The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Similarly to the rise of Hitler and Stalin in the past, the emergence today of reactionary figures like Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen – the ‘not-so-Great’ individuals of history – might also seem to many like a horrific accident. Indeed, there are many superficial mainstream commentators today who frequently ascribe Trump and Le Pen’s success to their demagoguery, rhetorical skills, and forceful personality.

But when similar accidental events are occurring in one country after another, it is clearly a reflection of a wider process of political polarisation and fragmentation going on within society: a collapse of the liberal centre ground and a breaking down of the old status quo.

By contrast, two of the most popular political figures in the world right now are those who represent new mass movements on the Left: Jeremy Corbyn in the UK and Bernie Sanders in the USA. In this respect, the rapid – and entirely unexpected – rise of Corbyn and Sanders represents the other side of the coin to the vote for Brexit or the election of Donald Trump as US President.

And yet, ironically, neither of these left-wing leaders could by any means be considered new or fresh. Nor are either of them particularly ‘charismatic’ by any account. So why only now – after decades of tireless campaigning on the Left – are they both suddenly a point of reference for millions of workers and youth in Britain and America respectively?

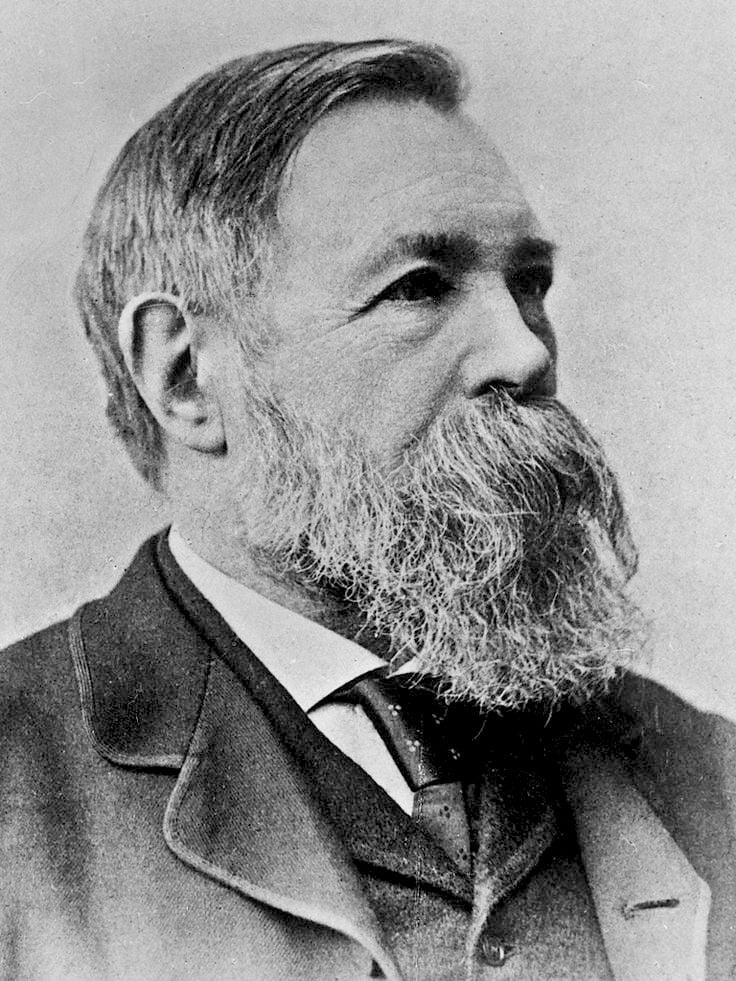

In both cases, they are clearly riding the wave of history – a wave of mass anger against the crooked Establishment and their rotten system. This fact again demonstrates Engels’ earlier assertion, which is worth repeating again here:

“That such and such a man and precisely that man arises at that particular time in that given country is of course pure accident. But cut him out and there will be a demand for a substitute, and this substitute will be found, good or bad, but in the long run he will be found.

This statement, however, does not deny the vital role that Corbyn, for example, now plays on the Left in Britain. At certain points in history, the hopes and dreams of a movement can become embodied and personified in one person. The relationship between Corbyn and the movement around is such an example of this phenomena.

Corbyn’s personal attributes – ‘principled’ and ‘honest’ are among the positive qualities most frequently ascribed to the Labour leader – reflect the craving amongst ordinary people for a leader who (and a party that) breaks with the Blairite mould of superficiality and fickleness so commonly associated with traditional politicians. In this respect, for many, the idea of a Corbyn movement without Corbyn seems impossible to imagine.

The same was true – and even more so – in the case of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, who came to embody and represent all the desires and aspirations of the masses. The result was a dialectical relationship between himself and the revolutionary Bolivarian movement: the more the masses pushed Chavez forward, the more confidence it gave him in the movement’s power, and the more this – in turn – inspired and radicalised the masses.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks

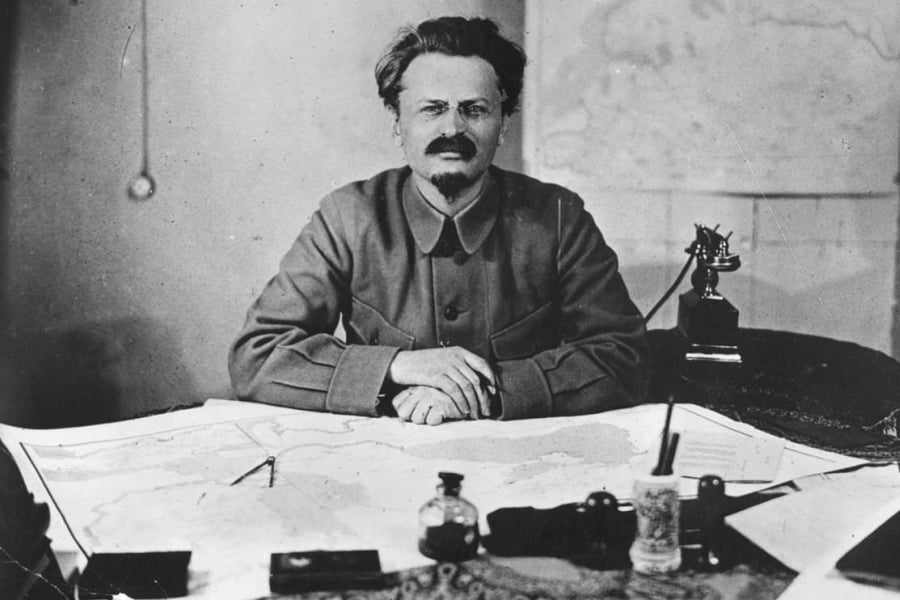

Similar was the relationship between Lenin, the Bolsheviks, and the Russian workers and peasants. “The ability to think and feel for and with the masses,” Trotsky stated in his Diary in Exile, “was characteristic of him [Lenin] to the highest degree, especially at the great political turning points.

Similar was the relationship between Lenin, the Bolsheviks, and the Russian workers and peasants. “The ability to think and feel for and with the masses,” Trotsky stated in his Diary in Exile, “was characteristic of him [Lenin] to the highest degree, especially at the great political turning points.

John Reed, the American journalist and socialist, noted in his brilliant first-hand account of the Russian Revolution – Ten Days That Shook the World – that Lenin was a remarkable leader: someone who was enormously admired and respected not because of his charisma, but amazingly in spite of his complete lack of charisma; and ultimately because of the clarity and correctness of the ideas that he put forward.

Lenin, Reed wrote, was:

“Unimpressive, to be the idol of a mob, loved and revered as perhaps few leaders in history have been. A strange popular leader – a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies – but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analysing a concrete situation. And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.”

Without Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917, the Bolsheviks would not have been armed with the necessary political ideas, perspectives, and demands to conquer the minds of the masses. But Lenin’s ‘greatness’ was itself the embodiment of all the historical lessons learnt by the Bolsheviks over decades of building a revolutionary organisation. Lenin was not born Lenin; he made himself.

Just as Lenin helped to forge the Bolshevik Party into the revolutionary weapon needed by the Russian workers and peasants, so too did the Party help to forge Lenin into the leader that was vitally required in the decisive moments of 1917.

Trotsky emphasises this point in a brilliant passage from his biography of Stalin, where he discusses Lenin’s return to Russia in 1917 and the question of his ‘April Theses’, which helped to politically re-orientate and re-arm the Bolsheviks for the revolutionary tasks at hand. In doing so, Trotsky explains the dialectical relationship that existed between Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, comparing the revolutionary guidance and leadership provided by Lenin to the scientific achievements of individual ‘geniuses’ like Charles Darwin and Isaac Newton:

“Every time that the Bolshevik leaders had to act without Lenin they fell into error, usually inclining to the Right. Then Lenin would appear like a deus ex machina and indicate the right road. Does it mean then that in the Bolshevik Party Lenin was everything and all the others nothing? Such a conclusion, which is rather widespread in democratic circles, is extremely biased and hence false.

“The same thing might be said about science. Mechanics without Newton and biology without Darwin seemed to amount to nothing for many years. This is both true and false. It took the work of thousands of rank and file scientists to gather the facts, to group them, to pose the problem and to prepare the ground for the comprehensive solutions of a Newton or a Darwin. That solution in turn affected the work of new thousands of rank and file investigators. Geniuses do not create science out of themselves; they merely accelerate the process of collective thinking.

“The Bolshevik Party had a leader of genius. That was no accident. A revolutionist of Lenin’s makeup and breadth could be the leader only of the most fearless party, capable of carrying its thoughts and actions to their logical conclusion. But genius in itself is the rarest of exceptions. A leader of genius orients himself faster, estimates the situation more thoroughly, sees further than others.

“It was unavoidable that a great gap should develop between the leader of genius and his closest collaborators. It may even be conceded that to a certain extent the very power of Lenin’s vision acted as a brake on the development of self-reliance among his collaborators.

“Nevertheless, that does not mean that Lenin was ‘everything’ and that the Party without Lenin was nothing. Without the Party Lenin would have been as helpless as Newton and Darwin without collective scientific work. It is consequently not a question of the special sins of Bolshevism, conditioned presumably by centralisation, discipline and the like, but a question of the problem of genius within the historical process. Writers who attempt to disparage Bolshevism on the grounds that the Bolshevik Party had the good luck to have a leader of genius merely confess their own mental vulgarity.

“The Bolshevik leadership would have found the right line of action without Lenin, but slowly, at the price of friction and internal struggles. The class conflicts would have continued to condemn and reject the meaningless slogans of the Bolshevik Old Guard…

“However, that does not mean that the right path would have been found anyway. The factor of time plays a decisive role in politics—especially, in a revolution. The class struggle will hardly bide its time indefinitely until the political leaders discover the right thing to do. The leader of genius is important because, in shortening the learning period by means of object lessons, he enables the party to influence the development of events at the proper moment.

“Had Lenin failed to come at the beginning of April, no doubt the Party would have groped its way eventually to the course propounded in his ‘Theses’. But could anyone else have prepared the Party in time for the October denouement? That question cannot be answered categorically.

“One thing is certain: in this situation—which called for resolute confrontation of the sluggish Party machine with masses and ideas in motion—Stalin could not have acted with the necessary creative initiative and would have been a brake rather than a propeller. His power began only after it became possible to harness the masses with the aid of the machine.” (Leon Trotsky, Stalin, chapter VII)

The Bolsheviks’ programme and traditions, in turn, however, were themselves the product of not just decades but centuries of lessons – lessons obtained from the entire generalised experiences of the class struggle, as contained within the pages of the wealth of theoretical material written by Marx, Engels, Plekhanov, and other leading proponents and defenders of the ideas of scientific socialism.

This highlights why, for Marxists, the question of theory and education is so vital in the building of a revolutionary organisation. Without such education, the lessons of previous generations will be lost forever to the ether.

Only by steeling ourselves in the ideas of Marxism can we ensure that each and every movement does not have to learn the lessons of history again for itself anew. Instead, we can pass the necessary conclusions on from one generation to the next, applying these important lessons to the concrete conditions of today, and providing an ‘unbroken thread’ to the struggle for socialism.

The motor force of history

Marxists are not fatalists who deny the role of human agency in events. Indeed, we are actively trying to build the revolutionary organisation that is necessary to transform society. Nor, however, do we agree with the postmodernists in their rejection of any general laws and dynamics within society. History is not “just one damn thing after another”.

Marxists are not fatalists who deny the role of human agency in events. Indeed, we are actively trying to build the revolutionary organisation that is necessary to transform society. Nor, however, do we agree with the postmodernists in their rejection of any general laws and dynamics within society. History is not “just one damn thing after another”.

Historical processes are, of course, complex. But that is not to say they are completely unpredictable or uncontrollable. Amidst the seemingly chaotic uncertainty of events, there is a degree of order. History has its own laws and dynamics, albeit only at a very general level.

Indeed, as discussed earlier, Trotsky notes in his History of the Russian Revolution how similar characters appear in similar situations throughout history, comparing the decrepit monarchies overthrown in the English, French, and Russian revolutions.

In turn, Trotsky explained, these revolutions themselves contained similar events and displayed similar processes, arising from the way in which mass consciousness changes and the class struggle expresses itself. For example, elsewhere, the same writer drew an analogy between the degeneration of the French Revolution into Bonapartism and the degeneration of the Russian Revolution into Stalinism, as the force of the masses withdrew from the scene of history in both cases.

The most general law asserted by the materialist view of history is that of the development of the productive forces: the fact that there is a tendency – in the long view – for humankind to increase our mastery over nature and our standards of living, as expressed in terms of society’s level of science, industry, technology, and technique. Simply put: today is generally better than yesterday, and tomorrow will be better than today.

When a society’s economic system and property relations become a barrier in the way of this development, Marx explained, “then begins the era of social revolution”.

But history does not wait – ordinary people cannot wait – for the revolutionary party or leader to arrive to carry through the social transformation that is required. At certain points, the objective conditions of poverty and destitution felt by the masses demand dramatic change in the here and now, regardless of what party or leadership is currently available.

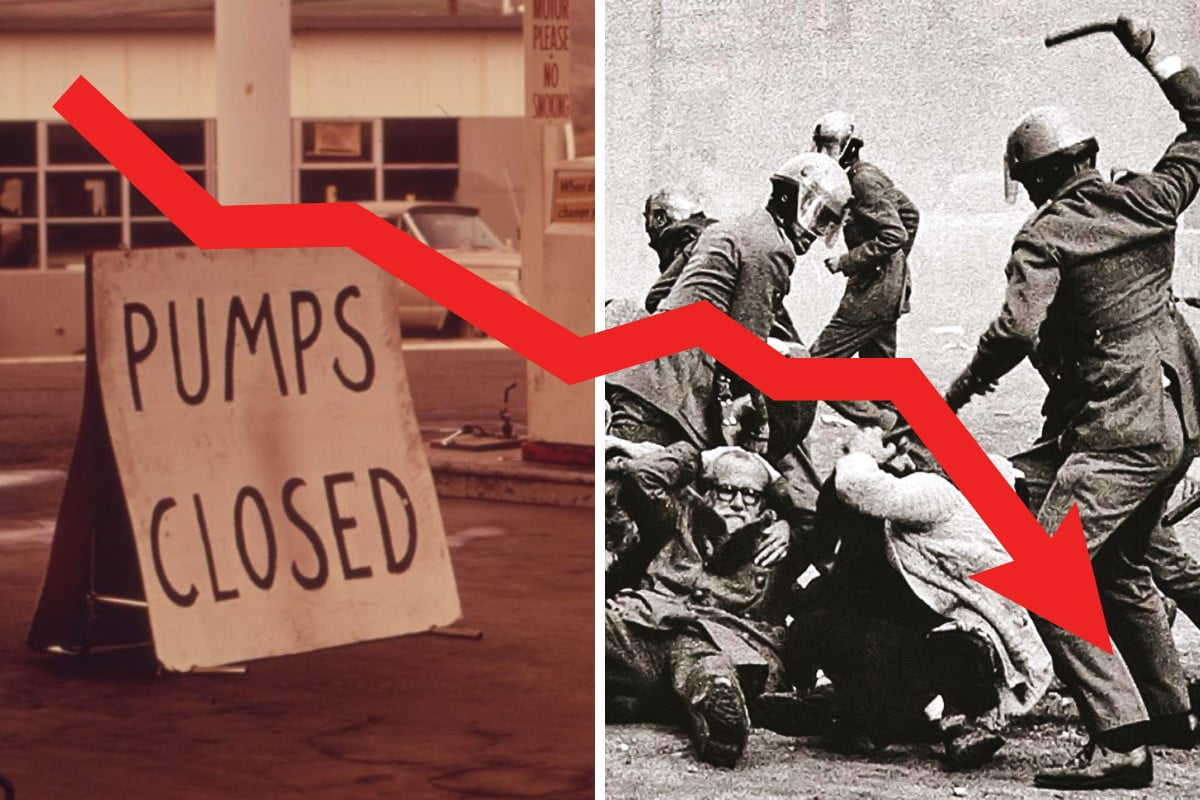

In the absence of the necessary ‘subjective factor’ of a revolutionary party, however, this process can occur with all manner of distortions. The evidence for this is the emergence of the various ‘deformed workers’ states’ seen throughout history: the Stalinist-style regimes – with a bureaucratic caste presiding over a nationalised, planned economy – that took power in many ex-colonial countries in the post-war period on the back of revolutionary movements against imperialism and landlordism.

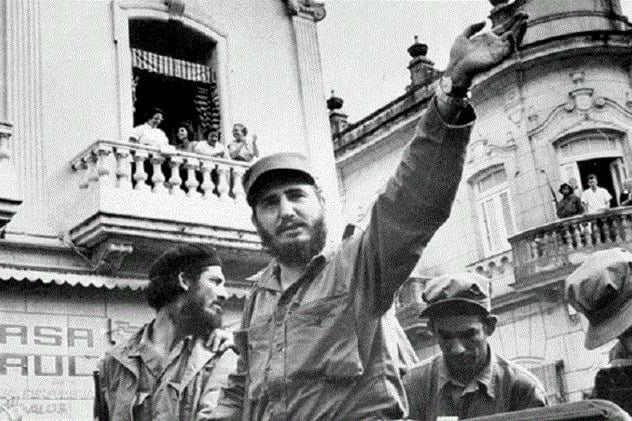

From the 1949 Chinese and 1959 Cuban revolutions, to the Baathist and Mengistu regimes in Syria and Ethiopia respectively: all of these examples, and many more, Ted Grant explained in a seminal article on the Colonial Revolutions and the Deformed Workers’ States were a product of the objective necessity for revolution in these countries – a rebellion of the masses against the existing social relations and contradictions left behind from decades and centuries of imperialism and colonialism.

“Under the conditions of the decay of capitalism-landlordism in the colonial countries, all the social contradictions are aggravated to an extreme. Social tensions reach an unbearable level. Hence in one country after another in Asia, Africa and Latin America, bourgeois democracy is replaced by bourgeois Bonapartist dictatorships or proletarian Bonapartist dictatorships. In the above-named ex-colonial countries not one proceeded on the model of the norm of the socialist revolution.”

Elsewhere, in Egypt in the 1950s, military-figure-turned-president Gamal Abdel Nasser ended up nationalising important key sectors of the economy, such as the Suez Canal.

Similarly in all cases, petit-bourgeois leaders left nationalists like Mao and Castro were pushed much further in terms of their economic programme than they had ever originally intended, due to the objective conditions that they faced. Attempting at first just to carry out basic economic reforms and demands for sovereignty, these leaders were forced to shift far to the left as a result of the pressure of the masses from below, and the counter-pressures of imperialism and the local comprador capitalists.

Ultimately, as Ted Grant emphasised, the role of such leaders in the colonial revolutions had little to do with their personal beliefs or individual attributes, and everything to do with the motor force of historical necessity and societal change that they came to embody and represent:

“It is important to see that what all these variegated forces have in common is not the secondary personal differences but the social forces and class forces they represent.

“Mengistu, Castro, [etc.]…broke with their class background and the advantages or disadvantages of their bourgeois and university education and outlook. It is true that they did not put themselves on the standpoint of the proletariat – as Marx and Lenin did – but they accepted the much easier ‘socialism’ which entailed the individual rule of them and of their elite on the backs of the working class and peasants.

“All individual differences are stamped out by the decisive class and economic changes which they have presided over in their countries and their societies.”

Freedom and necessity

Marxism, therefore, does not place the importance of historical conditions and of the individual in a mutually exclusive manner to one another. Rather, these factors – of the ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’; of ‘necessity’ and ‘accident’ – exist as a unity of opposites.

Marxism, therefore, does not place the importance of historical conditions and of the individual in a mutually exclusive manner to one another. Rather, these factors – of the ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’; of ‘necessity’ and ‘accident’ – exist as a unity of opposites.

It is clear that we neither possess ‘free will’, in the sense of an unconstrained ability to determine our own future; nor are we subject to the fatalistic forces of ‘destiny’.

Ultimately, as Engels commented, referencing Hegel, real freedom “does not consist in any dreamt-of independence from natural laws, but in the knowledge of these laws, and in the possibility this gives of systematically making them work towards definite ends.”

“This holds good in relation both to the laws of external nature and to those which govern the bodily and mental existence of men themselves – two classes of laws which we can separate from each other at most only in thought but not in reality.” (Engels, Anti-Dühring, chapter XI)

Even the greatest individual, for example, cannot conjure up magical powers to defy gravity and fly. But through the development of science we can, over time, learn to understand the laws of gravity and motion in order to invent machines – such as aeroplanes – that can overcome the forces of nature and allow us to fly.

So it is too in terms of the relationship between the individual and history. No historical figure can prevail in the face of powerful social forces acting against them. Without the necessary material conditions, even the most intelligent, charismatic, and determined leader can only go so far.

Engels remarked as such in relation to the Utopian Socialists: the political predecessors to himself and Marx, who idealistically believed that all that was needed in order to bring about socialism was “the individual man of genius, who has now arisen and who understands the truth.”

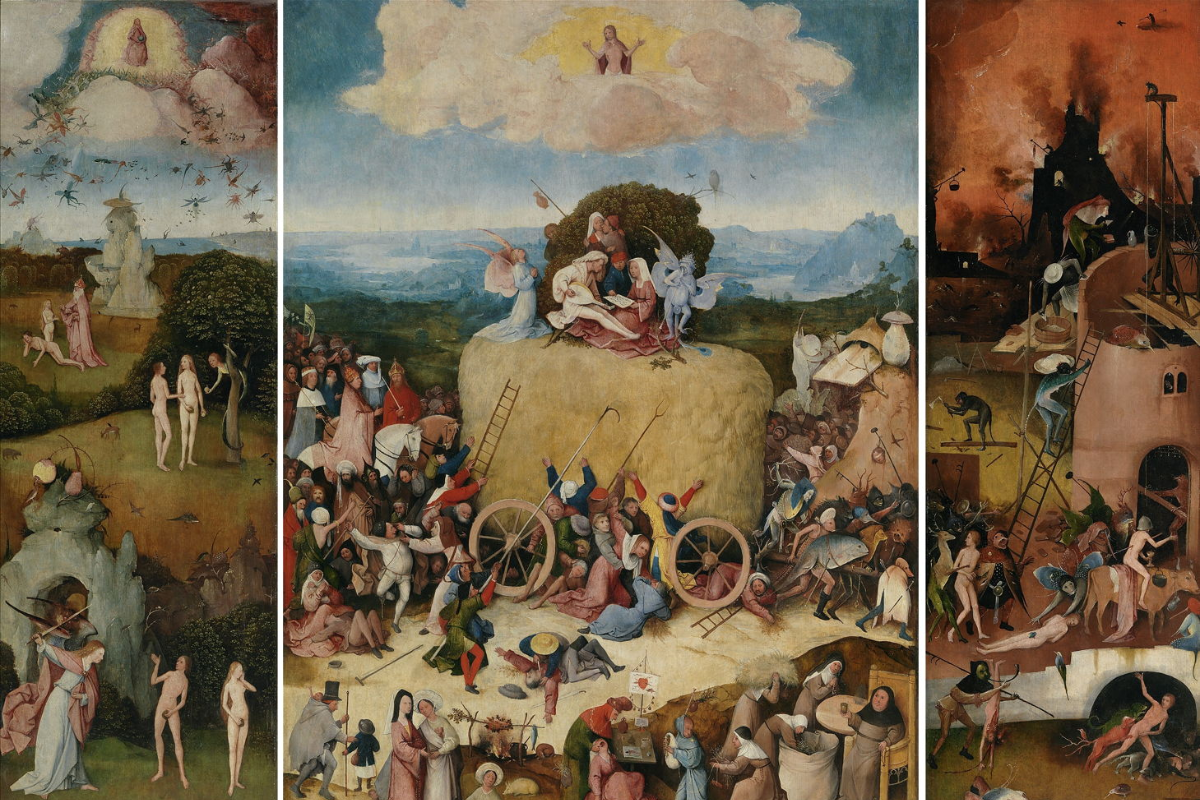

Marx and Engels, by contrast, put forward the view of scientific – materialist – socialism, emphasising that no quantity or quality of Great Men in previous epochs could have led society towards genuine socialism. Hence those communist tendencies that did exist within previous bourgeois revolutions, such as Winstanley’s Diggers in the English Revolution and the extreme left of the Jacobins around Hebert in the French Revolution French Revolution, were doomed to failure from the beginning.

In the final analysis, these movements and leaders represented the demands of a class – the working class – that was only in its nascency; demands that could not be achieved on the basis of the relatively basic productive forces that existed at that time, with little industry, no world market, and a numerically weak working class.

Similar too, as explained above, was the victory of Stalinism and the bureaucracy over Trotskyism and the Left Opposition in the years following the 1917 Russian Revolution. Socialism, as Trotsky explained in the Revolution Betrayed, could not be built in one country – and especially not in a country as economically and culturally undeveloped as Russia.

“Who makes history?”, asks Plekhanov in his pamphlet on the role of the individual in history. “It is made by the social man,” the formative Russian Marxist answers.

“But if in a given period he creates given relationships and not others, there must be some cause for it, of course; it is determined by the state of his productive forces.

“No great man can foist on society relations which no longer conform to the state of these forces, or which do not yet conform to them. In this sense, indeed, he cannot make history.” (Our emphasis in bold)

Thus, Plekhanov explains, even Great Men and Women are not free to make history as they please. But, again, the question of the relationship between freedom and necessity arises. Plekhanov continues:

“Social relationships have their inherent logic: as long as people live in given mutual relationships they will feel, think and act in a given way, and no other. Attempts on the part of public men to combat this logic would also be fruitless; the natural course of things (i.e. this logic of social relationships) would reduce all his efforts to naught.

“But if I know in what direction social relations are changing owing to given changes in the social-economic process of production, I also know in what direction social mentality is changing; consequently, I am able to influence it. Influencing social mentality means influencing historical events. Hence, in a certain sense, I can make history, and there is no need for me to wait while ‘it is being made’.” (Our emphasis in bold)

In other words, by understanding the general laws of motion in society – of the economy, consciousness, and revolution – we can ourselves become a factor in the objective process and help to determine the course of history.

And this is what is meant by theory: the understanding of these general laws, based on a materialist and dialectical analysis of nature, of history, and of capitalism; an understanding that provides a guide to revolutionary organisation and action, allowing us to radically change the world around us. “Theory,” as Marx noted, “becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses”.

A question of leadership

Ultimately, as mentioned at the start, it is the objective conditions of crisis and radicalised consciousness that bring the masses onto the scene of history, making revolution possible. Without these necessary conditions, there can be no talk of revolution.

Ultimately, as mentioned at the start, it is the objective conditions of crisis and radicalised consciousness that bring the masses onto the scene of history, making revolution possible. Without these necessary conditions, there can be no talk of revolution.

This is what Plekhanov was polemicising against in his famous pamphlet, quoted above; against the middle class Narodniks who placed too great an emphasis on the role of the individual, substituting the need for mass action and organisation with that of individual terror and ‘propaganda of the deed’. Such futile tactics continue through to today in the form of anarchism and its obsession with ‘direct action’, which more often than not amounts to little more than the performance of political stunts.

Plekhanov, by contrast, was attempting to imbue the early Russian Marxists with a sense of the importance of the masses in making history. And not just ‘the masses’ in the abstract, but the vital role of the organised working class – organised around the revolutionary ideas of Marxism.

Today, it is clear that all the objective conditions necessary for world revolution exist. Indeed, as Trotsky asserted in the opening passages of his Transitional Programme, “the objective prerequisites for the proletarian revolution have not only ‘ripened’; they have begun to get somewhat rotten.”

“Without a socialist revolution, in the next historical period at that, a catastrophe threatens the whole culture of mankind.”

The problem facing humankind in the current epoch, Trotsky emphasised, lies not with incorrect objective conditions, but with the lack of the subjective factor: the revolutionary party. “The historical crisis of mankind is reduced to the crisis of the revolutionary leadership.”

Everywhere we look, the old order is breaking down. There is a deep questioning of all the existing certainties in society, previously considered sacrosanct and inviolable; a radicalisation and discontent, reflecting itself in sharp swings to the left and to the right.

But as Trotsky eloquently explained in relation to the October Revolution and the crucial role of Lenin and the Bolsheviks 100 years ago, the prospect of change remains only as potential without the presence of a revolutionary leadership:

“Only on the basis of a study of political processes in the masses themselves, can we understand the role of parties and leaders, whom we least of all are inclined to ignore. They constitute not an independent, but nevertheless a very important, element in the process. Without a guiding organisation, the energy of the masses would dissipate like steam not enclosed in a piston-box. But nevertheless what moves things is not the piston or the box, but the steam.” (Leon Trotsky, The History of the Russian Revolution, Preface)

This is the role of a revolutionary organisation: to channel and direct the radical energy of the workers, youth, and oppressed masses – which exists today worldwide – towards the revolutionary transformation of society.

Building such an organisation is the task that we in the International Marxist Tendency have set ourselves. And on this centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution, we implore you to join us in this vital task.