One hundred and fifty years ago, on 28th September 1864, the International Working Men’s Association, more commonly known as the First International, was born. This first international proletarian organisation paved the way for the growth of working class organisation and spread of Marxism worldwide. In its day, the ruling class trembled before this revolutionary menace.

“Workers of the world: unite!”

As its name implies, it was the first time an international organisation of the working class had come into being. The need for such an organisation flowed from the position of the working class internationally. Capitalism is a global system, based upon a world division of labour and the world market. The position of the working class is the same the world over and therefore the struggle of the working class is the same.

Given the character of capitalism, the struggle of the working class and the movement towards socialism must be international. The struggle for socialism is international or it is nothing. There can be no such thing as “socialism in one country.” The task of the socialist revolution is the abolition of private ownership of the means of production and the nation state, a product of capitalism.

On this basis, with the abolition of national barriers and the establishment of a world federation of socialist states, can the stranglehold of private profit be eliminated and the resources of the planet be used freely for the benefit of all.

In the words of Marx and Engels, “the workers have no country” and consequently, “workers of the world unite! The responsibility for this struggle falls on the shoulders of an international organisation of the working class.” It was with this in mind that Marx organised the First International.

The International Working Men’s Association (IWMA), which was founded in St. Martin’s Hall, London in September 1864, was not a Marxist organisation. In fact it was composed of a whole number of tendencies: British reformist trade unions, French Radicals, followers of Proudhon, followers of the Italian Mazzini, as well as Russian anarchists. Nevertheless, given his stature, Marx became its outstanding leader, drafting its famous Inaugural Address and Rules and guiding its work.

Although the British working class had engaged in trade union and political struggles, most notably in the Chartist movement, the working class was only just emerging as a force in Europe and America. While socialist ideas, such as those of Robert Owen, Saint-Simon, and Fourier, had taken a certain hold, the workers’ movement was still in its infancy. While these early ideas offered a bold critique of capitalism, they were mostly utopian schemes not rooted in the class struggle.

Scientific socialism

In the years prior to the founding of the First International, Marx and Engels had laid down the foundations of scientific socialism, based upon the development of history and the class struggle. The fundamental ideas of Marxism were contained in the Communist Manifesto, a revolutionary document written in 1848 for an international workers’ party.

In the years of reaction following the defeat of the revolutions of 1848, Marx and Engels kept in close contact with the leaders of the labour and democratic movement in a variety of countries. Their work, in arguing for the independent action of the workers, had laid the theoretical and practical basis for the founding of the First International.

Marx threw himself into the establishment of the IWMA. He attended the founding conference as a representative of the German workers and played a vital role in its proceedings.

The conference appointed a Provisional Committee to draw up the rules of the association, and it fell to Marx to draft a programme that would unite the various tendencies in the working class movement, and give the organisation a class, proletarian character, as opposed to a kind of mutual benefit society, as advocated by the reformist elements. Marx’s work in the International proved to be a milestone, and served to promote the ideas of what became known as Marxism within the international movement.

As Corresponding Secretary for Germany, Marx stood out as a guiding light within the International’s leading body, the General Council. Its weekly proceedings, captured in its minutes, are a catalogue of the organisation’s activities, the development of the workers’ movement, as well as the struggle to broaden its ideas and understanding.

Marx used his skills to the maximum in seeking to unite into a single international army the individual contingents of the European working class. This proved to be a mammoth task, given the very diverse political levels at which each section stood.

He nevertheless succeeded in drawing up a programme that would not exclude either the British trade unions, nor the French, Belgium, and Swiss Proudhonists, nor the German Lassalleans. Only in this flexible fashion could the mass character of the International be assured.

As Marx wrote to Engels on 4th November 1864, “It was very difficult to frame the thing so that our view should appear in a form that would make it acceptable to the present outlook of the workers’ movement. In a couple of weeks, the same people will be having meetings on the franchise with Bright and Cobden. It will take time before the revival of the movement allows the old boldness of language to be used. We must be bold in content, mild in manner.”

The emancipation of the working class

It was the prime task of Marx at this time to assure the proletarian character of the organisation against the encroachment of capitalist politicians seeking to use the movement for their own ends. In this, he continually sought to strengthen the working class core of the General Council and achieve a truly international representation.

The General Rules of the Association, written by Marx, opened with the statement, “That the emancipation of the working class must be the task of the working class itself; that the struggle for the emancipation of the working class means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule.”

The Inaugural Address, again written by Marx, stressed its working class objective: “To conquer political power has therefore become the great duty of the working class.” It concluded with the words of the Manifesto: “Proletarians of all countries, Unite!” As a result of this firm stand, most of the middle class elements had abandoned the Council by the spring of 1865.

Through its energetic work, the International established firm links with the British trade unions. The first national conference of trade unions in Sheffield in July 1866 passed a resolution urging trade unions to join the International Working Men’s Association since “it is essential to the progress and prosperity of the entire working community”. In 1867 more than 30 trade unions, numbering around 50,000 members, were affiliated. This is even more remarkable given that these were skilled workers’ unions, which represented the more conservative sections of the class. The mass of unskilled workers remained unorganised at this time.

Sections of the International were quickly established in the United States and on the continent of Europe, including Russia. In Germany, the International took the initiative in establishing trade unions and played not an unimportant role in the founding of the German Social-Democratic Labour Party.

The struggle for higher wages

Marx used every opportunity to put forward his ideas according to the concrete situation. In the spring of 1865, John Weston, a member of the General Council, brought up a proposal that it was useless and even harmful for workers to fight for wage increases, based on the falsehood that wage increases cause price rises. Marx took the opportunity to debate with Weston and to explain his economic theories. In conclusion, Marx proposed the following resolution which elaborated his views on the trade unions to the General Council:

“Firstly. A general rise in the rate of wages would result in a fall of the general rate of profit, but, broadly speaking, not affect the prices of commodities.

“Secondly. The general tendency of capitalist production is not to raise, but to sink the average standard of wages.

“Thirdly. Trades unions work well as centres of resistance against the encroachment of capital. They fail partially from an injudicious use of their power. They fail generally from limiting themselves to a guerrilla war against the effects of the existing system, instead of simultaneously trying to change it, instead of using their organised forces as a lever for the final emancipation of the working class, that is to say, the ultimate abolition of the wages system.”

Marx’s report was eventually published by Eleanor Marx in 1898, under the title “Value, Price and Profit”, and remains today a classic introduction to Marxist economics.

The Inaugural Address also took a stand on foreign policy and stated that it was the duty of the working class “to master themselves the mysteries of international politics.” The International therefore came out boldly for progressive causes internationally. During the American Civil War (1861-65), the International gave its support to the industrial states of the North against the insurgent slave-owning states of the South. The British workers rallied to the Northern cause and opposed the policy of the British government which supported the slaveowners and thereby prevented Britain’s interference in the Civil War.

While Marx did not, of course, consider Abraham Lincoln a communist, this did not prevent him or the International expressing their deep sympathy for the revolutionary struggle he led against slavery. The International sent a message of greetings to President Lincoln, written by Marx, who in turn greatly appreciated the International’s moral support.

Theory and practice

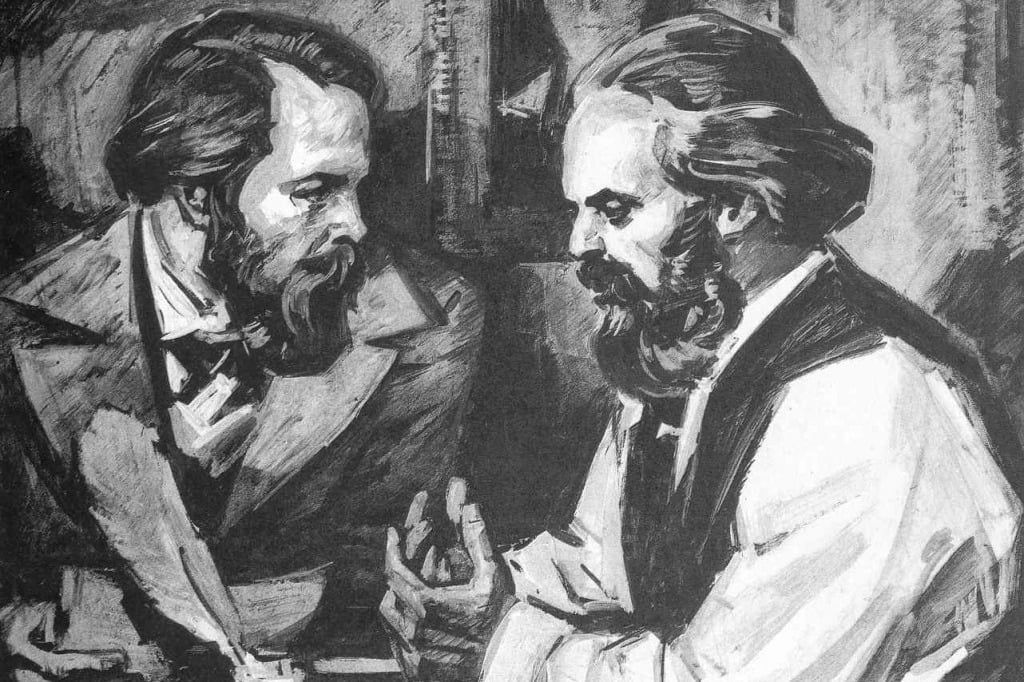

Marx collaborated actively with Engels regarding his work in the General Council, as can be seen from their correspondence. Engels was unable however to directly participate in the Council until his move to London in 1870. During their years in the International, they gathered around them a galaxy of worker leaders, gifted people devoted to the cause. Marx and Engels constantly widened their international circle of collaboration, especially with the Germans, most notably Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel.

Marx has been continually portrayed as an “armchair revolutionary”, who simply occupied himself in the reading room of the British museum. As can be seen from his work in the International, this was certainly not the case. Whilst Marx stressed the essential importance of theory, without which there can be no revolutionary movement, he regarded theory and practice as inseparable. Theory without practice is a knife without a blade. His years of practical work in the International are a clear expression of this outlook.

By 1870, sections of the international existed in more than ten countries. Organisationally they were still weak and many of them had to operate semi-legally and sometimes completely underground. The sphere of influence of the International and its ideas, however, was immeasurably broader than the direct limits of its sections; tens and sometimes hundreds of thousands of workers were involved in its campaigns. At this time, the bourgeoisie trembled before the spectre of Communism in the form of the International.

Bakunin and Anarchism

As the International spread its influence, it attracted the anarchists who played a negative and disruptive role within its ranks. At first, Bakunin, the anarchist leader, attempted to organise his own revolutionary association in Italy. He then moved to Switzerland and was elected to the leadership of the League for Peace and Freedom. In 1868, he left the League and founded the International Social-Democratic Alliance. This body applied to the General Council to join the International as a separate organisation, with its own constitution and its own programme. The General Council categorically refused the request as this would have paralysed the International, but agreed however to admit its local groups if the Alliance officially disbanded.

In a manoeuvre, Bakunin agreed but continued to operate as before but as a secret body with the aim of hijacking the International. The Bakuninists declared war on God and State but reduced its programme to the abolition of the right of inheritance. Rather than the working class as the class to change society, Bakunin preferred the intelligentsia, the students, and the bourgeois democrats. The anarchists dismissed out-of-hand the political struggle of the working class for political power, which they regarded as opportunism. While the anarchist Alliance put forward the demand of “equalisation of classes”, the International advocated the “abolition of classes”.

The first major clash with the anarchists occurred at the Basle Congress in September 1869. Their attempt to impose pseudo-revolutionary swagger on the International would have reduced the International to a sect. Such a precondition would have alienated the International’s members and caused disunity in the European working class movement. They regarded such Anarchy as a good thing.

The Bakuninists intrigued at every stage to subvert the International and undermine its leadership, beginning with Marx. They continually slandered Marx as a “dictator” and the General Council as being “authoritarian”. They even accused Marx of being an agent of Bismarck.

In reality, it was Bakunin’s circle which attracted all kinds of unsavoury types, including agent provocateurs and other agents, keen to promote friction and disunity wherever possible.

The Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (18 March to 29 May, 1871) saw the workers of Paris seize political power. They “stormed heaven”, to use Marx’s expression, and established the embryo of the first workers’ state in history. The “old boldness” returned, as Marx proclaimed the unconditional support of the General Council for the Communards. Unfortunately, due to the mistakes of its leaders, the Commune was defeated.

Nevertheless, the International rallied to its defence. “Let the sections of the International Working Men’s Association in every country stir the working classes into action”, wrote Marx in the Second Address of the General Council. “If they forsake their duty, if they remain passive, the present tremendous war will be but the harbinger of still deadlier international feuds, and lead in every nation to a renewed triumph over the workman by the lords of the sword, of the soil, and of capital.”

As the tone of the International became more radical, the British trade union leaders were becoming more conservative. They were frightened by the attacks of the Old Order on the revolutionary Commune and its supporters, especially the International. They thus swiftly deserted the International. At the end of May, the last of the Communards were butchered in cold blood.

“You know that throughout the period of the last Paris revolution I was denounced continuously as the ‘ringleader of the International’ by the Versailles papers (Stieber collaborating) and following them by the press here”, wrote Marx to Kugelmann, 18th June, 1871.

“It [the Address] is making the devil of a noise and I have the honour to be at this moment the best calumniated and the most menaced man of London. That really does one good after a tedious twenty years’ idyll in the backwoods. The government paper – The Observer – threatens me with legal prosecution. Let them dare! I don’t care a damn about these scoundrels!”

The International helped in every way to take care of the refugees who fled France, collecting money and resources. Marx drew an extremely important lesson from the Commune: “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machine, and wield it for its own purposes.” The old state apparatus had to be smashed and replaced with a new workers’ state on the lines of the Commune.

“Of late, the Social-Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome horror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat”, stated Engels later. “Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.”

The defeat of the Paris Commune created unfavourable conditions for the International. The British trade unions withdrew from the General Council. The German movement suffered defeat at the hands of repression, which saw the imprisonment of Bebel and Liebknecht. The French labour movement was completely paralysed. In the end, the French workers were represented in the International by a host of refugees, affected by bitter factional strife. This poisoned atmosphere was carried over into the General Council.

Conflicts with Bakunin

At this time too, fed by the defeat, the struggle with the anarchists reached new heights. According to Jenny Marx, Marx’s daughter, “During several months they succeeded in carrying their intrigues into every country. They went to work with such wild energy that for some time things looked bad for the future of the International.”

Nevertheless, Marx and Engels repeatedly took up the struggle. As a regular congress was impossible in view of the reaction, a conference of the International was held in London, in September 1871, where the issue of the political struggle was once again taken up. Despite the protests of the Bakuninists, they were politically defeated. The conference passed the following resolution:

“In presence of an unbridled reaction which violently crushes every effort at emancipation on the part of the working men, and pretends to maintain by brute force the distinction of classes and the political domination of the propertied classes resulting from it;…

“That this constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to insure the triumph of the social Revolution and its ultimate end – the abolition of classes;

“That the combination of forces which the working class has already effected by its economical struggles ought at the same time to serve as a lever for its struggles against the political powers of landlords and capitalists.

“The Conference recalls to the members of the International: That in the militant state of the working class, its economical movement and its political action are indissolubly united.”

Immediately following the Conference a still more savage struggle broke out. Stung, the Bakuninists openly declared war on the General Council and demanded a full Congress to settle the matter.

By the time this Congress was held at the Hague in September 1872, the battle lines were drawn. Marx was present but Bakunin was absent. After the debate on political action, the position of the General Council was again ratified. The Bakuninists were routed. Marx later wrote that the history of the International was “a continual struggle on the part of the General Council against the sects and amateur experiments which attempted to maintain themselves within the International itself against the genuine movement of the working class.”

A special commission which examined all the documents pertaining to Bakunin’s Alliance came to the conclusion that this society had been operating as a secret organisation within the International, and proposed the expulsion of Bakunin and Guillaume, which was adopted.

The legacy of the First International

At the end of the Congress, on the proposal of Engels, it was decided to move the headquarters of the International to New York. The political climate had dramatically changed in Europe after the defeat of the Commune, where in many countries membership of the International had become a crime.

The upswing of capitalism had put enormous pressure on the organisation. The Hague Congress proved to be the last one in the history of the First International. It existed for a few more years but in 1876 the International Working Men’s Association was formally dissolved.

The International’s historic work, together with its programme and principles, trained the working class in the spirit of proletarian internationalism and served to consolidate the labour movement in a number of countries. In Germany that process reached its culmination in founding in 1869 of the first political party to unite the working class on the basis of Marxism. This proved to be a catalyst. Not long after Marx’s death, a revival took place in the labour movement.

By 1886 there was talk of the organisation of a new International. The work of Marx and Engels in the First International had born fruit, as they had foreseen. In July 1889, the Second International was formed but this time the new International was composed of mass parties of the working class, which openly embraced the principles of Marxism.

It is this revolutionary international programme, tradition, and method of Marx – like an unbroken thread – that is upheld today by the International Marxist Tendency.