chinese state. Bonapartism is when the state gains a large degree of autonomy from even the ruling economic class. This is commonly referred to as a dictatorship, but the meaning is more scientific and exact than that, because it specifies that this dictatorship is achieved by balancing and playing off the two main classes against each other. Although this deprives the bourgeoisie of direct political power, the greater repressive powers of the state are used to defend, in the final analysis, the capitalist economic system. Bonapartism saves capitalism from the capitalists themselves.

This is exactly what is going on in China. In the past period we have seen many massive Chinese companies setting up Communist Party cells under pressure from the state, which led many to believe that this represents a growth of state interference in, and even hostility to, the functioning of capitalism. Some have speculated that this is evidence of a plan for re-nationalization. Indeed, in 2016 alone, the proportion of private enterprises with a party cell grew by 16.1 percent.

While company party cells do indeed place the management under some sort of political leash, they are to a much greater degree organs of direct control over the company’s trade union (should there be one), as by law all company unions are placed under the leadership of the company’s party cells. The proliferation of party cells also offer the management themselves a channel to participate in the Party’s political life, which affords them both influence and a degree of political protection against, say, a trial for corruption. Workers who are party members also automatically enjoy perks and are prioritized for promotions, thus creating a layer of privileged workers to set against their colleagues. Such cells are therefore used to politically control both classes, but much more so the working-class, to the benefit of the capitalist class.

The party does respond to grievances from the working-class, but very strongly clamps down on any attempt at resolving labour disputes outside of the allowable framework. What it can tolerate least of all is independent and coordinated militant activity from the working-class. The system of ‘Shang Fang’ or grievance reporting to the government has been expanded and monitored by the State Bureau of Letters and Calls. In the last 5 years Sichuan province alone claims to have processed 3.8 million filings, which could result in sackings of reported local officials or pressure on private companies to pay their workers.

On the other hand, independent labour activists such as those active in the Guangdong factory strikes at the end of 2015 are immediately arrested. The national Walmart workers’ strike in 2016 also received tacit approval from the official company union, who simultaneously accused the leadership of the strike of being under foreign influence. The state leans on working-class anger in an attempt to manage the contradictions of capitalism, especially as it wants to see workers getting higher wages in order to boost domestic demand in the economy. It also needs to show that it responds to their grievances, since its claim to legitimacy in building capitalism is that it is raising the living standards and improving the lives of the masses. But it will tolerate no independent activity of the working-class.

The Party has been able to maintain its dominant position within society chiefly because Chinese capitalism is completely unable to develop itself without the nurturing of a strong state, a state which in fact is responsible for the very existence of capitalism in China. This is why in the absence of a severe economic crisis, the CCP can still balance itself between the classes while at the same time developing Chinese capitalism.

A severe economic crisis, however, is just what is in store for China after decades of growth. Xi Jinping and the Chinese ruling class know this is coming. Try as they may to put off the evil day, deep down they know it is inescapable. They are well aware of the sharp increase in debt. It is primarily these deep-seated economic problems, and the exacerbation of the class struggle they will bring, that have inspired Xi’s concentration of power: the elimination of rival factions through the anti-corruption campaign, the intensification of so-called ‘Marxist’ propaganda painting Xi and the CCP as champions of the working masses, and the enormous expansion of the security apparatus to unprecedented levels.

The real meaning of the anti-corruption campaign

In the past four years Xi has shaken to the core the entire party bureaucracy with his anti-corruption campaign, which created an impression that no one within the Party, no matter how powerful, is exempt from Party discipline. The high profile anti-corruption campaign indeed removed some very powerful party and military leaders, most notably ex-Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang who had enormous control over the state-owned oil enterprises, and high ranking general Xu Caihou. Ahead of the 19th Congress we also saw the largest amount of Central Committee members being expelled, the most prominent of which was Standing Committee hopeful Sun Zhengcai. The Army’s Chief of Staff Fang Fenghui was also reportedly placed under investigation.

We must understand that the purging of certain bureaucrats does not represent a fundamental change in the policy of the state so much as the elimination of those that may impede Xi’s ability to enforce his policies. Xi fears that in the coming crisis, the existence of any factions in the bureaucracy may lead to splits or undermine the party’s central authority in a situation in which it will already be strained. An economic or social crisis will test the old regime to the limits, so it can ill afford any unreliable elements.

Sun Zhengcai, as the previous governor of Chongqing, was a telling example of a prominent bureaucrat whose corruption was so rampant and widespread that it threatened the Party and its capitalist programme. Shortly before being placed under investigation ahead of the Party Congress, it was revealed that Sun had provided an obscure IT company with the capital and connections to represent themselves in the name of the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative to Lithuania and Kazakhstan’s Central Bank chiefs, hoping to reap immense profit by doing so.

Xu, a leading general in the army, was found guilty of trading promotions for cash. Fang Fenghui, army chief of staff, was accused of maintaining close relations with US military figures. Most prominent of all, Zhou Yongkang, who was on the Standing Committee, was found to have used his position at the top of the China National Petroleum Corporation to extract billions in bribes and enrich family members, Prior to his investigation, Xi met with prominent party leaders and ex-leaders, most notably Jiang Zemin, to sound them out and make the case that his corruption and decadence threatened the stability of the whole system.

Rampant corruption is an inherent weakness in totalitarian state bureaucracies such as China’s. There are also no democratic “safety valves” for society’s enormous contradictions to let off steam. Competing capitalist interests need to gain influence within any state, not least one as powerful as China’s. The fiction of unanimity and harmony in the state apparatus is constantly threatened by these factors. Xi has identified this and is attempting to stamp it out in a giant and ultimately unwinnable game of ‘whack-a-mole’.

This extends not just to the top of the bureaucracy but throughout the party. The CCP, being the only party and fused with the state, concentrates within itself a variety of social forces. Anyone wishing to climb the career ladder joins the party, and thus one function of the party is to serve as an elaborate networking organisation. It is for this reason that in the last year or so, the CCP has begun to set stricter criteria for membership in an attempt to stop the rot.

“Research suggests that many of these youngsters see membership not as a vocation but as a shortcut to stable employment (many jobs in public service and government-linked companies are reserved for party members), or simply as one more way of proving their superiority over classmates. In 2015 a survey at one middling university found that only one-sixth of those applying to the party were doing so to “serve the people”, and that only a quarter could say that they had a ‘very strong’ desire to be accepted.” (The Economist, 23.11.17).

The central bureaucracy is more representative of the parts of China where capitalism is more developed, against other regional bureaucrats that are more reliant on propagating and controlling regional state enterprises. The state’s authority constantly tends to fray at the edges. The party leadership fears that rampant corruption, especially in regional provinces, could expose cracks in the regime that the masses could use to their advantage, igniting a mass movement that could quickly threaten the whole regime. This is why they have preemptively made examples of a large number of corrupt officials both to discipline the wider apparatus and to create the illusion that not all of the bureaucracy is a parasite on the working-class, but only the corrupt few. Simultaneously, the anti-corruption scandal also eliminates Xi’s political rivals.

Market economy with CCP characteristics

Xi’s highly-anticipated speech was three and a half hours long, and its sheer length became a point of focus for many in the international media. However at least three hours of it was filled with empty platitudes such as “our party must fight for people’s livelihood”; “we must realize the Chinese Dream and the great revival of the Chinese nation”; “we must be strict on ourselves and fight corruption”; as well as bare faced lies such as, “in our country, the ruling class is the coalition of workers and peasants”; “we worked hard to study and develop Marxist theory.”

Xi’s highly-anticipated speech was three and a half hours long, and its sheer length became a point of focus for many in the international media. However at least three hours of it was filled with empty platitudes such as “our party must fight for people’s livelihood”; “we must realize the Chinese Dream and the great revival of the Chinese nation”; “we must be strict on ourselves and fight corruption”; as well as bare faced lies such as, “in our country, the ruling class is the coalition of workers and peasants”; “we worked hard to study and develop Marxist theory.”

Only about half hour of the speech actually had any substance, and within which he spent the majority of the time talking about deepening the marketization and liberalization of the economy (with occasional points on the need to also have strong regulatory mechanisms especially in the housing market), while bolstering welfare spending. He also outlined plans to strengthen the central government’s power in implementing policies nationally as a way of affirming the party’s “political leadership” over the country, as well as a halt to privatization of large state owned industries, preferring to manage them in a way that is “competitive in the market.” Carefully chosen sound bites such as “We must increase globalization, improve on liberalization and opening up” and “Deepen commercial reform, smashing administrative monopoly, prevent market monopoly, perfect market monitoring system” sum up the direction in which Xi wants to take China.

Despite the CCP’s utopian promise of building a market economy without systemic risks, China’s capitalist economy cannot escape from the fundamental crisis of overproduction inherent in capitalism. This is manifested in the slowdown of growth since around 2014, the sharp increase in debt, as well as occasional stock market shocks. The party, unable to ignore these facts, is forced to admit via Xinhua news that it is aware of the problems and will find ways to stimulate more private investment.

The CCP is seeking to accomplish this by first abandoning the restrictions it previously placed on foreign enterprises to operate in China. As Xinhua promised, “Any enterprises that are registered within the border of our country will be viewed in the same way and treated the same. We will insist on a new mode of managing foreign investments based on the new record-keeping based system, further elevating the convenience in investment.” Record-keeping system in this case refers to an overhaul of the legal steps foreign enterprises have had to go through in order to legally operate, which typically takes one to three months.

China is well known for placing a lot of restrictions and requirements on foreign companies, such as that they must enter into joint ventures with Chinese companies and share their technology with them. The new proposed system will drastically simplify the process of registration for foreign enterprises and allow them to come into China’s market faster. It also promises the state will not interfere with individual corporations’ decisions in how they allocate their investments. This indicates the CCP now has sufficient confidence in the larger Chinese enterprises to compete with foreign companies without the assistance the state previously provided, but also that they feel an urgency to attract foreign investors back into China to keep the growth rate afloat.

Alongside this internal strategy, the Congress outlined plans for an external strategy to try and delay the crisis of overproduction in the Chinese economy : a more aggressive imperialist policy of investment in other countries by and for Chinese companies. The One Belt One Road policy (which we have analysed previously in Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte leaning towards China – why? and Pakistan: The ever growing power of China) is the biggest act of economic diplomacy since WWII and an unmistakable sign of burgeoning Chinese imperialist aspirations as a means to temporarily overcome the brewing crisis of Chinese capitalism.

China now produces half of all the world’s steel and aluminium. Shenzhen is rapidly becoming a worldwide centre for the tech industry. In every way, the vast expansion of China’s productive forces has laid the foundations for an enormous crisis of overproduction (China and the World Economy in 2016: “Sell Everything”).

In reality, the Chinese economy is long overdue a crisis, which should have arrived with the 2008 world crisis. As we know, China rescued world capitalism in that fateful year with a vast fiscal stimulus: the biggest in world history. But that was achieved by capitalist means, i.e. with debt, and as Marx and Engels explained in the Communist Manifesto, such methods only create bigger crises in the future. The total debt in the Chinese economy has quadrupled to £22tn since 2008!

In a statement, the IMF has pointed out that “debt as a proportion of gross domestic product would rise from 235 percent to almost 300 percent by 2022. Previously, the Washington-based IMF – which publishes annual reports on its member countries – had said debt would peak at 270 percent of GDP…China needed three times as much credit in 2016 to achieve the same amount of growth as in 2008…Since 2008, private sector debt relative to GDP has risen by 80 percentage points to about 175 percent – such large increases have internationally been associated with sharp growth slowdowns and often financial crises….China now has one of the largest banking sectors in the world. At 310 percent GDP, China’s banking sector is above the advanced economy average and nearly three times the emerging market average.” (The Guardian, 15.8.17).

After decades of staggering growth, China has changed profoundly. All of the contradictions of capitalism have embedded themselves into the fabric of China, and in turn China is embedded at the centre of a crisis-ridden world economy. The slowdown in the economy, the growing discontent and militancy of the working-class, the explosion of debt to totally unsustainable levels, and the embarking onto imperialist ventures, all these express the complexity of Chinese society and the inevitability of an immense crisis. Running China on this basis has become like spinning plates, and Xi needs all hands on deck to make sure those plates stay spinning in the interests of capitalism. That is the lesson of the 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party and the subordination of the Party to Xi’s will.