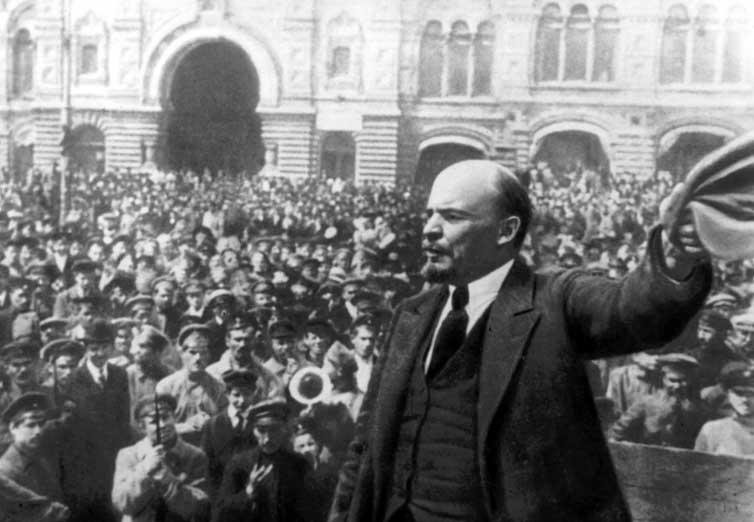

Written by Lenin in August-September 1917, The State and Revolution provides a definitive presentation of the Marxist theory of the state. Written in Lenin’s characteristically clear and incisive style, this book is a cornerstone of revolutionary Marxism.

Setting out the ideas of Marx and Engels on the state, and the position of the working class in relation to it, Lenin directs his fire at the “servile adaptation of the ‘leaders of socialism’ to the interests not only of ‘their’ national bourgeoisie, but of ‘their’ state”. Today this criticism retains its full force, when self-proclaimed “socialists” rush to support “their” own state in imperialist adventures around the world, and the interests of “their” bourgeoisie at home, whilst preaching pacifism and compromise to the workers.

In contrast to the anarchists however, Lenin does not simply call for the “abolition” of the state or the rejection of state power in and of itself. Following Marx’ and Engels’ conception of the dictatorship of the proletariat, Lenin calls for the dismantling of the bourgeois state and its replacement with a workers’ state directed at the expropriation and suppression of the bourgeoisie, without which the overthrow of class society, and with it the material basis for the “withering away” of the state would not be possible.

That the book was written in the midst of the Russian Revolution should not escape notice. As Lenin himself writes in the preface, “The question of the relation of the socialist proletarian revolution to the state… is acquiring not only practical political importance, but also the significance of a most urgent problem of the day, the problem of explaining to the masses what they will have to do before long to free themselves from capitalist tyranny.” Rather than trying to improvise his position on the spot, Lenin went directly to Marx and Engels, and drew up his revolutionary programme based on a serious approach to Marxist theory. It is this proud tradition which we must continue today.

Chapter 1: Class Society and the State

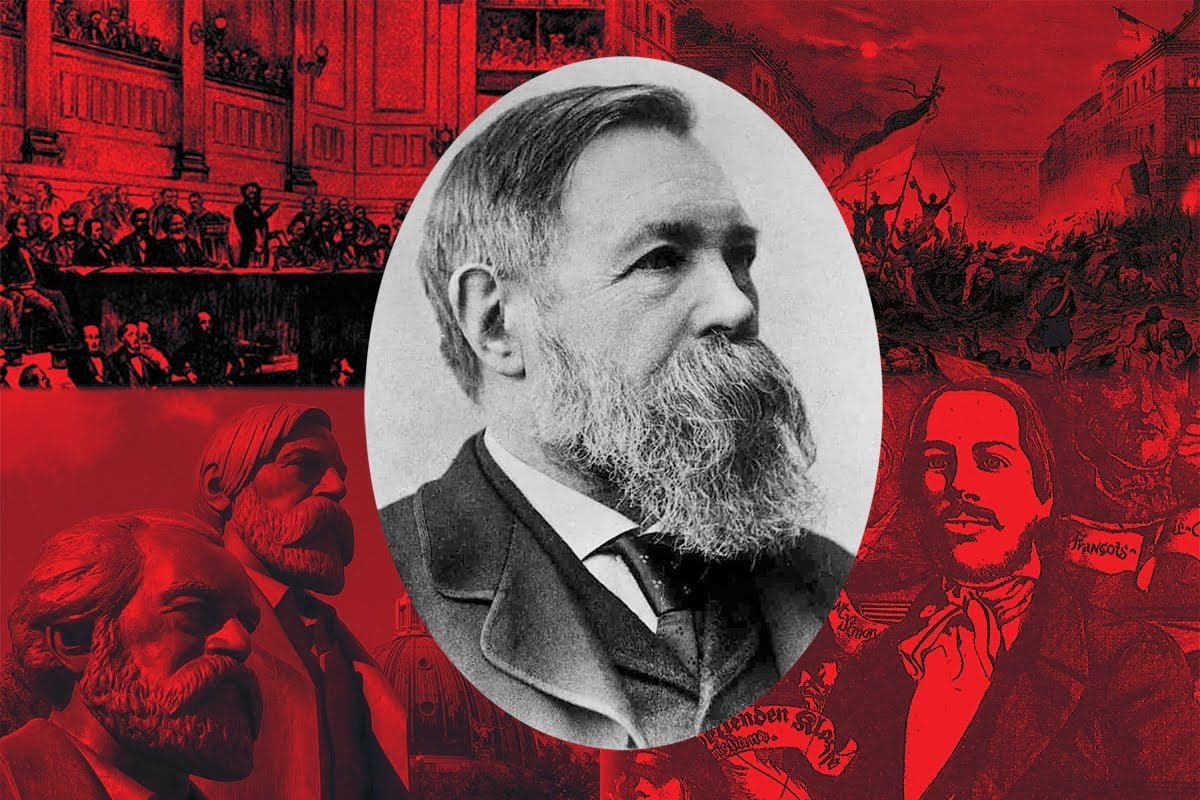

In the first chapter of the State and Revolution Lenin lays out the foundation for the rest of his arguments by letting Marx and (particularly) Engels speak for themselves on the origin and role of the state in society. Setting out a number of key quotes from Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State and Anti-Duhring, Lenin draws out the basic tenets of the Marxist position on the state, in opposition to the distortions of the “opportunists”, such as Karl Kautsky.

Splitting the chapter into four sections, Lenin sets out the following fundamental conclusions: that the state arose out of the division of society into classes; that it exists in order to impose the order of the ruling, possessor class over the exploited masses and not to “reconcile” the contending classes in society; that it relies on armed force to carry out this function; that in seizing power the proletariat abolishes this state and replaces it with the dictatorship of the proletariat, the fate of which is to “wither away” as class antagonisms are done away with; and that this is impossible without a violent revolution.

It is on the basis of these key ideas which Lenin goes on to analyse the historical experiences of other revolutions and further develop his position on the state. It is also precisely these ideas which constitute the dividing line between revolutionary Marxism and reformism.

Study questions:

- What is the state, and why does it exist?

- To what degree is the state independent of social classes?

- What does Engels mean when he says that in a democratic republic “wealth exercises its power indirectly, but all the more surely”?

- What position should Marxists take on universal suffrage?

- What does Engels mean by, “The state is not ‘abolished’. It withers away.”?

- What is the difference between a bourgeois and a workers’ state?

Chapter 2: The Experience of 1848-51

In this chapter Lenin goes on to look more closely at the development of Marx’ thought on the question of the state following the events of the French revolution of 1848 and the seizure of power by Louis Bonaparte in December 1851.

Lenin establishes on the basis of Marx’ pre-revolutionary writings, as well as his seminal Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, that the concept of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” is one which can be found consistently throughout Marx’ work, as opposed to the “peaceful development of democracy” claimed by the opportunists.

Describing the notion that the state can rise above the class struggle and persuade the minority to humbly submit to the majority as a “petty-bourgeois utopia”, Lenin argues that the essence of Marx’ conclusions on the state was the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Further, he demonstrates that Marx saw all previous revolutions as having only further perfected the state apparatus of the bourgeoisie (in the form of the ever expanding bureaucracy and army) and argued that the task of the proletarian revolution would be not to inherit the existing state but to smash it and replace it with the “proletariat organized as the ruling class”. What form that might take is the subject of the next chapter.

Study questions:

- What is the dictatorship of the proletariat? What is its purpose?

- Why can the overthrow of bourgeois rule only be accomplished by the proletariat?

- Why does the proletariat need a state at all?

- Why was the Russian Revolution compelled “to concentrate all its forces of destruction” on the bourgeois state created in February 1917?

- What is the difference between the recognition of the class struggle only and Marxism?

Chapter 3: Experience of the Paris Commune of 1871

In this chapter Lenin explores Marx’ treatment of the Paris Commune as the first experience of the working class “organised as the ruling class”, albeit for only a brief period.

Having established in the abstract that the working class cannot “simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes” and must instead “smash” the pre-existing bureaucratic apparatus, it was necessary for Marx (and future Marxists) to explain in more concrete terms what this apparatus should be replaced by. This explanation could only come from the real struggles of the working class, and it was the Paris Commune which provided Marx with the first ever example of the dictatorship of the proletariat in history.

Lenin sets out the key features of this workers’ state: the substitution of the “armed people” for the standing army; the election of all officials, including the police and judiciary, with the right of recall; the restriction of officials’ salaries to “workmen’s wages”; and the abolition of parliamentarism in favour of the establishment of workers’ councils electing delegates to a national assembly with both legislative and executive functions (and therefore more than just a “talking shop”). This provides a model for workers’ democracy to this day.

Study questions:

- What position did Marx take on the Paris Commune? How should this influence the approach we take to other revolutions?

- What for Lenin is the significance of Marx’ reference to the “people’s revolution”? How did this relate to the tasks of the Russian Revolution?

- Why did the Paris Commune fail?

- Why does Lenin say, “the transition from capitalism to socialism is impossible without a certain “reversion” to “primitive” democracy”?

- What is the difference between parliamentarism and workers’ democracy?

- Why is the immediate abolition of all bureaucracy “out of the question”?

Chapter 4: Supplementary Explanations by Engels

Lenin continues his Marxist analysis of the state in chapter 4 while making extensive use of quotes by Engels. He begins by making a clear distinction between a Marxist analysis and the views of the anarchists who do not see the state withering away but abolished overnight. The proletariat must use the state as a temporary means to overcome the inevitable resistance of the bourgeoisie. The anarchists would deny the working class this valuable means of defending the revolution.

He explains that the commune and all genuine worker’s states differ from all previously existing states in that they are for the first time used by the majority to repress a minority. Instead of being a special force standing above society it becomes representative of the majority of the population.

Lenin goes on to explain why Marxists are not neutral on the question of what the form bourgeois states take, a democratic republic is preferable to a despotic monarchy. Although the ideal form is a centralised democratic republic. However, this does not trump the national question.

In regard to the operating of the state Lenin makes clear the need to ensure that this does not belong to privileged officials. Instead it must be ensured that every individual contributes to the administration of the state. This is vital for the eventual withering away of the state.

Study questions:

- Why can the state not be abolished “within twenty-four hours”?

- Why is it not necessary to abolish certain functions and institutions of the state?

- Why is a democratic republic the best preparation for the dictatorship of the proletariat?

- Why are centralised states preferable to federal systems in most scenarios? How does this relate to the national question?

- How does the state, as Engels puts it, transform ‘the servants of society into the masters of society’?

- What does Lenin mean when he says that ‘the withering away of the state also means the withering away of democracy’?

Chapter 5: The Economic Basis of the Withering Away of the State

In this chapter Lenin deals with explaining the transition from capitalism to communism. This will invariably involve a political transitionary period wherein the dictatorship of the proletariat, once established, begins to wither away.

A socialist revolution entails the establishment of a more complete democracy. Many of the capitalist countries of the west are referred to as democracies, yet the majority of the population do not have the means to participate in actual politics beyond voting every few years. Whereas the capitalists can use their wealth and power to influence the state to a far greater extent than that of the average worker.

The need for a state would disappear as the conditions for its existence also disappeared. Instead of being coerced into following laws people will become accustomed to following the rules of social life.

Lenin proceeds by referring to Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, in which he draws a distinction between the lower phase of communist society (sometimes referred to as socialism), and the higher stage of communism. The emerging lower stage of communism still bears the birthmarks of the old capitalist society; while exploitation has been abolished, there is not yet full equality as distribution is still based on the amount of labour performed.

Once the capitalists have been expropriated it will be possible to achieve a massive development of the productive forces, it is on this basis that the highest stage of communist society could be realised. Only at this highest stage will the rule ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to their need’ be achieved.

Study questions:

- How do capitalists have more political influence than workers?

- How would the democracy of socialism differ from the democracy of capitalism?

- Why would the absence of classes entail a withering away of the state?

- Why, in a socialist society, would a worker not receive ‘the full product of his labour’ as Lassalle puts it?

- What does Lenin mean by ‘bourgeois right’ and why is it still present in the lower stage of communism?

Chapter 6: The Vulgarisation of Marxism by Opportunists

In the final chapter Lenin seeks to defend the revolutionary traditions of Marxism against those who downplay revolution in favour of reform. Lenin re-emphasises that the proletariat can neither take control of the bourgeois state nor refuse to use state power at all; it requires a state of its own to make use of.

Criticising the theorist Kautsky, Lenin argues that the task of a proletarian revolution would be to break up the bureaucracies of the bourgeois state, replacing all functionaries with elected workers, who are subject to recall and receive an average working wage. However, it would also be necessary to transition into a state where administration becomes a collective endeavour, such that ‘all become “bureaucrats” for a time, and no one, therefore, can become a “bureaucrat”’.

Kautsky distorts Marx’s position on the state – the proletariat’s conquest of state power is not achieved by simply governing the bourgeois state by parliamentary majority, but when the state’s class character changes such that the proletariat is organised as the ruling class, not the bourgeoisie. This can only be achieved by revolution.

Lenin explains that under capitalism society cannot function without a bureaucracy as the working masses are prevented from engaging in political activity. A loyal bureaucracy is one of the ways that the capitalists maintain control over the state. A shortened working day enables workers to engage in political activity and running of the state, thus depriving the capitalists of a bureaucracy they can control.

Unfortunately, Lenin was unable to finish the book due to the onset of the October Revolution. In the postscript he writes; ‘It is more pleasant and useful to go through the “experience of revolution” than to write about it.’

Study questions:

- How did Bernstein distort a quote from Marx which said; ‘the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes’?

- Why is it necessary to ensure that the task of administration is one that is shared by all workers?

- What does the term ‘centrism’ mean when used in a Marxist context?

- What are the three ways that Marxists and Anarchists differ according to Lenin?

- Why is there a risk of proletarian officials becoming ‘bureaucratised’ under capitalism?

- Why is it vital that any administrators are subject to election and recall by workers?