In Wage Labour and Capital, Marx sets out, in embryonic form, a theory of capitalist relations of production. This text was published for the first time, in the April of 1849, in Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a newspaper which Marx had founded and was editing in Cologne, following the spread of revolutionary activity from France to Germany in the March of 1848.[1]

Marx published over 80 articles in Neue Rheinische Zeitung, the first edition of which came out in June 1848. The subtitle of this newspaper was ‘organ of democracy’, and, at first, it supported the radical liberals, who were the left wing of the Parliament in Frankfurt, against the King (Friedrich Wilhelm IV). However, in the April of 1849, following counterrevolutionary activity in France and Germany, Marx abandoned the policy of co-operation with the radical liberals and argued for the establishment of an independent workers’ party. In response to the new revolutionary line, the Government shut down the newspaper in the May of 1849, at which point Marx returned to Paris.

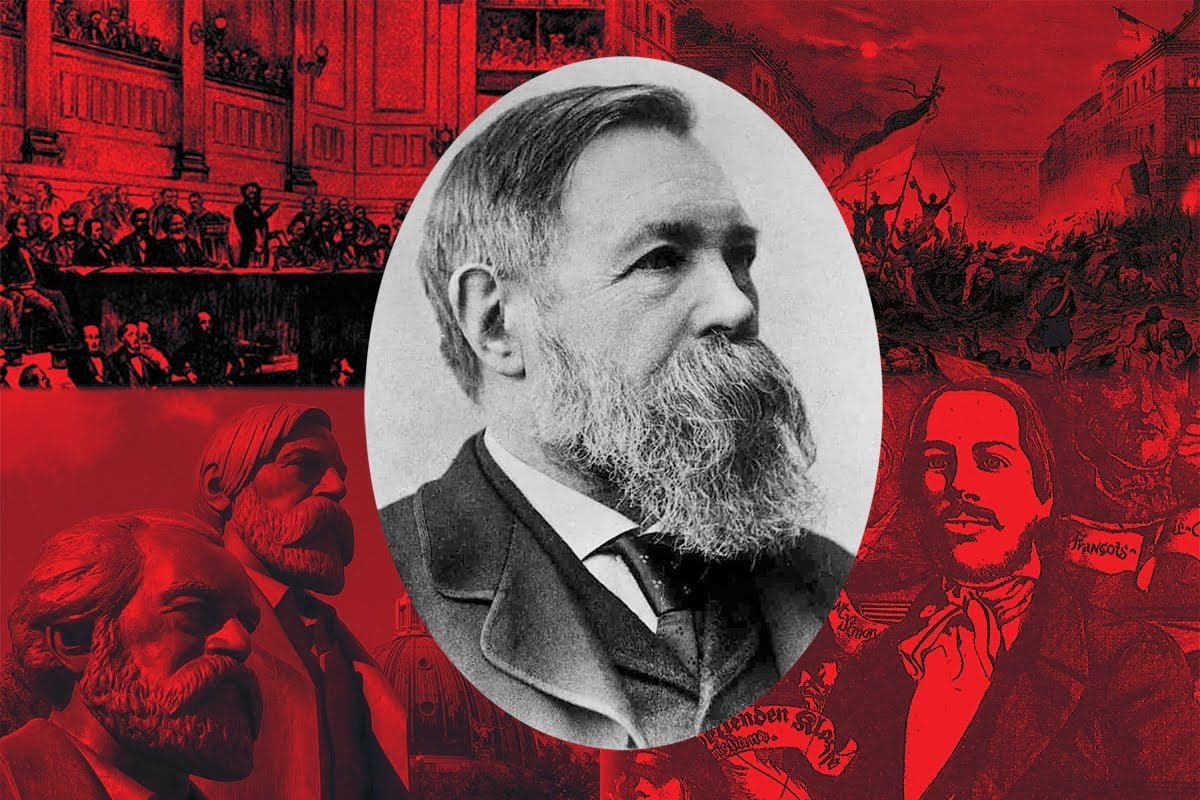

Marx had delivered the five articles which were published in Neue Rheinische Zeitung as a series of lectures to the German Workers’ Society in Brussels, in the second half of December of 1847. Marx and Engels had founded the Society to educate those German workers who had migrated to Belgium in search of higher standards of living.[2] However, in February of 1848, following the outbreak of revolutionary activity in France, the Belgian police arrested and deported the members of the Society, and Marx was forced to move to Paris. Thus, Marx was precluded from publishing Wage Labour and Capital in Brussels in the February of 1848, as he had intended.

The significance of Wage Labour and Capital is that it is Marx’s first, systematic exposition of his theory of the economic relations of capitalist society. In the articles, he introduces ideas – such as the necessity of co-operation in production, the relative impoverishment of the working class, and the concentration of capital – which he would develop to a much higher level in later works, especially Capital. In short, Marx gives us a popular outline of the economic relations that constitute the material conditions for class struggle in capitalist society.

However, although the articles that were published in Neue Rheinische Zeitung are based on the lectures that Marx had delivered to the German Workers’ Society, they do not encompass the entire content of these lectures.[3] Moreover, Engels published an edition of Wage Labour and Capital in Berlin in 1891, having amended the text to bring the terminology into line with the development of Marx’s thinking after 1849. In the introduction to this edition, Engels writes:

Marx, in the forties, had not yet completed his criticism of political economy. This was not done until toward the end of the fifties. Consequently, such of his writings as were published before the first instalment of his Critique of Political Economy was finished, deviate in some points from those written after 1859, and contain expressions and whole sentences which, viewed from the standpoint of later writings, appear inexact, and even incorrect.

Because Engels intended his edition to be used as propaganda among the workers, he altered the text of the original edition accordingly. He writes:

My alterations centre about one point. According to the original reading, the worker sells his labour for wages, which he receives from the capitalist; according to the present text, he sells his labour-power.

This distinction, between labour and labour power, is the foundation of what is known as Marx’s labour theory of value; without it, it is impossible to understand the origin of surplus value and the laws of development of the capitalist system of production.

In this study guide, we follow the division of the original text that is found in the edition that Engels prepared for publication in 1891.

Preliminary

In the Preliminary, Marx sets out the aim of his work, which is to examine the economic relations of capitalist society and to explain, to the working class, ‘the material basis of the present struggles between classes and nations.’ Marx was compelled to do this, to remove the ignorance and clear up the confusion about economic relations that had been caused by ‘socialist wonder-workers’ and ‘unrecognised political geniuses’, as well as by ‘patented defenders of existing conditions’. Of course, combatting the influence of bourgeois economic thought on the consciousness of the working class is a task in which Marxists must still engage today.

I. What are wages? How are they determined?

The common-sense understanding of the wage, Marx tells us, is that it is a sum of money which the capitalist pays to the labourer ‘for a certain period of work or for a certain amount of work’. In the 19th century, this might have been weaving a yard of linen, if the labourer were paid by the piece, or it might have been weaving linen for a specific number of hours per day, if the labourer were paid by the hour. Herein lies a simple relation of exchange: the capitalist purchases labour with money, while the labourer sells labour for money; or so it seems because, in fact, the capitalist is buying and the labourer is selling, not labour – that is, a particular quantity of work to be done – but labour power – that is, a capacity to work. In the edition of 1891, Engels amends the original text to clarify this point:

But this is merely an illusion. What they [the workers] actually sell to the capitalist for money is their labour-power. This labour-power the capitalist buys for a day, a week, a month, etc. And after he has bought it, he uses it up by letting the worker labour during the stipulated time.

It appears, therefore, that the wage is equal to the value of the work done; and this understanding is expressed in the saying, that we still hear today, ‘a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay’.

By distinguishing between labour and labour power, Marx is distinguishing between the definite product of work, and the capacity to work.

Therefore, the wage is not equal to the value of the work that has been done, or labour, but is equal to the value of the capacity to work – of labour power. Because, under capitalism, labour power can be bought and sold, it is a commodity and thus has value in exchange – that is, it is equal to a certain amount of other commodities, for which it can be exchanged. Wages are the price of labour power.

The claim that the wage is equal to the value of work done is a central tenet of classical bourgeois economics. By distorting our understanding of economic reality, bourgeois economic thought conceals the exploitation of the wage labourer by the capitalist.

What all this implies, Marx tells us, is that ‘[w]ages … are not a share of the worker in the commodities produced by himself. Wages are that part of already existing commodities with which the capitalist buys a certain amount of productive labour-power.’ Wages cannot be ‘a share of the worker in the commodities produced’ because the capitalist pays the wage, not with the money that will be received from selling the finished goods in the future, but with the money that has been received from selling goods in the past. The capitalist uses this money to buy, not only labour power but also raw materials (for example, cotton yarn) and instruments of labour (for example, the power loom). The labourer then works up the cotton yarn into a piece of cotton fabric, which is destined for sale; but whether or not the capitalist finds a buyer for the finished good and whether or not the capitalist sells it at a profit will depend on the prevailing conditions in the market.

Marx also tells us that, although labour power is a commodity, it is a special kind of commodity, when it is considered from the perspective of its use value (as Marx explains further in the first volume of Capital). Because capitalists are buying the capacity to work, they can control the length of its exercise. For example, by increasing the length of the working day, the capitalist increases the duration of the exercise of labour power and, in this way, increases the amount of surplus value that is produced (that part of the total value of a commodity which is beyond what is necessary for the labourer to survive, or the necessary value). In other words, labour power can be used to produce a value in exchange that is greater than its own exchange value.

In the final part, Marx reminds us that generalised commodification of labour power is unique to the capitalist system of production. For example, under the system of slavery, the whole person, not just their labour power, is the property of another person. As Marx puts it, a slave ‘is a commodity that can pass from the hand of one owner to that of another. He himself is a commodity, but his labour-power is not his commodity.’ By contrast, under the system of serfdom, the serf gives to the lord part of their labour power, in the form of either labour dues performed on the land over which the lord has possession or of produce of the land over which the serf has possession. Because, under serfdom, the serf is tied to the land, labour power cannot be a commodity. By contrast, under capitalism wage labourers are not tied to a particular master and are free to sell their labour power to the highest bidder. As Marx puts it, under capitalism

[t]he labourer belongs neither to an owner nor to the soil, but eight, ten, twelve, fifteen hours of his daily life belong to whomsoever buys them. The worker leaves the capitalist, to whom he has sold himself, as soon as he chooses, and the capitalist discharges him as often as he sees fit, as soon as he no longer gets any use, or not the required use, out of him.

Now, it is because wage-labourers are deprived of ownership of the means of production that they must sell their labour power to a capitalist, in order to survive. As Marx puts it, ‘the worker, whose only source of income is the sale of his labour-power, cannot leave the whole class of buyers, i.e. the capitalist class, unless he gives up his own existence.’ This situation has two implications.

- First, economic freedom for any wage labourer is limited by the fact that, although it is possible, in certain conditions, for wage labourers to move between capitalist employers, wage labourers, as a class, are chained to the class of capitalists – contrary to the doctrine of liberalism, which tells us that all men and women are equally free.

- Second, working becomes nothing more than a means to earning a living; that is, people who are forced by social circumstances to sell their labour power to survive are alienated. To be sure, in any society working fulfils a basic human need; but when people lose control over the means and product of labour and labour becomes simply a means to an end, they suffer a loss of fulfilment in life.

Questions for discussion

- What is the wage the price of?

- What is the value of the wage?

- Why is it irrational to speak of the value of labour?

- What is the difference between labour and labour power and why is it important to distinguish between them?

- What is special about the use value of labour power?

- To what extent are wage-labourers free?

- In what ways are wage-labourers alienated

II. By what is the price of a commodity determined?

Having argued that the wage is the price of labour power, Marx considers what determines this price. Because labour power is a commodity, Marx begins by explaining how the price of commodities, in general, are determined. He argues that it is determined in the market, through the mechanism of competition. Marx tells us that competition has three dimensions.

- The first dimension is that of competition among sellers, each of whom attempts to sell their product the most cheaply, to secure the largest share of the market and in the hope of driving other sellers out of business. Hence, competition among sellers has a tendency to depress the price of commodities.

- The second dimension is that of competition among buyers, the effect of which is a tendency for the price of commodities offered for sale to increase. The price tends to increase because each buyer is compelled to outbid all other buyers, to gain possession of the desired commodity.

- The third dimension is that of competition ‘between the buyers and the sellers’ such that buyers ‘wish to purchase as cheaply as possible’, whereas sellers wish ‘to sell as dearly as possible.’ The actual outcome depends on the relative strength of the forces of demand and supply. If demand is greater than the supply, the price will tend to increase; conversely, if supply is greater than the demand, the price will tend to decrease.

Marx summarises these three dimensions using a military analogy:

Industry leads two great armies into the field against each other, and each of these again is engaged in a battle among its own troops in its own ranks. The army among whose troops there is less fighting, carries off the victory over the opposing host.

Having argued that the price of a commodity is determined through the interaction of the forces of demand and supply, Marx asks what determines the supply of a commodity. His answer is that this is determined by the cost of its production, which is measured by the labour time that is necessary to produce it. Marx argues that the price of the commodity fluctuates around this cost, according to the interaction of the forces of demand and supply.

- If the price of a commodity rises above the cost of its production, because demand exceeds the supply, this is an indication that more than average profit is being made. Therefore, capital will flow out of less profitable sectors of industry and into that sector which is more profitable, until the increase in production, and thus supply, brings the price of the commodity below the cost of its production.

- Conversely, if the price of a commodity falls below the cost of its production, because supply exceeds the demand, this is an indication that less than average profit is being made. Therefore, capital will flow out of that sector which is less profitable and into sectors of industry which are more profitable, until the decrease in production, and thus supply, brings the price of the commodity above the cost of its production.

Therefore, the price of any commodity ‘stands always above or below the cost of production’; and, when we look at price fluctuations within a particular sector of industry over time, we find that increases in price are compensated by decreases in price so that, on average, the price is equal to the cost of production.

Moreover, accompanying the fluctuations in the prices of commodities is ‘industrial anarchy’: the construction and destruction of different sectors of industry, in accordance with the inflows and outflows of capital.

Questions for discussion

- What determines the price of a commodity?

- What determines the supply of a commodity?

- What determines the cost of producing a commodity?

III. By what are wages determined?

Having explained the determination of the price of commodities in general, Marx considers the determination of the price of labour power. Because, under capitalism, labour power is a type of commodity, its price is determined in the way that the prices of all other types of commodity are determined. Hence, the fluctuations in the price of labour power (which the classical political economists called the market price of labour power) around the cost of its production are determined by competition between the buyers of labour power, the class of capitalists, and the sellers of labour power, the class of wage labourers; while the cost of production of labour power (which the classical political economists called the natural price of labour power) is the labour time that is necessary to produce it.

Marx argues that the cost of production of labour power is the cost of

- subsistence – that is, of maintaining (or keeping alive) an existing worker

- educating and training workers, so that workers have the appropriate level of knowledge and skill

- replenishing the supply of workers, or reproducing the labour force, because, over time, workers become worn out through the extended use of their labour power and must be replaced.

On average, therefore, the wage is equal to the cost of sustaining, training and reproducing a worker. This is what Marx calls the ‘minimum wage’, which applies to the class of wage-labourers, given the fluctuations of wages above and below the cost of production of labour power.

Questions for discussion

- What determines the price of labour power?

- What determines the cost of producing labour power?

IV. The nature and growth of capital

Having explained the laws which govern the prices of commodities, Marx considers the nature of capital. He argues that, contrary to the doctrine of bourgeois economics, capital is not just a raw material, a tool or a means of subsistence; rather, raw materials, tools and means of subsistence become capital within certain social relations: the relations of production. A spinning jenny, for example, is capital only when it is part of such relations; outside of them, it is nothing but a machine for spinning cotton.

However, a spinning jenny cannot become capital within any kind of relations of production because capital is a specific type of social property: the power to generate exchange value through the preservation and multiplication of existing exchange value. What this means is that the spinning jenny becomes capital only within capitalist relations of production. Under feudalism, by contrast, a spinning jenny would not be capital precisely because feudal relations of production are not the same as capitalist relations of production.

The existence of capital, therefore, depends, not only on the existence of means of production (raw materials and instruments of labour) but also on the existence of a class of wage-labourers – that is, a class of persons who have been deprived of ownership of the means of production and who, in consequence, must sell their labour power to survive.

Finally, Marx draws our attention to the correspondence between the nature of the relations of production and the character of the means of production of a given society. He writes:

the social relations of production are altered, transformed, with the change and development of the material means of production, of the forces of production. The relations of production in their totality constitute what is called the social relations, society, and, moreover, a society at a definite stage of historical development, a society with peculiar, distinctive characteristics. Ancient society, feudal society, bourgeois (or capitalist) society, are such totalities of relations of production, each of which denotes a particular stage of development in the history of mankind.

In other words, it is not an accident that feudal society is a predominantly agricultural society, and that capitalist society is a predominantly industrial society; that is to say, there is a necessary connection, in feudal society, between primitive, self-sufficient production and feudal relations of production just as there is a necessary connection, in capitalist society, between mechanised, mass production for the market and capitalist relations of production.

Questions for discussion

- What is capital?

- On what does the existence of capital depend?

- Why was feudal society predominantly agricultural?

- Why is capitalist society predominantly industrial?

V. Relation of wage-labour to capital

In this section, Marx examines the nature of the relation between the wage-labourer and the capitalist.

For production to be possible, an exchange must occur between the capitalist and the wage-labourer. The capitalists must exchange a portion of their capital for labour power, while wage-labourers must exchange control over their labour power for means of subsistence.

In exercising their labour power under the control of the capitalist, the wage-labourers turn raw materials into commodities and, in this way, they add extra value to those raw materials; as Marx puts it, the wage-labourer ‘gives to the accumulated labour a greater value than it previously possessed.’ If the capitalists sell the commodity at a price which exceeds the cost of its production, they get back, not only the value of the raw materials and labour power consumed, and the depreciation of the instruments of labour, but also a profit. In this way, capitalists increase the amount of capital at their disposal. By contrast, all the wage-labourers can do is to consume the means of subsistence that they receive from the capitalist. They must do this if they are to survive; but they must also replace the commodities which they have consumed by working for the capitalist once again.

What this means is that the social positions of capitalist and wage-labourer are interconnected: that is, the one cannot exist without the other. The capitalists would not be able to make a profit, unless there were a class of people willing to sell to them their labour power, while the wage-labourers would not be able to survive, unless they were able to exchange control over their labour power for means of subsistence. In the words of Marx:

Capital therefore presupposes wage-labour; wage-labour presupposes capital. They condition each other; each brings the other into existence.

The existential interdependence of capitalist and wage-labourer, Marx tells us, is the basis for the claim, which bourgeois economists make, that the material interests of capitalists and wage-labourers are the same. However, bourgeois economists overlook the fact that it is the capitalists, not the wage-labourers, who enrich themselves, when they exploit labour power, and that, because wage-labourers have been deprived of ownership of the means of production, they do not own, and therefore do not control, the wealth that they produce. Moreover, through exploiting more and more labour power, Marx tells us, capitalists increase the size of their capital – that is, their power to produce – and thereby increase their domination of the class of wage-labourers. Hence, despite the increase in the price of labour power that accompanies the expansion of capital, the class of wage-labourers becomes relatively impoverished; and wage-labourers will become even worse off, if the currency depreciates or the price of necessities increases, because, in both cases, the wage-labourers’ real wage – the amount of commodities which can be commanded in exchange for the nominal wage (the monetary expression of the value of their labour power) – falls.

Questions for discussion

- What is the nature of the relation between the capitalist and the wage-labourer?

- Do the interests of capitalists and wage labourers ever coincide?

VI. The general law that determines the rise and fall of wages and profits

The core idea that Marx advances in this section is that the shares of profits and wages in the new value that the wage-labourer produces are inversely related. What this means is that, if real wages increase, in consequence of an increase in the demand for labour power by the capitalists, but profits increase by a larger amount, wages will increase absolutely but will decrease relatively.

Questions for discussion

- What is surplus value?

- Why are wages and profits inversely related?

- What is the difference between surplus value and profit?

VII. The interests of capital and wage-labour are diametrically opposed: effect of growth of productive capital on wages

In this section, Marx argues that a faster increase in profits has to come at the price of a slower increase in wages, so that the relative position of the wage-labourer must deteriorate – that is, the degree of material inequality between the capitalist and the wage-labourer must increase.

What this means is that, as capitalism develops, the dialectical relation of capitalist to wage-labourer becomes contradictory. It is a dialectical relation because the social positions of capitalist and wage-labourer are simultaneously distinct from, yet connected to, one another; and it becomes contradictory, because, as wealth is distributed more and more unequally and as the domination of wage-labourers by the capitalists increases, the two classes develop opposing interests. This dialectical contradiction is the basis for the antagonism, conflict and struggles (both overt and covert) that develop between the two main classes in capitalist society; and it can only be resolved through revolutionary change, wherein the rule of the minority in society – the class of capitalists – is replaced by the rule of the majority – the class of wage-labourers.

Questions for discussion

- Why does the material position of the wage-labourer deteriorate in relation to the material position of the capitalist?

- What is the consequence of the relative deterioration of the material position of the wage-labourers?

VIII. In what manner does the growth of productive capital affect wages?

In this section, Marx considers the effect, on wages, of increasing competition among capitalists. As the number of capitalist enterprises increases, so does the intensity of the competition between them. Hence, to survive, each enterprise has to increase its share of the market by selling at a price below that of its competitors. But to sell more cheaply, it is necessary to reduce the cost of production, or what is the same thing, to increase the productive power of labour.

The productive power of labour can be increased, Marx tells us, by replacing labour power with machines and by extending the division of labour. To the extent that the capitalist enterprise is successful in reducing the cost of production by these means, it will be able to sell at a price just below that of its competitors and thereby capture a larger share of the market. Note that

- capturing a larger share of the market is a necessity, if the capitalist is to be compensated adequately for selling at the lower price and is to remain strong enough to repeat this process and stay in business;

- repeating the process is a necessity because, once competitors catch on and reduce their costs of production by the same means, the average price of the commodity over which they are competing will fall. In short, to avoid ruin, each capitalist enterprise is forced to sub-divide and mechanise the labour process continually so that with increasing productivity comes the continual transformation of the means of production.

We can now understand why capitalist enterprises fight each other in the courts over patent rights, because this is a way of holding off the threat of competition and protecting market share; and we can also understand why capitalist states fight wars, because this is a way of expanding the size of the market for capitalist enterprises and thereby enabling them to realise the value of what they produce on a mass scale.

To the extent, though, that the commodities whose price is falling, in line with the fall in the cost of production, are necessary goods and services, the real wages of the labourers will increase, other things being equal. This is because workers’ have stayed the same, whilst the price of things they buy has decreased.

Questions for discussion

- How can capitalists increase their share of the market?

- What is the consequence, for the wages of the labourers, of an increase in productivity?

IX. Effect of capitalist competition on the capitalist class, the middle class and the working class

In the final section, Marx considers, further, the effect on wages of the concentration of capital. The effect of the increase in the division of labour and of the mechanisation of the labour process, for example, is an increase in the degree of competition among unskilled wage-labourers. This is because, as the labour force is continually sub-divided and as skilled workers are continually replaced by machines

- the demand for skilled labour power decreases, in relation to the demand for unskilled labour power

- the supply of unskilled labour power increases, because skilled workers who have been thrown out of skilled jobs now must compete with unskilled workers for unskilled jobs

- the cost of production of labour power, on average, decreases, because unskilled labour power is less costly to produce than skilled labour power.

In these conditions, wages tend to fall, with the result that those in employment have to work, either longer hours or at a greater intensity, to earn enough to survive.

The degree of competition among wage-labourers is amplified as a result of the ruination of

- the small-scale industrialists, who cannot compete with the larger, more efficient industrialists, as the supply of goods and services increases

- the small-scale shop keepers, who are unable to compete with large-scale ones.

In short, another consequence of the concentration of capital is the proletarianization of the middle classes – the petty bourgeoisie.

The result of increasing competition among capitalists and among wage-labourers is that crises of overproduction become more severe and frequent. In particular,

- as capital expands, the necessity to expand the size of the market, to accommodate the increase in the productive power of labour, intensifies because, with downwards pressure on wages, labourers are increasingly unable to purchase all the commodities that they produce;

- each time a new market is exploited, to accommodate the increase in the productive power of labour, there is one less market to exploit for when the next crisis develops;

- crises of overproduction cannot be overcome permanently because, as the capitalist system of production develops, it becomes contradictory and therefore prone to crises of overproduction. Indeed, the only means whereby crises are overcome merely lay the basis for the next crisis to be even bigger.

Questions for discussion

- What is the consequence, for the wages of the labourers, of an increase in the division of labour and in the mechanisation of the labour process?

- What are the consequences, for the capitalist system of production, of increasing competition among capitalists and among wage-labourers?

Notes

[1] Before he moved to Cologne, Marx lived, briefly, in Paris, after he had been expelled from Belgium at the outbreak of revolutionary activity in France in the February of 1848.

[2] The largest and best organised group of these workers established the Communist League in London, and it was the Communist League for which Marx and Engels wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party. The leading members of the German Workers’ Society were also members of the Brussels branch of the Communist League.

[3] The concluding lectures exist as a document entitled Wages, which Marx did not have time to prepare for publication but which has been published by Lawrence and Wishart in Volume 6 of the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.