27 July this year marks the 70th anniversary of the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement, which halted the three-year-long, all-out conflict known as the Korean War.

The Armistice is not a peace agreement. Technically, the two states that exist on the Korean Peninsula to the north and south of the 38th parallel are still at war with each other.

In the West, some have called the Korean War the ‘Forgotten War’. It is true that, in the days since the cessation of conflict in Korea, there has been no shortage of bloody wars offered to humanity by capitalism. But the Korean War holds historic significance that cannot be neglected.

It showed that a system of a nationalised planned economy could withstand the assault of US imperialism. It contained flashpoints of workers’ power – the first instances in East Asia.

Yet the fact was that the working class did not emerge as an independent force, with a clear programme, capable of seizing the lead in the struggle that unfolded.

As a result, the conflict turned into a bloody conventional war, and US imperialism was able to remain on the Peninsula as part of a criminal compromise with Stalinism – thus tearing apart a nation that had hitherto been unified for over 500 years.

End of WWII and the 38th Parallel

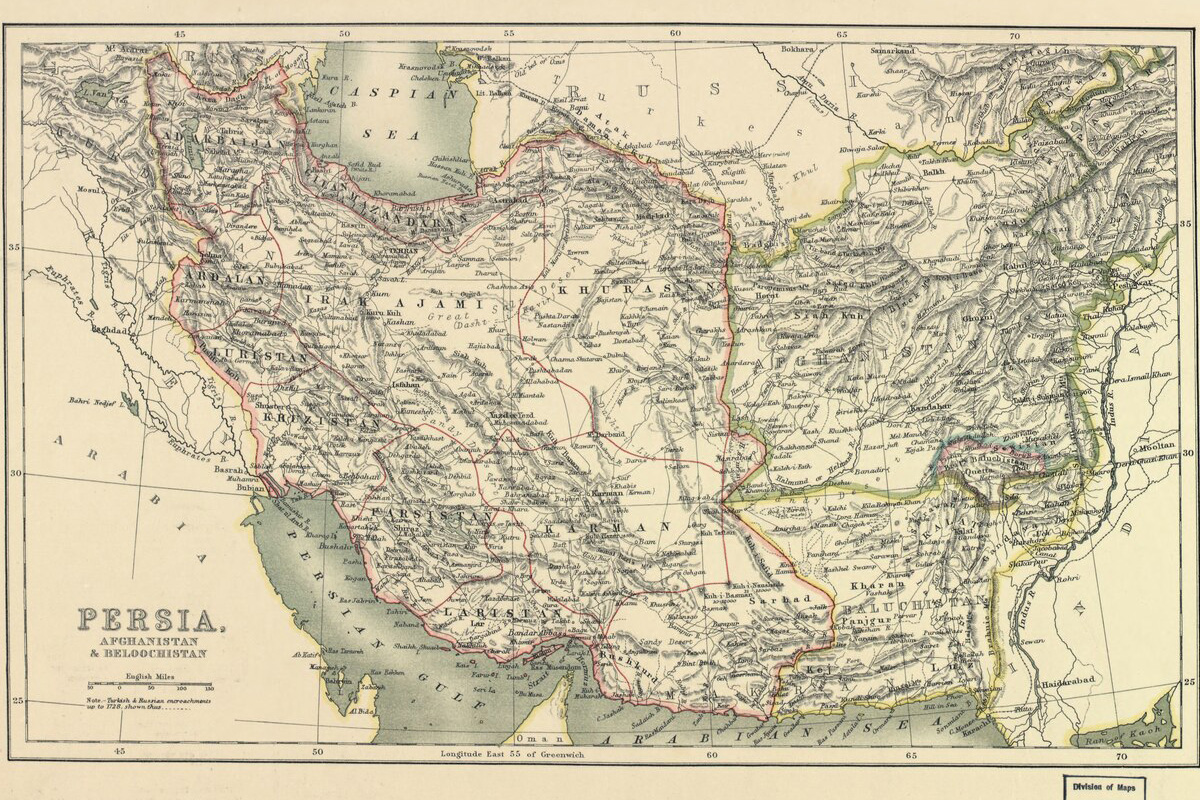

For much of its history, Korea existed as an independent kingdom, sandwiched between China and Japan.

In the 19th century, Korea under the Joseon dynasty gradually fell under the domination of Japanese imperialism as the Chinese empire waned.

By August 1910, the entirety of Korea was formally annexed by the Japanese Empire – an important step in the ambitious young imperialist power’s thrust towards further domination of all of Asia.

But when the tide of the Second World War turned against the Axis countries, of which Japan was a part, the two primary forces amongst the Allies, the US and the Soviet Union under Stalin, began to manoeuvre against one another, in preparation for the post-war period.

When the writing was on the wall for Japan, the US began to plot to ensure Stalin could not expand his sphere of influence in the post-war world.

In the East, the US dropped atom bombs on Japan – first in Hiroshima, and then in Nagasaki – as a brutal and unnecessary show of force aimed at the Soviets.

Tens and thousands of innocent lives were extinguished in Japan by American weapons of mass destruction – including at least 10,000 Korean forced labourers living there at the time. This act was perpetrated even though the Japanese state was clearly leaning towards surrender.

The Soviet bureaucracy also hoped to expand its sphere of influence, in order to establish a buffer against the US, and to protect its own interests.

In the East, Stalin quickly declared war on Japan in 1945. The Red Army then swept through Mongolia, north-eastern China, and eventually the north of Korea, with little resistance from the local Japanese forces, halting at the 38th parallel on the Korean peninsula, in order for the US to land in the south of Korea and take hold there.

According to Bruce Cumings, the use of the 38th parallel as the dividing line between Soviet and American occupation zones in Korea was a hasty decision on the part of the US. Two young American colonels were given thirty minutes to draw this line. Stalin agreed to this decision, and at no point was any Korean given a say in the matter.

This was a criminal concession that Stalin agreed with US imperialism. Had the Red Army continued its advance into the whole of Korea, and encouraged the masses there to take power and prevent the US from even landing, the tide of world revolution would have been enormously strengthened.

People’s Committees

In the tenuous period when all the major forces at play were advancing into positions, while Japan’s hold over the Korean Peninsula was rapidly collapsing, there existed, for a time, a vacuum of state power. In this vacuum, the Korean peasants and workers took it upon themselves to take power into their own hands locally, and to run their affairs for themselves.

This effort was known as the People’s Committees (인민위원회), as village peasants and workers throughout Korea organised themselves into councils. These local committees linked up in turn into larger, regional bodies.

The villagers and workers would elect their own committees as the new authorities for their local governments, and many of them attempted to conduct their own land and social reforms, which smashed against not only the old Japanese authorities, but also traditional Korean landlords.

The rapid formation of the People’s Committees was so formidable that they could not be immediately stopped by the Soviets or the US occupation forces.

Within them, there were various political tendencies, reflecting the balance of class and ideological forces in any given region.

This phenomenon is, from a Marxist perspective, extremely significant. The People’s Committees, especially those made up of urban workers, could have become the basis of working-class rule – in much the same way as the soviets emerged throughout Russia in the 1905 and 1917 revolutions.

Under a Marxist leadership, in Russia, these soviets became the basis for a new workers’ state after the success of the October Revolution of 1917.

In the absence of a Marxist leadership to unify them into a force capable of taking power, the People’s Committee’s were eventually captured or crushed by forces operating in the North and the South. Still, their existence was a significant factor that influenced how the Korean War would eventually unfold.

Northern and Southern states

As the Soviets halted their forces north of the 38th parallel, the US occupation forces were allowed to consolidate their positions in the south.

The US, seeking to curb the Soviet Union, quickly gathered the support of the most reactionary bourgeois and landlord elements in the south. They also helped reorganise the old police force, in conjunction with virulently anti-communist elements, into a new, brutal police force: the Korean National Police (KNP).

The KNP would viciously crack down on communists and People’s Committees operating in the South. A similar reorganisation took place in the military. The US even brought in officers from the former Japanese army to train them.

This new, reactionary armed body of men would be the basis of the future state known as the Republic of Korea, to be headed by the most corrupt and autocratic bourgeois elements like Syngman Rhee.

In the north, the situation was different. Stalin, with his narrow nationalist outlook, was only interested in creating a satellite regime under the USSR’s direction. But this proved to be a much more complicated endeavour for him.

Stalin’s preference, as in many countries in Eastern Europe, would have been to simply lean on a well-established local Communist Party – that had undergone bureaucratic degeneration – as a direct local agent. But no such thing existed in Korea by the end of WWII.

At that time, the Korean communists were scattered. Some were indeed directly tied to and controlled by the USSR. Many others had long fought alongside the Chinese Communist Party, since the Yenan period in the 1930s, and were thus deeply tied to Mao Zedong’s leadership. And Mao, by that time, had gained his own mass base in China, independent of Moscow.

Still others came from partisan militias that operated across northern Korea and northeast China, and which had a degree of independence from both the USSR and the CCP. And there were others that came from underground cells that worked in the south and Jeju Island under Japanese colonialism.

If the policies of the Soviet Union and China had been guided by genuine Bolshevik methods and ideas, then these divisions would not have mattered. They would have simply made a joint call for the formation of a fraternal federation between China, Korea, and the Soviet states, as part of a future world federation of socialist republics.

Instead, the fundamentally nationalist calculations of the bureaucracies of both the USSR and China, and also the Korean Stalinists of various stripes, ended with a complex compromise, aimed at forming a state that would fit the interest of both the USSR and China.

In the North, the USSR directed the merger of some of these forces into a Workers’ Party of North Korea. Moscow quickly intervened in and bureaucratised the People’s Committees in the north, under this party’s leadership.

It was also at this time that Kim Il-Sung, a guerrilla partisan leader, was agreed upon as a suitable compromise leader to balance between the pro-Moscow and pro-CCP tendencies.

On this basis, a new state in the north was formed. A new government – modelled after the bureaucratic, one-party, totalitarian regime in the Soviet Union, and based on a nationalised planned economy – came into being, but under the leadership of Kim Il-Sung.

Kim developed a certain independence with his own base, by appealing to nationalist and anti-imperialist sentiment. As an individual, his personal determination to unite the peninsula would play an important role in how the war unfolded.

Uprisings

For a time, the northern regime, and the Russians, allowed the People’s Committees to carry out land expropriations on their own accord. The People’s Committees in the south, on the other hand, were attacked by the southern police force and reactionary right-wing gangs.

This made many among the southern masses anxious. For them, it was clear that the process in the north represented genuine progress. Unable to carry the same tasks through to fruition, the masses became increasingly frustrated. This in turn led to even more explosive armed uprisings against the US-backed authorities in the south.

A particular flashpoint was in Jeju Island. Being geographically detached from the mainland peninsula, but with a no less proud history of rebellions and uprisings, the Jeju People’s Committees – in close coordination with the underground trade unions there and the Workers’ Party of South Korea – staged a general strike on 10 March 1947, aimed at repelling attacks from right-wing gangs dispatched by the South Korean regime.

The southern troops in Jeju Island, commanded by US officers, enforced a brutal crackdown on this uprising, resulting in upwards of 30,000 deaths. Although crushed in the end, the revolt at Jeju Island in turn inspired more rebellions across the US-dominated South Korea.

Witnessing this process from the north, Kim Il-Sung decided that the time was right to expand the deformed workers’ state under his leadership across the whole of Korea.

At the same time, Syngman Rhee in the south held the same ambition: wishing to destroy the new social system in the north, and to unify Korea as a capitalist dictatorship with himself at its head.

This was a social war between capitalism and planned economies. After the Chinese revolution of 1949, with communist insurgencies ongoing in Malaysia and Vietnam, Eisenhower expressed the concern of US imperialism that Korea would be the first in a series of ‘dominos’ to fall in the region. Thus the seeds of conflict were present from the very beginning.

‘Peacekeeping’ and US intervention

After gaining reluctant approval from Stalin and Mao, Kim Il-Sung made his move.

On Sunday 25 June 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) of the north marched into the south, captured Seoul, and drove further southward without meeting meaningful resistance.

The massive success of the KPA’s advance can be explained by the revolutionary measures they took. Everywhere they went, the southern People’s Committees were restored, and peasants would redistribute the land. The Seoul People’s Committee expropriated all Japanese property, and that belonging to the South Korean capitalists.

These measures won enthusiastic support from the masses. Many people joined the rebels, who had been carrying on guerrilla operations in the south even before the northern army arrived. On this basis, the northern forces rapidly drove towards Busan, the southern port city.

The existing US and southern forces faltered against this powerful, revolutionary advance, until they were able to hold off KPA advances around Busan with the aid of a hastily deployed Task Force Smith from Japan.

With the authority of the phoney ‘United Nations Peacekeeping Mission’, the US under Marshal Douglas McArthur organised a forceful invasion into Incheon, then eventually drove north to take Seoul, and in turn Pyongyang, the north’s capital.

On the basis of sheer military might and aerial bombardment, the US’ direct intervention militarily pushed back the KPA, and even threatened to take over all of the north.

China’s involvement and social war

As the US forces drove into North Korea, the Chinese under Mao watched with anxiety. For them, the defeat of the Korean regime would bring US forces close to their borders in the northeast. This threatened the newly-founded state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The Mao regime realised that an American-dominated Korean Peninsula would pose an existential threat to the newly founded PRC. Thus, China was compelled to send troops to Korea to repel the US-backed counter-attack, which would mark a decisive turning point for the war.

In October 1950, China sent an initial 260,000 troops into Korea, pushing the Americans back down towards the south.

In the end, therefore, the intervention of the imperialists turned Korea into hell on Earth, dragging out into a multi-year long conflict involving British, Canadian, Australian, Ethiopian, and many other nations’ soldiers; claiming the lives of thousands on both sides, along with millions of civilians.

In the bloody process, Seoul changed hands four times. And the conflict ultimately centred above and below the 38th parallel.

As the war came to an exhausted stalemate, a split between Douglas MacArthur and President Truman opened over strategic questions. At one point, Truman and MacArthur both considered using nuclear weapons against North Korea and China.

The split centred on whether Washington or the military had the power to authorise such a strike. The conflict between the two became public and acrimonious. Finally, in April 1951, the so-called ‘war hero’ MacArthur would be relieved of his command, to be replaced by Lt. General Matthew. B. Ridgeway.

The removal of MacArthur did not stop the war, which dragged out for a few more years, until the two sides finally agreed to a ceasefire in 1953, with the 38th parallel as the de facto border between the North and the South.

A so-called ‘Demilitarized Zone (DMZ)’ was set up in the strip of land between the north and south, which to this day remains the most militarised area in the world.

Division cemented

The Korean War ended in a draw, and left a significant impact on the course of world history. Internationally, it showed for the first time that US imperialism, with all its superior military might, could not easily defeat the forces conjured by a new social system based on a nationalised planned economy.

The fighting was brutal. Upwards of four million lives were lost, at least half of whom were civilians. To put this in perspective, that represented a number similar to the entire population of Ireland at the time.

It would be false to apportion equal blame for civilian deaths however. According to South Korea’s own investigation conducted in 2005, over 82 percent of massacres of civilians were conducted by South Korean forces under the command of the US. The American air force also dropped over 635,000 tons of bombs on North Korea – more than in the entire Pacific theatre throughout WWII.

In one incident, hundreds of thousands of Koreans were drafted into a National Defense Corps by the US-backed government in the South. But when the Chinese were advancing down the peninsula, the draftees were forcibly marched south by their officers to evade capture.

The officers, however, had embezzled money intended for purchasing food, and therefore 300,000 members of the National Defense Corps were lost through death or desertion. 90,000 deaths were directly attributed to starvation or disease on the ‘death march’ and in training camps.

Despite all this inhumanity, the fact that the war ended in a stalemate shows the strength of the nationalised planned economies of China and the USSR, and the weakness of US imperialism – especially when faced with holding a people who refuse to remain under the jackboot of imperialism.

Ted Grant summarised the significance of the war thusly:

“Korea, divided into Russian and American spheres of influence, reveals the weakness of imperialism in the whole of the Far East. Without the direct intervention of American imperialism the Korean Chiang Kai Shek would have collapsed as ignominiously as the Chiang regime itself. At best American imperialism will be enabled to retain a foothold after a lengthy struggle, and American forces will be pinned down like those of the French in Indo-China and the British in Malaya, even in the event of a complete victory in the South. This is the measure of the decay of the old relations of capitalism and imperialism of the past. Capitalism rots at its weakest point.”

Thus, the tragic division of the Korean nation was crystallised at the end of the war. The north under Kim Il-sung consolidated into the so-called ‘Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’, where any element of workers’ and peasants’ power was snuffed out.

Instead, an autocratic, bureaucratic state came into being – one that bastardised the ideas of socialism so much that they even justified the rule of a hereditary dynasty. The Kim bureaucracy also seals off the country, rather than seeing itself as a motivator for further international revolution.

The south, contrary to popular belief, by no means emerged as some ‘bastion of democracy’. Prior to the 1990s, the South Korean masses were ruled over by no-less brutal military dictators backed by the US.

US imperialism continued to be responsible for heinous crimes against the masses in the South, including the crushing of the Gwangju commune of 1980.

Through the sacrifice of countless lives of workers and youth, the South was forced to allow for certain bourgeois democratic freedoms, whilst keeping many repressive features of the military dictatorship of the past intact.

The legacy of the Korean War – of the crimes of imperialism and the betrayals of Stalinism – can be felt down to the present day.

For further reading on the trajectories of the states in the north and south of the peninsula following the war, we recommend to our readers the following articles from the archives of marxist.com: