The Paris Commune was one of the greatest episodes in the history of the French working class. Between the uprising of March 18 and the “Bloody Week” at the end of May, Paris was ruled by the democratic organs of the workers, who attempted to reorganise society on an entirely new basis – without exploitation or oppression. The lessons of these events are still very relevant today.

Twenty years earlier, Napoleon III had seized power during the military coup of 2 December 1851. At first, his regime seemed unshakeable. The workers’ organisations were repressed. But by the end of the 1860s the imperial regime was being seriously weakened by the exhaustion of economic growth, the repercussions of wars (in Italy, Crimea, Mexico) and the resurgence of the labour movement. Only a new war – and a rapid victory – could delay the fall of ‘Napoleon the Little’. In July 1870 he declared war on Bismarck’s Prussia.

War and revolution

War often leads to revolution. And for good reason: war suddenly tears people away from their daily routine and throws them into the arena of great historical events. The masses examine the behaviour of heads of state, generals and politicians much more carefully than in peacetime. This is especially true in the event of a defeat. However, the military offensive launched by Napoleon III quickly turned into a fiasco. On 2 September, near Sedan, the Emperor was arrested by Bismarck’s army, along with 75,000 soldiers. In Paris, massive demonstrations demanded the end of the Empire and the proclamation of a democratic Republic.

War often leads to revolution. And for good reason: war suddenly tears people away from their daily routine and throws them into the arena of great historical events. The masses examine the behaviour of heads of state, generals and politicians much more carefully than in peacetime. This is especially true in the event of a defeat. However, the military offensive launched by Napoleon III quickly turned into a fiasco. On 2 September, near Sedan, the Emperor was arrested by Bismarck’s army, along with 75,000 soldiers. In Paris, massive demonstrations demanded the end of the Empire and the proclamation of a democratic Republic.

Under this pressure from the streets, the ‘moderate’ republican opposition proclaimed the Republic on 4 September. A “Government of National Defence” was installed. Foreign Minister, bourgeois Republican Jules Favre pompously declared that “not an inch of land and not a stone of our fortresses” would be ceded to the Prussians.

German troops quickly surrounded Paris and placed the city under siege. At first, the Parisian working class gave its support to the new government, in the name of ‘unity’ against the foreign enemy. But the subsequent course of events shattered this unity and brought to light the conflicting class interests it had concealed.

In reality, the Government of National Defence did not believe it was possible or even desirable to defend Paris. In addition to the regular army, a 200,000 strong militia – the National Guard – declared itself ready to defend the city. But these armed workers of Paris posed a far greater threat to the interests of the French capitalists than the foreign army at the gates of the city. The government thought it best to capitulate as soon as possible to Bismarck. However, given the combative stance of the National Guard, the government could not publicly declare its intentions. The Minister and General, Trochu, counted on the economic and social effects of the siege to break the resistance of the Parisian workers. The government wanted to buy time; while declaring itself in favour of defending Paris, it entered into secret negotiations with Bismarck.

As the weeks went by, the hostility of the Parisian workers towards the government increased. Rumours were circulating about negotiations with Bismarck. On 8 October, the fall of Metz sparked a new mass demonstration. On 31 October, several contingents of the National Guard attacked and temporarily occupied the Town Hall. At this point, however, the mass of workers was not yet ready for a decisive offensive against the government. Isolated, the insurrection quickly ran out of steam.

In Paris, the siege had disastrous consequences. It was an urgent task to break it. After the failure of the retreat to the village of Buzenval on 19 January 1871, General Trochu had no other choice but to resign. He was replaced by Vinoy, who immediately declared that it was no longer possible to defeat the Prussians. It was clear to everyone now that the government wanted to capitulate – which it did on 27 January.

The Parisians and the Peasants

In the National Assembly elections in February, the votes of the peasantry gave an overwhelming majority to the monarchist and conservative candidates. The new Assembly appointed Adolphe Thiers – a hardened reactionary – as head of government. A conflict between Paris and the ‘rural’ assembly was inevitable. But in raising its head, the counter-revolutionary danger gave a powerful impetus to the Parisian revolution. The armed demonstrations of the National Guard multiplied, massively supported by the poorest layers of the population. The armed workers denounced Thiers and the monarchists as traitors and called for an all-out war for the defence of the Republic.

In the National Assembly elections in February, the votes of the peasantry gave an overwhelming majority to the monarchist and conservative candidates. The new Assembly appointed Adolphe Thiers – a hardened reactionary – as head of government. A conflict between Paris and the ‘rural’ assembly was inevitable. But in raising its head, the counter-revolutionary danger gave a powerful impetus to the Parisian revolution. The armed demonstrations of the National Guard multiplied, massively supported by the poorest layers of the population. The armed workers denounced Thiers and the monarchists as traitors and called for an all-out war for the defence of the Republic.

The National Assembly constantly provoked the Parisians. The siege had put many workers out of work; the indemnities paid to the National Guards were all that separated them from famine. However, the government abolished the allowances paid to each guard who could not prove that he was unable to work. He also decreed that rent arrears and all debts were to be paid within 48 hours. These and other measures hit the poorest hardest, but also led to the radicalisation of the middle classes.

The government’s surrender to Bismarck and the threat of a monarchist restoration led to a transformation of the National Guard. A ‘Central Committee of the Federation of the National Guard’ was elected, representing 215 battalions equipped with 2,000 cannons and 450,000 rifles. New statutes were adopted, stipulating “the absolute right of the National Guards to elect their leaders and to dismiss them as soon as they lose the confidence of their voters”. This Central Committee, and the corresponding structures at the battalion level, prefigured the soviets of workers and soldiers which appeared in Russia during the revolutions of 1905 and 1917.

The new leadership of the National Guard soon had the opportunity to test its authority. As the Prussian army prepared to enter Paris, tens of thousands of armed Parisians gathered with the intention of attacking the invaders. The Central Committee intervened to prevent a fight for which it was not yet prepared. By imposing its will on this issue, the Central Committee demonstrated that its authority was recognised by the majority of the National Guard and Parisians. Prussian forces occupied part of the city for two days, then withdrew.

18 March

To the ‘rural people’ of the Assembly, Thiers had promised the restoration of the monarchy. But his immediate task was to put an end to the situation of dual power that existed in Paris. The guns under the control of the National Guard – and in particular those of the heights of Montmartre – symbolised the threat posed to the capitalist order. On 18 March, at 3 am, 20,000 soldiers and gendarmes were sent, under the command of General Lecomte, to seize these guns. This was done without too much difficulty. However, the expedition commanders did not think about the couplings needed to move the guns. At 7 o’clock, the teams had still not arrived. In his Histoire de la Commune, Lepelletier describes what happened:

To the ‘rural people’ of the Assembly, Thiers had promised the restoration of the monarchy. But his immediate task was to put an end to the situation of dual power that existed in Paris. The guns under the control of the National Guard – and in particular those of the heights of Montmartre – symbolised the threat posed to the capitalist order. On 18 March, at 3 am, 20,000 soldiers and gendarmes were sent, under the command of General Lecomte, to seize these guns. This was done without too much difficulty. However, the expedition commanders did not think about the couplings needed to move the guns. At 7 o’clock, the teams had still not arrived. In his Histoire de la Commune, Lepelletier describes what happened:

“Soon after the alarm started ringing and we heard, in Clignancourt road, the drums playing a marching beat. Quickly, it was like a change of scenery in a theater: all the streets leading to the Butte were filled with a quivering crowd. Women formed the majority; there were also children. Isolated national guards came out in arms and headed for the Chateau-Rouge.”

The soldiers were surrounded by an ever-growing crowd. The inhabitants of the district, national guardsmen and the men of Lecomte were pressed against each other. Some soldiers fraternised openly with the guards. In a desperate attempt to reassert his authority, Lecomte ordered his men to shoot at the crowd. No one fired. The soldiers and the national guardsmen then cheered and hugged each other. Very quickly, Lecomte and Clément Thomas were arrested. Angry soldiers executed them shortly after. It hadn’t been forgotten that Clément Thomas had fired on insurgent workers in June 1848.

Thiers had not foreseen the defection of the troops. In a panic, he fled from Paris. He ordered the army and the administration to completely evacuate the city and its surrounding forts. He wanted to keep the army as far away as possible from revolutionary ‘contagion’. Some of the soldiers – some openly insubordinate, chanting revolutionary slogans – retreated in disorder towards Versailles.

With the collapse of the old state apparatus in Paris, the National Guard took all the strategic points of the city without encountering significant resistance. The Central Committee had played no role in these events. And yet, on the evening of 18 March it discovered that, despite itself, it had become the de facto government of a new revolutionary regime based on the armed power of the National Guard.

Vacillations of the Central Committee

The first task that the majority of the members of the Central Committee set for themselves was to get rid of power. After all, they said, we don’t have a ‘legal mandate’ to rule! After long discussions, the Central Committee reluctantly agreed to remain at the Town Hall for the “few days” necessary for municipal (communal) elections to be organised.

The first task that the majority of the members of the Central Committee set for themselves was to get rid of power. After all, they said, we don’t have a ‘legal mandate’ to rule! After long discussions, the Central Committee reluctantly agreed to remain at the Town Hall for the “few days” necessary for municipal (communal) elections to be organised.

The immediate problem facing the Central Committee was the army en route to Versailles under the leadership of Thiers. Eudes and Duval proposed to have the National Guard immediately march on Versailles, so as to break what was left of the forces at Thiers’ disposal. They were not listened to however. The majority of the Central Committee considered it preferable not to “appear as the aggressors”. The Central Committee was composed, in its majority, of honest men, but men who were far too moderate.

The energy of the Central Committee was absorbed in long negotiations on the date and methods of the upcoming municipal elections. They were finally fixed for 26 March. Thiers used this precious time to his advantage. With the help of Bismarck, the army gathered at Versailles was massively reinforced by fresh troops and weapons, with the aim of launching an attack on Paris.

On the eve of the elections, the Central Committee of the National Guard issued a remarkable declaration which sums up the spirit of self-sacrifice and integrity that was characteristic of the new regime:

“Our mission is over. We are going to give way in our Town Hall to your new elected representatives, to your regular representatives.”

The Central Committee had only one instruction to give to the voters:

“Do not lose sight of the fact that the men who will serve you best are those you will choose among you, living your own life, suffering from the same ills. Beware of the ambitious and upstarts […] Beware of talkers, incapable of taking action […]”

The programme of the Commune

The newly elected Commune replaced the command of the National Guard as the official government of revolutionary Paris. The majority of its 90 members can be described as left-wing Republicans. The militants of the International Workingmen’s Association (led by Karl Marx, among others) and the Blanquists (who were energetic but politically confused) together represented nearly a quarter of the elected officials of the Commune. The few right-wingers who were elected resigned from their posts on various pretexts.

The newly elected Commune replaced the command of the National Guard as the official government of revolutionary Paris. The majority of its 90 members can be described as left-wing Republicans. The militants of the International Workingmen’s Association (led by Karl Marx, among others) and the Blanquists (who were energetic but politically confused) together represented nearly a quarter of the elected officials of the Commune. The few right-wingers who were elected resigned from their posts on various pretexts.

Under the Commune, all the privileges of senior state officials were abolished. In particular, it was decreed that they should not receive more for their service than the wage of a skilled worker. They were also made recallable at any time.

Rents were frozen. The abandoned factories were placed under the control of the workers. Measures were taken to limit night work and guarantee the subsistence of the poor and the sick. The Commune declared that it wanted to “put an end to anarchic and ruinous competition between workers for the benefit of the capitalists”. The National Guard was open to all men fit for military service and organised on strictly democratic principles. Standing armies “separate and apart from the people” were declared illegal.

The Church was separated from the state and religion declared a private matter. Housing and public buildings were requisitioned for the homeless, public education was opened to all, as well as places of culture and learning. Foreign workers were seen as allies in the struggle for a ‘universal republic’. Meetings were held day and night; thousands of ordinary men and women were discussing how different aspects of social life should be organised in the interest of the common good. The characteristics of the new society which was taking shape in Paris were clearly socialist.

The defeat

It is true that the Communards made many mistakes. Marx and Engels rightly reproached them for not having taken control of the Banque de France, which continued to pay millions of francs to Thiers to pay for the arming and reorganisation of his forces.

It is true that the Communards made many mistakes. Marx and Engels rightly reproached them for not having taken control of the Banque de France, which continued to pay millions of francs to Thiers to pay for the arming and reorganisation of his forces.

Likewise, the threat from the Versaillaises was clearly underestimated by the Communards. Not only was no attempt made to attack Versailles – at least until the first week of April – but no attempts were made to even prepare a serious defence. On 2 April, a Communard detachment heading towards Courbevoie was attacked and pushed back towards Paris. The prisoners in the hands of the forces of Thiers were executed. The next day, under pressure from the National Guard, the Commune launched an attack on Versailles. But despite the enthusiasm of the Communard battalions, the lack of military and political preparation condemned this late attempt to failure. The leaders of the Commune believed that, as on 18 March, the Versailles army would rally to the Commune at the mere sight of the National Guard. It did not.

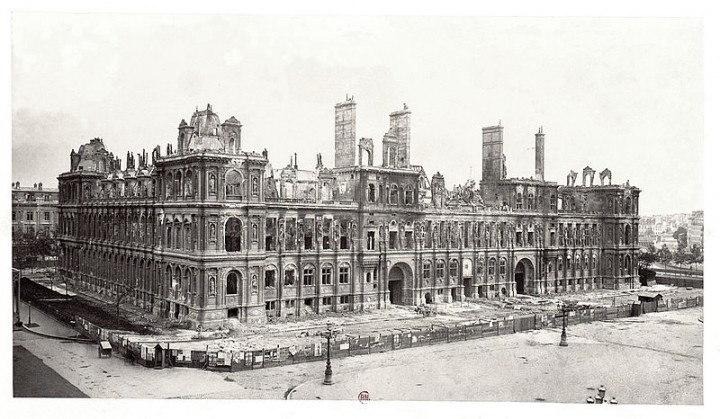

This setback caused a wave of defeatism to sweep over Paris. The resolute optimism of the first weeks gave way to a mood of impending defeat, which accentuated divisions at all levels of military command. Finally, the Versailles army entered Paris on 21 May. At the Town Hall, the Commune was deprived, at the decisive moment, of a serious military strategy. It simply ceased to exist, abdicating all its responsibilities in favour of a totally ineffective Committee of Public Safety.

The National Guards were posted in their own districts, without any centralised command. This decision prevented any concentration of Communal forces capable of resisting the thrust of the Versailles troops. The Communards fought with immense courage but were gradually pushed back to the east of the city, and finally defeated on 28 May. The last Communards who resisted were shot at the 20th arrondissement, the ‘Federated Wall’, which can still be seen at Père Lachaise cemetery. During “Bloody Week”, Thiers’ forces massacred at least 30,000 men, women and children, claiming another 20,000 victims in the following weeks.

The workers’ state

The Paris Commune was the first workers’ government in history. In The Civil War in France, Marx explained that the Commune had proved that the workers cannot “simply lay hold on the existent state body and wield this ready-made agency for their own purpose. The first condition for the holding of political power, is to (…) destroy this instrument of class rule.” The Communards precisely attempted to build a new, workers’ state on the ruins of the old capitalist state in Paris. In doing so, they showed the basic characteristics of a workers’ state: doing away with bureaucracy; with an army separate from the people; with privileged officials; the introduction of election and recallability of all officials, etc.

The Communards didn’t have time to consolidate their power. Their isolation in a largely peasant nation was fatal to them. Today, on the contrary, the majority of people in society are wage workers. The economic foundations of the socialist revolution are much more mature than they were in the 19th century. It is up to us therefore, to bring about the free and democratic, socialist society for which the Communards fought and died.