For the past fortnight, the world has been treated to a macabre piece of theatre: an international, multi-million-dollar operation to save the lives of five crewmen of the Titan submersible, who – it now turns out – were almost certainly known to have died from the start.

Life is sacred. Who could object to any expense to save just a single soul? But if all life is indeed sacred, then some lives are clearly more sacred than others.

Five men – including British billionaire Hamish Harding, and a British-Pakistani multimillionaire and his son – voluntarily paid $250,000 each to descend in an untested death-trap, 3.5km below the Atlantic Ocean, to the site of the Titanic wreck.

Shortly into its descent, the sub simultaneously lost communication and tracking, exactly at the same time as the US Navy detected a loud bang.

It was obvious what had happened. The sub had catastrophically imploded. Its five passengers were certainly dead. We weren’t given this piece of information until debris was found four days later – information that certainly would have diminished this piece of media theatre.

The media would not be reconciled to the idea that such eminent persons should suffer such a cruel fate. They speculated day and night over sounds heard on the sea bed; over the oxygen capacity of the vessel; they counted down the hours; and they described the different stages of asphyxiation, hypothermia, and coma the sub’s occupants might be going through.

BBC reporters waxed lyrical about the “mournful fog” descending on Cape Cod from where they were reporting. Governments, authorities, and media outlets all wept for the rich adventurers and their families, and none would rest until the lost men were returned.

Governments, Navies, Coast Guards, and private companies formed a joint rescue mission. A Unified Command was formed involving the US Coast Guard, US Navy, and Canadian Coast Guard. Numerous maritime and sub-maritime experts were collected together. State-of-the-art technologies, including numerous sonar buoys, were deployed.

A huge fleet of ships and aircraft were dedicated to the mission: 3 Canadian Coast Guard vessels, 1 Canadian Navy defence vessel, 2 research vessels, 2 commercial vessels, 6 US military aircraft, 2 Canadian military aircraft, and numerous, high-tech Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs).

And four days later, a debris field was found precisely where it was expected: a few hundred metres from the submersible’s last known location.

This is how much a life is worth if you are one of the richest men in the world. Even when they are pretty much certain you are dead, no expense is spared.

And the lives of the poor?

The names and biographies of the Titan’s crew have been so widely discussed, they hardly need recalling. They are household names now: British billionaire Hamish Harding; the CEO of OceanGate, Stockton Rush; deep-sea explorer Paul-Henri Nargeolet; and heir to one of Pakistan’s biggest fortunes, Shahzada Dawood and his son Suleman Dawood.

Yet just one week before this sub went missing, 300 other Pakistani nationals went missing – locked in the hold of a fishing trawler, and drowned alongside hundreds of others in the Mediterranean.

It wasn’t a hunt for pleasure that drove these poor souls to board an unseaworthy vessel. They did so out of desperation.

Most of those from Pakistan came from rural Punjab or Azad Kashmir. Those who know it well describe Kashmir as a natural paradise: its white, snow-peaked mountains, its deep, lush, green valleys, its beautiful lakes. What causes a person to flee a paradise? Poverty and hunger.

Not one name or biographical detail has appeared in the international media. Weren’t their lives just as rich as those of a Hamish Harding or a Shahzada Dawood? Apparently not.

On 10 June, a vessel destined for Italy set off from Libya with 800 men, women and children on board. But at 11am on 13 June, whilst passing the Greek coast, pleas for help were sent out by the vessel.

And what was the response? What were their lives worth?

Did the Greek and Italian Coast Guards, joined by the Navies of Europe form a Unified Command to come to their aid? Did the media raise an outcry for these poor souls? Were a dozen aircraft and vessels scrambled?

For the first 11 hours after calling for help, not a thing was done.

Finally, at 10pm, a single Greek Coast Guard vessel attended the scene, at last. By that time, six of those on board the trawler had died of dehydration.

And what did they do when they arrived? Were they equipped with high-tech medical equipment, like that on board the Canadian Navy’s HMCS Glace Bay, which was deployed just in case the crew of the Titan were recovered?

No. The purpose of their presence was far more sinister. According to their own report – now proven to have been packed with lies – they “discreetly observed” the struggling vessel from afar.

If we believe the survivors’ testimony over the Greek Coast Guard’s – and we are certainly inclined to do so – it seems that the Greek Coast Guard intercepted the vessel, not to save lives, but to violently push it back into Italian waters, making it someone else’s problem.

But instead their actions likely capsized the vessel, sending 700 lives to a dark and watery grave, making it no one’s problem; or, rather, the mourning relatives’ problem.

The media noted the incident in the record of the day’s events, and issued a collective shrug of the shoulders.

All life is sacred. But not these lives.

These were mere “migrants”, and we “cannot tolerate more migrants” – as an MP from Greece’s ruling New Democracy party put it in the wake of the events.

These are an “invasion” to use the Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s rhetoric, and they are treated just like invaders. This includes the threat by the British government to use military naval vessels to repel them.

Every year, more than 2,000 lives are lost in the Mediterranean – 25,000 since 2014. That is 17 times the number of lives lost in the Titanic disaster 111 years ago, in less than a decade. Perhaps in decades to come their graves too will become a tourist attraction for wealthy pleasure seekers?

This is the difference between the worth of a rich man’s life and that of a poor man.

In anticipation of any objection that we are being unfair here to the Greek Coast Guard, and to the racist politicians of New Democracy, we would like to point out that their brother ruling classes in other countries regard rich lives as no less sacred, and poor lives as no less worthless. As proof we cite another recently forgotten tragedy.

Emanuele Macron, lost no time in personally ordering the 279-foot French research vessel, L’Atalante, equipped with a state-of-the-art Remotely Operated Vehicle capable of diving to 20,000 ft, to be dispatched all the way to the Atlantic when he heard of the Titan’s disappearance. These were the lengths he was capable of going to when his heart was stirred.

Yet when a distress call was received on a freezing November night in 2021 from an inflatable vessel in the English Channel, a mere 15 miles off the French coast, what did the French Coast Guard do? They ignored it.

Worse than that, they lied to the UK coastguard, telling them that they could not dispatch a rescue craft in the area because it was engaged in other “vital” tasks. It was not.

And finally, when a tanker vessel came across the distressed dinghy, they were told not to intervene because a French coastguard vessel was on its way. It was not.

27 lives were lost.

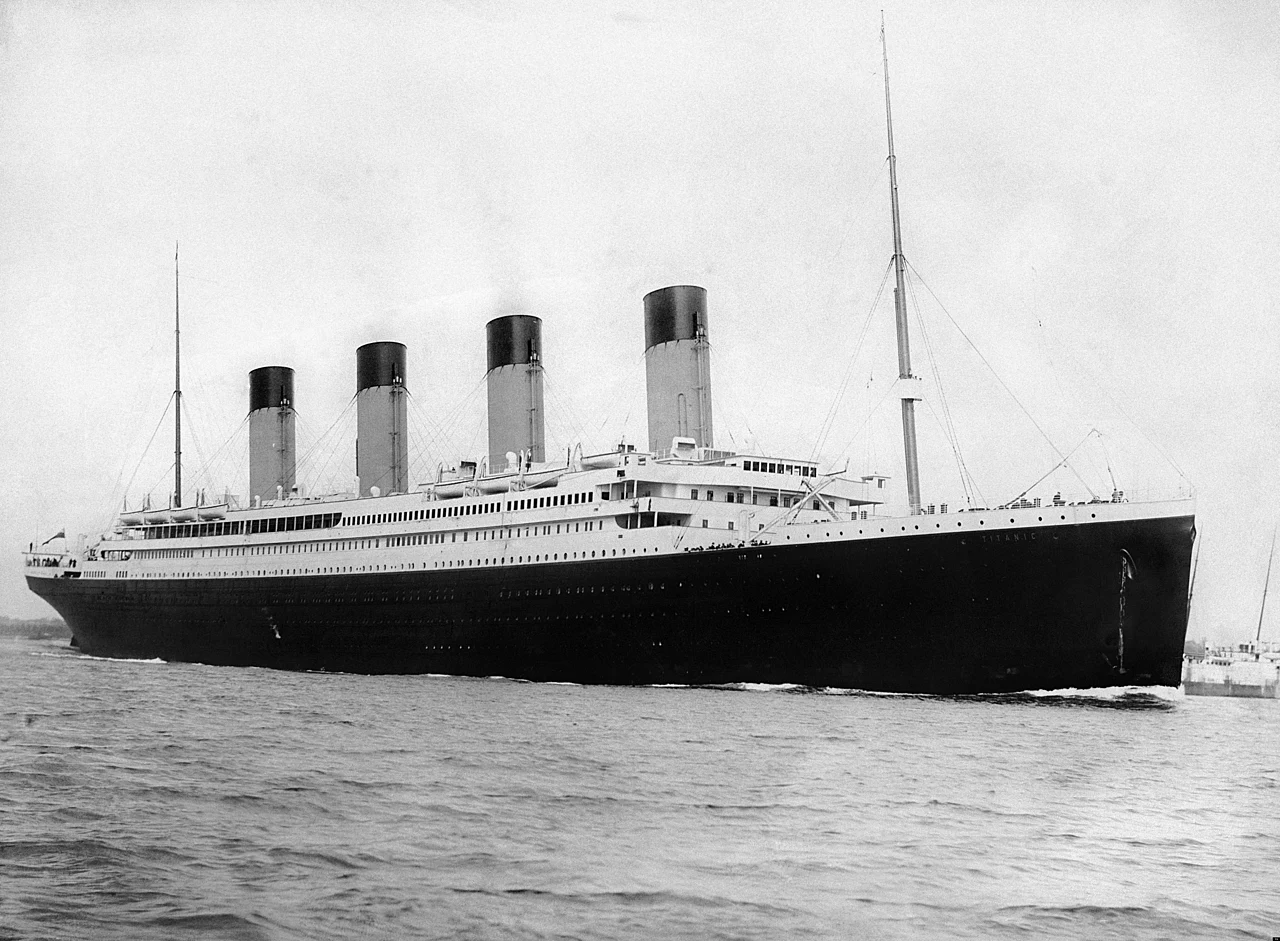

The Titanic

Out of respect for the dead, we do not wish to make much of the irony of the Titan’s implosion, which added five more to the mass grave of the 1,500 unfortunate passengers of the Titanic.

But it is worth saying a few words about the sinking of the Titanic, and the light it sheds on today’s world.

The Titan’s passengers were fairly warned that they were entering a death trap. The waiver for boarding the Titan included the word “death” three times on its first page.

Tragically, the five passengers became victims of OceanGate’s own cost-cutting, profit-seeking measures. The company had refused to submit the experimental carbon-fibre-titanium frame to an expensive testing and certification process. And indeed, the company’s own director of marine operations, David Lochridge, lost his job for writing a report in 2018 stressing that the craft was dangerous.

The Titanic’s passengers, on the contrary, were told they were stepping aboard an unsinkable vessel. The story of the Titanic concentrates within itself all the moral hypocrisy – all the same contrasts of concern for the rich and contempt for poor lives – that we see demonstrated in so many instances under capitalism today.

The story itself is well known. On 14 April 1912, the Titanic hit an iceberg on its maiden Atlantic voyage, sinking and taking 1,500 of its 2,200 passengers down with it.

The Titanic was equipped to cater to the tastes of its wealthiest passengers: it had an à la carte restaurant, a great lounge, and even a famous Grand Staircase.

But it also had its Third Class passengers, many of them Irish migrants. They were kept in special compartments, below decks, behind grilled gates to keep them from interacting with the First Class passengers. The former were regarded as carriers of disease.

When the vessel began to sink, those gates remained locked shut according to some witnesses – just as hundreds of Pakistani women and children were kept locked in the hold of that fishing trawler on that fateful journey from Libya to Italy two weeks ago.

39 percent of First Class passengers perished. 76 percent of Third Class passengers lost their lives, and 98 percent of Third Class male passengers died. In the words of one survivor, Mary Davis Wilburn: “The dead came up holding children in their arms. The poor people never had a chance.”

When the Third Class passengers were shoved by the owners of the Titanic into the ship’s hold, was the morality of the latter higher or lower than that of today’s human traffickers – traffickers now being blamed by European and Greek authorities, keen to divert attention from the blood on their own hands.

Another fact about the Titanic, known to anyone who has watched James Cameron’s film about the ship’s sinking, is that it lacked sufficient lifeboats to save its 2,200 passengers, thus leaving hundreds of the predominantly poorer passengers to drown.

What is less well-known is the reason. This was not so much a cost-cutting measure as a means to create a nice view for First Class passengers. You see, having sufficient lifeboats to save all passengers would have created an eyesore on the upper decks.

This echoes the use of dangerous, inflammable cladding by property developers to hide the ‘eyesore’ that the Grenfell tower block was deemed to be from the other – richer – residents of Kensington in London. This inflammable cladding led to 74 lives being lost in the tragic fire of 2017.

Horror without end

The two tragedies – in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean – are both horror stories. However, only in one of the two cases were the lives involved deemed worthy of saving by the great and the good.

These are the ‘values’ of our ruling class. They will go to the ends of the Earth, or the depths of the ocean, to save one of their own. But the working class, the poor, and above all migrants, are seen as a nuisance: raw material for exploitation, at best; and, at worst, as a mere surplus population, barely worthy of life.

The ‘democratic’, ‘civilised’ ruling classes of today share the same morality as their forebears of over a century ago, who allowed poor Irish migrants to sink to the bottom of the Atlantic.

Whereas Malthus two centuries ago lauded the social benefits of disease and hunger, today our politicians are on record, laughing and partying through the night, whilst their ‘herd immunity’ policies allowed COVID-19 to rip through working-class communities.

This point is not lost on millions of people. You can read it in social media posts about the Titan implosion; in workplace discussions; in bars and cafes. The lesson learned is, quite simply: live or die, they do not care about us.