Daniel Morley explores the super-exploitative conditions that are now commonplace across the multi-million dollar video games industry. But games workers are beginning to organise and fight back.

If asked what is the least proletarian profession, many might list that of ‘video game designer’ pretty close to the top. Until quite recently, that opinion might well have been shared by a majority of game designers themselves. But now this is changing rapidly. A snowballing of awareness is taking place about the extreme exploitation that the video games industry is based upon.

This wider awareness is being driven by a huge development in the class consciousness of workers, especially young workers – both in the industry itself, and in society generally. A new campaign called Game Workers Unite is fighting for the unionisation of the industry. This is a badly needed and long overdue campaign.

Blood, sweat, and tears

The past few weeks, in particular, have seen an explosion of awareness on this issue, surrounding the release of the biggest game of the year, Red Dead Redemption 2.

The past few weeks, in particular, have seen an explosion of awareness on this issue, surrounding the release of the biggest game of the year, Red Dead Redemption 2.

In an interview with New York Magazine intended to promote the game, its lead writer and vice president of creativity at Rockstar Games, Dan Houser, bragged about working 100 hour weeks on the game.

Houser obviously thought these comments would help it to sell, by showing to consumers how much blood, sweat and tears went into it. Like so many bosses in recent years, he completely misjudged the mood in society and in his own workforce. Instead of praise, he was met with a wave of indignation and protest that has now put the entire industry under the spotlight, giving confidence to workers to express their anger and determination to put an end to the industry’s appalling conditions.

Rockstar Games was immediately forced onto the defensive. Houser himself clarified that these 100 hour weeks were confined only to himself and three other lead writers. He stressed that at Rockstar there is no mandatory overtime; employees (aside from heroic martyrs such as himself) don’t work anything like 100 hours a week. To back this up, Rockstar made available to journalists their own statistics for average weekly hours across the company.

The statistics show that the average weekly hours worked over the past year have been about 45. This is only just short of the EU’s maximum of 48. So by itself this represents intense exploitation, especially given that this is not the top end but only the average.

But it is obvious that these statistics (which we have verifying, since they have been supplied by Rockstar’s management) mask much more extreme exploitation. Firstly, any day (but not week) taken off counts in these averages, and thus brings them down. Thus the average hours worked in a normal week, without a day off, is higher.

Also, these averages include all employees, not just those working on making this game. One might assume that secretaries, cleaners, and caterers work fewer hours. So the developers working on Red Dead Redemption 2 were obviously working far higher hours.

This is backed up by the statistics for game testers at Rockstar’s studio in Lincoln. These workers have been testing the game before release in order to iron out bugs; their work is therefore tied entirely to this game. They are also seen as the most dispensable and low-skilled of the industry’s workforce. The data shows that:

“The studio had asked day-time testers at Lincoln to work 52.5 hours a week between October 9, 2017 and August 6, 2018. This was framed to employees as a company request to work two-and-a-half extra hours on three of every five weekdays, and to work one 7.5-hour weekend day every four weekends. Night-shift testers were asked to work 45 hours for some of that stretch and then 52.5. Workload requests from Rockstar management increased to 57.5 hours per week in August and September of this year, according to Kolbe’s data.” (Kotaku.com, 19/10/18)

The levels of exploitation in this un-unionised industry are revealed by the fact that these comments from Rockstar are meant as their defence. For them, a working week just shy of 60 hours is something to celebrate as proof that the company is not exploitative!

Proletarianisation

A point that the employers emphasised is that none of this overtime – which is not paid at all for many of their workers who are not on an hourly wage – is mandatory. Interviews conducted with Rockstar employees by the websites Kotaku.com and Eurogamer.net mostly confirm that the overtime is technically not mandatory.

A point that the employers emphasised is that none of this overtime – which is not paid at all for many of their workers who are not on an hourly wage – is mandatory. Interviews conducted with Rockstar employees by the websites Kotaku.com and Eurogamer.net mostly confirm that the overtime is technically not mandatory.

But anyone who understands the precarious conditions of work in the modern world know that this is a fiction. If workers are unorganised it is easy for bosses to exercise the most draconian regime and to enforce whatever they like. And this is an industry in which trade unions are completely unknown.

As in other industries, casualised, temporary contracts are normal. We spoke to Marijam Didžgalvytė from the brand new campaign for unionisation of the industry: Game Workers Unite. She says that over the past few years, the games industry has become far more proletarianised and insecure.

“Casualisation, zero hours contracts, freelancing, outsourcing, have all become far more prominent. They are the norm now. Workers’ rights are constantly being chipped away. They use what is called ‘speculative labour’, meaning they get workers to compete with each other to come up with huge numbers of designs, which is a vast amount of work. The employer then just takes what they like and all the other work is discarded. The conditions are worsening; it is more proletarianised. Stable full-time jobs are going, as is job security.”

At Rockstar, this means that “you go from contract to contract,” one former developer explained.

“That’s either six months or a year. And at any one of those intervals, you can be let go. If you don’t do the overtime, you will be let go. If you don’t work enough overtime, you will be let go. No one I talked to ever exercised the option to decline overtime.” (Venturebeat.com, 25/10/18)

Kotaku.com reporters were told the same.

“This overtime is NOT optional, it is expected of us. If we are not able to work overtime on a certain day without a good reason, you have to make it up on another day. This usually means that if you want a full weekend off that you will have to work a double weekend to make up for it.” (Kotaku.com, 19/10/18)

This hidden pressure, this constant fear that you could be replaced at any moment by another worker, plagues the industry. These are classical conditions of proletarian work and they are at least as strong in this industry as any other.

The fear of losing your job is so great that even legal protections are irrelevant. According to Eurogamer.net: “For night shifts, UK employment laws state a person can only work eight out of every 24 hours, but Rockstar employees sign agreements to waive this condition”. (Eurogamer.net, 26/10/18) Unorganised workers are defenceless even when legally protected. They will waive their own rights in return for a wage.

Rockstar consciously uses this fear to get the most out of their workers, keeping them at the company long past their breaking point.

“One common fear at Rockstar is that if you leave during a game’s production, your name won’t be in the credits, no matter how much work you put in. Several former Rockstar employees lamented this fact, and Rockstar confirmed it when I asked. ‘That has been a consistent policy because we have always felt that we want the team to get to the finish line,’ said Jennifer Kolbe. ‘And so a very long time ago, we decided that if you didn’t actually finish the game, then you wouldn’t be in the credits.’” (Kotaku.com, 23/10/18)

The crunch

It goes without saying that these conditions are disastrous for the mental and physical health of game workers. Eurogamer quotes a Rockstar employee saying:

It goes without saying that these conditions are disastrous for the mental and physical health of game workers. Eurogamer quotes a Rockstar employee saying:

“I am tired. I don’t have time for myself, or to see those I care about. I don’t remember the last time I went on a date with my girlfriend. My family live 30 minutes away and I don’t remember the last time I saw them in person. There are friends I used to see on a weekly basis that I am now lucky to see every few months. There are friends that I used to see every few months that I haven’t seen for years.”

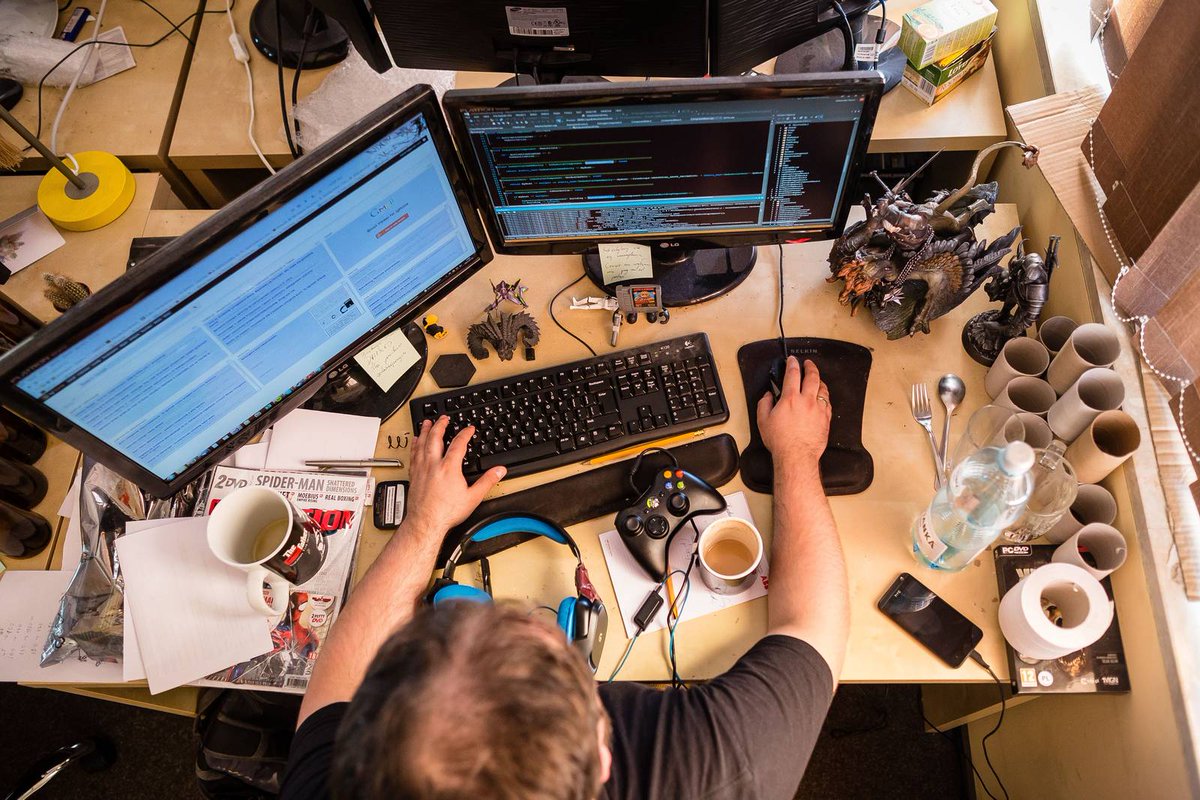

Many employees mentioned the prevalence of people sleeping in their offices, in sleeping bags they keep under their desks.

“They would work until two or three in the morning, then unroll their sleeping bag, go to sleep under the desk, then get up at six or seven and start working again. It was usually two nights because it would become unbearable. And then you’d do a normal day – finishing at eight o’clock.” (Eurogamer.net, 26/10/18)

Across all these articles, time and time again different workers reported suffering from depression and feeling suicidal as a result of sustained periods working in this way.

The routine of sleeping under desks brings to mind the stories of Sports Direct, JD Sports and Amazon warehouses, in which workers carried bottles for urinating into, so as not to lose time in toilet breaks. One worker even gave birth in the toilet for fear of losing a shift.

There is nothing unique about Rockstar games. It has simply become a lightning rod due to its fame. There are many similar stories from many other developers. Do a google search for pretty much any well-known game developer and the word ‘crunch’ (the industry name for periods of intense, excessive work), and you will find reports of extraordinary working hours. For example, Amy Hennig talks of workers at Naughty Dog developers working seven days a week for years (gamesindustry.biz, 6/10/16). Marijam, meanwhile, told us that:

“‘Crunch’ is not down to managerial failure. Maybe it was in the past. Now it’s written into the schedule of game development. It’s not an accident at all, and it’s completely pervasive. It’s true that some game workers do have the passion to do long hours on a game they love – but they need to be paid overtime rates for this, and it needs to be a genuine choice so that those with families etc. don’t have to. Only workers’ solidarity and unity can overcome this, because otherwise bosses can divide us.”

In 2012, a former Codemasters employee detailed that after working over 400 hours unpaid overtime in eight months, he and others were mistakenly overpaid after they were laid off. Codemasters then threatened to file bankruptcy proceedings on behalf of these workers, should they not pay back what they were mistakenly overpaid!

Earlier this year, Telltale Games, makers of the popular Walking Dead series, called the entire workforce in for a “meeting where the CEO Pete Hawley announced that 90 per cent of staff were being let go and had 30 minutes to leave the building, with no severance and healthcare coverage for only nine more days,” (gamesindustry.biz, 18/10/18) after investors suddenly pulled out.

Unionisation

This appalling, extreme exploitation is an industry-wide problem. It is especially acute in the video games industry because this is an industry that has never been unionised. Like so many other skilled, degree-required professions that have rapidly grown – in an epoch where capitalism has reached a dead end and entered a protracted crisis – it has been thoroughly proletarianised.

This appalling, extreme exploitation is an industry-wide problem. It is especially acute in the video games industry because this is an industry that has never been unionised. Like so many other skilled, degree-required professions that have rapidly grown – in an epoch where capitalism has reached a dead end and entered a protracted crisis – it has been thoroughly proletarianised.

The idea of unionising the industry finds much greater support amongst young games workers. This reflects the worse conditions they are subject to. This also reflects a generational change in consciousness that we find everywhere. The wider precarious workers movement is also an expression of this. And it lies behind the rise of the Corbyn movement too.

Workers in industries previously thought un-unionisable, such as fast-food workers, are organising rapidly, taking strike action, and scoring victories. Game Workers Unite are part of this burgeoning movement and are blazing a trail that could catch on very quickly.

Marijam agrees that there is a generational shift in the class struggle and that this shift is affecting the games industry. The culture of gaming, both amongst consumers and workers, has seemed (up until recently) right-wing and ‘libertarian’. But she says that this is changing in a big way.

“There is momentum in the class struggle, at least amongst young people. Our militant organising, which we are only just starting to do, can and must change gaming culture. Leftists must get involved in gaming culture – it’s huge. Only three or four years ago I would hide my games from my housemates, who were left-wing climate activists, because I was embarrassed and thought they would see games as nerdy and right-wing. We leftists mustn’t be snobs and ignore gaming. It’s a huge community; a young community. It’s now bigger than the entire film industry. We must say to game workers who’ve been influenced by the libertarians and alt-righters that it’s not through racism and sexism that one’s material conditions improve – it’s through class-based organising.”

According to Marijam the campaign is only a few months old, but is finding an echo and spreading rapidly.

“It was born very quickly, in March of 2018, at a game developers conference in San Francisco. There was a panel session hosted by the International Game Developers Association that was anti-union. The hashtag #gameworkersunite started trending, and led to a bunch of game developers and activists bursting into the room and taking the meeting over! We now have chapters in US, Belgium, UK, Australia, Brazil, Germany and Canada. In France, one year ago, others formed an official trade union (the first ever in the games industry), the STJV.

“The way our campaign has exploded – and it’s not even officially started yet – shows the consciousness amongst game workers has changed suddenly. The first time we have a protest outside a big company’s offices, it will be huge and will resonate with workers massively. We are gaining so much support. For example Jim Sterling, one of the biggest video game Youtubers, backs us. His six most popular videos are all about trade unions and labour issues in the games industry. That makes me very optimistic. We are part of a movement that is instilling solidarity and class consciousness in a younger generation.”

We asked Marijam what the next steps are and what game workers can do. She said the union will have its official launch very soon. Workers wanting to get unionised need to start by bringing the idea up with their fellow workers.

“Organise a social, chat to them about the conditions. We will be a workers’ led union. If you go to our twitter (@GWU_UK) there’s a link to a google form. If you fill it in that will take you into our chat so that you can join and help us.”

Broken system

This change in consciousness Marijam talks about is behind the sudden flood of articles in mainstream games websites about the terrible working conditions.

This change in consciousness Marijam talks about is behind the sudden flood of articles in mainstream games websites about the terrible working conditions.

In almost all of the articles, however, a naive, moralistic attitude predominates. They ask: Why should video games have to be made this way? Don’t Rockstar make enough profits? Surely they can employ more people, treat them all better, give them fewer hours and develop games differently?

But the bosses of these giant corporations are not guided by morality. These companies are capitalist, and exist in the context of capitalism: a system driven by profit; a system that is rapidly casualising work, paying less, and pushing down conditions.

There is a steady stream of workers desperate for what they hope is a good job. If they can be super-exploited and treated terribly, so they will be. Until, that is, the workers unite and fight.

This struggle is not unique to the games industry. It is the same across all industries and across the world. It is the struggle against capitalism and for socialism. And games workers are joining an ever-growing band on this quest.