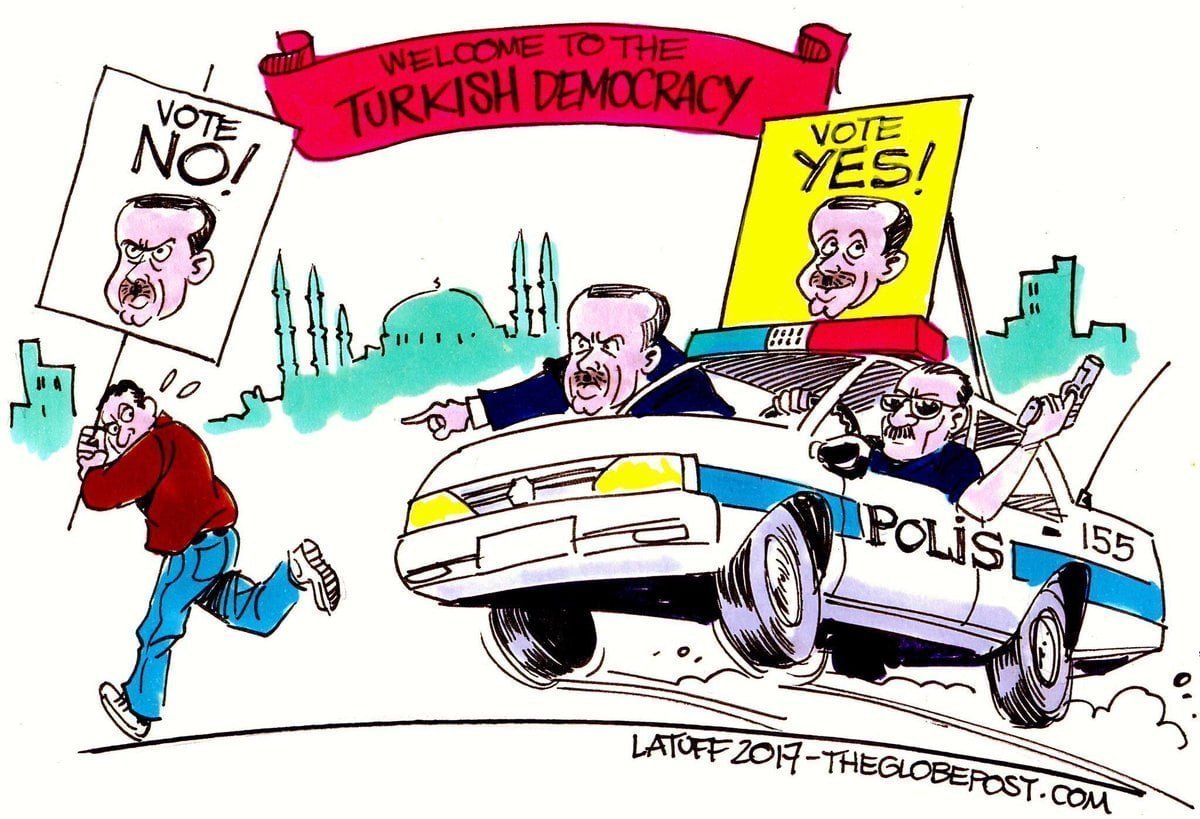

Recep Tayyib Erdogan officially won the YES vote in Turkey’s referendum to grant him, as president, sweeping and unchecked powers. But while the referendum was staged to give the impression of a strong regime with solid backing – a democratic vote for dictatorship, as some had called it – it has, in fact, revealed the exact opposite.

Recep Tayyib Erdogan officially won the YES vote in Turkey’s referendum. But what was the character of his victory and what does it mean?

According to the official results, some 51.3 percent of the 48 million voters voted to accept the new constitution which gives sweeping and more or less unchecked powers to the president. Turnout, officially at 84 percent, was very high and the mood in the whole country extremely polarised.

What was at stake, was not merely a change in the system of governance, but a vote on President Erdogan and the AKP regime itself. It reveals a society which is divided into two diametrically opposed camps. Acknowledging the result, Erdogan immediately went on the offensive saying, “We’ve got a lot to do, we are on this path but it’s time to change gear and go faster… We are carrying out the most important reform in the history of our nation.” Later on in the evening he called for the reintroduction of the death penalty. The state of emergency was also immediately extended

But while the referendum was staged to give the impression of a strong regime with solid backing – a democratic vote for dictatorship as some had called it – it revealed the exact opposite.

A democratic vote?

There was nothing democratic about the vote. As we have reported before, the whole preceding period had seen the complete mobilisation of the state and the media to secure the YES vote. Both private and state owned media focussed almost solely on promoting the YES campaign, giving little or no space to the NO campaign. The campaign reached such ridiculous levels, producing a kind of self-imposed ban on the word ‘no’ in the media, leading to anti-smoking leaflets being recalled and a movie called “NO” being removed from the air!

President Erdogan threateningly equated a NO vote with “siding with the coup-plotters”. Everyone can understand what this threat means. More than 120,000 people have been fired from their jobs and 40,000 arrested after being accused of being complicit in the failed coup attempt in July 2016. Thousands of councillors, MPs, officials and party organisers of the leftist, Kurdish based, HDP, which was campaigning for a NO, have been arrested on trumped up charges.

Not to mention the siege and open war on the whole South East of the country, which has led to the complete destruction of dozens of towns villages and neighbourhoods, leaving thousands dead and tens of thousands without a home. In the period of the referendum campaign these tactics of intimidation and terror were completely synced with the campaign of the HDP, and with curfews imposed on towns and villages where it had planned events. In the past week alone curfews were imposed on 14 villages in the Lice, Kocaköy and Hazro districts of Diyarbakir. The atmosphere of intimidation and terror was magnified on voting day, as hundreds of thousands of police and military personnel were posted on the streets to “maintain security”.

Finally, in an unprecedented act, the Supreme Election Board (YSK) suspended the requirement that the envelopes and the ballot papers be sealed before the start of the voting process. This is not only illegal, but it is quite probable that this was part of a plan to rig the vote. The last time such a step was taken, was in 2004. Back then the number of the unsealed ballot papers were 145. This time the figure was approximately 2-2.25 million (!).

Coupled with this there has been a stream of videos showing outright vote rigging throughout the country. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s International Referendum Observation Mission (OSCE IROM) also reported that access was denied or limited to several polling stations. At the same time, the state controlled Anadolu news agency seemed to be reporting some results before the official election board had even counted them. Especially in the rural Kurdish areas, there were many instances of results reported which were highly dubious and unlikely.

In Bitlis for instance, the YES vote won with 59.35 percent of the vote, but this is a wild swing from the 45.74 percent AKP/MHP received in the November parliamentary elections and even higher than the 52.06 percent Erdogan received in the presidential elections in 2014 when he was at the apex of his popularity amongst the Kurdish population. Considering the violent oppression of Kurds which he has been carrying out since then, the results this year seem fantastic. Similarly, in nearby Van the YES vote received 42.72 percent of the vote yesterday, much higher than the 20 percent the two parties received in the June 2015 general election and the approximately 30 percent they received in November 2015. The figures seem suspicious to put it mildly, and they back up the many accusations of vote rigging which have been voiced from these areas.

The opposition parties, CHP and HDP, have refused to accept the result and have called for the unsealed ballots not to be counted. The HDP English Twitter account claims that the party is estimating a 3-4 percent manipulation of the vote. Groups of people also took to the streets around the country to protest the vote. These protests continued today on a larger scale as awareness of the scale of irregularities became more apparent. It is beyond doubt that, had there been a “level” playing field, Erdogan would have most likely lost the vote.

Declining support

In spite of all the vote-rigging, terror, intimidation and vote manipulation, what is most surprising is the low level of votes in favour of the new constitution. The final breakdown of the vote will not be ready for another 10-11 days, but the picture which emerges from the vote reveals a serious dent in support for the regime.

Compared with the parliamentary elections in November 2015 when the combined votes of the AKP and the MHP (the two parties behind the YES campaign) stood at 61.4 percent, the YES vote yesterday declined by 10 percent, or by approximately 4.2 million votes.

In the Kurdish areas, where the state was trying its best, and probably succeeded to an extent, to keep voters at home, 9 out of 10 provinces which have had their Kurdish friendly governors removed and replaced with centrally appointed trustees, all voted NO.

Most importantly, almost all the major cities have gone against Erdogan. In Istanbul, where Erdogan’s political career took off after he became the mayor, the NO vote won with 51.41 percent despite the fact that the YES camp parties received 57.34 percent of the vote in the previous elections. In fact the YES camp received less votes (48.65 percent) than the AKP received in previous elections (48.75). In the working class area of Fatih, the YES camp won with 51.35, but this is still less than the 52.2 percent the AKP received in 2015, not to mention the 8.1 percent the MHP received. In Umraniye, also a working class area, the picture is the same: YES 55.2, but 55.5 for the AKP in 2015 and 9.3 percent for the MHP.

The same process can be seen in Ankara where the AKP/MHP received 63 percent of the vote in 2015, but where the NO vote won with 51.15 percent. In Izmir as well, the stronghold of the CHP, the AKP/MHP alliance saw a steep decline, as their combined vote went from 42.38 percent in 2015 to 31.2 yesterday.

The NO vote won all the most important urban areas, Diyarbakir, Adana, Antalya in the same manner. In Antalya, the YES received 18.8 percentage points less than the 2015 result and the NO vote got a sweeping 59.08 percent victory.

Meanwhile, what pushed the YES vote, apart from the very irregular figures from the South East, were to a large degree the rural areas. It is not by chance that the biggest percentage of YES votes came from non-industrial areas such as Bayburt, Rize, Aksaray, Gumushane and Erzurum. However even here the YES-alliance lost massively compared to the previous elections: Bayburt by 11.58 points, Rize by around 5.7 points, Aksaray by 14.22 points, Gumushane by 16.27 points and Erzurum by 15.23 points.

Most importantly there was a decline in support in the core strongholds of the AKP in the new “Anatolian Tiger” industrial cities. The AKP is the party of the Anatolian capitalist class. But its electoral success has, to a large degree, been tied to the young working class in these areas where average incomes, along with the local general growth, have increased 4-5-6 fold, since the party came to power. But the stagnating economy is bound to increase class tension in these areas and break the remnants of the paternalistic relations which have had a big impact on economic and political life. This referendum may just have given us the first glimpse of class divisions in the AKP heartlands.

Of course, Erdogan did manage to win in the Anatolian Tiger regions, but he also saw for the first time significant declines in support. In Gazienatep, the heartland of Turkish Jihadism and a bridgehead in Turkey’s intervention in Syria, the YES vote received 62.45 percent, 8.79 points less than the two parties gained in 2015. In the urban districts of Gaziantep the YES received around 61 percent of the vote while it was the rural areas which guaranteed the overall average.

In Konya the YES vote received 7.88 points less than the AKP alone gathered in 2015 (74.52 percent). Here the YES vote received 13.04 points less than the two YES parties gained in 2015. This vote, again, was carried by the urban districts of Konya, Meram, Karatay and Selcuklu, which all voted YES, but at a lower rate than even the AKP alone received in 2015.

In Kayseri the YES camp retreated 16.17 points compared to 2015. In Denizli, a key Anatolian Tiger, which started its economic growth before the others and therefore has a more mature working class, the NO vote won, wiping off around 15 percentage points from the result of the YES parties in 2015. As long as the economy was growing and there was no real political alternative, the working class in Anatolia swung behind the AKP. But as ties with village life drift further and further away in the memory of the workers, the real class antagonism between the workers and the bosses become more and more apparent. It is only natural that this class differentiation will also reflect itself in the political field. As the economic crisis in Turkey deepens, this process will become stronger and a violent class struggle will ensue in Anatolia. These elections reveal the first phases of this process.

The process of declining support for the YES parties is visible throughout the country. It is difficult to see where this support has been taken from, but it is likely to be a decline in support for both parties. Even if we presume that the result only reflects a decline in MHP support, it would still be a warning sign for Erdogan who has relied on right-nationalist support to stabilise his rule for the past two years. In any case, had the MHP not supported the referendum, a lot more vote rigging would have been necessary to carry the victory for Erdogan.

Lack of an alternative

It was clear that Erdogan would not spare any means to realise his dream of a modern day sultanate. Besides outright rigging, his main tactic was, on the one hand to rely on the legacy of a booming economy during his rule and nationalist anti-Kurdish hysteria and terror on the other. He was promising stability as opposed to the threat of instability. It is clear that this had an effect on a certain layer of the population, mainly in rural areas throughout the country. But this effect was negligible.

The main reason why Erdogan was not defeated, was that there was no credible opposition campaign. The HDP was massively handicapped by the extreme anti-Kurdish mood whipped up by the civil war, as well as a massive crackdown which effectively paralysed its whole organisation. At the same time the party has not managed to break out of its political isolation and counter the daily attacks in the media portraying it as a Kurdish-only terrorist organisation.

The Kurdish question has now become completely tied with Erdogan’s fate. Had it not been for the civil war against the Kurds and the resulting divisions in the working class along national lines, he could not have stayed in power. Unfortunately, the main opposition party, the CHP, only plays into Erdogan’s hands by adopting the same rhetoric and by supporting a string of anti-Kurdish laws. In fact, in their protest over the vote, not one word was mentioned about the war being waged against the Kurds, who make up a fifth of the population, nor the brutal crackdown on the HDP, the fourth party in parliament.

More than anything, the current CHP leadership has excelled in its impotence. While Erdogan was mobilising the whole power of the state apparatus for the referendum, the CHP leaders were trying their best to retain their statesman-like status. Anger with CHP leader Kemal Kiliçdaroglu has been mounting amongst CHP supporters who see that his actions as a “loyal opposition” to legitimise the Erdogan regime go against the Kemalist roots of the CHP. The CHP leaders are far more afraid of whipping up an uncontrollable mass movement on the streets than they are of the prospects of an Erdogan neo-Sultanate. Even Erdogan doesn’t take the CHP opposition seriously. To Kiliçdaroglu’s calls to declare the vote void, he coldly replied: “They shouldn’t try, it will be in vain. It’s too late now.”

A dictatorship?

Erdogan was publicly raising hopes of getting up to 60 percent support in the referendum, yet it is now clear that he barely scraped past 50 percent. This is not a sign of a strong vibrant regime. On the contrary, it reflects a weakening regime which is lashing out to survive. What the CHP leadership and the traditional Kemalist big bourgeoisie fear more than anything is not Erogan’s sweeping powers, but that by moving away from formal bourgeois democracy, he is also eliminating the “safety valves” of Turkish capitalism. The more bonapartist his rule becomes, the less of a chance will there be to ensure an “orderly” – non-revolutionary – transition once his support has become too low to maintain his regime.

Erdogan, initially came to power on a wave of popular support and anti-establishment mood in Turkey against the army as well as all the establishment parties. His popularity was sustained by the longest boom in Turkish history. Since 2013 however, when growth started wearing off, the Gezi park protests erupted and after Turkey began intervening in the Syrian civil war, he has gradually been losing support. While this referendum seems to be a victory for his regime, it only reveals the continuation of this process.

Erdogan has only avoided the many crises by creating new ones. The war in Syria, the war against the Kurds and the enormous bubbles in the credit and property markets, are all problems which will not go away. At the same time, while he has taken on the Kurdish movement and different factions within the state and the ruling class, he has not taken on the Turkish working class, a class which has grown massively over the past 20 years and which has not seen a major defeat since 1980. In order to establish a firm dictatorship Erdogan would first have to crush this class, but any attempt to do so would end up with his own downfall. In the meantime, with the lack of a political alternative, the regime will continue down the same path, growing weaker with every crisis.