“The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution,” remarked Lloyd George to the French Premier Clemenceau in March 1919. The ending of the bloody conflict of the so-called Great War of 1914-18 coincided with (and was in effect brought about by) the German Revolution of November 1918.

Coming just one year after the mighty events of Red October in Russia, power was taken into the hands of the masses. Yet the socialist revolution ultimately failed. The consequences of that failure would be most brutally felt over a decade later with the rise of fascism in Germany and the consolidation of Stalinism in Russia.

Why did the revolution occur and why did it fail? Rob Sewell, author of an important new Marxist analysis of this dramatic historical period, Germany 1918 – 1933: Socialism or Barbarism (available through Wellred books) provides an answer to these important questions as we mark the centenary of the 1918 German Revolution.

Jan Valtin, a member of the Spartacist League of Youth, relates what happened:

“That night I saw the mutinous sailors roll in to Bremen in caravans of commandeered trucks – red flags and machine guns mounted on the trucks…

“The population was in the streets. From all sides masses of humanity, a sea of swinging, pushing bodies and distorted faces was moving toward the centre of the town. Many of the workers were armed with guns, with bayonets, with hammers.”

On their own initiative, the revolutionaries established a Workers’ and Sailors’ Council, which took control of the town. That night, workers and sailors carrying torches swept through the narrow streets singing the “Internationale” and meeting with no resistance. The following day, power was firmly in the hands of the workers in this naval stronghold.

On 4th November, the flames of revolution continued to spread, characterised by red flags flying over official Imperial buildings. On 6th November, Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Workers’ Councils took power in Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck. On 7th and 8th November, Dresden, Leipzig, Chemnitz, Magdeburg, Brunswick, Frankfurt, Cologne, Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Munich all followed suit.

However, it was not until 9th November, the official date of the revolution, that Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils were established in Berlin, the capital, at none other than the Supreme Army headquarters!

Soviets spread

The “liberal” cabinet of Prince von Baden had met in emergency session on 7th November, with the SPD ministers increasingly shocked by the spread of so-called anarchy. “We have done all we can to keep the masses on the halter,” stated SDP leader Scheidemann. But far more was needed to subdue the revolution and these leaders proved to be willing and obedient tools.

The “liberal” cabinet of Prince von Baden had met in emergency session on 7th November, with the SPD ministers increasingly shocked by the spread of so-called anarchy. “We have done all we can to keep the masses on the halter,” stated SDP leader Scheidemann. But far more was needed to subdue the revolution and these leaders proved to be willing and obedient tools.

With the collapse of the old state apparatus, power had fallen into the hands of the armed workers, sailors and soldiers. As in Russia in 1905 and 1917, the masses set up workers’ councils or soviets, the embryos of workers’ power.

The councils or soviets were the most flexible and democratic system ever devised. They were elected not on the basis of geographical constituencies, but in factories, offices, farms and other places of work.

Events were moving very quickly and a situation of “dual power” coloured everything. Not a wheel turned, not a whistle blew, without the workers’ say-so. The revolution was like a strike, but on a massive scale.

In Berlin, new revolutionary committees were being set up. A Berlin Executive Committee of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils had been established which acted as a national centre for the councils that had been established throughout the country. In the absence of any elected parliament or assembly, this body was the most representative national body in existence.

Kaiser flees

The old order was at an end. Everywhere the imperial flags were being pulled down and replaced with red flags. Events moved quickly as the Hohenzollern dynasty followed the Romanovs into oblivion.

The old order was at an end. Everywhere the imperial flags were being pulled down and replaced with red flags. Events moved quickly as the Hohenzollern dynasty followed the Romanovs into oblivion.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, Emperor of all Germany, was forced to abandon his Royal palace at Potsdam and the question of his abdication was on everyone’s lips. Wilhelm had been reluctant to abandon his throne. But Prince Max von Baden, appointed by Wilhelm, announced the Kaiser’s demise without the decency of telling him.

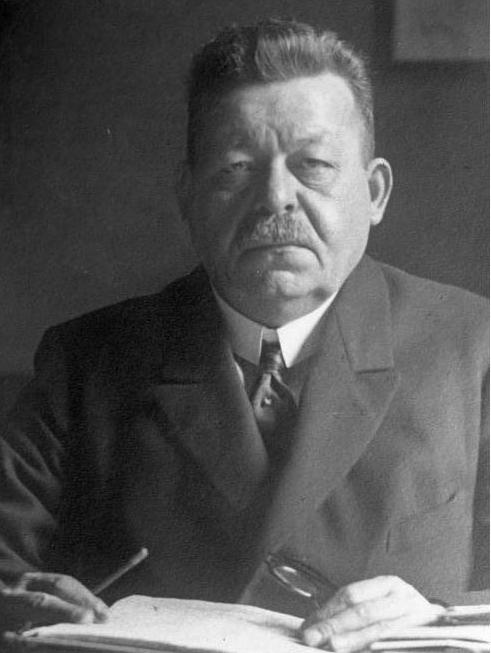

Then von Baden approached Ebert, the Social Democrat, and asked: “If I should succeed in persuading the Kaiser [to abdicate], do I have you on my side in the battle against the social revolution?” Ebert replied: “If the Kaiser does not abdicate the social revolution is inevitable. I do not want it – in fact I hate it like sin.”

The armed mass demonstrations in Berlin terrified von Baden so much that he decided to tender his resignation as Chancellor with immediate effect and hand over the reins of government to the right-wing Social Democrats. But before departing, he pondered the options:

“The revolution is on the verge of winning. We cannot crush it but perhaps we can strangle it… if Ebert is presented to me from the streets as the people’s leader, then we will have a republic; if it is Liebknecht, then Bolshevism.”

The power vacuum had to be filled urgently with a safe pair of “reformist” hands. The Social Democratic leaders were thus thrust into power.

Ebert began to piece together a new government. He was astute enough to realise that he needed a “left” cover if he was to succeed and therefore invited the Independent Social Democratic Party to join it. An all-socialist government would be formed, hoping it would be enough to stem the tide of revolution. Ebert’s first act as Chancellor was an appeal for calm:

“Fellow Citizens! I beg of you, leave the streets. A city of law and order!”

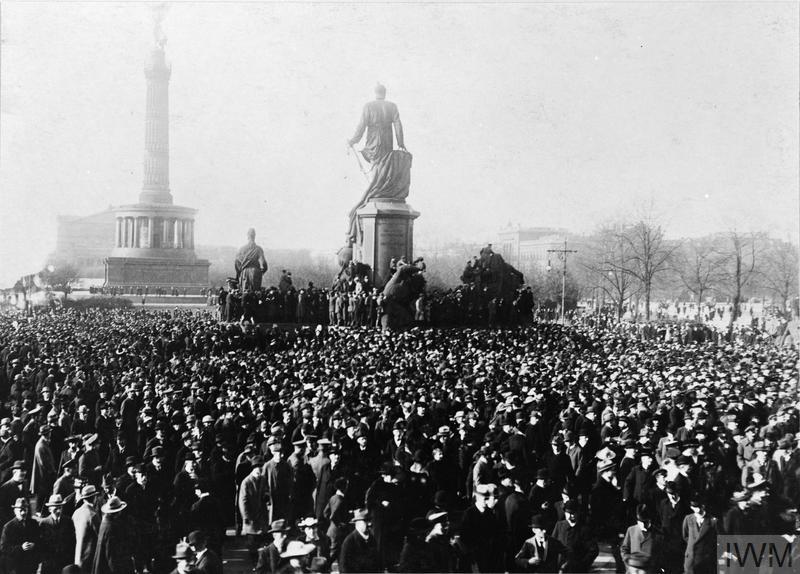

But the masses did not stay away from the streets. On the contrary, after the factories had been saturated with leaflets calling for an insurrection, workers began marching to the centre of Berlin.

Revolutionary tide

Scheidemann, the Majority Socialist vice-Chancellor, heard loud cries from the enormous crowds outside the Reichstag building. “I saw the Russian madness before me, the replacement of the Tsarist terror by the Bolshevist one. No! Not in Germany.” From the balcony, he announced the news that Ebert had now agreed to become Chancellor of a socialist government. “Long live the German Republic!”, he proclaimed.

Scheidemann, the Majority Socialist vice-Chancellor, heard loud cries from the enormous crowds outside the Reichstag building. “I saw the Russian madness before me, the replacement of the Tsarist terror by the Bolshevist one. No! Not in Germany.” From the balcony, he announced the news that Ebert had now agreed to become Chancellor of a socialist government. “Long live the German Republic!”, he proclaimed.

Karl Liebknecht then climbed onto the Reichstag balcony and made a proclamation on behalf of the Spartacist League (the main Marxist group in Germany at the time), which ended with the call for a German Socialist Republic:

“We now have to strain our strength to construct the workers’ and soldiers’ government and a new proletarian state, a state of peace, joy and freedom for our German brothers throughout the whole world. We stretch out our hands to them, and call on them to carry to completion the world revolution. Those of you who want to see the free German Socialist Republic and German Revolution, raise your hands!”

Amongst the assembled masses, a sea of hands was raised in favour of revolution. Shortly afterwards, a symbolic red flag was hoisted on the Emperor’s flagpole.

Ebert was furious when he heard that Scheidemann had proclaimed the Republic. “You have no right to proclaim the Republic!”, he shouted.

The revolutionary tide was sweeping aside all before it and the proletariat was on the move. In Berlin, the jails were thrown open and hundreds of prisoners were set free, including Leo Jogiches, the Spartacist organiser.

Another, Rosa Luxemburg, was also released from Breslau prison. On that day, the Reichstag building surrendered without a shot being fired. If the masses had wanted to, they could have taken power peacefully at this time, but they lacked a revolutionary leadership.

Workers’ power

The revolutionary fervour gripping the masses increased, despite the appeals of the Social Democratic leaders. The revolution had conquered the streets and workers and soldiers could feel the potential power in their hands.

The revolutionary fervour gripping the masses increased, despite the appeals of the Social Democratic leaders. The revolution had conquered the streets and workers and soldiers could feel the potential power in their hands.

However, in the vast majority of cases, the revolutionary workers looked to the leaders of their traditional parties, the SPD and USPD, for a way forward.

On 10th November, a meeting of the Berlin Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council, in the presence of 3,000 delegates, officially proclaimed itself the representative of the revolutionary people. Furthermore, it took the decision to appoint a Council of People’s Commissars under the control of the Executive Council.

However, the only problem was that Ebert had already been appointed the head of the Imperial government by Prince von Baden the previous day. In addition, the Majority Socialists vehemently rejected any suggestion that they should be accountable to the Council’s Executive Committee.

However, the leaders of the SPD and the USPD had come to an agreement to set up a six-member cabinet, which adopted the name “Council of People’s Representatives”. This was then ratified by the Berlin Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council.

For the Workers’ Councils, it was “their” socialist government, appointed by them. But rather than purge the civil service, the government chose to rely on the discredited bureaucratic apparatus of Prince Max von Baden.

Given the impact of the revolution, the government tried to balance between these competing forces. It simultaneously rested on the apparatus of the old ruling class but it also had to take account of the power of the Workers’ Councils. This peculiar development was a direct product of the “dual power” situation existing in the country.

Social Democrats

On 12 November, the new government issued a proclamation addressed to the German people setting “itself the task of putting into effect the socialist programme”.

On 12 November, the new government issued a proclamation addressed to the German people setting “itself the task of putting into effect the socialist programme”.

The German bosses had no other choice but to make concessions – despite their previous opposition – as a result of the pressure of the revolution. This included the right of assembly, freedom of expression, abolition of censorship, amnesty for political offences, provisions to protect labour and other reforms. Above all, it stipulated that “a maximum working day of eight hours will enter into force on 1 January 1919.”

While the “socialist unity” government of Ebert talked in radical terms, even promising socialisation of certain industries, its aim was not the overthrow of German landlordism and capitalism but the introduction of measures to stabilise the situation.

Nobody could deny these were important gains, but militarism had not been eradicated and the power of the old regime was still in place. Despite this, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg demanded the completion of the revolution and the establishment of a German Workers’ Republic, but they were in a minority.

The right-wing Social Democrats increasingly acted as a mouthpiece of “law and order”, behind which stood the capitalists and the military chiefs. They were willing collaborators with the most reactionary sections of society, irrespective of the bloodshed, to achieve this aim. However, Ebert understood very well that the government could not use these forces immediately. They had to wait.

Most ordinary Social Democratic members had no trust in the General Staff and were in favour of some kind of people’s army. This was especially the case with the soldiers’ councils. Of course, this was anathema to the generals.

As the Quartermaster General Groener later revealed: “We made an alliance against Bolshevism… There existed no other party which had enough influence upon the masses to enable the re-establishment of a governmental power with the help of the army.”

Behind Ebert stood the old order masquerading as “democrats”, and behind them stood the Freikorps, the reactionary dregs of society.

On 16th December, the National Congress of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils was held in Berlin. However, the domination of the SDP elements proved decisive. After a heated debate, the Congress came out strongly in support of the calling of a National Assembly. This was a blow to the revolutionaries. It now looked as if the revolution was slipping through their fingers.

Spartacist Paul Frölich said that, compared to inside the Congress, the “social reality outside the Congress doors was very different”. It reflected the fact that the capital was politically more advanced than the provinces, while the provinces provided a counterweight to the feelings of “Red Berlin”, where the USPD had influence. It also reflected the weight of the more conservative soldier representatives, compared to those from the factories.

The mass demonstration which converged on the Congress demanded, among other things, the democratic transformation of the army. As a result, the Congress supported a bill of rights for democratising the military. It demanded: (1) the abolition of the standing army and the establishment of a people’s militia, (2) that all badges of rank be removed, (3) that all soldiers be allowed to elect their officers with immediate right of recall, and furthermore (4) soldiers’ councils would be responsible for the maintenance of discipline throughout the armed forces.

The SPD ministers, led by Ebert, were faced with an officers’ revolt. As expected, the Social Democrats capitulated and set out to establish even closer links with the German High Command. To further this relationship, they flagrantly defied the demands and decisions of the Congress.

After the first flush of the November Revolution, the German High Command, in connivance with Ebert, made plans to occupy Berlin with a number of hand-picked divisions of “loyal” troops to establish a reliable and “firm government”.

Attempted coup

An attempted military coup took place on 6th December, when reactionary troops marched on the Chancellery, proclaiming Ebert as President.

An attempted military coup took place on 6th December, when reactionary troops marched on the Chancellery, proclaiming Ebert as President.

Groener’s troops – the shock troops of the counter-revolution – began to arrive in the capital and were greeted by Ebert. It was hoped he would restore order. But within a short space of time, things began to unravel. The ordinary soldiers began to fraternise with the radicalised Berlin workers. The troops had become totally unreliable, which destroyed any plans to impose a dictatorship.

Following on from the failed coup of 6th December, the military leaders, in league with the Chancellor, once more decided to assert themselves. The pretext for this intervention came on 23rd and 24th December, when open clashes occurred between regular army troops and rebel sailors of the Peoples’ Naval Division. The Division were stationed at the Imperial Palace, in the centre of Berlin. The government clearly saw them as a threat to their authority. Following a government provocation, the angry sailors broke into the Command Headquarters, seized the Chief of Command, Otto Wels, and demanded he sign a document stating the division would not be transferred. But Wels refused and was held hostage by the marines.

On the pretext of releasing Wels, Ebert ordered government troops under General Lequis to intervene using force. But many soldiers refused to obey their officers and the assault came to a chaotic end.

Counter-revolution

The outrage over this attack had serious political repercussions. On 29th December 1918, the left-wing USPD ministers resigned from the government in protest at this “bloodbath”. This represented a deep governmental crisis. The right-wing Social Democrats now took full responsibility for pursuing the course of counter-revolution.

The outrage over this attack had serious political repercussions. On 29th December 1918, the left-wing USPD ministers resigned from the government in protest at this “bloodbath”. This represented a deep governmental crisis. The right-wing Social Democrats now took full responsibility for pursuing the course of counter-revolution.

Towards the end of December, an alliance of monarchists and counter-revolutionary elements of various descriptions (together with the SPD leaders), conducted a vicious witch-hunt against the Spartacist League, the representatives of German Bolshevism.

A murderous atmosphere was being deliberately fostered against Liebknecht and Luxemburg, regarded as the leaders of the revolutionary movement. It was the equivalent of the July Days in Russia.

Many politically backward and reactionary layers were consciously worked up into a state of hysteria about the Spartacists, who were falsely accused of plunging the country into chaos.

This was to result, with the connivance of the SDP leaders, in the tragic murder of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg on 15 January 1919. This opened a new stage in the German Revolution.