100 years ago, the masses in Russia – led by the Bolsheviks – took power. For Marxists, this is undoubtedly the greatest event in human history; the first time – with the brief exception of the Paris Commune – when the oppressed and exploited rose up and overthrew the old order.

Despite what the slanderous bourgeois historians and defenders of the status quo say about the October Revolution of 1917 being a ‘coup’, the real motor force for these titanic events was none other than the masses themselves: the organised workers, peasants, and soldiers in the soviets.

Nevertheless, whilst the Revolution was ‘made’ by the masses, its success would ultimately not have been possible without the vital leading role of two individuals: Lenin and Trotsky. And even then, Trotsky was humble enough to admit that his was an auxiliary role compared to that of Lenin, whose years of patient work in building and educating the Bolsheviks were key in providing the revolutionary masses with the necessary organisation, direction, and leadership.

“Had I not been present in 1917 in Petersburg, the October Revolution would still have taken place – on the condition that Lenin was present and in command,” Trotsky remarked in his Diary in Exile.

“If neither Lenin nor I had been present in Petersburg, there would have been no October Revolution: the leadership of the Bolshevik Party would have prevented it from occurring – of this I have not the slightest doubt! If Lenin had not been in Petersburg, I doubt whether I could have managed to conquer the resistance of the Bolshevik leaders…But I repeat, granted the presence of Lenin the October Revolution would have been victorious anyway.”

Human agency and free will

What is true for the Russian Revolution is true of all pivotal changes in society. Most textbooks and documentaries would like us to believe that all historical progress is the product of ‘Great Men and Women’ with ‘Great Ideas’, in which the masses are merely the passive recipients of charismatic, determined, and resolute individuals.

The Marxist view of history, by contrast, in the words of Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto – emphasises that ultimately “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”.

Many academic critics attempt to paint Marxism as being rigid and mechanical, accusing the theories of scientific socialism (as Marx and Engels referred to their ideas) of being ‘economically deterministic’. Yet Marx never denied the importance of human agency in determining the course of history. Indeed, ‘history’, Marx stressed, is not some mystical force. There is no ‘destiny’ or ‘fate’.

“History does nothing, it possesses no immense wealth, it wages no battles. It is man, real, living man who does all that, who possesses and fights; ‘history’ is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.” (Marx and Engels, The Holy Family, emphasis in the original)

As Engels commented in a letter to Bloch, one of his German socialist peers:

“History is made in such a way that the final result always arises from conflicts between many individual wills, of which each in turn has been made what it is by a host of particular conditions of life. Thus there are innumerable intersecting forces, an infinite series of parallelograms of forces which give rise to one resultant — the historical event.”

History, then, is made up of individuals following their own individual aims and interests. But, in doing so, as Marx explained, people “inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production.”

Whilst we all have a relative degree of freedom about our choices in life, in other words, we are nevertheless forced by our economic position in society to make very definite decisions that are out of our control. If – like the vast majority of people in society – you are part of the working class, for example, without a wealth of shares and investments to your name that you can live off, then you have no real choice but to work for a wage in order to put food on the table. You might have a certain amount of freedom as to who you work for, depending on your circumstances, but ultimately you have to sell your labour-power (your ability to work) to the capitalist if you are to survive.

The landscape of history

As with individuals in general, so it is with the ‘Great’ individuals of history also.

Marxism does not deny the role of the individual in shaping history. Indeed, in certain cases, this can be a vital and central role. But even history’s ‘Great’ individuals can still only act within the limits set by the conditions of their time, which in turn are created by those who have come before them. As Marx famously commented in his writings on the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

In other words, even the most resolute, intelligent, and charismatic individuals are not completely free agents, but are constrained by the material conditions, social relations, and economic laws of their time.

Like raindrops on a hilly terrain, we each leave our own mark on the surrounding environment, shaping it as we flow through it. The accumulation of all these individual impacts, in turn, creates an historical landscape, the contours of which define the scope of the path travelled by future flows of water.

And whilst a flood of rain or great political earthquakes can inexorably alter the terrain forever, ultimately, in ‘normal’ times, the path we follow is constrained by this social topography that we find ourselves travelling along. Society’s past activities and previous historical events, in other words, constrain and limit the decisions and possibilities available to the individuals that follow – including the ‘Great’ individuals of history.

Accident and necessity

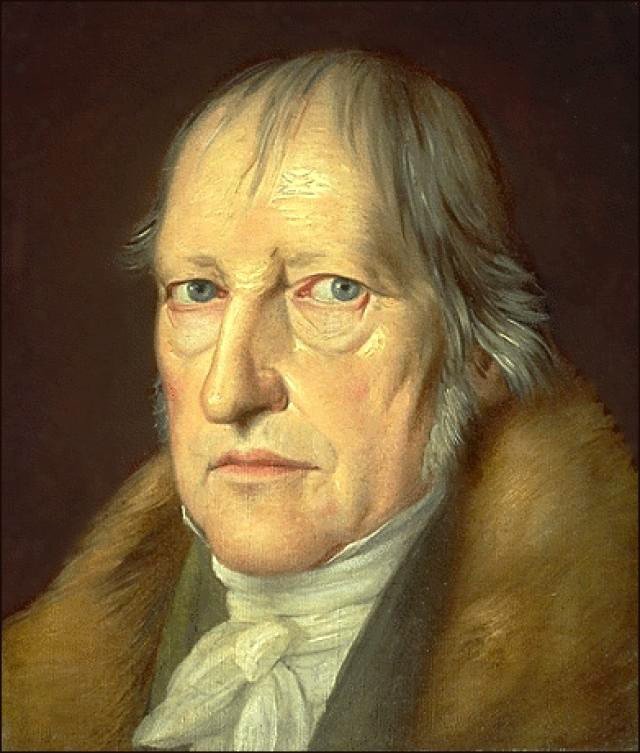

As the great dialectical German philosopher Hegel remarked, accident – ultimately – is a reflection of necessity. In this respect, the emergence of any particular ‘Great’ individual is largely ‘accidental’ in historical terms; ‘accidental’ in the sense that a similar historical role might have been played by another individual.

As the great dialectical German philosopher Hegel remarked, accident – ultimately – is a reflection of necessity. In this respect, the emergence of any particular ‘Great’ individual is largely ‘accidental’ in historical terms; ‘accidental’ in the sense that a similar historical role might have been played by another individual.

Even then, however, Engels noted in his own philosophical writings that the relationship between so-called ‘accident’ and ‘necessity’ is a dialectical one. “Common sense,” Engels writes in his Dialectics of Nature, “treats necessity and chance as determinations that exclude each other once for all. A thing, a circumstance, a process is either accidental or necessary, but not both.”

“What can be brought under general laws is regarded as necessary,” Engels continues; “what cannot be so brought as accidental.”

Applied to the study of history, we can therefore say that: whilst the emergence of a particular ‘Great’ individual is ‘accidental’, the emergence of a ‘Great’ leader or visionary in general is (at key moments) ‘necessary’.

In certain historical periods and conditions, in other words, the demands and needs of society will tend to create and call forth individuals with certain qualities and characteristics. In times when the class struggle is at its sharpest, for example, a leader is required who is firm and unwavering in their resolve.

Engels marvellously summarises this question of accident and necessity in relation to the ‘Great’ individuals of history in one of his letters:

“Men make their history themselves, but not as yet with a collective will or according to a collective plan or even in a definitely defined, given society. Their efforts clash, and for that very reason all such societies are governed by necessity, which is supplemented by and appears under the forms of accident. The necessity which here asserts itself amidst all accident is again ultimately economic necessity.

“This is where the so-called great men come in for treatment. That such and such a man and precisely that man arises at that particular time in that given country is of course pure accident. But cut him out and there will be a demand for a substitute, and this substitute will be found, good or bad, but in the long run he will be found. That Napoleon, just that particular Corsican, should have been the military dictator whom the French Republic, exhausted by its own war, had rendered necessary, was an accident; but that, if a Napoleon had been lacking, another would have filled the place, is proved by the fact that the man has always been found as soon as he became necessary: Caesar, Augustus, Cromwell, etc.” (Engels to Borgius, London, 25th January 1894)

Extending Engels’ point: it is clear that certain historical conditions will produce more ‘accidents’ than others.

In nature, any pool of water will consist of a collection of molecules, all with their own ‘random’ kinetic energies. Some of these molecules will contain enough energy to ‘accidentally’ evaporate off, even though the collective temperature of the water is not at boiling point. If you heat up the surrounding environment, however, the rate of evaporation will increase rapidly, until there is no water at all – only steam.

Similarly, in periods of intense class struggle, the masses will be radicalised and typically inert layers will be thrust into political action. And from this heightened stage of agitation will emerge more potential revolutionary leaders.

“A great man is great not because his personal qualities give individual features to great historical events,” remarked Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, “but because he possesses qualities which make him most capable of serving the great social needs of his time, needs which arose as a result of general and particular causes.” (G.V. Plekhanov, On the Role of the Individual in History)

The ‘Men of Destiny’, then, are those who express an idea that has already become necessary in processes taking place behind the backs of men and women. Whilst they see historical outcomes as the product of their own efforts and ideas, the scope for individual action is severely limited by objective reality, which favours one outcome over all others.

History is full of seemingly ‘accidental’ events – in economics, politics, etc.: this-or-that election result or blip in the market, for example. But in a situation of generalised crisis, more of such accidents are produced. The system becomes ever more sensitive to each additional accident, and the scales are weighed heavily in one direction by the accumulation of previous accidental events.

Historical events, then, are not completely predetermined. Nor, however, are they left completely to chance and luck. When history plays games with the fates of men and women, it always plays with a loaded dice.

The ‘necessity’ of history – of society or of a particular social class – in other words, creates the ‘accident’ of the ‘Great’ individual. It is not ‘Great’ men and women who make history, but history that makes certain men and women ‘Great’.

Whom the gods wish to destroy…

When history is behind you, it often seems like you can do no wrong. When history is against you, however, it seems like you can do no right.

When history is behind you, it often seems like you can do no wrong. When history is against you, however, it seems like you can do no right.

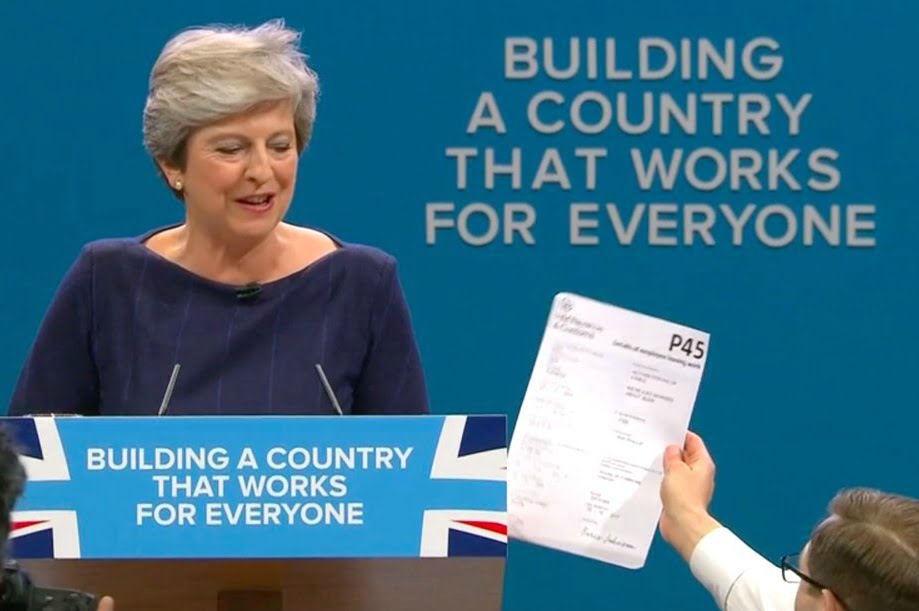

The latter case is presumably what it must feel like to be Theresa May right now. The Prime Minister’s future hangs in the balance after a series of shocks, scandals, and setbacks for her government. There was, for example, the Tory leader’s terrible – and largely unfortunate – closing speech at the Conservative Party conference in October, which was hampered from start-to-finish by events outside of her control: a fitful cough; a disruptive prankster; and some collapsing scenery. Now the knives are out for May, and many are predicting that she does not have long left in No.10 Downing Street.

As the Ancient Greek proverb goes, however: whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad.

Leon Trotsky paraphrases this saying in his History of the Russian Revolution when discussing “The Death Agony of the Monarchy”. But it also aptly describes Theresa May’s situation at the present time. In the wake of the humiliating general election result earlier this year, it now seems (at the time of writing) like everything is going wrong for the Tory Party leader .

At root, May’s misfortune and apparent incompetence reflects the impasse of the system that she defends and the lack of any future that it – and her party – has to offer. “The impersonal Jupiter of the historical dialectic,” Trotsky continues, “withdraws ‘reason’ from historic institutions that have outlived themselves and condemns their defenders to failure.”

In these quotes above, Trotsky was describing the personal failings of Tsar Nicholas II and the Russian royal family, whose hopelessness in their final hours before the February Revolution of 1917 – the author notes – mirrored that of previously overthrown monarchies, such as that of Charles I in England and Louis XVI in France.

In all these cases, the limits and demise of these once-omnipotent figures were a product of the anachronistic institution of the feudal monarchies that they represented. To paraphrase Joseph de Maistre, the 19th Century philosopher (and, ironically, a devout monarchist): every ruling class gets the leaders it deserves.

“The scripts for the rôles of Romanov and Capet were prescribed by the general development of the historic drama,” Trotsky states; “only the nuances of interpretation fell to the lot of the actors.”

“The ill-luck of Nicholas, as of Louis, had its roots not in his personal horoscope, but in the historical horoscope of the bureaucratic-caste monarchy.”

Individuality

It is a basic tenet of materialist philosophy that similar conditions produce similar results. We see this in nature with the question of evolution by comparing different species that have similar appearances.

For example, the dolphin is a mammal; the shark a fish; and the ichthyosaurus a now-extinct marine reptile. Each of these creatures is from a completely different branch of the evolutionary tree, and yet they have all been shaped by their shared environment to have almost identical appearances.

Equally, as mentioned above, both Engels and Trotsky noted how similar personalities and individual characters arise out of similar historical conditions – for example, with the ‘strong men’ of Caesar, Napoleon, and Stalin in periods where the class struggle reaches an intense deadlock.

Undoubtedly every individual has their own personality, which is the complex and dynamic product of a whole history of experiences and events. Nevertheless, as Trotsky explains in relation to the Russian monarchy (providing an astounding materialist analysis of psychological traits and personal characteristics in the process), the more intense the contradictions in society and the more powerful the overall forces of history, the more and more individual responses will converge and personal characteristics will end up conforming to fit the shape required.

“Similar (of course, far from identical) irritations in similar conditions call out similar reflexes; the more powerful the irritation, the sooner it overcomes personal peculiarities. To a tickle, people react differently, but to a red-hot iron, alike. As a steam-hammer converts a sphere and a cube alike into sheet metal, so under the blow of too great and inexorable events resistances are smashed and the boundaries of ‘individuality’ lost.”

Just as Thatcher declared that “there’s no such thing as society”, we might therefore retort that there is no such thing as the individual. We are all products of our environment, whilst also shaping the world around us. And in certain historical periods, the needs and aims of many individuals combine to create the conditions for revolutionary change – and, in turn, to thrust to the fore revolutionary leaders who can take society forwards.

Hitler and the rise of Fascism

Bourgeois historians too often use personal characteristics to explain away those abominations of history that they do not and cannot understand. Hence the rise of Fascism, World War Two and the atrocities of the Holocaust are put down to the individual monstrosity of Adolf Hitler.

Bourgeois historians too often use personal characteristics to explain away those abominations of history that they do not and cannot understand. Hence the rise of Fascism, World War Two and the atrocities of the Holocaust are put down to the individual monstrosity of Adolf Hitler.

Marxists, by contrast, explain these figures not in terms of their personality, but in terms of historical conditions and processes.

Hitler’s actions, for example, certainly shaped the course of history. But he himself was also a product of the period that he lived through: a period that saw the emasculation and humiliation of Germany after WWI, epitomised by the imposition of the Treaty of Versailles. Above all, Hitler and the mass Fascist movement that he represented arose out of an age of revolution and counter-revolution – a chaotic and turbulent time that saw the German masses (and, in particular, the middle classes) crushed by the impact of Weimar-era hyperinflation and the Great Depression.

The result was the creation of a large layer of impoverished petit-bourgeois, caught between monopoly capitalism on the one side and the radicalised working class – who were looking towards Communism – on the other. It was this ruined and frenzied middle-class mass that provided the social basis for the rise of Fascism and, in turn, Hitler, who promised to restore this layer to their former economic glory. The backing of the German bourgeoisie and the criminal split in the working class – as a result of the actions of Social Democratic leaders and Stalinists – prepared the way for his victory.

It is clear, therefore, that the rise of an upstart such as Hitler was not accidental, but was the result of an entire historical period. This is further demonstrated by the fact that similar figures and movements – such as Mussolini in Italy and Franco in Spain – were seen around the same time as a result of similar conditions across Europe.

This is not to suggest, however, that the conquest of power by any one of these Fascist movements or leaders was inevitable. The objective conditions of crisis and the formation of a destitute, desperate middle class most certainly provided the material basis for the rise of Fascism in Italy, Germany, and Spain. But, in the final analysis, their victory was only made possible as a result of the missing subjective factor – that is, a real revolutionary leadership – on the side of the working class.

This period of German history, for example, was a long, tumultuous process in which many parties, ideas, and leaders were put to the test and found-wanting: from the failure of the German Communist Party to make the call for workers’ power in 1923; to the ultra-left sectarianism of the Third Period Stalinists, who refused to form a united front with the Social Democrats that could have stopped Hitler and the burgeoning Fascist movement in its tracks. (And this is not to even mention the bourgeois Chancellors of Brüning, Papen, and Schleicher during the decline of the Weimar Republic, whose impotence paved the way for Hitler’s ascent to power.)

Upon taking power, Hitler boasted that he had done so “without breaking so much as a single pane of glass”. But the sad reality is that this was only possible as a result of the crimes of the leadership of the working class. In this sense, we again see the vital role of the individual in history, only this time in the negative: the barbarism that can occur in the absence of the revolutionary subjective factor.

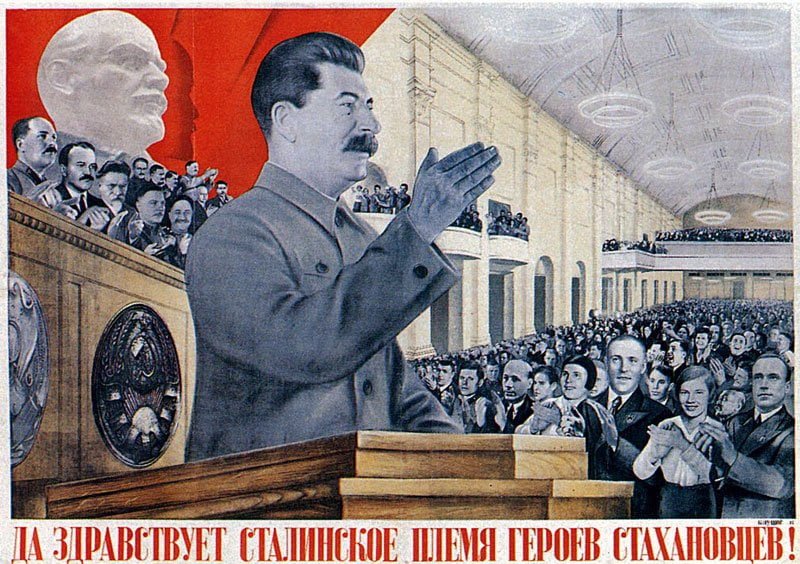

‘Strongmen’ and the ‘Cult of Personality’

Just as the horrors of the Second World War are often presented as being simply the result of Hitler’s personal malevolence, so too are the crimes of Stalinism and Maoism frequently reduced to the ‘Cult of Personality’ surrounding the respective leaders in the Soviet Union and China.

Just as the horrors of the Second World War are often presented as being simply the result of Hitler’s personal malevolence, so too are the crimes of Stalinism and Maoism frequently reduced to the ‘Cult of Personality’ surrounding the respective leaders in the Soviet Union and China.

Again, the appeal of such a superficial analysis to bourgeois historians is all too clear. It is easy to reduce complex historical process to semi-mystical personal attributes such as charisma and charm. It is far harder to examine these processes in a rigorous and scientific – that is, a materialist – way, in order to understand the underlying forces at play.

‘Strongmen’ such as Stalin and Mao were ultimately the representatives of a bureaucratic caste, which in turn arose out of the attempts to build a socialist planned economy within conditions of economic backwardness and isolation.

The ‘Cult of Personality’ surrounding Stalin flowed from this reality, reflecting the need of the Soviet bureaucracy for a supreme leader who could personify and defend their interests; as Trotsky explains in his Marxist masterpiece, the Revolution Betrayed, which analyses the degeneration of the Russian Revolution into bureaucratic totalitarianism:

“The increasingly insistent deification of Stalin is, with all its elements of caricature, a necessary element of the regime. The bureaucracy has need of an inviolable superarbiter, a first consul if not an emperor, and it raises upon its shoulders him who best responds to its claim for lordship. That ‘strength of character’ of the leader which so enraptures the literary dilettantes of the West, is in reality the sum total of the collective pressure of a caste which will stop at nothing in defense of its position. Each one of them at his post is thinking: l’etat c’est moi. In Stalin each one easily finds himself. But Stalin also finds in each one a small part of his own spirit. Stalin is the personification of the bureaucracy. That is the substance of his political personality.” (Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, chapter XI)

As Trotsky further explained in his uncompleted biography of Stalin, the blandness of this brute – ‘the grey blur’ – reflected the stultifying and narrow-minded mentality of the Soviet bureaucracy, whose interests he ultimately represented.

“[In order for the ‘Cult of Personality’ around Stalin to emerge], special historical conditions were necessary in which he was not required to display any creativeness. His [lack of] intellect served merely to summarise the work of the collective intellect of the bureaucratic caste as a whole. The bureaucracy’s fight for its self-preservation, the entrenchment of its privileged position, called for the personification of an intense will to power. Such an exceptional configuration of historical conditions was necessary before his intellectual attributes, notwithstanding their mediocrity, received extensive general recognition multiplied by the coefficient of this will.” (Leon Trotsky, Stalin, chapter XIII)

Marx, in the 18th Brumaire, made similar remarks about Louis Bonaparte, even coining the term ‘Bonapartism’ to describe such leaders that regularly appear throughout history: those who rule by the sword, leaning on the different classes within society in order to rise up and maintain order (that is, to maintain the status quo of the existing property relations) in a situation where the class struggle has reached a deadlock.

In this sense, there is also a similarity between the original Bonaparte (Napoleon I) and Julius Caesar, who likewise acted as a ‘strongman’, arising amidst the demise of the Roman Republic in order to provide a relative stability and order within society – and, ultimately, to defend the interests of the existing ruling class of slave-owners. For these reasons, the term ‘Caesarism’ is also sometimes used to describe the same types of regimes as might be labelled ‘Bonapartist’.

Trotsky, in turn, described Stalinism as a form of ‘Soviet Bonapartism’: a political dictatorship, sitting atop a planned economy and a workers’ state, arising from a situation in which the revolutionary masses and objective conditions for socialism were too weak within Russia alone, but where the old capitalist class had been swept aside, into the dustbin of history.

Describing the similarities between the historical phenomena of Caesarism, Bonapartism, and Stalinism (and, in turn, between the historical figures of Caesar, Bonaparte, and Stalin), Trotsky wrote the following:

“Caesarism, or its bourgeois form, Bonapartism, enters the scene in those moments of history when the sharp struggle of two camps raises the state power, so to speak, above the nation, and guarantees it, in appearance, a complete independence of classes in reality, only the freedom necessary for a defense of the privileged. The Stalin regime, rising above a politically atomised society, resting upon a police and officers’ corps, and allowing of no control whatever, is obviously a variation of Bonapartism – a Bonapartism of a new type not before seen in history.

“Caesarism arose upon the basis of a slave society shaken by inward strife. Bonapartism is one of the political weapons of the capitalist regime in its critical period. Stalinism is a variety of the same system, but upon the basis of a workers’ state torn by the antagonism between an organized and armed Soviet aristocracy and the unarmed toiling masses.” (Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, chapter XI)

‘Strongmen’ such as Stalin (and Caesar, Napoleon, etc.) arise historically, therefore, not simply because of their single-minded resolve or unrelenting ambition, but – as Trotsky explains above – because the social contradictions of certain periods demand such authoritarian leadership.

Indeed, the irony is that Stalin rose to power not because of any ‘Cult of Personality’, but precisely because of his lack of charisma and personality. Far from being a broad and confident thinker, the Soviet dictator was marked by his mediocrity, as Trotsky notes in his biography of Stalin, quoting the words of Engels about the Duke of Wellington: “He is great in his own way, as great as one can be without ceasing to be a mediocrity.” (Leon Trotsky, Stalin, chapter XIII)

Marx commented similarly about Louis Bonaparte (Napoleon III) in the 18th Brumaire, noting that Bonaparte’s lack of personality or charisma too (as with Stalin) acted as a blank slate, upon which various groups could project their aspirations and interests. Such dull, uninspiring, and lacklustre qualities, therefore, allowed Bonaparte and Stalin to maintain a veneer of being ‘all things to all people’, despite in fact defending the privileges of the existing ruling class.

Trotsky vs Stalin

One can compare and contrast the lives of Trotsky and Stalin to see clearly how different epochs demand different sorts of individuals.

One can compare and contrast the lives of Trotsky and Stalin to see clearly how different epochs demand different sorts of individuals.

Trotsky, on the one hand, was well known for his charismatic presence and sharp intellect. He had been chairman of the 1905 St Petersburg Soviet at the age of just 26; he was the leader of the Military Revolutionary Committee that organised the 1917 October insurrection; and he single-handedly forged the Red Army from nothing as the People’s Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs during the Russian Civil War.

Stalin, by contrast, had played little role in the 1917 Revolution. So how did he come to be the ‘Great Leader’ of the Soviet Union? This simple – yet seemingly paradoxical – question highlights the relationship between the individual and history.

The bland and boring personalities of Stalin (or Louis Bonaparte) stand in stark contrast to the daring, audacity, and genius of those individuals pushed forward by the wave of revolution, which requires and rewards genuine talent.

In its ascendancy, the revolutionary movement produces figures with courage and conviction: the Cromwells, Robespierres, and Lenins of this world. The period of degeneration and backsliding, however, favours those without theories or visions. As the revolution ebbs and the masses withdraw from activity, then the dull, grey ‘strongman’ emerges on the back of this demoralisation to maintain order.

Trotsky and Lenin – bold and far-sighted leaders and theoreticians – represented the revolutionary fervour of 1917. But by the time of Lenin’s death in 1924, after years of civil war, famine, and devastation, the masses were tired and did not want to listen to calls for ‘permanent revolution’. Instead, the mentality (particularly amongst the vast peasantry) was one of a desire for stability; of an end to the chaos, whilst retaining the gains of the October Revolution.

At the same time, under intense conditions of isolation and economic backwardness, the masses withdrew from political activity. And without the presence of advanced industry, mass literacy, high levels of education, and abundant technical skills, etc., the material conditions for the development of workers’ control and management simply did not exist.

As Trotsky explained in the Revolution Betrayed, it was ultimately these conditions of scarcity and deprivation that formed the material basis for the Stalinist regime:

“The basis of bureaucratic rule is the poverty of society in objects of consumption, with the resulting struggle of each against all. When there is enough goods in a store, the purchasers can come whenever they want to. When there is little goods, the purchasers are compelled to stand in line. When the lines are very long, it is necessary to appoint a policeman to keep order. Such is the starting point of the power of the Soviet bureaucracy. It ‘knows’ who is to get something and how has to wait.” (Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, chapter V)

In turn, this bureaucratic caste, as explained earlier, demanded a figurehead who represented their narrow interests. Trotsky himself even remarked that had he taken power after Lenin’s death – for example, through his leadership of the Red Army – he would have ended up becoming instead a prisoner of the military bureaucracy. Lenin’s wife Krupskaya, meanwhile, noted in 1926 that had Lenin survived, he too would have ended up in one of Stalin’s prisons.

Trotsky, therefore, understood what so many shallow and empirical historians since have failed to recognise: that the cause for the degeneration of the Soviet Union into totalitarian dictatorship lay not with the ideas of Marxism, Leninism, and Bolshevism, nor with the megalomaniacal personality of Stalin, but because of the impossibility of building ‘socialism in one country’ – and especially in an economically undeveloped, mainly peasant-based country such as Russia; that is, because the Revolution did not successfully spread internationally.

The rise of the Soviet bureaucratic machinery and, in turn, of Stalin, flowed from this fact. “Stalin rose to power not thanks to personal qualities, but to an impersonal apparatus,” Trotsky explains in his biography of the tyrannical dictator. “It was not he who created the apparatus, but the apparatus that created him.” (Leon Trotsky, Stalin, chapter XIV)