We are living through the most turbulent period in the history of capitalism.

Poverty levels are growing everywhere. At the same time, a small minority, the ‘one percent’, is accumulating unprecedented quantities of wealth.

Working conditions are worsening as workers’ rights are being whittled away by the bosses. Wages are not keeping up with inflation, and benefits for the poor are being constantly cut. Housing prices are sky-rocketing, while rent is becoming unaffordable for many workers.

On top of all this, climate change is having catastrophic effects in many countries, from flooding to wildfires, with drought destroying the livelihoods of millions of people.

In these conditions, the imperialist powers are in conflict with each other over markets and spheres of influence, meddling in the affairs of every nation on the planet. This is producing instability and turmoil; wars and civil wars.

This is leading millions – if not billions – of people in all countries to ask themselves why this is happening, what are the causes, and what are the solutions.

Revolutionary communists have clear answers to these questions, and a programme to solve this crisis by tackling it at its roots.

View this post on Instagram

The Fourth International

What is this programme? And how do we connect it to the day-to-day struggles of the working class?

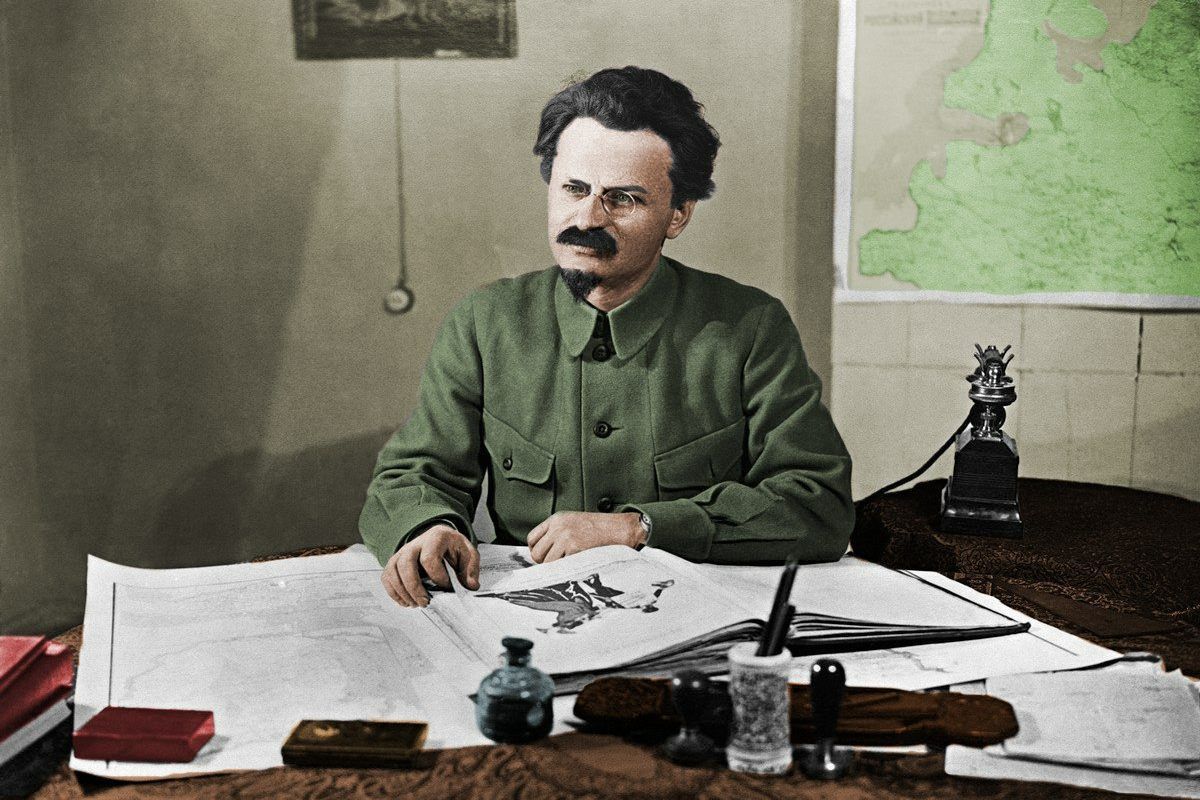

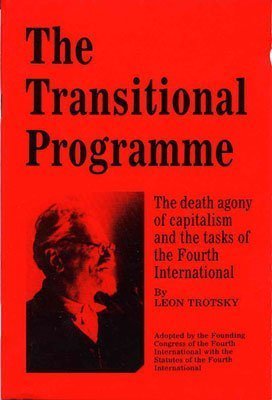

These questions are very skilfully dealt with by Leon Trotsky in The Transitional Programme, written in 1938 and adopted by the first congress of the newly formed Fourth International.

Along with Lenin, Trotsky led the Bolshevik Party and the working class to power in the October Revolution of 1917.

Both Lenin and Trotsky understood that it was not possible to build socialism in one country, especially in the extremely backward conditions of Russia at the time. That is why they consciously worked to spread the revolution internationally.

The old Second International had degenerated into a number of reformist parties, who had betrayed the working class by supporting their own ruling classes during the First World War.

Lenin and Trotsky worked assiduously for the establishment of the Third International. This became known as the Communist International, or ‘Comintern’. Its national sections, the various communist parties, were created to provide the working class with the necessary revolutionary leadership in each country.

Unfortunately, in one revolution after another, starting with the German Revolution of 1918, the communist parties proved to be either too weak to influence events, or theoretically unprepared for the great tasks that faced them.

These defeats led to the isolation of the Soviet Union. This, combined with Russia’s economic backwards, exacerbated by the devastation of the Russian Civil War, led to the gradual degeneration of the Soviet Republic. Power was usurped by a privileged bureaucracy, headed by Stalin.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, this process began to accelerate rapidly. In these conditions, Trotsky formed the Left Opposition, which advocated a return to the ideals of the October Revolution; to the genuine workers’ democracy of the early years after 1917.

A struggle ensued between the rising bureaucracy and the supporters of the Left Opposition. Trotsky was finally expelled from the Politburo in 1926 and exiled in 1928.

The Comintern, having failed to lead the revolutionary movement in one country after another, was transformed by degrees from an instrument of world revolution to an instrument of the foreign policy of the ruling bureaucracy of the Soviet Union.

A key turning point came with the victory of Hitler in 1933. The German Communist Party and the Comintern leadership failed to understand the nature of fascism. They mistakenly saw in the rise of the Nazis the preparation of conditions that would have allowed the Communists to take power, rather than the total crushing of the German working class, which was its true essence.

This allowed Hitler to come to power and liquidate one of the strongest workers’ movements in the world without firing a shot.

In any healthy international, such a catastrophic defeat would have provoked intense debate and internal struggle. And yet, throughout the Comintern, the false line of the bureaucracy was accepted with almost no resistance.

Trotsky thus proclaimed that the Comintern was dead as a truly revolutionary organisation, and declared that a Fourth International had to be built.

Crisis of leadership

What is remarkable about this document is that – as in the case of The Communist Manifesto – it seems even more relevant today than when it was written.

Its opening statement – “the world political situation as a whole is chiefly characterised by a historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat” – aptly describes the impasse facing the whole of the international workers’ movement in the present epoch.

The level of degeneracy of the labour and trade union leaders of today is unprecedented.

This has left the working class leaderless. And it also explains why right-wing, populist demagogues are able to gain traction and appear as if they are speaking for the workers. The responsibility for this lies on the shoulders of the so-called ‘leaders’ of the working class.

Everywhere, the reformist leadership of the working class has completely capitulated to the capitalist order. In Britain, the Labour leaders have become a mere appendage to the liberal bourgeois establishment, loyally serving the interests of the capitalist class.

The same is true of the social democratic leaders in Germany. Similarly, the ex-Stalinists in Italy dissolved the Communist Party into what has become the Democratic Party, whose leadership is thoroughly bourgeois in its thinking and programme.

In the United States, the trade union leaders are tied hand-and-foot to their own ruling class. The same situation can be seen in one country after another.

Socialism or barbarism

Trotsky’s text also seems to be describing the crisis facing capitalism today:

“Mankind’s productive forces stagnate. Already new inventions and improvements fail to raise the level of material wealth. Conjunctural crises under the conditions of the social crisis of the whole capitalist system inflict ever heavier deprivations and sufferings upon the masses. Growing unemployment, in its turn, deepens the financial crisis of the state and undermines the unstable monetary systems.”

And again:

“The bourgeoisie itself sees no way out. […] it now toboggans with closed eyes toward an economic and military catastrophe.”

At that time he warned that:

“Without a socialist revolution, in the next historical period, a catastrophe threatens the whole culture of mankind.”

That catastrophe came in the form of the Second World War, with its 55 million dead; with the horrors of the Holocaust, and the generalised destruction that afflicted many countries.

Today we are not facing a world war in the immediate period. But we have many local and regional wars, civil wars, and armed insurgencies, terrorist attacks, etc., afflicting many parts of the world.

We can say that the present crisis of world capitalism presents us once again with the prospect of either socialism or barbarism. The elements of barbarism are already present in the wars and civil wars; in the famines that regularly affect different parts of the world; in the growing poverty, and with it violence and crime.

We have also seen the potential for socialism in the mass class struggles and revolutions in many countries: from the Arab Spring of 2011, to the revolutionary upheavals in Sri Lanka (2023), Bangladesh (2024), and today in Nepal and Indonesia.

Need for a programme

The question of questions is: how can such mass movements be directed towards the successful overthrow of capitalism through socialist revolution? How can the programme of revolutionary communists become the programme of the masses? This was at the heart of The Transitional Programme.

In a discussion he held with the leaders of the American Trotskyists in March 1938, Trotsky explained that the aim was:

“…not to engage in abstract formulas, but to develop a concrete programme of action and demands in the sense that this transitional programme issues from the conditions of capitalist society today, but immediately leads over the limits of capitalism…

“These demands are transitory because they lead from the capitalist society to the proletarian revolution, a consequence in so far as they become the demands of the masses as the proletarian government.

“We can’t stop only with the day-to-day demands of the proletariat. We must give the most backward workers some concrete slogan that corresponds to their needs and that leads dialectically to the conquest of power.”

The essential idea is that the revolutionary party must start from the immediate problems facing the working class – from such questions as inflation, low wages, long working hours, expensive housing costs, healthcare costs, education, and so on.

It must not stop there, however. To do so would mean transforming the programme into the classic ‘minimum programme’ of the old Second International, which was disconnected from the ‘maximum programme’ of socialism. This would drag us down into the swamp of reformism.

No, the revolutionary party has the duty to start from the immediate problems, and raise demands that offer a solution – but always link these to the need for the working class to take power as the means of concretising those same demands.

We have to understand that the overthrow of capitalism through socialist revolution cannot be accomplished by a small organisation isolated from the mass of working people. It can only be carried out by the masses themselves.

As Marx explained: “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves.” He also explained that “theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses”.

Revolutionary consciousness

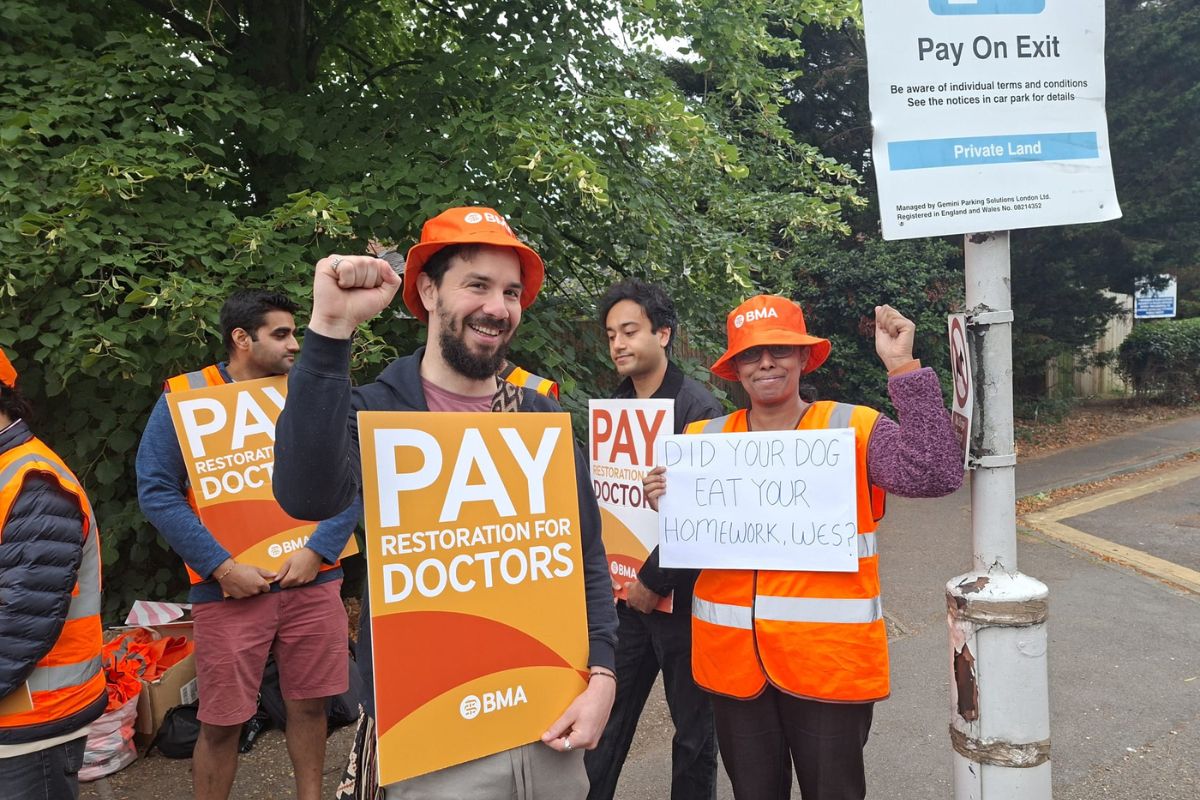

The working class is the class that can transform society. But it needs a clear understanding of the tasks before it. The working class also does not reach revolutionary conclusions overnight. The working class enters into struggle over its immediate demands in the workplace, and that is where revolutionary communists must start from.

We do not, however, limit ourselves solely to such demands. We participate shoulder-to-shoulder with the workers in their struggles. But we always raise the idea that, in the long run, it is capitalism that is the obstacle to them achieving a permanent solution to their problems.

The final victory of the socialist revolution would be unimaginable without the day-to-day struggles of the working class under capitalism. It is through such struggles that the working class begins to understand the true nature of the system they are up against.

Over time, and through many experiences, the workers begin to understand that this or that reform, this or that conquest, such as higher wages or a shorter working week, cannot be maintained without removing the capitalist system as a whole.

Revolutionary communists do not adopt a sectarian or ultra-left stance on such questions. What this means is that we do not stand aloof from the mass of working people. We do not belittle their lack of understanding of the need for social revolution and the overthrow of the capitalist system.

Communists understand that the mass of working-class people learn from experience. We therefore participate in the day-to-day struggles of the workers, going through the experience of their struggles. And at each stage, we base ourselves on the conclusions the workers are drawing, and use these to raise the general level of understanding.

At the same time, we do not sow any illusions in the system, but expose it in the eyes of the masses.

Demands

The Transitional Programme has demands that apply to different situations, taking into account the concrete conditions in each country. It has demands that apply to the conditions in developed capitalist countries; to industrialised countries, where workers are concentrated in large factories.

It also raises demands for those countries where industry is less developed, and where a large part of the population still lives in rural, peasant conditions. It raises specific demands that apply to fascist regimes, where democratic slogans could play a role in mobilising the masses.

It also has a section dedicated to the Soviet Union, where the Stalinist bureaucracy had usurped political power. Trotsky raised the need for ‘political revolution’: i.e. a revolution that maintained the conquests of October 1917 – a centralised planned economy – while reconquering power for the working class, as the only means of moving society forward to genuine communism.

The essence of transitional demands lies in their immediate relevance to the problems of the working class.

Faced with rampant inflation, the call for a sliding scale of wages answers the immediate problem of the falling value of wages. The call for a sliding scale of hours – or for a shorter working week, as we would pose it today – with no cut in wages, answers the problem of unemployment. If there aren’t enough jobs, then share the work out so all have jobs!

Transitional demands, however, do not stop at the immediate problems. They are linked to the fact that, if such demands are to be won and maintained, then the working class must pose itself the task of overthrowing the whole system through socialist revolution.

Moving beyond reformism

For many decades, the illusion that gradual reform of the capitalist system was possible dominated the working-class movement. This, however, has now started to break down.

After the financial crisis of 2008, we saw austerity measures imposed on the working class, as the capitalist class sought to bring down the unprecedented levels of debt that had built up over the previous period.

The impact of these policies can be summed up in one statistic: since 2009, the austerity measures applied across the European Union have left the average citizen of Europe €3,000 worse off in terms of real purchasing power. Everywhere, real disposable incomes have been drastically cut.

The pressure is relentless. It has been calculated that for the EU member states to achieve a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent – as established in a treaty they all signed up to – would require an annual cut of two percent of public spending every year until 2070.

This implies permanent austerity measures for two or three generations to come. It means not only significant falls in the real purchasing power of wages, but also destroying healthcare, education, social housing, pensions, etc. – i.e. everything that makes for a civilised existence.

The first reaction to this was seen in the period starting around 2014-15.

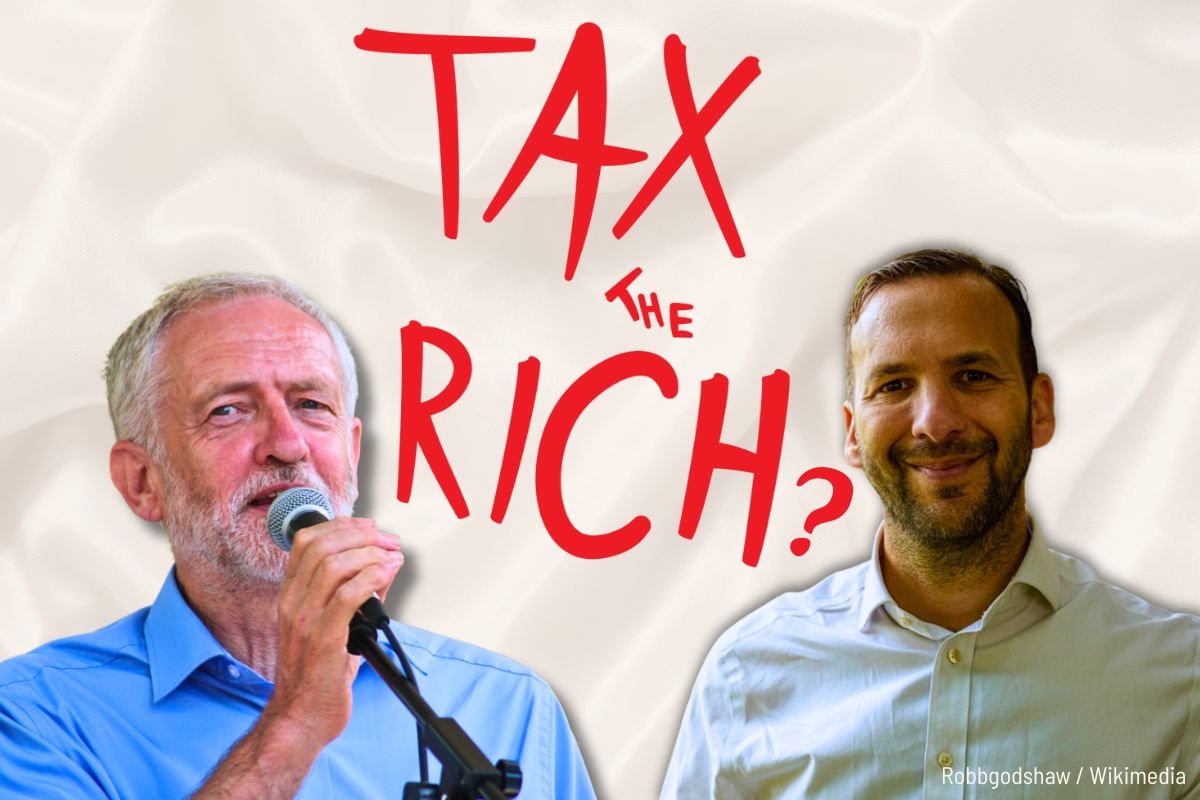

This was the period of the emergence of new political forces such as Podemos in Spain; the rise in popularity of formerly marginal parties, such as SYRIZA in Greece; the radical shift to the left in the Labour Party in Britain, which saw Jeremy Corbyn becoming the party leader. In the United States, a figure like Bernie Sanders – with all his talk about “a political revolution” against “the billionaire class” – became very popular.

Unfortunately, in one way or another, these figures and formations massively disappointed the millions of workers and youth who looked towards them. In Greece, the SYRIZA leaders formed a government and proceeded to carry out the very same policies that the masses had voted against.

In Spain, Podemos entered coalition governments that carried out the same policies. Corbyn, faced with a systematic onslaught from the right wing of the Labour Party, failed to fight back. In the US, Sanders completely capitulated to the Democratic Party establishment.

This led to widespread disappointment. But it also led to a layer – particularly among the youth – seeking answers as to why all this had happened. This explains the rise in popularity of the idea of communism.

In spite of all the propaganda of the mainstream media aimed at promoting the idea that communism is dead, that Marxism is a thing of the past with no relevance to the world of today, a huge layer of the youth see capitalism as the problem. And they are seeking an understanding of why society is in an impasse.

Revolutionary communism

It is in this context that many workers and youth are turning to the only rational and scientific explanation of the present crisis: the ideas of scientific socialism; of Marxism.

In spite of all attempts to prove that capitalism is the only possible form of society we can live in, it is capitalism in crisis that is pushing the most advanced and thinking layers of the youth and the working class to seek a revolutionary way out.

Karl Marx famously said that: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Marx was not dismissing philosophy, as such. Marxism is also a philosophical outlook. What he meant was that we do not limit ourselves to interpreting and analysing the world. We actively engage in fighting to change it.

That is the essence of revolutionary communism.

You can purchase Trotsky’s Transitional Programme here!