Modern scientific research has

identified the major physiological, neurological, and genetic

differences between humans and our biological ancestors. In particular,

it has been found that the human brain is qualitatively different in

terms of the development of the parts of the brain that control abstract

reasoning, social behaviour, and manual abilities.

Modern scientific research has

identified the major physiological, neurological, and genetic

differences between humans and our biological ancestors. In particular,

it has been found that the human brain is qualitatively different in

terms of the development of the parts of the brain that control abstract

reasoning, social behaviour, and manual abilities. This discovery is

yet more evidence in favour of the explanation that Frederick Engels

gave for the evolution of humans in his essay “The Part Played by Labour

in the Transition from Ape to Man”.

This

latest research, by Dr Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute for

Evolutionary Anthropology, was reported in a recent edition of The Economist (4th February 2012), which states that:

“Dr Paabo and his colleagues focused their examination, just published in Genome Research,

on two parts of the brain. One was the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,

which is the seat of abstract reasoning and social behaviour – things

that humans are particularly good at. The other was the lateral

cerebellar cortex, which is more to do with manual abilities.”

Compare the above to this paragraph from Engels’ work, written in 1876:

“First labour, after it and then with it speech – these were the two

most essential stimuli under the influence of which the brain of the ape

gradually changed into that of man, which for all its similarity is far

larger and more perfect. Hand in hand with the development of the brain

went the development of its most immediate instruments – the senses.”

Unfortunately Engels is very rarely given credit for this analysis, which was incredibly advanced for his time.

The part played by labour

In his essay “The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to

Man”, Engels explains that the decisive step in the evolution of humans

was the adoption of an upright posture. This move from walking on four

feet to two was the result of changes in the environment, which forced

some primates from the forests to the ground below, where they were

required to travel long distances in the search for scarce food

resources. This transition to a bipedal, upright stance freed up the

hands and allowed them to develop a range of flexible functions.

Through the interaction between these proto-humans and their

surroundings, the hand developed new strength and dexterity. This, in

turn, allowed for these early ancestors of ours to manipulate nature in

increasingly complex ways. For example, the development of opposable

thumbs allowed for hands that could grasp and grip objects, whilst the

development of the muscles and ligaments in the hand allowed for finer,

more intricate and detailed tasks to be carried out. As Engels explains:

“Thus the hand is not only the organ of labour, it is also the

product of labour. Only by labour, by adaptation to ever new operations,

through the inheritance of muscles, ligaments, and, over longer periods

of time, bones that had undergone special development and the

ever-renewed employment of this inherited finesse in new, more and more

complicated operations, have given the human hand the high degree of

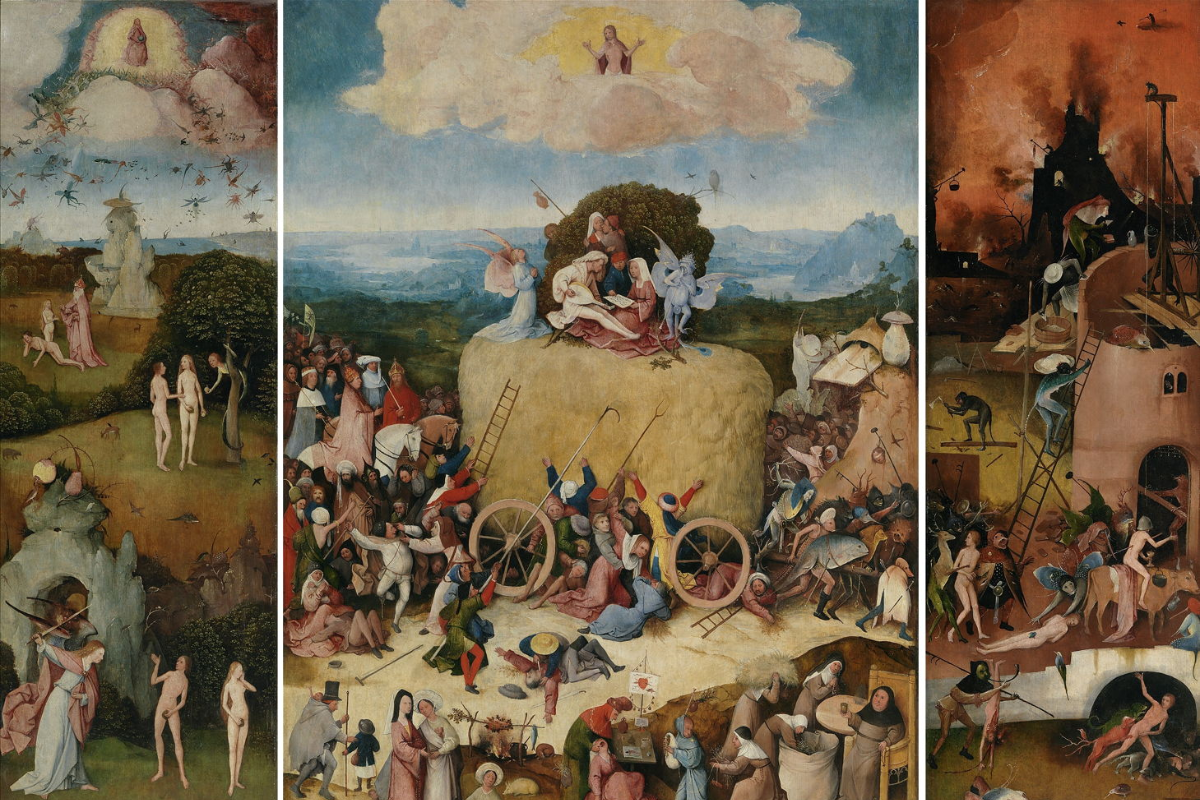

perfection required to conjure into being the pictures of a Raphael, the

statues of a Thorwaldsen, the music of a Paganini.”

The development of the hand was a qualitative leap forward in terms

of the ability for these early humans to manipulate their surroundings.

Through the development of the hand, more complex tasks could be

implemented and more advanced tools could be fashioned. Whilst other

animals may “use tools”, it is mostly in a simplistic, accidental, and

unplanned manner. Humans are qualitatively different, however, in that

they actively and consciously make tools in a planned manner in order to

carry out complex operations and alter nature.

As Marx and Engels explained in their various works on historical

materialism, the original contradiction in human society was not between

man-and-man, but between man-and-nature. By studying the development of

humankind and society through the ages, Marx and Engels saw that there

are general laws that can be observed, the clearest of which is the

development of the productive forces over time. In other words, we can

see, over the course of history, an ever increasing ability for

humankind to manipulate nature and to therefore free itself from the

confines of nature.

It is this ability to manipulate nature for our own ends that separates humans from all other species. Engels remarks that:

“In short, the animal merely uses its environment, and brings about changes in it simply by its presence; man by his changes makes it serve his ends, masters

it. This is the final, essential distinction between man and other

animals, and once again it is labour that brings about this

distinction.” (emphasis by FE)

Development of the brain

Engels explained that the development of one part of the body, such

as the hand, would have a dialectical effect on the rest of the body,

including the brain and the senses:

“But the hand did not exist alone; it was only one member of an

integral, highly complex organism. And what benefited the hand benefited

also the whole body it served…“…the body benefited from the law of correlation of growth, as

Darwin called it. This law states that the specialised forms of separate

parts of an organic being are always bound up with certain forms of

other parts that apparently have no connection with them…“Changes in certain forms involve changes in the form of other parts of the body, although we cannot explain the connection.”

Some evolutionary scientists lay emphasis for the development of

humans in the brain, the explanation being that the brain of our early

ancestors gradually increased in size, leading to superior intelligence

and the capacity for language, tool-making, etc., which in turn led to

the dominance of the human species over others.

Engels turned this argument on its head, and explained that it was

not the larger brain size and superior intelligence that led to the

development of tools and language, but vice-versa. Through the

development of the hand, and the increasing complexity of tasks that

this allowed, the brain was stimulated. In addition, the new upright

posture also allowed for a heavier skull and brain to be carried.

The dialectical relationship between the hand and the brain meant

that as the hand developed, the brain developed also, which in turn led

to greater intelligence. This dialectical relationship, however, is not

confined to the hand and the brain, but exists between humans and their

surroundings also. Through the development of the hand and tools, early

humans were able to interact with their surroundings to an ever greater

degree – to manipulate their environment. Through this greater level of

interaction, over time, early humans could begin to examine and

understand the world around them in a more “scientific” manner.

By manipulating nature, we gain an understanding of nature itself.

Like the development of the hand, the development of thought is also the

product of human activity – i.e. labour. Through interacting with and

acting upon their surroundings, early humans could begin to abstract and

generalise their experiences to a higher level. Rather than seeing each

individual action and outcome as an isolated event, general laws and

processes could be understood. Through our repeated actions on our

surroundings, we begin to see cause and effect. Unexplained phenomena

become understood processes; mankind transforms the “thing in itself” to

a “thing for us”.

In turn, the ability to abstract and generalise leads to the ability

to develop even more advanced tools. We gain an understanding of

processes by generalising our experiences of many repeated actions and

outcomes, comparing what makes them similar and what makes them

different. For example, by repeatedly smashing one stone against

another, an early human would gradually come to understand the force and

angle that was needed in order to create a sharp tool for hunting. In

this way, rather than being at the mercy of nature, humankind becomes

master of it, and is able to manipulate it to a greater and greater

degree.

By interacting with our surroundings, we become more aware of them.

We begin to gain a sense of self-awareness and self-consciousness. A

similar process to the early development of humans is seen in the early

development of children, with the progression from the unconscious to

the conscious through their interaction with the environment. We begin

to understand and generalise the experiences of the past and thus we are

able to plan for the future.

However, despite our greater scientific understanding nowadays, the

brain and the mind are still imbued with a mystical quality by some.

Throughout history, the origin of human ideas and thought has always

been the subject of debate. Some people claimed (and still claim) that

we might have “innate” knowledge of some things. But all knowledge is

gained through practice and experience of the material world. Our

thoughts and ideas do not exist in a separate realm, but are an

imperfect reflection of the physical world in which we live.

Mind and matter were said by many philosophers to be separate

entities. But the mind is simply the result of the complex interactions

and processes taking place within the brain. Consciousness is nothing

more than matter that has reached a certain level of organisation and

development – matter that has become aware of itself – as Engels

comments in his essay, “Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German

Philosophy”:

“Our consciousness and thinking, however supra-sensuous they may

seem, are the product of a material, bodily organ, the brain. Matter is

not a product of mind, but mind itself is merely the highest product of

matter. This is, of course, pure materialism.”

The role of language

Alongside the development of the hand, Engels attributes the growth

of the brain to the role of language and speech, which, like the hand,

were also the product of labour. Engels explains that language is the

result of the development of social production and organisation, which

led to the need for greater levels of communication:

“The development of labour necessarily helped to bring the members of

society closer together by increasing cases of mutual support and joint

activity, and by making clear the advantage of this joint activity to

each individual. In short, men in the making arrived at the point where they had something to say to each other.” (emphasis by FE)

Whilst other animals clearly communicate through noises, it is only

in humans that we see the complexities of language, with clearly defined

words, grammar, and syntax. This is the result of the social mode of

production, which requires a higher level of communication as a result

of the greater level of social interaction between individuals.

Language itself requires a certain level in the development of

abstract reasoning and thought, since words themselves are used to

represent abstractions and generalisations of complex, imperfect objects

and processes in the real world. For example, we come up with the word

“circle” to describe the general idea of a round object, which we have

observed and experienced in a variety of forms in the real word.

Similarly, the word “mammal” is used to represent the abstract category

of species that share certain characteristics.

Whilst language requires the ability to abstract and generalise, the

emergence of language leads, in a dialectical manner, to the further

development of abstract reasoning, by allowing humans to generalise

their experiences. Through the use of internal monologue, more complex

ideas and thoughts can be processed, and humans begin to consciously

plan their actions. In turn, the use of language allows ideas to be

communicated and passed down from generation to generation, creating a

“social memory”, i.e. societal knowledge. As Engels explains:

“The reaction on labour and speech of the development of the brain

and its attendant senses, of the increasing clarity of consciousness,

power of abstraction and of conclusion, gave both labour and speech an

ever-renewed impulse to further development…“…This further development has been strongly urged forward, on the

one hand, and guided along more definite directions, on the other, by a

new element which came into play with the appearance of fully-fledged

man, namely, society.” (emphasis by FE)

Genetic determinism

The great genius of Engels was to give a materialist explanation for

the evolution of humans and their difference from their ancestors. As

explained above, the main thrust of Engels’ explanation lies in

identifying the development of the hand and speech, through labour and

socialised production respectively, as the impetus for the growth and

development of the brain and human intelligence.

The modern research by Dr Paabo mentioned above, whilst seemingly

strengthening Engels’ analysis, is in danger of inverting cause and

effect. As mentioned previously, it is not simply the growth of certain

parts (or the whole of) the brain that leads to the development of

abstract reasoning, social behaviour, and manual abilities, but

vice-versa. The need to survive required greater social intercourse

between individuals, whilst the need to stand upright led to the

development of the hand and increased manual dexterity, which in turn

led to the development of the brain and the increased ability to

abstract and generalise. In other words, the size and structure of the

brain is the product of the interaction between ourselves and our

environment, and also between the brain itself and the other parts of

the body.

The main element in Dr Paabo’s research was in attempting to identify

the specific genes that are uniquely active in human brains but not in

those of other similar species, and thus find the genes responsible for

“making us human”. This is dangerous territory. To think that the

qualities of humans can be reduced to a single set of genes is to reduce

the qualities of all life to a simple, mechanical one-sided genetic and

biological determinism. Humans are not mere mechanical machines and our

genetic code – i.e. DNA – is not completely analogous to the

programming computer code that defines the actions of a robot.

Human DNA is 98% identical to that of chimpanzee DNA, but that 2%

makes a qualitative difference. More importantly, one cannot explain the

qualities of humans – either as individuals or as a species – by simply

comparing their genes against those of our ancestors. We are not simply

the product of our genes, but of the complex, dynamic interaction

between our genes and our environment, including all the various social,

economic, and cultural factors involved.

We are more than the sum of our parts. For example, the human brain

when removed from the body ceases to act as a brain, but merely becomes a

lump of inert matter. Similarly, one cannot ascribe a particular

physical or psychological quality of humans, or of any individual, to a

single gene or even a set of genes. It is the complex interaction

between our entire genetic code and our environment that gives rise to

us as a species with all our qualities.

The mechanical approach of analysing a thing or phenomena in

isolation has nothing in common with the method of dialectical

materialism, which recognises that all things are interconnected, and

that it is these very interconnections that give rise to the qualities

of any one thing. To detach one element of a thing – i.e. one gene in a

human – and analyse it in isolation means losing the connections and

interactions between that element and all the others that give rise to

the various qualities of the thing.

Human nature

The arguments of the biological and genetic determinists stray

perilously close to the ideas of those who talk of an innate “human

nature”, a concept which is used to justify the entire exploitative

nature of capitalism. After all, how can we ever have socialism if we’re

all inherently greedy, selfish individuals?

Dialectical materialism – the philosophical method of Marxism –

recognises that no thing possesses innate properties that are simply

inherent characteristics of the thing itself. All properties are

relations and are relative. For example, a knife does not simply possess

the properties of “sharpness” and “hardness” that allows it to cut. The

properties of sharpness and hardness are relations between the knife

and another object. In relation to butter, a knife is both sharp and

hard; however, in relation to a diamond, a knife is no longer hard and

its sharpness is of no use.

Similarly, Marx explained in Capital that capital itself is not a

thing, but a social relation between things. Money or machinery by

itself is not capital; money or machinery used to exploit labour and

produce a surplus is capital.

Hence there is no such property called “human nature”. All the

qualities of humans are a result, on the one hand, of the interaction

between our genes and our environment, and on the other hand, of our

social relations – i.e. of the relationship between the classes and the

means of production. Greed and selfishness are not inherent qualities of

the human species that arise due to the competition for resources, as

is proclaimed by the Social Darwinists, who seek to indentify these

qualities as an inevitable product of the “survival of the fittest” – a

term that Darwin himself never used. Rather, greed and selfishness are

products of the capitalism system, which thrives on competition between

individuals.

Greed and selfishness are not innate qualities of humans that arise

from a Darwinian struggle for existence, but are qualities that arise

from the struggle between the classes. What’s more, these qualities are

not natural to the working class, who are, in fact, compelled to

cooperate and collectively organise in order to maintain their standard

of living in the face of attacks by the capitalists. Greed is not a

quality of human beings in general, but a reflection of the ideology of

the bourgeoisie, a class whose entire existence is based on greed and

competition.

Unlimited potential

The great leap forward in the evolution of humans was the freeing up

of the hands. With this decisive step, our ancestors freed themselves

from the confines of their genetic code. Early humans were not the

strongest creatures or the fastest hunters, but with the freeing up of

the hands, humankind began to develop tools, thus gaining a great

advantage over all other animals. For the first time in the history of

the earth, a species existed whose evolution was not simply determined

by nature and the given environment. Here was a species that could

change the environment in which it lived.

We have now reached such a point as a species where our understanding

of nature and ability to manipulate it means that we can actually

change the code of life itself through genetic engineering. Meanwhile,

the development of tools has reached such a high level that modern

research is being conducted into mind-controlled machines. The ability

to augment ourselves through genetic design and bio-engineering is now a

real possibility. In this respect, the potential for what we can

achieve as a species goes far beyond what is dictated by our genetic

code.

This unlimited potential, however, cannot be fulfilled under

capitalism. The private ownership of the means of production, with its

constant quest for greater and greater profit, is a great barrier on the

development of the productive forces; of the development of science and

technique. Rather than moving humankind forward, and using the

accumulated knowledge of millennia, capitalism throws millions into

poverty and threatens to reduce us back to a level of barbarism. We will

only be able to use our full potential as a species by democratically

planning our society and using the great productive forces that we have

at our disposal for the good of people, not profit. As a species we have

evolved an immense potential. Our brains are capable of the most

advanced thinking. Capitalism is not the final frontier of human

ability, but a mere stage in a much bigger picture. To move on in a

progressive manner as a species we must first overthrow capitalism and

put an end to the misery that it causes. That means moving forward to

socialism!