Capitalism is entering into what looks set to be its deepest crisis ever. Although COVID-19 provided the trigger, a deep slump has been in the making for many years. With the stock market in turmoil, mass unemployment, and the perspective of a global depression, parallels are being drawn to the Great Depression of the 1930s – although even that may fall short as a parallel.

In October 1929, the Wall Street Crash brought a dramatic end to the so-called “roaring twenties”. The speculative bubble finally burst, as the whole system entered into crisis. Over the next few years, global production would collapse, and tens of millions would be made unemployed.

With class struggle on the rise, the New Deal was enacted in the USA in order to save the system from itself. Despite the measures taken, no lasting recovery would be achieved until the onset of the Second World War. In the meantime, the consciousness of a significant layer of the working class would be transformed.

Each crisis of capitalism has its own features. However there are many lessons to be learnt from studying the period of the Great Depression for revolutionaries today. We are once again entering into a stormy period of crisis, instability, and rising class struggle.

The Wall Street Crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 was one of the defining events of world history. Almost overnight, the lives of millions of people would be turned upside down by the invisible hand of the market. The relative stability of the previous decade (in the USA at least) had well and truly come to an end.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 was one of the defining events of world history. Almost overnight, the lives of millions of people would be turned upside down by the invisible hand of the market. The relative stability of the previous decade (in the USA at least) had well and truly come to an end.

The late 1920s saw an unprecedented frenzy of speculation on the American stock exchanges. By 1928, it was not unheard of for certain shares to rise in price by ten, fifteen, or even twenty per cent in one day. With the market on the rise, anyone with the means to invest wanted a piece of the action.

Although some warned about the dangers of a bubble, nobody wanted to get off the ride whilst the going was still good. Billions of dollars were loaned to investors in order to buy shares, often using the very same shares as collateral for the loans. So long as prices were rising, everyone was happy.

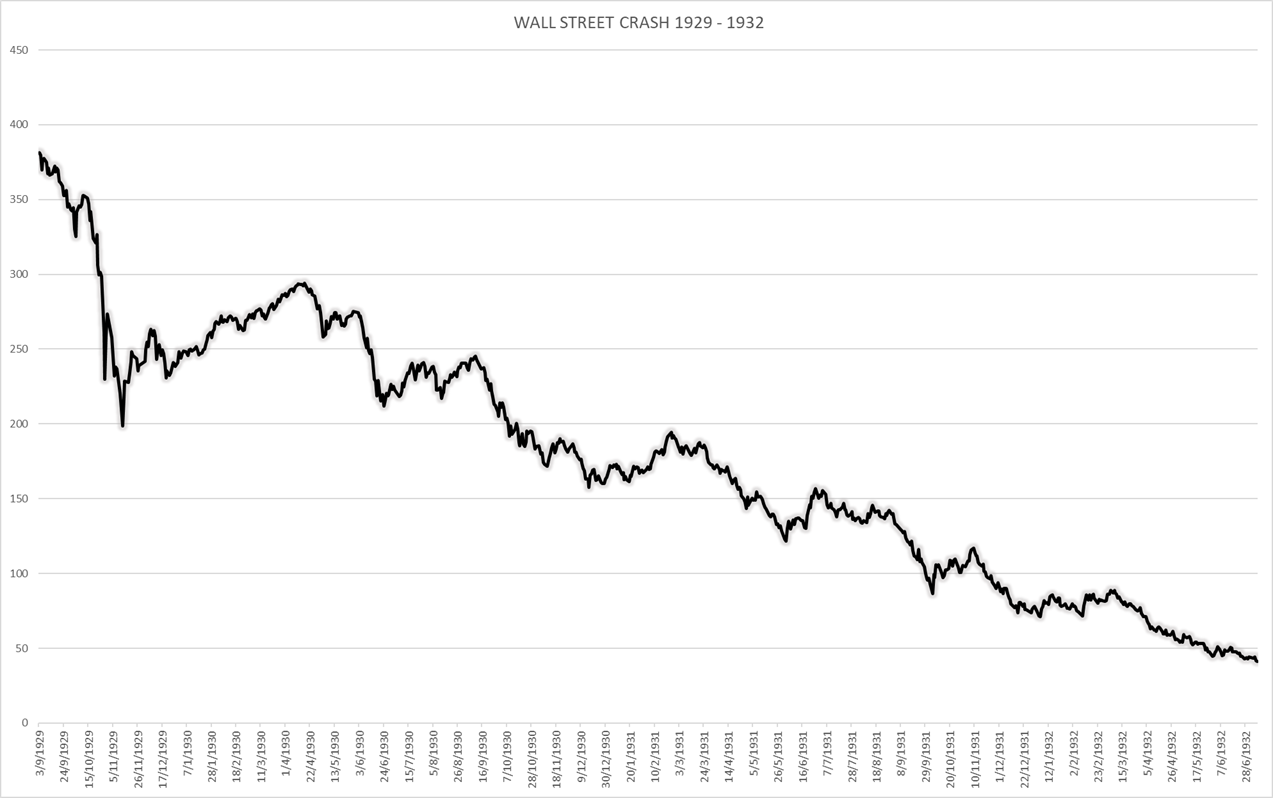

But every bubble must sooner or later burst. A general downward shift in prices began in September 1929, when the market peaked. By Friday 18 October, heavy losses were recorded on the New York stock exchange. The losses would continue to get worse over the next few days.

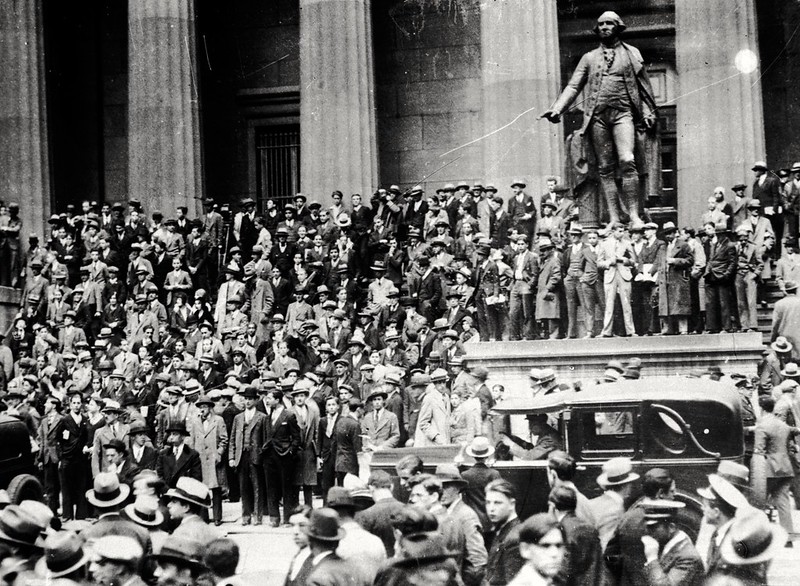

By the morning of “Black” Thursday, 24 October, the real panic set in. Investors scrambled to sell their shares at almost any price. Shares in some companies couldn’t be sold at all. Sensing catastrophe, the chairmen of the leading Wall Street banks rushed to declare their support for the market. This calmed things down, for a few days.

By Monday the collapse was back in full swing. No amount of bankers’ support could hold back the waterfall. In reality, the banks were rushing to unload their own holdings in order to save themselves.

The next day, Tuesday 29 October, saw the worst day of trading in the history of Wall St. In the first 30 minutes of trading, 33 million shares were sold. The Dow Jones industrial index declined by 30 points, wiping out all of the gains of the past year. In the space of two days, the index fell by 23 per cent. The bubble had well and truly burst.

The slump continued until 13 November, when the index closed at 198 – nearly 50 per cent below its September high. But then a temporary recovery occurred from January to March 1930. It seemed as if the worst was over. Herbert Hoover, the US president, stressed to investors that “the US economy is fundamentally sound”.

But the economy was far from sound. From April 1930, the stock market again tumbled. The index declined almost every week until it hit rock bottom in July 1932. By that point, the Dow Jones index was at 42, compared to its September 1929 peak of 381 – a loss of 89 per cent in under three years.

Share prices would not begin to rise again until early 1933. The recovery was so weak, that it would take until 1937 to climb back to the November low of 1929. But then in 1937 the economy again slumped, only to revive later due to the impact of the Second World War.

What caused the crash?

Irving Fisher, a leading economist, stated at the time that the crash was simply “a great accident”, caused by a “psychology of panic”. Although perhaps intended to reassure nervous investors, this was an explanation that explains nothing.

Irving Fisher, a leading economist, stated at the time that the crash was simply “a great accident”, caused by a “psychology of panic”. Although perhaps intended to reassure nervous investors, this was an explanation that explains nothing.

Other capitalist economists have pointed to a number of factors to try and explain the crash, and the depression that followed.

John Kenneth Galbraith, in his famous book The Great Crash 1929, argues that the crash occurred as a result of the inevitable bursting of a speculative bubble. But he then argues that the reason for the subsequent depression was due to a number of weaknesses in the economy, including (amongst others):

- Unhealthy corporate structures. Prior to the crash, large conglomerates and investment trusts discovered that they could “leverage” – i.e. multiply the effects of rising share prices – through complex company structures. When share prices dropped however, the effects were multiplied in reverse.

- The weak banking structure. Banking in the USA had yet to be centralised. Thousands of small banks dotted the country. With no federal insurance on deposits, the collapse of a bank would often spark a run on others, starting a chain reaction.

- The unequal distribution of income. In 1929, the richest five percent of the population took home approximately one third of the income. The economy was therefore reliant on high levels of luxury spending, or investment in capital goods. When this took a hit in the crash, a large chunk of effective demand in the economy was wiped out.

- The balance of trade. Since the First World War, the USA had become a creditor nation. When the crash occurred, many countries couldn’t pay their debts with gold. Neither could they increase exports to the USA, due to the imposition of tariffs. Therefore they had to reduce their own imports from the USA – resulting in shrinking the market for American commodities.

Whilst it is true that all of these factors had an effect in exacerbating the depth of the slump, none of them really explain why the crash occurred in the first place.

With or without these factors, crises are an inevitable feature of the economy under capitalism. The Wall Street Crash and the subsequent Great Depression were a product of all of the contradictions of capitalism that had built up during the preceding boom.

The “Roaring Twenties”

The American rich had never had it so good as in the boom of the 1920s – although conditions for most workers remained awful. The USA rapidly developed from the late 19th century to become the world’s leading industrial power after the First World War.

The American rich had never had it so good as in the boom of the 1920s – although conditions for most workers remained awful. The USA rapidly developed from the late 19th century to become the world’s leading industrial power after the First World War.

In 1900, the total wealth of the USA stood at $86 billion. By 1929 this had increased to $361 billion. This was the era of the rise of the first billionaires, such as Rockefeller and Carnegie, who consolidated monopoly positions over almost entire industries such as oil and steel.

Of the 300,000 companies in the USA, just 200 controlled nearly 50% of the total assets. As a result, in 1929 the richest 0.1% received the same total income as the poorest 43%.

From 1919 to 1929, the average rise in productivity in 59 industries was between 40 to 50%. With prices and wages remaining stable, this meant rapidly increasing profits for the rich and an explosion of inequality. During the boom of 1924 to 1929, industrial profits rose by 156 percent.

In the same period however, the price of industrial shares tripled. So although the economy was expanding, share prices were rising at a much faster rate than their earnings potential from dividends would imply.

In other words, there was a huge increase of fictitious capital. This was facilitated by the practice of buying shares “on the margin”, i.e. paying only for a small fraction of the price, with the rest being loaned.

With markets for commodities becoming saturated, but with rising share prices on Wall St, it became more profitable to speculate on the stock exchange than invest in actual production. With more and more capital seeking a profitable outlet, the rise in share prices took on a logic of its own. Fortunes could be made simply by riding the wave of the rising market.

Overproduction

As Marx explained, every boom under capitalism develops inevitably into crisis. At root, this is since production is organised for profit, and profit only. This profit comes from the surplus value produced by the working class, above that which it receives in the form of wages.

As Marx explained, every boom under capitalism develops inevitably into crisis. At root, this is since production is organised for profit, and profit only. This profit comes from the surplus value produced by the working class, above that which it receives in the form of wages.

But in order for the capitalists to realise this profit, they must first sell the commodities that the working class have produced.

However, taking the economy as a whole, if the working class produces all value, but is only paid a fraction of this value in the form of wages, who will actually be in a position to buy all these commodities produced? There’s a limit to how much the rich can consume. Shouldn’t the system therefore be in permanent crisis?

Capitalism can overcome this contradiction through a number of means. Firstly, by expanding the market. From the late nineteenth century, the USA did precisely this by directly or indirectly colonising large parts of Latin America, and other countries such as the Philippines. But with every imperialist power attempting the same thing, this expansion reaches its limits.

Secondly, not all commodities produced are to be bought and consumed by the working class. In order to compete with their rivals, capitalists must expand production. This requires investment in more machinery, raw materials, and infrastructure.

However, this does not fix the problem, but instead sets it up again on a higher level. Since to profitably set this expanded productive capacity to use, more commodities must be produced. These must themselves find a market.

In the late 1920s, capital investment was slowing down, as markets were increasingly saturated. Even during the peak of the boom, unused manufacturing capacity was up to 20%. So why invest in expanding production, if it was not profitable to use existing capacity?

Thirdly, credit is used to artificially expand the purchasing power of consumers. This was done in the 1920s, both internationally, as money was lent to other countries in order for them to buy American goods; and internally with the increasing use of instalment plans to purchase domestic goods.

But the use of credit has its limits. Eventually the borrower must pay back the loan – with interest. It is a means of temporarily expanding the market today, at the expense of that of the future.

All of these means can only delay the inevitable – a crisis of overproduction. This is a phenomenon that is unique to capitalism, i.e. a crisis grips the economy because too many things are produced; not too many things to satisfy people’s needs, but too many things to be sold profitably on the market.

By early 1929 there were signs that the system was reaching its limits. Figures for American car production, a key industry, illustrate this clearly. Production declined from 660,000 units in March 1929, to 440,000 in August. In September this dipped to 416,000, then to 319,000 by October. By November, after the stock market crash had begun, production slumped to 169,500, falling to 92,500 in December.

The Federal Reserve Index of industrial production showed a similar trend. Taking the level of 1923 to 1925 as 100, production reached a high of 126 in June 1929. This fell to 122 in September, 117 in October, 106 in November, and 99 in December. It was clear that profitable markets were drying up. The system was reaching its limits.

Nobody knows for sure what started the panic on Wall St. Some point to the collapse of Clarence Hatry’s financial empire in Britain as spooking investors on Wall St. Or the declaration of a regulatory investigation into Boston Edison, which stated that speculators had massively over inflated the value of its shares.

In any case, whatever the trigger, it was merely the accident that gave effect to the deeper necessity of the system to enter into crisis. All of the contradictions of the previous period had built up to breaking point.

Like a forest that has been dried out over years, all it takes is one small spark to set it ablaze. The crash on Wall St was simply the surface expression of a much deeper process of crisis that would engulf the entire system.

Depression

The crisis on Wall Street quickly rippled through the rest of the economy. The collapse of share prices meant that loans taken out to buy shares ‘on the margin’, were quickly called in. Credit, used previously to expand the boom, had now turned into its opposite. Instead, unpayable debts had to be repaid. A wave of defaults led to a crisis of the banking system.

With no federal insurance on bank deposits, a collapse of a bank meant losing your entire savings. Hence runs on banks became commonplace. Between 1929 and 1933, over 9,000 US banks collapsed.

Even before the crash, companies were cutting production as the market was saturated. Now, as both demand and credit dried up, so did investment. Millions of workers were made unemployed, as they could no longer be profitably exploited. This led to a vicious circle of a further collapse in demand, and a wave of corporate bankruptcies.

By spring of 1930, a major decline in production and investment set in, as profitability dried up. The Federal Reserve Board index of industrial production declined from 110 in 1929 to 57 in 1932 – almost a 50 per cent fall. Private construction fell further – from $7.5 billion in 1929 to $1.5 billion.

The crisis of overproduction is most graphically illustrated by the figures for capacity utilisation. According to Donald Streever, capacity utilisation in the USA in 1920 was at 94 percent, and averaged 84 percent in the twenties. By 1930 it had fallen to 66 percent, and reached a low of 42 percent in 1932. In July of that year, steel operations in the USA reached only 12 percent of capacity.

The only way for the ruling class to eliminate this ‘excess capacity’ was to close down factories and lower prices. This introduced deflation into the economy, since the unemployed could not afford to spend. Those that could were reluctant to spend today, when prices would be cheaper in the future. Deflation also meant that servicing debts became relatively more expensive, thus further dragging down the economy.

Social crisis

As with any crisis under capitalism, it was the working class and poor who were made to foot the bill. The ‘Great’ Depression meant a great attack on the already low living standards of workers and poor farmers. The crisis in the economy was quickly transformed into a social crisis of epic proportions.

As with any crisis under capitalism, it was the working class and poor who were made to foot the bill. The ‘Great’ Depression meant a great attack on the already low living standards of workers and poor farmers. The crisis in the economy was quickly transformed into a social crisis of epic proportions.

Unemployment skyrocketed. In 1929, a significant 1.5 million were already unemployed (about three percent of the workforce). This leapt to more than 12 million by 1932, and an estimated 13 million by March 1933 (no official records were kept). This was about 25 percent of all workers, and 37 percent if excluding farm-workers.

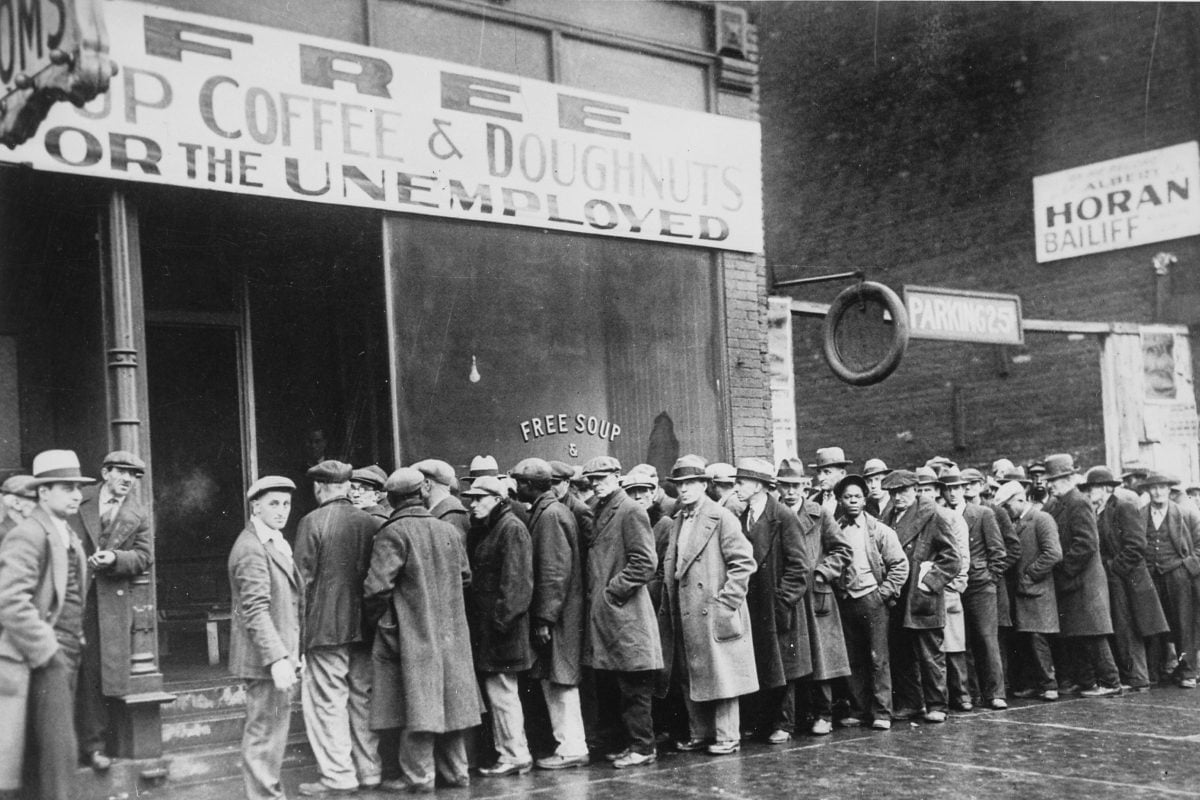

Overall, 34 million Americans belonged to families with no regular full-time wage earner. With no federal system of social security, workers were forced to turn to what limited charitable relief existed, or face starvation.

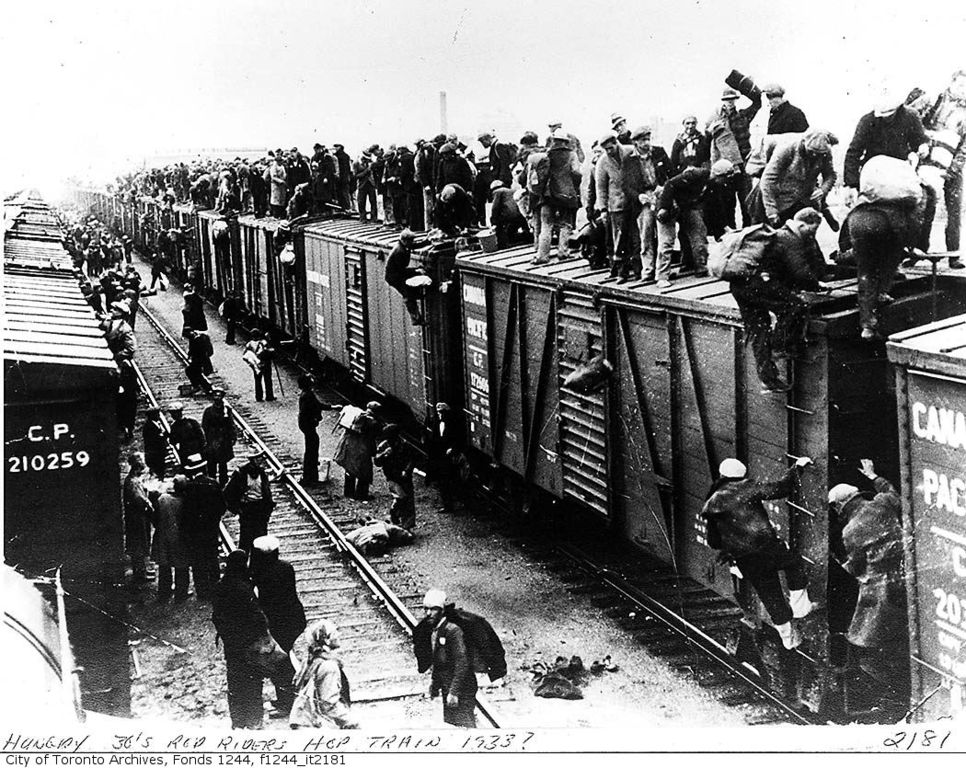

Unable to pay the rent, millions ended up homeless, travelling the country in search of work. Prospective homeowners were also caught in the crisis. An estimated 844,000 non-farm mortgages were foreclosed, out of a total of five million. Hundreds of thousands ended up in what became known as ‘Hoovervilles’ – shantytowns built out of scraps of cardboard, wood, and metal on derelict land.

In the context of these conditions, the bosses sought to restore profitability by driving down wages and increasing hours. Sweatshops appeared everywhere. Starvation wages were common, as was child labour. Many worked weeks of 60 to 70 hours.

With the shock of the crisis, the threat of destitution, and the lack of leadership from the trade unions, the bosses were largely successful in their attacks.

World crisis

With capitalism already operating as an integrated world system, the crisis in the USA quickly spread to other countries. In 1929, four major powers accounted for 70 per cent of world GDP: the USA, Britain, Germany, and France. Any disruption to world trade or capital flows would therefore have global repercussions.

When capitalism was booming, the USA was prepared to loan vast sums of money to help counties buy its goods. With the system in crisis and defaults on the rise, international creditors demanded payment in gold. This set off a chain of defaults all over the world.

All the major powers attempted to reduce their trade deficits by increasing their exports. In effect, they were trying to pass the burden of the crisis onto other countries. The USA tried to protect its domestic market by substantially raising tariffs in June 1930. This in turn had a devastating impact on the economies of Europe.

To facilitate exports, countries devalued their currencies by coming off the gold standard. Britain came off first in September 1931, followed by the USA in 1932. Despite attempts at international cooperation, a wave of competitive devaluations followed. The logic of competition between the different national ruling classes for a shrinking world market was too powerful to be overcome by international agreements.

The overall effect was a collapse of world trade, which helped turn the slump into a global depression. In 1929, American exports totalled $5.2 billion, whilst imports amounted to $4.3 billion. By 1932, American exports had fallen by 69 per cent to $1.6bn, whilst imports declined by 70 per cent to $1.3 billion. According to the League of Nations, world unemployment nearly tripled in this period to around 40 million workers.

Boiling point

By 1933, therefore, the world was in the midst of a severe depression. From the standpoint of the ruling class, conditions in the USA were getting critical.

By 1933, therefore, the world was in the midst of a severe depression. From the standpoint of the ruling class, conditions in the USA were getting critical.

Herbert Hoover, the president at the time of the crash, generally followed a laissez faire approach to handling the crisis. Taxes and interest rates were lowered, in order to encourage investment. But since avenues for profitable investment were so small (and in decline), these measures had little effect.

Hoover’s commitment to a balanced budget meant that government expenditure during this period was actually cut back. Since tax receipts had collapsed, government spending had to be cut. And unlike today, the banks were allowed to collapse, wiping out depositors savings in the process.

With no welfare system, the ground was being prepared for a social explosion. In the cities, the poor began to organise. Unemployed councils were established all over the country, typically led by communists. They organised people to resist evictions, as well as pressure the relief commission to ensure families obtained aid.

More alarmingly for the ruling class was the number of clashes with the police by the poor taking matters into their own hands. From 1931 onwards, hundreds, or sometimes thousands of unemployed workers would storm factories demanding work, or government buildings to demand food and shelter.

In the rural areas, where prices had fallen by more than 50%, conditions were becoming insurrectionary. The winter of 1932 saw the widespread phenomenon of large groups of armed farmers gathering to prevent foreclosures and evictions. Highways were picketed to prevent cheap produce being brought into towns, undercutting local farmers.

In January of 1933, Edward O’Neal, head of the Farm Bureau Federation, warned a Senate committee that “unless something is done for the American farmer, we will have revolution in the countryside within less than twelve months”.

This sentiment reflected the growing nervousness of a layer of the ruling class, which was increasingly losing confidence in its own ability to rule. With the presidential election approaching in November 1932, a layer of the capitalist class decided that a change of approach was necessary, in order to save the system from itself.

The irrationality of the system was becoming plain to see. Millions were hungry, whilst millions of tonnes of food were left to rot. People were reduced to wearing rags, whilst warehouses were full of clothes. Houses stood empty, whilst people slept on the streets.

Increasingly, workers began to organise self-help groups, to bypass the restrictions of the market. In the coal region of Pennsylvania for example, tens of thousands of unemployed miners dug small pits on company property, trucked bootleg coal to the cities, and sold it below the market price.

Rexford Tugwell, one of the architects of the New Deal, summed up the situation:

“I do not think it is too much to say that on March 4 [the day of the election] we were confronted with a choice between an orderly revolution – a peaceful and rapid departure from past concepts – and a violent and disorderly overthrow of the whole capitalist structure.”

The New Deal

Franklin D Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide victory in November 1932. After years of crisis, collapsing living standards, and destitution, millions were desperate for change.

Franklin D Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide victory in November 1932. After years of crisis, collapsing living standards, and destitution, millions were desperate for change.

The Roosevelt administration immediately set about a programme of sweeping reforms. These had the purpose of stabilising the economic system – at the time of the election the banking system had virtually collapsed – and pacifying the growing mood of rebellion across the country.

One of the first reforms was to provide emergency relief to the destitute. Agencies were set up to provide cash payments to those facing starvation. Money was allocated to buy up ‘surplus’ food from ruined farming areas, to be distributed in the cities. Similarly, ‘surplus’ clothing was bought up, to be handed to the poor. By doing so, it was hoped that the most desperate would no longer resort to rioting or stealing.

Most welfare however was to be provided through job creation schemes, or so-called ‘work relief’. Numerous organisations were established to employ millions of workers on construction and conservation projects – albeit, not on full wages. Notable among these were the Civil Works Administration (CWA), and the Public Works Administration (PWA).

The PWA provided billions of dollars to fund over 26,000 construction projects in all but three of the 3,071 counties of the USA. It was responsible for the construction of hundreds of thousands of miles of roads, tens of thousands of schools, hundreds of airports, as well as numerous bridges, dams, sewers, and tunnels. It is thought that 80 per cent of all public construction in the USA from 1933 to 1937 was funded by the PWA.

Industry

Other measures taken to stabilise capitalism included the passing of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in June 1933. As noted above, one of the effects of the depression had been a wholesale attack on the living standards of the working class. The bosses had attempted to maintain profitability by cutting wages and extending hours. This produced a race to the bottom, due to the effects of competition between the different companies.

Although this would have temporarily increased profitability, it also had the effect of reducing the effective demand in the market, by driving wages down to starvation levels. The NIRA attempted to reverse this by, amongst other things, fixing minimum wages, setting maximum hours, and abolishing child labour.

These were of course progressive measures from the standpoint of the working class. But we should be clear that they were measures taken by a capitalist government, ultimately in the interests of the capitalist class as a whole.

Along with many other aspects of the New Deal, they were a tacit admission that the market had failed, and that state intervention in the economy was necessary.

This can be seen in other aspects of the NIRA, which required the leading capitalists in each industry to come together to draft a so-called ‘code of fair competition’ which would regulate their sector.

In reality, this amounted to a suspension of previous ‘anti-trust’ laws, and allowed companies to act as cartels by fixing prices, or setting quotas on production. The aim was to boost the profitability of industry by effectively extending monopoly powers across a number of leading capitalists.

Agriculture

Farm prices had collapsed by over 50% between 1929 to 1932. Millions of farmers were facing financial ruin. The rural areas were seething with discontent. The Roosevelt administration therefore faced an urgent task to restore the profitability of agriculture. It did this in the only way that capitalism knows how – by enforcing artificial scarcity.

The previous Hoover administration’s policy of simply asking farmers not to produce had predictably failed. Therefore Roosevelt’s administration went one step further and actually paid farmers not to produce, through a system of farm subsidies. This was administered through the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA).

One problem for the AAA was that by March 1933, millions of acres of crops had already been planted, and millions of piglets had already been born. But with the rebellion in rural areas reaching fever pitch, action to raise prices could not wait. Hence farmers were paid to plough up 10 million acres of cotton, and kill six million young pigs.

At a time when people were starving, the policy of reducing agricultural production caused widespread moral indignation. Henry Wallace, the Secretary for Agriculture at the time, tried to explain that this was simply the logic of capitalism. He argued (falsely) that no one had been morally indignant when American industry had reduced its output between 1929 to 1933 by about $20 billion worth of goods! Here the irrationality of capitalism was plain for all to see.

Over the course of the New Deal, various other reforms were carried out in order to stabilise the system. Runs on banks were put to an end, through a federal insurance scheme on deposits. Debt relief was provided to mortgage holders, by means of government payments to the banks.

Not only did this prevent thousands of foreclosures, but it helped prop up the banks which were otherwise riddled with bad loans. And for the first time in US history, a nationwide system of unemployment benefits and old age pensions were introduced.

Effects

All of this meant a sharp break with the previous policies of laissez faire capitalism, where the state mustn’t intervene. Here was a tacit acknowledgement that if left to the mercy of the market, the resulting destitution would ultimately threaten the very viability of the capitalists’ rule. What the capitalists could not do as individuals, their state would step in to do for them.

All of this meant a sharp break with the previous policies of laissez faire capitalism, where the state mustn’t intervene. Here was a tacit acknowledgement that if left to the mercy of the market, the resulting destitution would ultimately threaten the very viability of the capitalists’ rule. What the capitalists could not do as individuals, their state would step in to do for them.

As summed up by Roosevelt himself in 1936:

“No one in the United States believes more firmly than I do in the system of private business, private property and private profit…It was this Administration which saved the system of private profit and free enterprise after it had been dragged to the brink of ruin.”

It is true that the policies of the New Deal did help alleviate the depression. After reaching rock bottom, American GDP rose by 34 per cent between 1933 to 1937. However, for a majority of the working class and poor in the USA, conditions went only from really bad, to just bad.

Even at its peak, the public works programme only employed a quarter of the total unemployed. Unemployment in the 1930s never fell below eight million. Minimum wages during this period were only just enough to cover necessities. Those on relief – either on work programmes or social security – fared even worse.

The idea – championed by John Maynard Keynes – that the government could lift capitalism out of crisis through state spending, seemed compelling. In the depths of the depression, a layer of the ruling class were desperate to try anything in order to save the system.

However, a major drawback with this approach was that the government itself didn’t have any money. It had to either raise it through taxes – therefore eating into the very demand it is trying to boost – or borrow it, increasing the deficit.

With the economy seemingly back on track by early 1937, Roosevelt came under enormous pressure from the capitalist class to return to a policy of balanced budgets. Having recently won the 1936 presidential election, Roosevelt then succumbed to this pressure in 1937, by scrapping relief programmes and raising taxes.

This policy succeeded in reducing the federal budget deficit from 5.1 per cent in 1936, to 0.1 per cent in 1938. However, the switching off of the life support to the economy resulted in a dramatic fall in economic activity.

The key question of a lack of profitable markets remained. Production did not reach the levels of 1929 until 1941, when unemployment was still 10 per cent.

Even Keynes himself commented that the New Deal had been unsuccessful in ending the depression:

“It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case — except in war conditions.”

Indeed it was precisely the Second World War that would finally bring the depression to an end: firstly due to the mopping up of unemployment through the military draft and war production; and secondly through the elimination of overproduction through the destruction of the productive forces on a global scale.

Class struggle

Human consciousness is profoundly conservative. We prefer to stick to what we know, what works. We establish routines. We fear change. This is the product of millions of years of evolution.

The Wall St Crash and the Great Depression meant a profound shock to the stability of millions of people’s lives. Initially, people were stunned by the crisis. There were hopes that it would be a temporary blip. So long as they kept their heads down, things would quickly return to ‘normal’.

As the crisis unfolded however, consciousness began to catch up with the reality of the situation. Panic turned to anger. People began to question why they were facing starvation, whilst at the same time food was allowed to rot in the fields. Or why they were being made homeless, when thousands of homes stood empty.

In the early years of the depression, this anger was not reflected in the level of industrial militancy. With unemployment so high, and destitution widespread, few workers wanted to rock the boat.

Trotsky summed up the situation in 1932 thus:

“The years of crisis have thrown and are throwing the international proletariat back for a whole historical period. Discontent, the wish to escape poverty, hate for the exploiters and their system, all these emotions which are now suppressed and driven inward by frightful unemployment and governmental repression, will force their way out with redoubled energy at the first real signs of an industrial revival.”

This is precisely what began to happen after the economy began to improve from 1933. With unemployment declining, and profits rising, workers increasingly went on the offensive to improve their position.

The turning point

In 1933, three times as many workers went on strike as in 1932. But the real turning point was 1934, which saw an explosion of industrial militancy. Previous to 1934, most struggles involved mainly the already organised striking to improve (or defend) their wages and hours. Now, the right to organise, and union recognition, were the main focus of strikes.

The confidence of workers to organise was in part boosted by a provision (section 7a) of the recently passed National Industrial Recovery Act. This gave workers “the right to organise and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing”.

Despite this right existing on paper, it was routinely ignored by the bosses. They enlisted the support of the police, the courts, and gangs of hired thugs, to violently smash strikes.

A series of large strikes developed in the spring of 1934. In Minneapolis – a key distribution city – truck drivers organised a solid strike to demand recognition of the Teamsters union. After four months, and several violent clashes – in one incident the police shot 67 strikers, killing two – the employers finally conceded.

In San Francisco, a strike of the Longshoremen (i.e. dockers) for union recognition turned into a general strike in July 1934. The employers gave into the union’s demands. Elsewhere, a strike of 325,000 textile workers in the American South quickly spread nationwide. By mid September, 421,000 textile workers had joined the strike – before Roosevelt intervened.

Transformation

Many of the strikes in 1934, particularly those in the mass production industries, ended in failure. In most part this was due to the conservatism of the leadership of the American Federation of Labour (AFL), and its policy of organising workers along craft lines.

Many of the strikes in 1934, particularly those in the mass production industries, ended in failure. In most part this was due to the conservatism of the leadership of the American Federation of Labour (AFL), and its policy of organising workers along craft lines.

For example, when rubber workers in Akron Ohio set up a union on a plant basis, the AFL leadership split up the workers into 19 separate craft locals. Such division would prove fatal.

However, pressure from below would end up transforming the union structures. Over the course of 1934 to 1935, hundreds of thousands of workers in mass production industries began to organise.

The AFL couldn’t ignore them. In 1935, it established a Committee for Industrial Organisation – to organise workers by industry, i.e. all workers in a single plant united together. Still facing resistance by a layer of the AFL leadership, the Committee split from the AFL in November 1935 to form the Congress for Industrial Organisation – the CIO.

The growth of the CIO was spectacular. Clearly a militant mood had built up in the American working class, which was desperate to find an expression. The AFL had provided little lead. What strikes it did organise (under pressure from below), were characterised by a desire of the leadership to compromise at any cost. In contrast, the CIO was characterised by militancy and energy. Importantly, it got results.

The rise in militancy was reflected in the changing tactics of striking workers. In the mid 1930s, striking workers began occupying their factories, in order to prevent the use of scabs. This tactic of the ‘sit-down strike’ quickly spread.

In 1936 there were 48 sit-down strikes. By 1937 this had risen to 477, including significant battles at General Motors and Chrysler plants – where the workers won union recognition

Within four years of its foundation, the CIO organised four million workers. These included breakthroughs in the auto industry, steel, rubber, and packing-houses. Even white-collar workers and agricultural workers rushed to join the union.

The general rise in militancy also had the effect of whipping the AFL into action. By 1939 it reported 4 million members – the highest level since its 1920 peak.

The situation was transformed. In the space of four years from 1933 to 1937, the total percentage of workers organised in the USA rose from 7.8 percent to 21.9 percent. This was an enormous step forward, and an important conquest for the working class.

But despite the huge potential that existed to harness this militancy into a political struggle for socialism, the union leaderships still lagged far behind.

Limits of the leadership

At the time of the passing of the NIRA, leading capitalists were furious at the inclusion of section 7a – giving workers the right to organise. Ernest T Weir, a capitalist in the steel industry, called it “one of the most vicious pieces of legislation ever proposed”.

However a more farsighted section of the capitalist class had a more sober opinion. Lloyd Garrison (later to become chairman of the National Labour Relations Board) said he was for the bill “as a safety measure, because I regard organised labour in this country as our chief bulwark against communism and other revolutionary movements”.

Garrison’s estimation of the trade union leadership proved to be correct. Despite the increasing militancy of the rank and file, union leaders – including those of the newly formed CIO – gave strict orders to their members not to participate in sit-down strikes.

John Lewis – president of the CIO – boasted to employers that “a CIO contract is adequate protection against sit-downs, lie-downs, or any other kind of strike”.

Since the union leaders had no perspective of socialism – i.e. the working class taking power and planning production for need – they ultimately played the role of dampening the militancy of the working class. Politically, they encouraged workers to support the capitalist Democratic Party, rather than lead the struggle to create a mass workers’ party.

During this period, the Trotskyists in America experienced significant growth. Numbering about 100 in 1929, their membership increased to about 1,000 by 1936. A year later they had about 2,000 members.

Although they would play an important role in struggles such as the Minneapolis Teamsters strike in 1934, ultimately they were too small to become a mass force in this period.

The impact on the class struggle was not confined to the USA. The ripples of the Great Depression would shake up the working class around the world.

In Britain, the Labour Party split over the question of implementing austerity. The rank and file in the Independent Labour Party would move far to the left.

The stormy years of the Spanish Revolution began in 1931, culminating in the civil war of 1936-39. France was rocked by a wave of sit-down strikes in 1936.

In Germany, the deep economic crisis – combined with the disastrous tactics of the Stalinist Communist Party – was a factor in the rise of Hitler to power.

Lessons

This period is rich in lessons for the labour movement today: both in terms of understanding the dynamics of capitalism in crisis; and, more importantly, on how the consciousness of the working class will be transformed.

This period is rich in lessons for the labour movement today: both in terms of understanding the dynamics of capitalism in crisis; and, more importantly, on how the consciousness of the working class will be transformed.

Today, the ruling class and their apologists are keen to emphasise that the current crisis is simply a result of COVID-19. But in the 1930s, a similar argument was put forward to blame the depression simply on the speculative excesses of Wall Street.

In reality, both COVID-19 and the speculation on Wall St were simply the events that triggered the system into crisis. At root, both crises were the result of all the contradictions that had built up to breaking point over the previous period.

Secondly, a depression is not a one-act drama; nor does it involve a permanent decline. There can be periods of stabilisation (as in early 1930), or even partial recoveries (as in 1933-37). In February and March 2020, stock markets around the world plummeted by about 35 percent, triggered by COVID-19 lockdowns.

Since then however, markets have rallied to recover much of their losses, in large part due to government rescue measures. This does not mean however that economies are recovering. In fact many bourgeois economists – including those of the Bank of England – are predicting the worst depression for over 300 years.

Significant is the high level of overproduction that has built up in the world economy over the previous decade. This will not be quickly overcome, especially since the class balance of forces worldwide rules out the possibility of a Third World War.

Thirdly, as evidenced by the New Deal, the ruling class will go to great lengths to save their system when they feel it necessary to do so. This can be seen today by the trillions spent by governments around the world to try and keep the system on life support. But these measures all have their limits.

The Keynesian deficit spending of the New Deal did not resolve the crisis of the Great Depression. And with government debts at sky-high levels as a result of the previous crisis of 2008, there is limited room today for any large-scale Keynesian projects anyway. More likely is the prospect of sovereign defaults, as government debts become unpayable. Massive austerity will be the order of the day.

Fourthly, such dramatic events will inevitably produce a profound shift in consciousness. In all crises, it is the working class and poor who are made to foot the bill. In the 1930s, it took several years between the onset of the crisis, and an explosion of industrial militancy.

Today, such a period is likely to be much shorter, given the massive anger that has built up in the working class over the past decade.

Finally, the inevitable rise in class struggle will result in the transformation of the mass organisations of the working class – the trade unions and political parties. It is likely that the existing union leadership will be either pushed far to the left, as a result of pressure from below, or replaced by a more militant layer.

Workers parties are likely to see the rapid crystallisation of a left wing at a certain stage, or enter into crisis. In countries where the traditional workers’ parties block the movement of the working class, new parties or formations can rapidly develop.

In these conditions, a much wider layer will be open to revolutionary ideas. The forces of Marxism can quickly develop from small groups, to become a factor in the situation. The ground is being prepared for the worldwide socialist revolution.

This article was originally posted on 7 August 2020.