With just over one week to go until the national conference of the Marxist Student Federation, we publish here a video and article about the life and ideas of Lenin. Join us at this year’s MSF conference to celebrate the centenary of the Russian Revolution and discuss how we can fight for revolution today!

With just over one week to go until the fourth national conference of the Marxist Student Federation – taking place at UCL, London on Saturday 11th February – we publish below a video and article about the life and ideas of Lenin. Join us at this year’s MSF conference to celebrate the centenary of the Russian Revolution and discuss how we can fight for revolution today!

Sign up for the MSF conference 2017

Follow the Marxist Student Federation on Twitter (@MarxistStudent) for regular updates and on Instagram (Marxist Student) to see the behind the scenes build up to the conference.

The full agenda for the conference is below:

10:30-11:00 – Registration

11:00-13:00 – In Defence of Lenin

14:00-15:30 – Building the forces of Marxism on campus and beyond

15:45-17:15 – Internationalism in action

17:15-17:30 – Closing remarks

18:30-23:00 – Social

We’re asking for a donation of £5 from all attendees at the conference to help the MSF build up Marxist societies in existing and new schools, colleges and universities.

In Defence of Lenin

By Rob Sewell

On 21st January 1924, Vladimir Lenin, the great Marxist and leader of the Russian Revolution, died from complications arising from an earlier assassin’s bullet. Ever since then there has been a sustained campaign to slander his name and distort his ideas, ranging from bourgeois historians and apologists to various reformists, liberals and assorted anarchists. Their task has been to discredit Lenin, Marxism and the Russian Revolution in the interests of the “democratic” rule of bankers and capitalists.

[See also this article from 2004 for more on the real history of Lenin and Bolshevism]

A recent history by Professor Robert Service, “Lenin: A Political Life, The Iron Ring”, states that:

“Although this volume is intended as a balanced [!], multifaceted account, nobody can write detachedly about Lenin. His intolerance and repressiveness continues to appal me.”

Another “balanced” historian, Anthony Read, goes so far as to assert, without any actual evidence, that Lenin was in a minority at the 1903 Party Congress, and simply chose the name “Bolsheviks” (the Russian word for majority) as “Lenin never missed a chance of furthering the illusion of power. From its very beginning, therefore, Bolshevism was founded on a lie, setting a precedent that was to be followed for the next ninety years.”

Mr Read continues with his diatribe: “Lenin had no time for democracy, no confidence in the masses and no scruples about the use of violence.” (The World on Fire, 1919 and the Battle with Bolshevism, pp.3-4, Jonathan Cape, 2008)

There is nothing new in such false claims which rely, not on the writings of Lenin, but heavily on the outpourings of Professors Orlando Figes and Robert Service, two “experts” on the “evils” of Lenin and the Russian revolution. Full of bile, they all peddle the lie that Lenin somehow created Stalinism.

Likewise, the Stalinists, having turned Lenin into a harmless icon, also defamed his ideas to serve their crimes and betrayals. Lenin’s widow, Krupskaya, was fond of quoting his words:

“There have been occasions in history when the teachings of great revolutionaries have been distorted after their death. Men have made them into harmless icons, and, while honouring their name, they blunted the revolutionary edge of their teaching.”

In 1926, Krupskaya, said that “if Lenin was alive, he would be in one of Stalin’s prisons.”

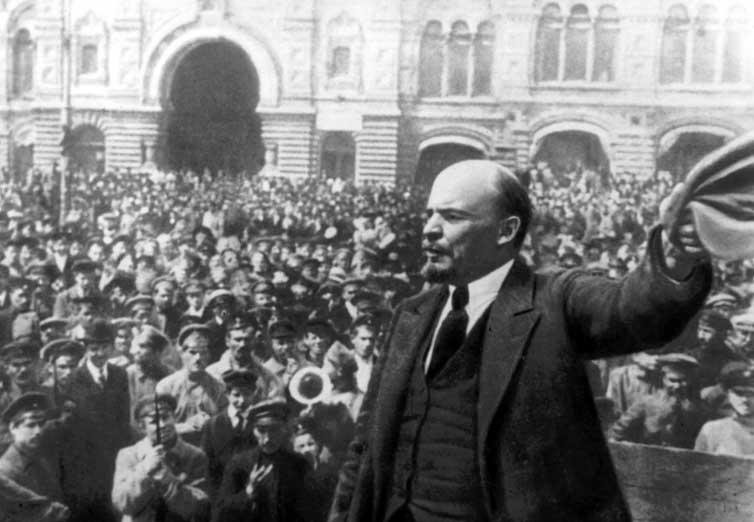

Lenin was without doubt one of the greatest revolutionaries of our time, whose efforts culminated in the victory of October 1917 and whose work changed the course of world history. The socialist revolution was transformed by Lenin from words into deeds. He became overnight “the most hated and most loved man on earth.”

Lenin’s youth

Born in Simbirsk on the Volga in 1870, Lenin was to experience a time of great upheaval in Russia. The semi-feudal country was ruled by Tsarist despotism. The revolutionary intelligentsia, faced with this despotism, were attracted to the terrorist methods of the Peoples’ Will. Indeed, Lenin’s elder brother, Alexander, was hanged for his part in the attempted assassination of Tsar Alexander III.

Following this tragedy, Lenin entered university and was soon expelled for his activities. This increased his political thirst and led to his eventual contact with Marxist circles. This progressed to a study of Marx’s Capital, which was circulating in small numbers, and then on to Anti-Duhring by Engels.

He got in touch with the exiled Emancipation of Labour Group, headed by George Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism, who he considered to be his spiritual father. He them moved, at the age of 23, from Samara to St Petersburg to form one of the first Marxist groups.

“It is thus, between his brother’s execution and his move to St Petersburg, in these simultaneously short and long six years of stubborn work, that the future Lenin was formed”, explained Trotsky. “All the fundamental features of his personality, his outlook on life, and his mode of action were already formed during the interval between the seventeenth and twenty-third years of his life.”

Massive foreign investment gave a spur to the development of capitalism and the emergence of a small virgin working class. The emergence of study circles and the impact of Marxist ideas saw attempts to establish a revolutionary Russian Social Democratic Party.

Lenin had met with Plekhanov in Switzerland in 1895 and on his return he was arrested, imprisoned, and then exiled. The first Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) was held in 1898, but the Congress was raided and the participants arrested.

Marxism and Bolshevism

At the end of his exile, Lenin concentrated his efforts on the establishment of a Marxist newspaper – Iskra, the ‘Spark’. By this means, Iskra was to establish Marxism as the dominant force on the left. Smuggled back into Russia it served to unite the circles into a unified national party on solid political and theoretical foundations.

At the end of his exile, Lenin concentrated his efforts on the establishment of a Marxist newspaper – Iskra, the ‘Spark’. By this means, Iskra was to establish Marxism as the dominant force on the left. Smuggled back into Russia it served to unite the circles into a unified national party on solid political and theoretical foundations.

In this period, Lenin wrote his famous pamphlet What is To Be Done?, which argued for a party made up of professional revolutionaries, people dedicated to the cause.

In 1903, the Second Congress of the RSDLP was held, which was essentially the founding Congress. It was here that the comrades of Iskra established themselves as the dominant trend in the party. However, an open split took place late in the proceedings over organisational questions between Lenin and Martov, both editors of Iskra. The Majority around Lenin became known as the “Bolsheviks” and the Minority around Martov as the “Mensheviks”.

There are many myths surrounding this split, which took most participants by surprise, including Lenin. There were no political disagreements at that time. These would only emerge later. Lenin attempted reconciliation between the factions, but failed. He later characterised the split as an “anticipation” of later important differences.

These differences emerged over the perspectives for the revolution in Russia. All tendencies viewed the coming revolution as “bourgeois-democratic”, namely a means of sweeping away the old feudal regime and clearing the path for capitalist development. The Mensheviks, however, stated that in this revolution, the workers would need to subordinate themselves to the leadership of the bourgeoisie. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, believed that the liberal bourgeoisie could not lead the revolution as they were tied to landlordism and imperialism, therefore the workers should lead the revolution supported by the peasants. They would form a “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”, which would provoke the socialist revolution in the West. In turn, this would come to the aid of the Russian revolution. Trotsky held a third view: he agreed with Lenin that the workers would lead the revolution, but believed they should not stop half way, but should continue with socialist measures, as the beginning of a world socialist revolution. In the end, the events of 1917 confirmed Trotsky’s prognosis of “Permanent Revolution”.

Internationalism

The 1905 Revolution demonstrated in practice the leading role of the working class. While the Liberals had run for cover, the workers set up Soviets, which Lenin recognised as the embryo of workers’ rule. The RSDLP grew enormously under these conditions and served to pull the two factions of the party closer together.

The defeat of the 1905 Revolution, however, was followed by a period of ruthless reaction. The party faced tremendous difficulties as it become more and more isolated from the masses. The Bolsheviks and Mensheviks grew further apart politically and organisationally, until in 1912 the Bolsheviks constituted themselves as a separate party.

In these years, Trotsky was a “conciliator” between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. He had stood apart from the two factions while preaching “unity”. This led to bitter clashes with Lenin, who had upheld Bolshevik political independence and these clashes were later used by the Stalinists to discredit Trotsky, despite Lenin’s wish, contained in his Testament, that Trotsky’s non-Bolshevik past must not be held against him.

The revival of the workers’ movement after 1912 witnessed growing support for the Bolsheviks, which claimed the support of the overwhelming majority of Russian workers. This growth, however, was cut across by the First World War.

The betrayal of August 1914 and the capitulation of the leaders of the Second International marked a terrible blow to international socialism. It meant the effective death of this International.

The small handful of internationalists worldwide regrouped at an anti-war Conference held in Zimmerwald in 1915, where Lenin called for the creation of a new workers’ International. These were very dark times – the forces of Marxism were now completely isolated. Revolutionary prospects looked very dim indeed. In January 1917, Lenin addressed a small meeting of the Swiss Young Socialists in Zurich. He remarked that the situation would eventually change but that he would not live to see the revolution. Yet, within the space of one month, the Russian working class would bring Tsarism crashing down and bring about a situation of dual power. Within nine months, Lenin would head a government of Peoples’ Commissars.

The Russian Revolution

When in Zurich, Lenin scoured the newspapers for the latest news from Russia. He saw that the soviets, now dominated by the leaders of the Social Revolutionaries (SRs) and the Mensheviks, had handed power to the Provisional Government, headed by the monarchist Prince Lvov. He immediately telegraphed Kamenev and Stalin, who were wavering: “No support for the Provincial government! No trust in Kerensky!”

When in Zurich, Lenin scoured the newspapers for the latest news from Russia. He saw that the soviets, now dominated by the leaders of the Social Revolutionaries (SRs) and the Mensheviks, had handed power to the Provisional Government, headed by the monarchist Prince Lvov. He immediately telegraphed Kamenev and Stalin, who were wavering: “No support for the Provincial government! No trust in Kerensky!”

Writing from exile, Lenin warned:

“Ours is a bourgeois revolution, therefore, the workers must support the bourgeoisie, say the Potresovs, Gvozdyovs and Chkheidzes, as Plekanov said yesterday.

“Ours is a bourgeois revolution, we Marxists say, therefore the workers must open the eyes of the people to the deception practised by the bourgeois politicians, teach them to put no faith in words, to depend entirely on their own strength, their own organisation, their own unity, and their own weapons… You must perform miracles of organisation, organisation of the proletariat and of the whole people, to prepare the way for your victory in the second stage of the revolution.”

In his Farewell Letter to the Swiss Workers, Lenin explained the key task: “make our revolution the prologue to the world socialist revolution.”

When Lenin returned to Russia on 3rd April 1917, he put forward his April Theses: a Second Russian Revolution must be a step to the world socialist revolution! He came out against the old guard who were lagging behind the situation and fought to rearm the Bolshevik Party.

“The person who now speaks only of a ‘revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry’ is behind the times, consequently, he has in effect gone over to the petty bourgeoisie against the proletarian class struggle; that person should be consigned to the archive of ‘Bolshevik’ pre-revolutionary antiques (it may be called the archive of ‘old Bolsheviks’).”

He managed to win the support in the ranks and overcome the resistance of the leadership, which had ironically accused him of “Trotskyism”. In reality, Lenin had come over to Trotsky’s position of Permanent Revolution, but by his own route.

In May, Trotsky had returned to Russia after being interned by the British in Canada. “On the second or third day after I reached Petrograd I read Lenin’s April Theses. This was just what the revolution was in need of”, explained Trotsky. His line of thought is identical with Lenin’s. In agreement with Lenin, Trotsky joined the Inter-District Organisation with the aim of winning them over to Bolshevism. He entered into close collaboration with the Bolsheviks, describing himself everywhere as “We, Bolshevik-internationalists.”

The seizure of power

On 1st November 1917, at a meeting of the Petrograd committee, Lenin said that after Trotsky had become convinced of the impossibility of union with the Mensheviks, “there has been no better Bolshevik”. In reviewing the Revolution two years later, Lenin wrote: “At the moment when it seized power and created the Soviet republic, Bolshevism drew to itself all the best elements in the current of Socialist thought that were nearest to it.”

On 1st November 1917, at a meeting of the Petrograd committee, Lenin said that after Trotsky had become convinced of the impossibility of union with the Mensheviks, “there has been no better Bolshevik”. In reviewing the Revolution two years later, Lenin wrote: “At the moment when it seized power and created the Soviet republic, Bolshevism drew to itself all the best elements in the current of Socialist thought that were nearest to it.”

“Lenin did not come over to me, I went over to Lenin”, stated Trotsky modestly. “I joined him later than many others. But I make bold to think I understood him in a way not inferior to others.”

In the months preceding the revolution, Lenin had called on the Menshevik and SR-dominated Soviets to break with the capitalist ministers and take power, to which they stubbornly refused to do. However, the Bolshevik slogans – Bread! Land! Peace! All Power to the Soviets! – won rapid support amongst the masses. The mass demonstrations in June reflected this shift. It also prompted the new premier Kerensky to begin a campaign of repression against the Bolsheviks. The “July Days” saw the Bolsheviks driven underground. A campaign of hysteria was whipped up against them, calling them “German agents”, which forced Lenin and Zinoviev into hiding and the arrest of Trotsky, Kamenev, Kollontai and other Bolshevik leaders.

In August, General Kornilov tried to impose his own fascist dictatorship. Desperate for help, and fearing Kornilov, the government released Trotsky and other Bolsheviks. The Bolshevik workers and soldiers stepped into the breach and defeated Kornilov’s counter-revolution in the process.

This boosted support enormously for the Bolsheviks, who won majorities in both the Moscow and Petrograd Soviets. “We were the victors”, stated Trotsky concerning the elections at the Petrograd Soviet. This victory proved decisive, and became an essential stepping-stone to the victory in October.

Lenin, who by now was in hiding in Finland, became very impatient with the Bolshevik leaders. He feared that they were dragging their feet. “Events are prescribing our task so clearly for us that procrastination is becoming positively criminal”, explained Lenin in a letter to the Central Committee. “To wait would be a crime to the revolution.” In October, the Central Committee took the decision to take power, against the votes of Zinoviev and Kamenev, who issued a public statement opposing any insurrection and for the Party to look towards the convening of the Constituent Assembly!

Trotsky, as head of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, acted swiftly to ensure the smooth transfer of power on 25th October 1917. The Revolution succeeded in a bloodless fashion and on the following day, 26th October, its results were announced to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. This time, the Bolsheviks held some 390 delegates out of a total of 650 present, a clear majority. In protest, the Mensheviks and Right SRs walked out. Lenin, who addressed the Congress, simply proclaimed to the triumphal delegates: “We will proceed to construct the Socialist order.” The Congress then proceeded to set up a new Soviet government with Lenin at its head. Despised just four months earlier, the Bolsheviks were now hailed by the revolutionary workers.

In a matter of days, decrees were issued by Lenin’s government: on peace proposals and the abolition of secret diplomacy, on land to the toilers, on the right of nations to self-determination, on workers’ control and the right of recall over all representatives, on full equality of men and women, and on the complete separation of church from state.

When the Third Congress of Soviets in January 1918 proclaimed the establishment of the Russian Federated Soviet Republic, large tracts of Russia were still occupied by the Central Powers, bourgeois nationalists and White generals.

Five days after the Revolution, the new government was attacked by Cossack forces led by General Krasnov. The attack was repulsed and the general was handed over by his own men. However, he was released after giving his word not to take up arms. Of course, he broke his promise and went south to lead the Cossack White Army. Similarly, after the Winter Palace military cadets were released they staged an uprising.

Year One

The Revolution was all too generous and trusting in its early days. “We are accused of resorting to terrorism, but we have not resorted, and I hope will not resort, to the terrorism of the French revolutionaries who guillotined unarmed men”, stated Lenin in November. “I hope we shall not resort to it, because we have strength on our side. When we arrested anyone we told him we would let him go if he gave us a written promise not to engage in sabotage. Such written promises have been given.”

This innocence was recognised by Victor Serge, a former anarchist turned Bolshevik, who wrote in his book ‘Year One of the Russian Revolution’:

“The Whites massacre the workers in the Arsenal and the Kremlin: the Reds release their mortal enemy, General Krasnov, on parole… The revolution made the mistake of showing magnanimity to the leader of the Cossack attack. He should have been shot on the spot… [Instead] He was to go off to put the Don region to fire and the sword.”

No sooner had the Soviet power established itself than the imperialists acted to crush the revolution in blood. In March 1918 Lenin moved the government to Moscow as Petrograd had become vulnerable to German attack.

Soon afterwards, British troops landed in Murmansk accompanied by American and Canadian forces; the Japanese landed in Vladivostok alongside British and American battalions. The British also seized the port of Baku to get their hands on the oil. French, Greek and Polish forces landed in the Black Sea ports of Odessa and Sevastopol and linked up with the White armies. The Ukraine was occupied by the Germans. In all, 21 foreign armies of intervention on several fronts confronted the Soviet government forces. The Revolution was fighting for its life. It was surrounded, starving and infested with conspiracies.

White Terror

The SR party leadership endorsed the principle of foreign intervention to “restore democracy”. A similar counter-revolutionary position was held by the Mensheviks, which placed them in the enemy camp. They collaborated with the Whites and took money from the French government to carry out their activities.

In the summer of 1918 attempts were made to murder Lenin and Trotsky. On 30th August, Lenin was shot, but managed to survive. On the same day, Uritsky was assassinated, as was the German ambassador. Volodarsky was also killed. The plot to blow up Trotsky’s train was fortunately foiled. This White Terror served in turn to unleash the Red Terror in defence of the Revolution.

The White Terror was played down by the capitalists, who blamed everything on the Reds. White atrocities “were generally the work of individual White generals and warlords and were not systematic or matters of official policy”, explains Anthony Read, in an attempt to excuse them. “But they often matched and sometimes outdid the Red Terror.” In fact, as a policy they always outdid the Red Terror in terms of brutality, as is the nature of counter-revolutionary forces.

Interestingly, Read goes on to describe the methods of General Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg:

“No Bolshevik, for instance, could equal the White General Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, a German Balt born in Estonia, who was sent by the Provisional Government to the Russian far east, where he claimed to be a reincarnation of Genghis Khan and did his best to outdo the Mongol conqueror in brutality. A fanatical anti-Semite, in 1918 he declared his intention of exterminating all the Jews and commissars in Russia, a task he set about with great enthusiasm, having his men slaughter any Jew they came across in a variety of barbarous ways, including skinning them alive. He was also noted for leading his men in nocturnal terror rides dragging human torches across the steppe at full gallop, and for promising to ‘make an avenue of gallows that will stretch from Asia across to Europe’.”

This was the fate that awaited the workers and peasants of Russia in the event of a victory of the counter-revolution. It was the fate of Spartacus and his slave army at the merciless hands of the Roman slave-state. The alternative to Soviet power was no “democracy” but the most brutal bloodthirsty fascist barbarism. The whole effort of the Red Army and the Cheka, the security force, was therefore directed at winning the Civil War and defeating the counter-revolution.

The Soviet government had no alternative but to fight fire with fire, and to make a revolutionary appeal to the troops of foreign intervention. As Victor Serge explained:

“The toiling masses use terror against classes which are in a minority in society. It does no more than complete the work of newly arisen economic and political forces. When progressive measures have rallied millions of workers to the cause of revolution, the resistance of the privileged minorities is not difficult to break at this stage. White terror, on the other hand, is carried out by these privileged minorities against the labouring masses, whom it has to slaughter, to decimate. The Versaillais (name given to counter-revolutionary forces that put down the Paris Commune) accounted for more victims in a single week in Paris alone than the Cheka killed in three years over the whole of Russia.”

A period of “War Communism” was forced upon the Bolsheviks, where grain was forcibly requisitioned from the peasants to feed the workers and soldiers. Industry, ravaged by sabotage, war and now civil war, was in a state of complete collapse.

The imperialist blockade crippled the country. The population of Petrograd fell from 2,400,000 in 1917 to 574,000 in August 1920. Typhoid and cholera killed millions. Lenin described the situation as “Communism in a besieged fortress”.

On 24th August 1919, Lenin wrote: “industry is at a standstill. There is no food, no fuel, no industry.” Faced with this disaster, the Soviets relied upon the sacrifice, courage and will-power of the working class to save the revolution. In March 1920, Lenin declared “The determination of the working class, its inflexible adherence to the watchword ‘Death rather than surrender!’ is not only a historical factor, it is the decisive, the winning factor.”

Aftermath of the Civil War

Under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, who had organised the Red Army from scratch, the Soviets were victorious, but at a terrible cost. Deaths at the front, famine, disease, all combined with economic collapse.

By the end of the Civil War, the Bolshevik government was forced to make a retreat and introduce the New Economic Policy. This allowed the peasants a free market in their grain and contributed to the growth of strong capitalist tendencies, resulting in the emergence of the Nepmen and Kulaks. It was simply a breathing space.

Given the low cultural level, where 70% of the population were illiterate, the Soviet regime had to rest for support on the old Tsarist officers, officials and administrators, who were opposed to the revolution. “Scratch the soviet state at any point and underneath you will see the same old Tsarist state apparatus”, stated Lenin bluntly. With the continuing isolation of the revolution, this constituted a grave danger through a bureaucratic degeneration of the revolution. The working class was systematically weakened by the crisis. The Soviets simply ceased to function in this situation as the careerists and bureaucrats filled the vacuum.

Despite measures being introduced to combat this bureaucratic menace, the only real saviour of the revolution was the success of the world revolution as material assistance from the West.

In early 1919 Lenin had established the Third International as a weapon for spreading the revolution internationally. It was a school of Bolshevism. Mass Communist Parties were soon established in Germany, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia and other countries.

Unfortunately, the revolutionary wave following the First World War was defeated. The revolution in Germany in 1918 had been betrayed by the Social Democrats. The young Soviet Republics in Bavaria and Hungary had been crushed in blood by the counter-revolution. The revolutionary factory occupations in Italy in 1920 had also been defeated. Once again, in 1923, all eyes were on Germany which was in the grip of a revolutionary crisis. However, the false advice given by Zinoviev and Stalin resulted in its tragic defeat.

This came as an almighty blow to the morale of the Russian workers, who were hanging on by the skin of their teeth. At the same time, the defeat reinforced the growth of bureaucratic reaction in the state and the Party. With the incapacity of Lenin following a series of strokes, Stalin began to emerge as the figurehead of the bureaucracy. In fact, Lenin’s last struggle was in a bloc with Trotsky against bureaucracy and Stalin. Stalin retreated, but a final stroke left Lenin paralysed and speechless.

Prior to this, Lenin had drawn up a Testament. In it he states Stalin “having become General Secretary, [which Lenin opposed – RS] has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.” “Comrade Trotsky, on the other hand… is distinguished not only by outstanding ability. He is personally perhaps the most capable man of the present CC…” He warned there was a danger of a split in the Party.

Stalinism

Two weeks later, Lenin added an addendum to his Testament after Stalin swore at and abused Krupskaya for helping Trotsky and others communicate with Lenin. Lenin broke off all personal relations with Stalin. “Stalin is too rude and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst and in dealings among us communists, becomes intolerable in a General Secretary”, stated Lenin. He urged that Stalin be removed from his position due to his disloyalty and tendency to abuse power.

But on 7th March 1923, Lenin suffered a stroke that rendered him completely incapacitated. He would remain in this state until his death on 21st January 1924. Lenin’s removal from political life gave increased power to Stalin, which he used to full advantage, not least in suppressing Lenin’s Testament.

It was left to Trotsky to defend Lenin’s heritage, which was being betrayed by Stalin. The victory of Stalinism was due fundamentally to objective reasons, above all the terrible economic and social backwardness of Russia and its isolation.

The subsequent defeat of the international revolution in Britain and especially China, served to further demoralise the Russian workers, exhausted by years of struggle. On the basis of this terrible weariness, the bureaucracy, headed by Stalin, consolidated its stranglehold. Lenin’s body, against the protests of his widow, was then placed in a mausoleum.

It is a monstrous lie to suggest that Stalinism is the continuation of the democratic regime of Lenin, as the apologists of capitalism claim. In reality, a river of blood separates the two. Lenin was the initiator of the October Revolution; Stalin was its grave-digger. They had nothing in common.

We end this tribute with the fitting words of Rosa Luxemburg:

“Whatever a party could offer of courage, revolutionary far-sightedness and consistency in a historic hour, Lenin, Trotsky and the other comrades have given in good measure. All the revolutionary honour and capacity which Western social democracy lacked was represented by the Bolsheviks. Their October uprising was not only the actual salvation of the Russian Revolution; it was also the salvation of the honour of international socialism.”

In this centenary year of the Russian Revolution, we pay homage to this great man, his ideas and courage. Lenin combined theory with action and personified the October Revolution. Lenin and the Bolsheviks changed the world; our task at this time of capitalist crisis is to finish the job.