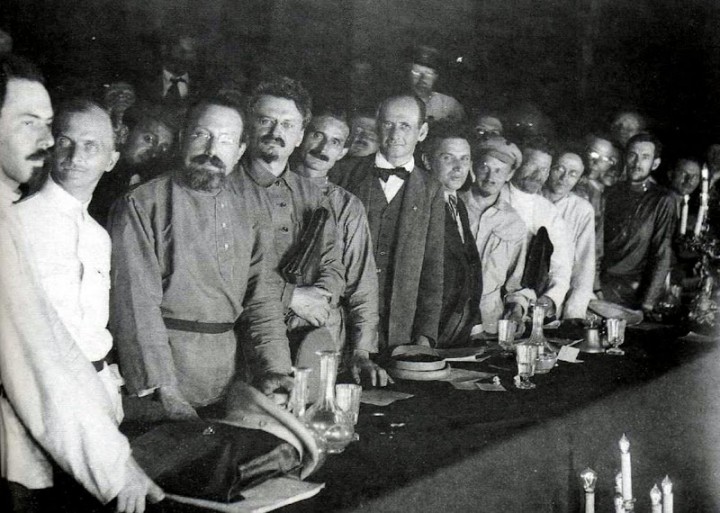

In its early years, the Communist International was the general staff of the world revolution. Its congresses represent the highest peak achieved to date by the struggle for the emancipation of the proletariat. Here was a mass international organisation of the working class, led by the leaders of the first successful proletarian revolution, that truly threatened the future of capitalism itself.

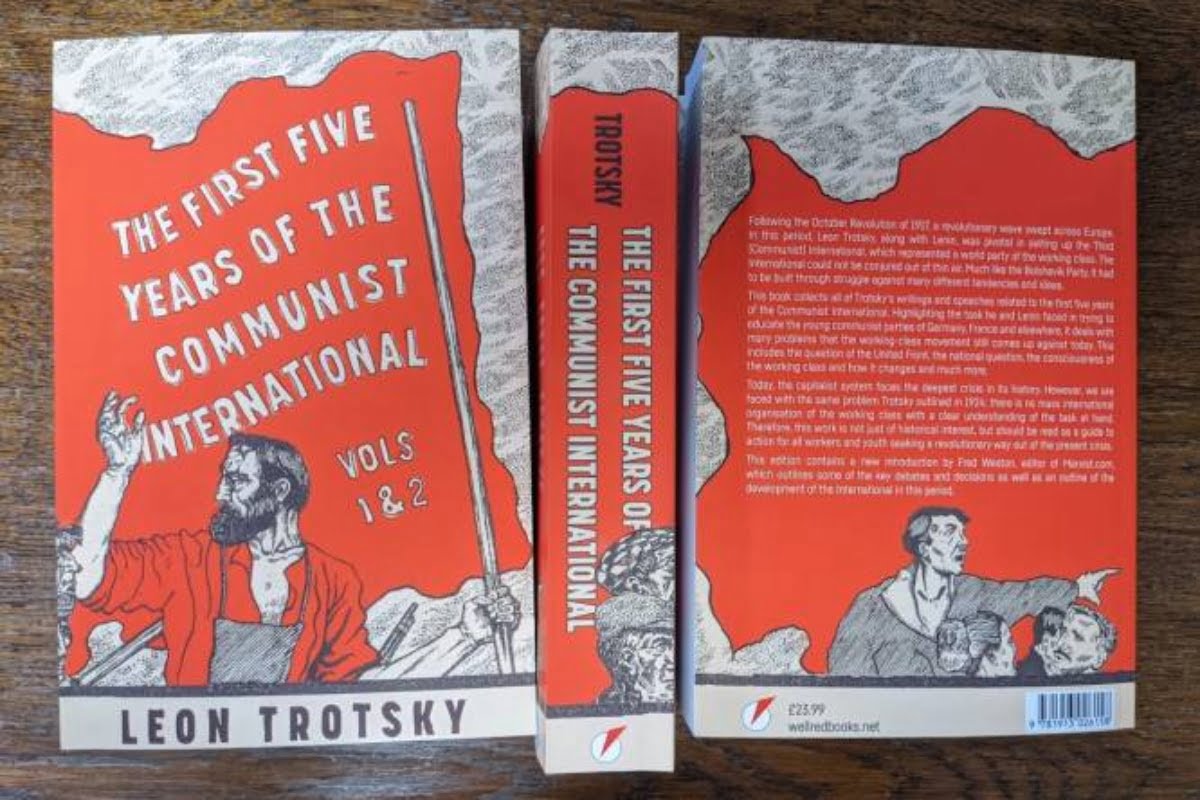

This book contains all of the key speeches, reports and articles that Trotsky wrote for the International at this time. It is a treasure trove of lessons in Marxist strategy and tactics, and the method of analysing the class struggle through its various stages.

Buy your copy of The First Five Years of the Communist International from Wellred Books today!

The Communist International’s creation and rapid growth reflected a contradiction: on the one hand, capitalism was in its deepest ever crisis, and the workers of the world were drawing increasingly revolutionary conclusions, as shown by the German Revolution in 1918. On the other hand, these workers lacked any serious revolutionary organisations and leaders capable of leading them to the overthrow of capitalism. The working class had inherited the rotten leaders of social democracy from the past, and lacked the time to carefully build new, revolutionary organisations and leaders, who were up to the task.

What impresses the reader is the range and depth of his analysis, and of his grasp of the need to build everywhere a highly flexible yet intransigent ‘combat organisation’ of the working class. Trotsky is bringing the priceless lessons of the Russian Revolution and the decades of building the Bolshevik Party, to a world that was getting a very rude revolutionary awakening. It is clear that Trotsky frequently understands the situation in different countries much better than the comrades from those countries do. The detail, nuance and flexibility of Trotsky’s arguments, and the breadth of his knowledge, all these stand as a testament and proof of internationalism in principle: that is, of the necessity for a truly international leadership that can generalise the lessons from this or that country and carefully apply them to concrete situations.

What impresses the reader is the range and depth of his analysis, and of his grasp of the need to build everywhere a highly flexible yet intransigent ‘combat organisation’ of the working class. Trotsky is bringing the priceless lessons of the Russian Revolution and the decades of building the Bolshevik Party, to a world that was getting a very rude revolutionary awakening. It is clear that Trotsky frequently understands the situation in different countries much better than the comrades from those countries do. The detail, nuance and flexibility of Trotsky’s arguments, and the breadth of his knowledge, all these stand as a testament and proof of internationalism in principle: that is, of the necessity for a truly international leadership that can generalise the lessons from this or that country and carefully apply them to concrete situations.

Some of the speeches and articles, such as the ‘Manifesto for the Second World Congress’, deal with the aftermath of World War One, especially the acute economic crisis that Europe faced. The perspectives that Trotsky outlines are highly relevant today, especially the explanation of the chronic crisis and historic impasse of capitalism at that stage.

The ‘Report on the World Economic Crisis and the New Tasks of the Communist International’ is another masterpiece of perspectives, and contains very useful material for those wanting to understand the nature of an organic, global crisis of capitalism, of a system being suffocated by its own mountains of debt, speculation and inflation. But Trotsky also shows the all-sided character of his thought here. Despite stressing the organic nature of the world crisis, he also raises the possibility that capitalism will be able to recover if it is not overthrown, and that in these circumstances it may even eventually experience a new boom. In other words, he anticipated the post-war boom. Of course, the main point at that time was the crisis and the opportunities for revolution, but Trotsky understood that the Communist International did not have unlimited time, nor any automatic path, to overthrowing capitalism.

Perhaps the richest parts of the book are to be found in Trotsky’s debates with the young French, German and Italian communist parties over questions of opportunism and sectarianism. Thanks to the revolutionary wave sweeping Europe at the time, the Communist International was able to quickly win large sections in France and Italy from the old reformist social democratic parties. However, this quick victory brought with it problems of an opportunist character.

It should go without saying that a Communist organisation is first and foremost a strictly revolutionary organisation, dedicated to the overthrow of capitalism. Therefore, Trotsky spent considerable time in the congresses of the Comintern, and in articles, exposing the reformist and careerist layers still present in the French Communist Party (PCF), for he knew that a party still in large part led by such elements, and with a blurred line between revolution and reform, would be incapable of leading the French working class to the conquest of power. In ‘The Conditions for Entering the Third International’, Trotsky explains that “for a considerable section of the representatives of official French Socialism this parting from the Second International [to join the Communist International] has nothing in common with a renunciation of the latter’s methods, but is instead a mere manoeuvre with the object of further deceiving the toiling masses.”

Trotsky attacks the Socialist Party leader Jean Longuet’s inability to extricate himself from the rarefied and smug “artificial atmosphere of parliamentarianism”, and his public display of “courtesy before the assembled body” of parliamentary “colleagues”. On the contrary, Trotsky explains that a genuine communist’s “aim is to show the workers the real role of parliament and of the parties represented there… In a workers’ newspaper it is impermissible to write about the parliament and its internal struggles in the style of journalists discussing among themselves in a cloakroom in parliament.” (‘On l’Humanité, the Central Organ of the French Party’)

These words have a powerful resonance in the aftermath of Corbynism’s strangulation in the viper’s nest of the British Parliament. Marxists must have no illusions in parliament whatsoever, which was and remains a talking shop completely removed from the lives of working class people.

The persistent opportunism of the French Socialist Party led Trotsky to ask some very pointed questions of its leaders before their admission to the Communist International. In ‘The Conditions for Entering the Third International’ (part of ‘On the Coming Congress of the Comintern’) Trotsky asks them if they “consider it permissible to support the French bourgeois republic directly or indirectly in those military clashes with other states which might arise?”, and “for Socialists to participate in a bourgeois government either in peace time or in war?” He then poses a demand point blank: will the French Socialist Party “initiate an energetic campaign among the working masses in favor of purging the French trade union movement of Jouhaux, Dumoulin, Merrheim and other betrayers of the working class? Yes or no?”

It was for these reasons that the famous 21 Conditions of Admission to the Communist International, which were adopted at the Second Congress in 1920, were drafted. Trotsky’s aim was not to build the largest possible Communist International as quickly as possible. His attitude is summed up in the same article, in which he writes that:

“The Communist International contemptuously rejects all those conventionalities which used to entangle relations within the Second International from top to bottom; and which had as their mainstay this, that the leaders of each national party pretended not to notice the opportunist, chauvinist declarations and actions of the leaders of other national parties, with the expectation that the latter would repay in the same coin.”

What stands out here is Trotsky’s courage and farsightedness. Having conquered power in Russia, it would be easy to lose one’s head and chase after a bigger and bigger Communist International, ‘pretending not to notice the opportunism’ of its new adherents. But instead he carefully fought against reformism and actively reduced the size of the Communist International with these clear conditions. Lenin and Trotsky understood well the lessons, not only of the Bolsheviks’ success in October 1917, but also of the failures of the parties of the Second International, that is that, in order to take power, the working class needs a disciplined, intransigent revolutionary organisation. Watering this down to get a bigger party will only lead to disaster in the decisive moment. As he says in his ‘Letter to Comrades Cachin and Frossard’, “If we simply slur over our differences with the syndicalists and the anarchists, these differences can later break catastrophically over our heads at the decisive moment.”

Sectarianism and the United Front

On the other hand, this revolutionary firmness must not be mistaken for ultra-left sectarianism. Paraphrasing the Communist Manifesto, in the ‘Manifesto of the Second World Congress’, Trotsky writes that,

On the other hand, this revolutionary firmness must not be mistaken for ultra-left sectarianism. Paraphrasing the Communist Manifesto, in the ‘Manifesto of the Second World Congress’, Trotsky writes that,

“The Communist International is the world party of proletarian uprising and proletarian dictatorship. It has no aims and tasks separate and apart from those of the working class itself. The pretensions of tiny sects, each of which wants to save the working class in its own manner, are alien and hostile to the spirit of the Communist International… Waging a merciless struggle against reformism in the trade unions and against parliamentary cretinism and careerism, the Communist International at the same time condemns all sectarian summonses to leave the ranks of the multimillioned trade union organisations or to turn one’s back upon parliamentary and municipal institutions. The Communists do not separate themselves from the masses who are being deceived and betrayed by the reformists and the patriots, but engage the latter in an irreconcilable struggle within the mass organisations and institutions established by bourgeois society, in order to overthrow them the more surely and the more quickly” (our emphasis).

So, having been absolutely clear that Communists have no illusions whatsoever in parliament, and work to overthrow it, Trotsky is in turn absolutely clear that Communists must also be prepared to work within reformist organisations and parliament “in order to overthrow them the more surely and the more quickly”.

Many of these statements are directed against the sectarianism of the German KAPD, which refused outright any work in parliament and the trade unions. Trotsky’s characterisation of this ultra-leftism is very apt, politically and psychologically. He reveals its barrenness in On the Policy of the KAPD:

“Comrade Gorter thinks that if he keeps a kilometer away from the buildings of parliament that thereby the workers’ slavish worship of parliamentarianism will be weakened or destroyed… a wholesale denial of parliamentarianism is sheer superstition. In the long run, as like two peas in a pod, so such a denial resembles a virtuous man’s dread of walking the streets lest his virtue be subjected to temptation. If you are a revolutionist and a Communist, working under the genuine leadership and control of a centralised proletarian party, then you are able to function in a trade union, or at the front, or on a newspaper, or on the barricade, or in the parliament; and you will always be true to yourself, true to what you must be – not a parliamentarian, nor a newspaper hack, nor a trade unionist, but a revolutionary Communist who utilises all paths, means and methods for the sake of the social revolution.”

Similar arguments, rich in tactical detail, are to be found in the articles and speeches on the United Front. This tactic was developed in the aftermath of the failures of the German Revolution, and as the initial explosion of enthusiasm for the Communist International subsided. Lenin and Trotksy realised the task of winning the majority of the working class still lay ahead of the International, in most countries, and it was necessary to find a road to the workers still under the influence of reformism.

Trotsky masterfully takes up the ultra-left idea of a ‘united front from below’ that would exclude the treacherous reformist leaders. In ‘On the United Front’ he points out that “If we were able simply to unite the working masses around our own banner or around our practical immediate slogans, and skip over reformist organisations, whether party or trade union, that would of course be the best thing in the world. But then the very question of the united front would not exist in its present form.” He draws on the experience of the Russian Revolution, stating that “we Russian Communists were willing, even after our October victory, to permit Mensheviks and SRs to enter the government, and we actually did draw in the Left SRs.”

In other words, the most resolute and revolutionary communists must be prepared, temporarily, to ‘unite with’ reformist leaders, but not “to re-educate Scheidemann, Blum, Jouhaux and Co., [i.e., reformist leaders] but to blow apart the conservatism of their organisations and to cut a path to action by the masses” (‘From the ECCI to the Paris Convention of the French Communist Party’)

This review has only skimmed the surface of the 800 pages of this treasure trove of Marxist strategy and tactics. The articles and speeches criticising the centrist leaders of the Italian Socialist Party are particularly useful for understanding the role of a Bolshevik, cadre organisation, instead of a loose party that plays with the phraseology of revolution but is not prepared to carry it through. I cannot recommend this masterpiece enough to anyone who wants to become a cadre in a Bolshevik organisation that is seriously training itself for the conquest of power by the working class, that is, in the IMT.

Thus, the Communist International’s, and particularly Lenin and Trotsky’s, task was to fast track the education of a new layer of revolutionary leaders and organisations so that they might meet the coming revolutionary situations with the necessary strength. Throughout these 800 or so pages, Trotsky takes the members of the new International through a school of Bolshevism.