During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the working class showed all the determination, self-sacrifice, and organisational ability to carry out not one, but ten revolutions, as Trotsky stated. And yet they were ultimately frustrated – betrayed as they were by all their leaders.

Of these leaders, the Stalinists played the most counter-revolutionary role.

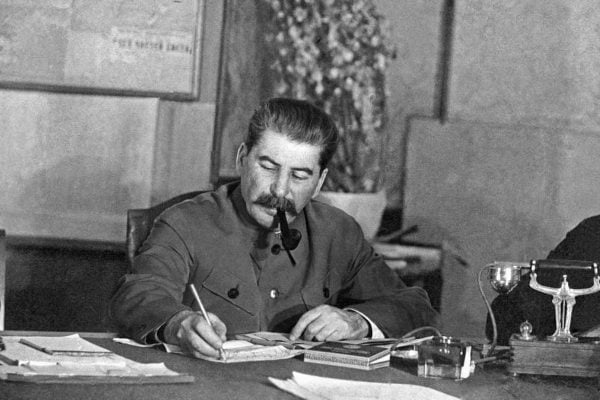

Joseph Stalin had usurped power from the working class in the Soviet Union and crushed its active vanguard. He represented the interests of the Soviet bureaucracy – a parasitic caste of privileged state administrators. This caste developed amidst the poverty, backwardness, and imperialist intervention that beset Russia after the revolution.

Not only did Stalinism play a reactionary role within the Soviet Union, but also abroad, including during the Spanish Civil War. This was owing to its influence over the international communist movement.

The Stalinist bureaucracy was inherently nationalistic. It identified its privileges with its control over the Soviet state. Revolutionary internationalism, it feared, might jeopardise the stability of the Soviet state and deteriorate relations with its neighbours.

Most importantly, the victory of revolution elsewhere would enthuse the Soviet working class, which in turn could threaten the Stalinists’ position at home and abroad. Therefore, rather than extend the revolution internationally, the Stalinists sought accommodation with capitalist powers such as Britain and France.

The Communist International, created in 1919 as the party of the world proletarian revolution, became a diplomatic lever in the hands of the Stalinist clique once they had taken over.

The bureaucracy’s narrow nationalism found ideological justification in Stalin’s ‘theory’ of ‘socialism in one country’. This treacherous policy represented a renunciation of Marxist internationalism, and led workers to defeat in countries such as Britain (1926), China (1927), and Germany (1933).

But, undoubtedly, the most gruesome Stalinist betrayal of a proletarian revolution took place during the Spanish Civil War in 1936-39. Here, Stalinism behaved not simply as a brake on the working class, but as a consciously and expressly counter-revolutionary force.

Sectarianism

On 14 April 1931, King Alfonso XIII fled Spain, and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed after a resounding victory of republican parties in local elections. Thus began the Spanish Revolution – the most sweeping revolutionary process in Europe since the Russian Revolution of 1917.

At this point, the official Spanish Communist Party (PCE) was a minuscule force, with some 800 members. The dominant forces of the Spanish workers’ movement were the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labour (CNT) and the social-democratic Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE).

Created as a unified organisation in November 1921, the PCE never acquired much traction. It languished throughout the 1920s, undermined by repression and infighting. As with other sections of the Communist International, it came under the iron control of Moscow and, consequently, of the Stalinists.

There were talented figures in the PCE’s ranks – men such as Andreu Nin, Maurín, Juan Andrade. But frequent purges and Moscow’s political zigzagging drew them away.

In 1931, pliable characters staffed the party – figures such as Mije, Ibárruri, and Díaz – who were incapable of thinking independently, and who were always ready to regurgitate the Kremlin’s latest phrase.

At this time, the Communist International was going through its so-called ‘third period’: an ultra-leftist phase that predicated irreconcilable war against the social democrats, who were termed ‘social-fascists’. In Germany, this sectarianism facilitated Hitler’s rise to power.

Following Moscow’s diktats, the PCE received the Republic with the slogan “down with the bourgeois Republic, all power to the soviets!”

This position was doubly wrong. Firstly, because the Republic initially enjoyed widespread support among the working class. Secondly, because there were naturally no soviets in Spain, nor could there be at this point.

The PCE was profoundly sectarian. This minuscule force denounced the PSOE as ‘social-fascist’ and the CNT as ‘anarcho-fascist’. The Stalinists created their own ersatz trade unions. The ultra-left PCE was initially left out of the trend towards workers’ unity of 1933-34.

Right-wing parties won the general elections of November 1933, which took place at a moment of deep disenchantment towards the reformist left and towards the Republic as a whole. The victory of the right, however, galvanised the labour movement, which became acutely aware of the fascist danger after the Nazis had come to power in Germany.

Twists and turns

A large segment of the PSOE veered sharply to the left. Left-wing organisations began to agitate for a united front, which crystallised in the Alianzas Obreras (Worker Alliances).

At first, the PCE turned its back on the Worker Alliances. However, Moscow suddenly demanded a change in tack. Hitler’s victory called into question the criminal sectarianism of ‘third period’ ultra-leftism.

Stalin was not only worried about the destruction of the German Communist Party, but – most importantly – about Hitler’s aggressive foreign policy, which directly threatened the Soviet state. Stalin therefore revised his international strategy.

After a phase of tension with Britain and France in 1927-33, Moscow sought rapprochement with western ‘democracies’ to stave off Germany.

The quest for an alliance with bourgeois democracies found an expression in the Communist International, which was instructed to collaborate with reformist and liberal forces, and to forgo revolutionary agitation in the name of ‘anti-fascist unity’.

In September 1934, the PCE was forced to revise its sectarianism. The yes-men in its leadership accepted this U-turn quite naturally.

The party therefore participated in the revolutionary general strike of October 1934, which took place after the far right was brought into the ruling coalition. However, as the Stalinists were very small, their entry made little difference.

More consequential was the rejection of the Worker Alliances by the anarchist CNT, which largely accounts for the failure of the uprising in most of Spain.

The events of October 1934 led to important realignments within the Spanish left. Above all, they raised the importance of unity.

The PCE now peddled an anti-fascist front and embraced a moderate line. It joined the socialist trade unions. It intervened in the Socialist Youth, which had swung far to the left in 1933-34.

The Stalinists came to dominate the entire organisation, gaining them a mass base for the first time.

This was possible thanks to the regrettable sectarianism of the Spanish Trotskyists, who the Socialist Youth leadership had invited to join and ‘help Bolshevise’ the movement. Instead, however, they chose to fuse with other small groups in order to form the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) – a decision Trotsky criticised harshly.

In Catalonia, the Stalinists joined various left-wing groups to form the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia. The PCE vigorously agitated for the Spanish Popular Front: a broad alliance of leftist and liberal parties with a tame reformist programme, which won the elections of February 1936.

Revolution and civil war

The Popular Front government stood for bourgeois law and order. Upon its victory, however, social agitation attained unprecedented intensity. This convinced the ruling class that bourgeois democracy could not hold back the workers. Dictatorship was necessary.

It was in this context that General Franco staged his coup d’état in July 1936. His putsch met the ferocious resistance of the masses. The defeat of the coup in key regions unleashed the social revolution: workers formed armed militias; took over factories and estates; set up barricade committees, etc.

Working-class organisations took charge of social and economic life, and administered it in the interests of the majority. They led the first military pushback against Franco. The revolutionary workers rallied behind them the poor peasantry and sectors of the middle class.

Consequently, the republican state was suspended mid-air. Whilst threatened by Franco, it was more fundamentally opposed to the power of the working class, which threatened capitalism as a whole. But thanks to the uprising of the workers, it was disorganised and deprived of its repressive apparatus.

Workers’ power was implicit in the situation. The task was to dismantle the remnants of the Republic, and to centralise local working-class organs into a new authority that would wage a revolutionary war against Franco.

The formation of a unified proletarian army became a burning mission of the revolution. To win, it needed to be organised on the principles of class consciousness and iron revolutionary discipline, rather than the hierarchies of bourgeois armies. And if based on a programme for social transformation, it could enthuse the masses and exploit the class contradictions of Franco’s army.

This is precisely what the Bolsheviks did upon the outbreak of civil war in Russia in 1918, when they created the Red Army.

In Spain, however, no organisation was up to the task. The anarchists refused to take power, and chose to cooperate with the bourgeois Republican authorities, joining the government in November. The PSOE leftists also chose collaboration, taking over the government in September. Even the dissident communists of the POUM entered the Catalan cabinet.

Thus began the slow reconstruction of the bourgeois state machine. Civil war demands centralised authority. The refusal of the anarchists and socialists to build such an authority on a revolutionary basis left a vacuum that had to be filled. It was filled by the old bourgeois state, with the support of the Stalinists.

Yet this process came up against the scattered workers’ power that had crystallised during the fighting in July. It could only be imposed through civil war within the civil war.

Historian Hugh Thomas rightly labelled the Spanish Civil War the “war of two counterrevolutions”: the Francoist and the democratic-republican.

The Stalinists – owing to their ruthlessness, single-mindedness, and Soviet backing – emerged as the main battering ram of the republican counter-revolution.

Moscow’s role

Moscow saw the Iberian Peninsula not as the setting of a sweeping proletarian revolution, but as part of a diplomatic chessboard.

Stalin’s main priority in 1936 was to woo British and French imperialism into an alliance against Germany. For this, the Soviet Union had to present itself as a respectable ally that would not jeopardise British and French capitalist interests.

Events in Spain upset his plans. Therefore, Stalin sought to throttle the Spanish Revolution as a sacrificial lamb, sending a clear message to London and Paris about Soviet ‘trustworthiness’.

On March 20, 1937, Stalin stated: “The Spanish people are in no condition now to bring about a proletarian revolution – the internal and especially the international situation do not favour it.”

Soviet efforts to draw Britain and France into an alliance and to convince them to support the Spanish Republic, however, came to naught.

Fernando Claudín, a PCE leader who later on came to criticise the party’s wartime strategy, rightly commented:

“The ‘Western governments’, unlike the Communist International, saw the question in class terms, and realised the most reliable representative of Spanish capitalism was not [Social Democratic Prime Minister] Negrín, but Franco”.

Paris and London preferred to reach a deal with Hitler in Munich in October 1938. Thereafter, Stalin struck his own alliance with Hitler in August 1939.

Diplomatic combinations – struck with the imperialists on the ashes of the Spanish Revolution – could not have averted the rise of fascism and the barbarism of world war. But a victorious revolution in Spain would have delivered a devastating blow to world fascism.

Disarming the revolution

Stalin used Soviet aid to the Republic as a political bargaining chip, in order to push the republican government rightwards. The isolation of Spain’s anti-fascists facilitated this task, as only the Soviet Union and Mexico sold weapons to the Republic.

The Moscow-controlled International Brigades mobilised tens of thousands of volunteers, who fought courageously in Spain. But these were also used by the Stalinists as a tool to enhance Soviet leverage.

At the same time, the International Brigades revealed that the only friend of the Spanish fighters was international working-class solidarity, not the British and French imperialists.

The PCE and their puppeteers in Moscow adopted an openly Menshevik policy in Spain. José Díaz, following Soviet instructions, explained that: “There can be no question at present of a dictatorship of the proletariat or of Socialism, but only of the struggle of democracy against Fascism.”

Stalinists claimed that the Spanish revolution was a struggle against feudalism and German-Italian intervention; a bourgeois revolution for democracy and national independence. Yet most Spanish bourgeois had fled to Franco’s side in July, or had been shot!

For the Stalinists, socialism was a distant goal, possible only after a prolonged phase of bourgeois-democratic evolution.

This was a word-for-word repetition of the Russian Menshevik programme. The Spanish ‘Communist’ Party was communist only in name. It became a furious enemy of anything that smacked of Bolshevism – which it labelled, rightly or wrongly, as Trotskyism.

In their public propaganda in the early months of the war, however, the Stalinists used a slightly different argument: win the war first, then do the revolution. Yet this mechanistic formula missed the entire point. As anarchist Camilo Berneri rightly put it: “The only dilemma is as follows – either victory over Franco through revolutionary war, or defeat.”

Crackdown

The Stalinists became entrenched in the reorganised Republican army and police. Utilising their growing institutional power, the PCE cracked down on the militias; dissolved farming and factory collectives, handing their property back to former owners; and replaced the workers’ committees with Republican institutions.

The Stalinists’ defence of bourgeois legality won them a large following among the petty bourgeoisie that had been spooked by the events of July 1936. In Madrid, out of over 60,000 PCE members, only 10,000 belonged to trade unions, which gives an idea of its social composition.

Initially, this counter-revolution took the form of isolated skirmishes. However, in May 1937 this camouflaged civil war took the form of an open showdown.

On 3 May 1937, a Stalinist-controlled detachment of the Republican police attempted to evict the CNT from Barcelona’s telephone exchange. Its takeover by the workers in 1936 was an important conquest of the revolution – symbolically but also practically, as they could listen in to government communications. This clash therefore had major repercussions.

The Barcelona working class reacted to this attack through a spontaneous uprising. The following day, nine-tenths of the city was in the hands of the rebels. But despite the overwhelming power of the insurrection, the workers lacked leadership. The CNT and POUM leaders called on the rebels to abandon the barricades. The insurrection fizzled out.

Stalinist counter-revolution

A wave of counter-revolutionary violence followed the May events. Under pressure from the PCE and Soviet diplomacy, the POUM was banned. Stalinist agents kidnapped, tortured, and shot its leader, Andreu Nin. Many others were killed, including the aforementioned Berneri.

The Stalinists created a climate of terror. The Republican army and police and Stalinist armed groups crushed whatever remained of workers’ power.

In Aragon, one of the strongholds of the Spanish revolution, the regional Defence Council, which operated de facto as a workers’ government, was dissolved by a Stalinist army. The Council’s leader, anarchist Joaquín Ascaso, was jailed on sham accusations. The Civil War now became a conventional war for the defence of republican legality.

The Stalinists emerged as a mass force, boasting a million members in June 1937. This owed to factors such as PCE identification with Soviet aid, the recruitment of frightened petty bourgeois, and repression.

The main factor for Stalinist supremacy, however, was the disorientation of their opponents. The CNT, the POUM, and the PSOE leftists failed to present a credible solution to the question of power.

Since no major organisation defended a serious plan for a revolutionary war based on a new workers’ regime, the entire logic of the Civil War tacked towards the defence of bourgeois-republican order.

The Stalinists were the most consequential supporters of this strategy, which, moreover, they covered with leftist glitter and the prestige of the Soviet state. They stood out as the best-organised and most committed fighters in the war. They thus attracted many honest workers.

Defeat

After May 1937, the revolutionary energy that had beaten back Franco in July 1936 dissipated. A mood of apathy set in. Under these conditions, the fascists began to recover ground.

In March 1939, professional republican army officers around General Casado staged a coup. They cracked down on the Stalinists and opened up the remaining republican territory to the Francoists.

The coup was preceded by months of growing isolation of the PCE. Having accomplished the dirty work of destroying the revolution, the Stalinists were marginalised by their defeatist republican peers.

Fernando Claudín summed up the sad history of the Stalinists in 1936-39:

“In the first phase, the republicans, the socialists, the reformists, and the communists managed to beat back the revolution, hemming it within bourgeois-democratic bounds, and restored, on this basis, the republican state […]. In the second phase, the front of reformist socialists and republicans methodically strove to drive the communists out of the state apparatus […] and prepared the final capitulation.”

Franco’s victory was the tragic denouement of a war that had begun as a proletarian revolution that galvanised the masses, but, due to the Stalinist-reformist counterrevolution, ended as a conventional war for the defence of a discredited bourgeois regime.

As a rank-and-file PCE combatant, peasant Timoteo Ruiz, later reflected:

“Fighting and dying, we sometimes thought: All this – and for what? Was it to return to what we had known before? If that was the case then it was hardly worth fighting for. The shamefaced way of making the revolution demoralised people; they didn’t understand.”