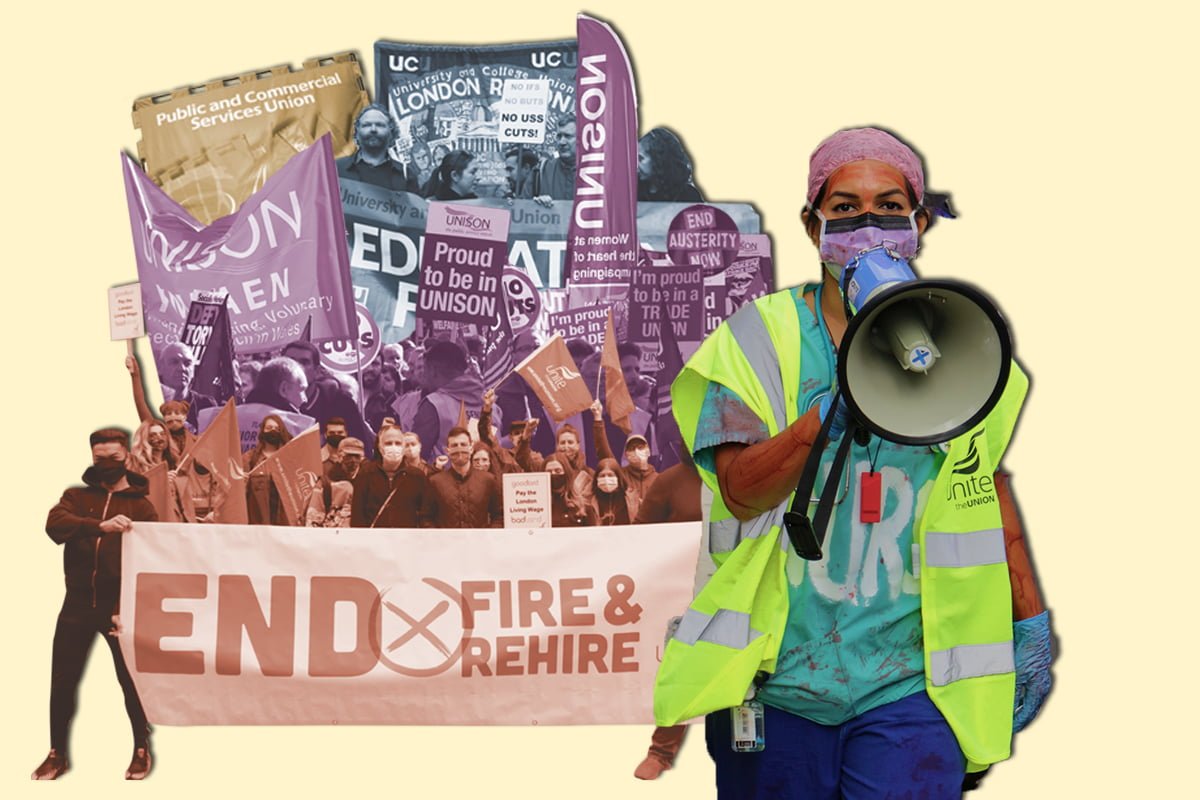

Britain’s winter of discontent has begun. With nurses, ambulance staff, and border guards all taking action, the country is set for its biggest month of strikes in decades. And the struggle is set to intensify, as the Tories threaten repression.

After many years – and even decades – of quiet on the industrial front, the working class in Britain is once again moving into action en masse. Every day seems to bring with it news about further groups and layers of workers joining the struggle. It is clear that a winter of discontent is well underway.

UK universities were shut down at the end of November. Long-running action by rail workers and posties is continuing in the run-up to Christmas. UK border staff have announced plans to strike at six airports from 23-26 December and 28-31 December. Up to 100,000 nurses are set to walk out on 15 and 20 December. And they will be followed by thousands of ambulance staff on 21 and 28 December.

Some of these strikes have occurred amongst workers with a tradition of militancy and organisation. The Rail, Maritime, and Transport (RMT) union and the Communication Workers’ Union (CWU), for example, both represent members in industries with high unionisation rates.

Other workers and unions – such as civil servants in the PCS, or teachers in the NEU – are seeing a return of national strike action after years of relative peace.

Many of the workers currently downing tools are entirely new to strike action, however, having been pushed into fighting by the capitalist crisis. From barristers to tech workers, more and more – and especially young workers – are looking to strike action as a way out.

Playing with fire

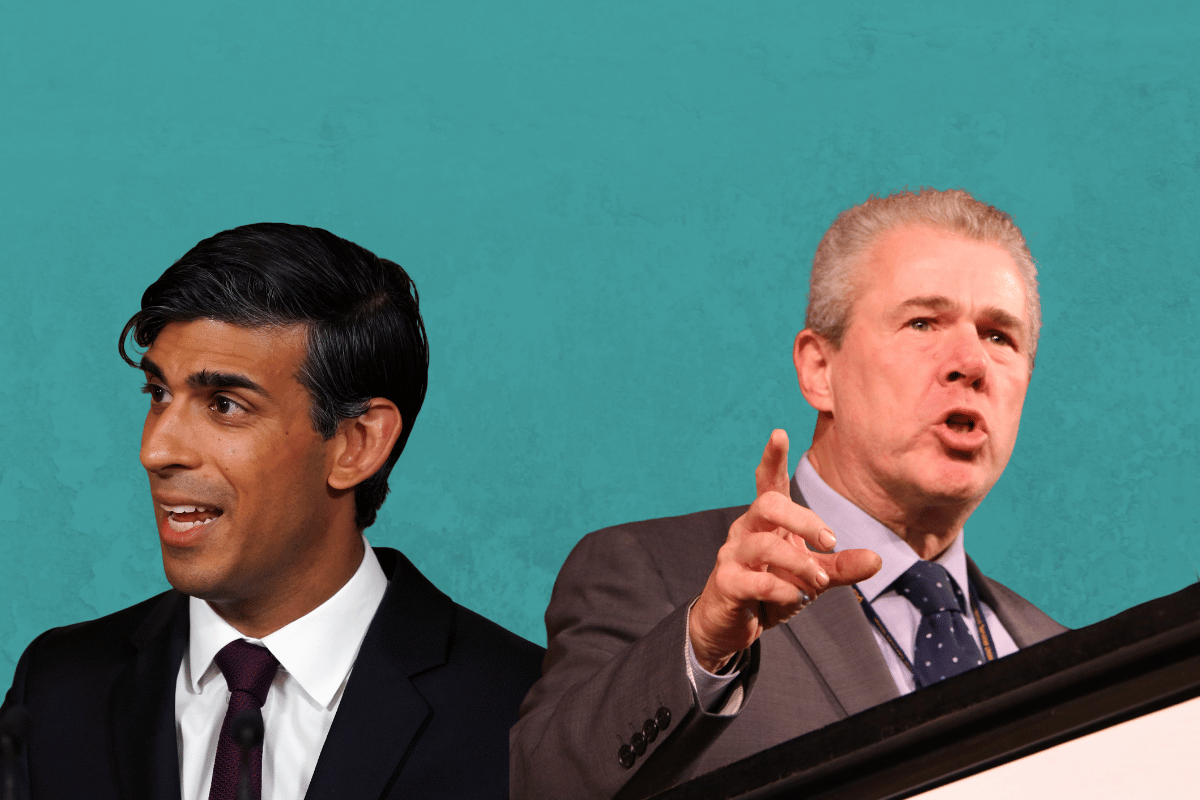

Alarmed by this growing wave of industrial militancy, Tory MPs are becoming more vocal in their demands for harder anti-union laws.

Alarmed by this growing wave of industrial militancy, Tory MPs are becoming more vocal in their demands for harder anti-union laws.

Speaking in Parliament yesterday, Rishi Sunak promised “new tough laws” to limit the impact of “unreasonable” strikes. This could mean legislation guaranteeing minimum service levels not only on transport, but for firefighters, healthcare, and ambulance services also.

In effect, this would mean stripping workers in these key sectors of their basic right to strike.

Those Tories looking to pursue this path are playing with fire. Moves by the government to tighten the country’s already-restrictive strike laws could end up provoking an even bigger backlash.

Already, union leaders such as Mick Lynch and Sharon Graham have correctly threatened to organise illegal mass action, if pushed by belligerent ministers. A full-frontal assault on workers’ rights could force a reply from the entire labour movement.

“We will not be intimidated by anti-trade union attacks,” stated Graham, the Unite general secretary, responding to Sunak’s statement at PMQs yesterday. “If they put more hurdles in our way, then we will jump over them.”

The Tories’ are clearly trying to intimidate workers against taking action; attempting to turn the wider public against those striking. But they are failing. Public support for industrial action is growing across the board. For almost every profession and sector, according to the latest YouGov polling, a majority of Britons support workers’ right to strike.

With workers everywhere facing the same attacks on pay, jobs, and conditions, militant action is breathing confidence throughout the entire working class.

? NEW: Britons are now more likely to support strike action in several professions according to YouGov tracker data.

Increased support for:

Nurses (+8)

Doctors (+6)

Teachers (+5)

Police (+6)

Firefighters (+7)(Changes since the question was last asked in June) pic.twitter.com/BoECpD1Ov3

— Taj Ali (@Taj_Ali1) December 3, 2022

Strike days

Within the trade union movement, meanwhile, right-wing leaders are clearly concerned that this strike surge could slip out of their control.

With motions for coordinated action passed at their recent congress, the TUC is now under pressure to deliver on this promise. As a result, there are rumours of a potential national day of action early next year, with all unions holding live strike ballots calling their members out on the same day.

Such a move would be an enormous step forward – encouraging new layers to join the fray, and emboldening workers to go further still. But it is precisely this prospect that gives right-wing union leaders sleepless nights.

For years, these leaders have justified inaction and foot-dragging by pointing out how – historically – strikes and union membership are at an all-time low. Instead, such conservative types call for ‘negotiation’ and ‘compromise’ with the Tories and bosses.

It is true that, compared to the high point of class struggle in the 1970s, the number of strike days lost in 2022 is still relatively small. But this fact in isolation tells us very little.

Data gathered by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for the period from 2002-22 paints an interesting picture. Ignoring obvious outliers (such as 2011, the year of the public sector pensions dispute), most months see between 80,000 and 250,000 working days lost to strike action, with a very small handful of years exceeding this level.

The difference compared to the most recent months recorded on the ONS graph is clear. The lowest point in these months is a respectable 86,000 days lost in July 2022; the highest, a notable 356,000 in August.

Estimates by the Financial Times, meanwhile, suggest that more than one million working days will be lost as a result of strike action taking place this month. And data gathered by strikemap.co.uk indicates that this winter will see the largest level of disruption due to industrial action since the summer of 1989.

In other words, a rising trend of strikes days lost is clearly emerging. And these numbers are only going to increase, with potential national action by teachers, junior doctors, and civil servants on the cards, alongside existing struggles by rail workers, posties, nurses, and lecturers.

Disputes

Of course, even this data does not tell the full story. If we also examine an ONS table about ongoing disputes (referred to as stoppages in progress), we can get a clearer idea of what is going on.

Of course, even this data does not tell the full story. If we also examine an ONS table about ongoing disputes (referred to as stoppages in progress), we can get a clearer idea of what is going on.

In the same period as looked at above (2002-2022), it is clear that the last four recorded months have seen a dramatic leap in the number of individual disputes currently active.

Compared to the last major peak (32 stoppages in progress in August 2006), the current strike wave saw no less than 75 simultaneous ongoing stoppages in August 2022 – a level of action that has largely remained solid in September, with 71 such stoppages recorded.

To take just one example, Unite alone has reported that the number of bus strikes fought by its union members across the country has shot up by 827%: from 11 strikes in 2019, to a whopping 102 since the election of Sharon Graham.

When both of these datasets are examined together, they show the scale of the militant mood emerging across the working class. The current strike movement is clearly wider than anything we have seen in decades. And there are clear signs that it is growing.

Reawakening

While this process is still in its early stages, there is good reason for enthusiasm. For many decades, the British working class was like a sleeping giant: potentially enormously powerful, but largely inactive, bar a few stirrings here and there.

Now, however, this giant is reawakening. When workers down tools in one region or workplace, taking on the employers, it is inspiring other workers to do the same thing. In these circumstances, confidence and militancy can be extremely contagious.

Across the public sector, this process is unfolding at a remarkable rate. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has already planned two days of national strike action for this month – the first in the union’s history.

Thousands of ambulance staff across three unions will join them the following week, as might junior doctors organised with the BMA early next year.

The FBU, representing firefighters, is currently balloting members. If this vote succeeds, it would lead to the first national firefighters’ strike since 2004.

In the civil service, PCS have announced plans to hit the government where it is most vulnerable, bringing out key departments over December in a campaign of targeted action.

This will include Border Force staff at six British airports, including Heathrow and Gatwick, who will be walking out over the festive holidays and in the run-up to New Year. As with striking ambulance staff and firefighters, government ministers have suggested that the military could be brought in as cover, in order to conduct passport and customs checks.

By January, further reinforcements will have arrived to bolster the growing army of striking workers, as the NEU, NASUWT, and National Association of Headteachers (NAHT) conclude their ballots.

This could lead to a potential schools strike of well over half a million education workers, joining members of the University and College Union (UCU) who are already shutting down UK campuses.

Coordination

In such a situation, the old lie that “our members don’t want to be called out on strike” rings increasingly hollow. Day by day, it becomes clearer to more workers that they cannot afford not to strike.

In such a situation, the old lie that “our members don’t want to be called out on strike” rings increasingly hollow. Day by day, it becomes clearer to more workers that they cannot afford not to strike.

This explains the upward trend in both strike days lost and ongoing disputes being recorded month-on-month. It also shows the way forward.

With workers already looking to each other’s battles for inspiration, and with the TUC recently adopting a resolution calling for greater coordination of the struggle, the time is ripe for the organisation of unified strike action to hit the government where it hurts.

Already, leaders of some unions – such as the RMT, CWU, UCU, PCS, and the teaching unions – have made concrete moves towards this. 1 October saw synchronised walkouts amongst workers in rail and mail. Similarly, last month’s university strikes were coordinated with those by Royal Mail workers.

This should now be broadened out to include the heavy battalions of the trade union movement, such as Unison, Unite, and GMB.

Furthermore, coordination at the top must be complemented with organisation on the ground.

This means establishing rank-and-file strike committees across industries and unions; and setting up councils of action in every town and city, in order to organise mass protests, rallies, and picket-line solidarity.

This would strengthen strikers’ actions from top to bottom, and draw together workers as one united force, bringing workplaces across society to a standstill.

Where next?

Of course, we do not possess a crystal ball. We cannot predict every twist and turn. Nevertheless the general path ahead is clear.

There have already been a number of notable victories on a local level, such as the inflation-busting pay rises won by dockers, bus drivers, and bin workers. This demonstrates that militancy pays.

On a national scale, however, neither the government nor any major employers have yet to budge. Instead, the Tories and their capitalist backers are stubbornly digging their heels in, terrified of giving in to workers’ demands and setting a precedent for others to follow.

The ongoing rail dispute is a perfect example. Going over the heads of the bosses and their representatives in the Rail Delivery Group, the government has insisted upon driver-only operation on the railways as a precondition for any talks – a demand that they know the RMT cannot accept. The Tories, in other words, are purposefully torpedoing any hope of a deal.

Their refusal to budge, however, is only intensifying Britain’s strike wave, making these struggles even more bitter and hard-fought.

Whatever the Tories decide regarding tougher anti-union laws, with the crisis of British capitalism deepening, and a further round of massive austerity to come, the stage is set for a severe sharpening of the class struggle.

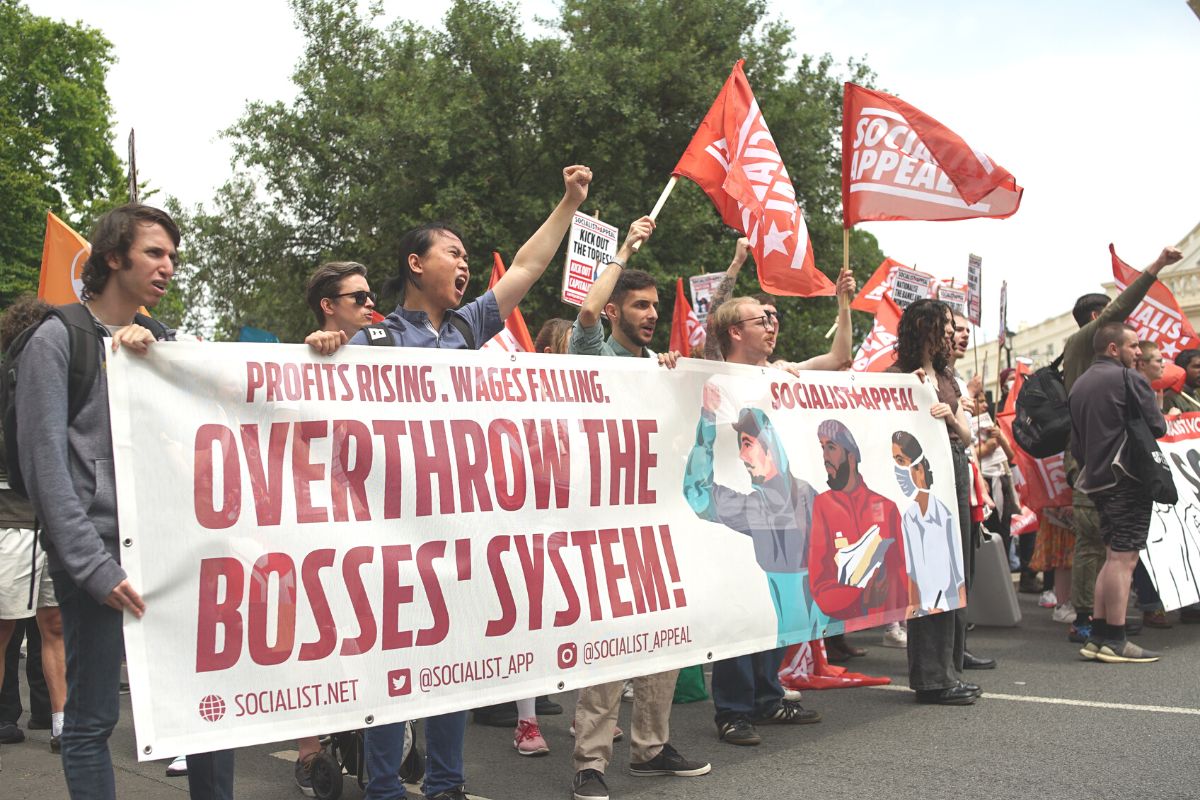

The trends outlined above will therefore continue to escalate. That, in turn, brings forth ever-more pressing needs for broad coordination of the movement – and for militant leadership at its head, armed with a clear socialist alternative.

Revolutionary leadership

The strikes we have seen so far have been impressive. But they are only the tip of the iceberg. The UK economy has already entered yet another long and damaging recession. And more cuts and attacks have been announced to make the working class pay for capitalism’s crises.

The strikes we have seen so far have been impressive. But they are only the tip of the iceberg. The UK economy has already entered yet another long and damaging recession. And more cuts and attacks have been announced to make the working class pay for capitalism’s crises.

As such, there is no sign that the industrial front will be any quieter in the year ahead. On the contrary, the potential for a public sector wide strike has never been greater. And on many picket lines and protests, calls for a general strike have even been raised – calls that will only grow louder if the Tories continue with their incendiary anti-union provocations.

To win, the movement’s leaders need to mobilise workers around a bold socialist programme, arguing for the nationalisation of the big banks and top monopolies, and the expropriation of the billionaires, in order to genuinely tackle the problems that the working class faces.

As the working class in Britain reawakens and rediscovers its old fighting traditions, the current strikewave is becoming a tsunami of class struggle – a rising tide that has the potential, with revolutionary leadership, to not only sweep the Tories from power, but to wash away the entire rotten capitalist system altogether.