“The last hour has come; the fate of our country and the dynasty is being decided.”

So said a panicked telegram to Tsar Nicholas II from the head of Tsarist Russia’s Duma, Mikhail Rodzianko, on the eve of the February Revolution in 1917.

Rodzianko was correct – though it was not just the fate of Russia and the Romanovs being decided by the Russian masses; it was the fate of the entire world.

The February Revolution opened up nine months of storm and stress. This reached a crescendo with the October Revolution, which sent ripples across the globe.

But while October saw the working class – allied with the peasantry – finally take power, the February Revolution was a different case. It resulted in the establishment of two contending forces, emerging from the dust of the insurrection, marking the beginning of a state of ‘dual power’.

Lenin’s intervention into this situation was decisive, characterised by a firm commitment to class independence. He placed absolutely zero faith in the bourgeois liberals who made up the Provisional Government.

Lenin’s mistrust of the liberals may appear obvious to us today – particularly in countries where so-called liberal ‘democracy’ prevails, and where liberals stand completely exposed and discredited.

In countries run under dictatorial regimes – that of Putin’s Russia, for example, or China – the liberals can gain a radical appearance. This can cause confusion for layers of the working class, who may come to view these liberals as potential allies.

Is there not unity in numbers? Should revolutionaries not collaborate with all forces who want to overthrow a given capitalist regime? The death of Navalny in Russia has brought this question to the fore once again.

Lenin’s Marxist policy of class independence, however, remains more true today than ever. Indeed, without this firmness in principle, the October Revolution would not have been possible. Class collaboration leads to ruin.

Lead up

Lenin said that all revolutions begin from the top. This was certainly the case within Tsarist Russia. With the war going from bad to worse, there was a growing number of ruling-class plots against the Romanov family, such as the murder of Rasputin.

But discontent was not confined to the upper classes. The war was placing increasing pressure on Russian society as a whole. The masses were beginning to stir.

The situation in the trenches was dire. Mutinous feelings were spreading like wildfire, evidenced by the tone in letters sent home.

“They’ve put out an order that there will be no peace until full victory,” one said. “Tell your comrades that we all ought to stage an uprising against the war.”

And at home, for ordinary workers, the situation was none too good either. Long bread lines were a common sight. These began to turn into bread riots by 1917.

Alongside such riots came strikes. January saw the largest since before the war. 145,000 workers came out in Petrograd – the industrial heartland of Russia, and its capital at the time.

Such strikes were not merely over wages, but raised political demands. They saw the self-organisation of workers, with mass meetings alongside the withdrawal of labour.

This only escalated. By early February the workers from the huge Putilov works in Petrograd came out. Not only were they calling for higher wages, but revolutionary demands were adopted: “Down with the government! End the war!”

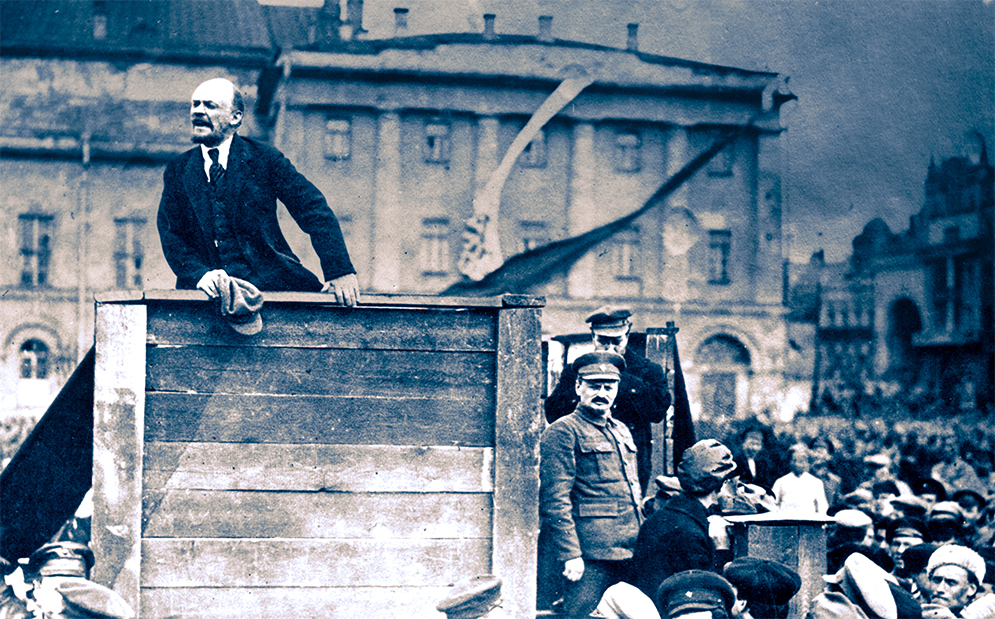

Then came 23 February (in the old Russian calendar, or 8 March in the modern calendar), International Women’s Day. The women workers came out onto the streets, physically dragging male workers out of the factories to stand alongside them.

Revolutionary slogans went up, thousands of workers came out, and thousands more joined them in following days. The revolution had begun.

Liberals

The attitude of the bourgeois liberals to this was one of panic and passivity. Their method of ‘struggle’ against the autocracy had been one of soft criticism and backroom manoeuvring: urging the Tsar to disavow this or that minister who had lost the confidence of ‘the people’, or to extend this or that democratic right.

At all times, the liberals were hoping to avoid what was now underway: a movement from below. They were alarmed by the increasing number of workers on the street.

Indeed, by 25 February, over 30 leaders of the working class had met in Petrograd at the Union of Workers’ Cooperatives to establish a soviet.

Soviets were workers’ councils: organs of proletarian democracy formed out of the strike wave during the 1905 revolution.

The liberals instead urged the Tsar, not to step down, but to replace more ministers!

Their cowardice stemmed from their class position. They understood how quickly revolutions can develop. They feared the masses may not stop at removing Tsarism, but could turn on them too: the factory and mill owners; the associates of French and British capital; the landowners.

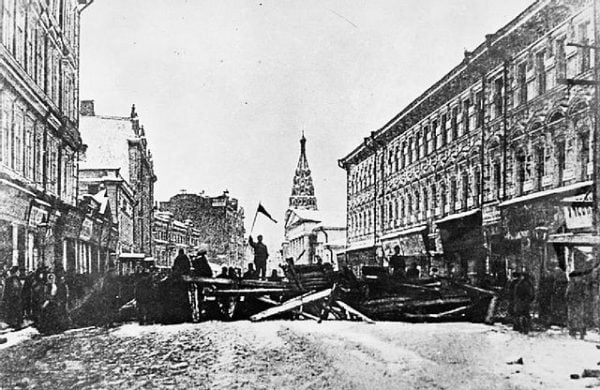

By 27 February, however, Petrograd was well and truly in the hands of the workers. This was despite the regime’s intentions to drown the revolution in blood the previous day, which failed as the troops joined the revolution.

It was clear the balance of forces had tipped decisively in favour of the working class. The Tauride Palace – the official meeting place of the Duma (parliament) – had already been taken by the workers and soldiers. In fact, it was in a wing of this prestigious building that the Petrograd soviet first met.

Conservative

With the writing on the wall, the bourgeois liberals switched tack. They moved to form a ‘provisional government’ made up of the capitalist parties. They desperately wanted to restore calm; to quell the revolutionary spirits circulating through the lower classes.

The Russian bourgeois were incapable of playing any progressive role. Inextricably tied to British and French capitalism on one hand, and woven with the large Tsarist bureaucracy and landowning class on the other, they were conservative before having even conquered power.

At the same time, they wished to modernise Russia, culturally and politically. They wanted greater say over the direction of the Russian economy, and stood for the freer development of capitalism. In other words, they wanted to have their cake, and to eat it too.

It was this that led Lenin to explain later that the bourgeoisie of Russia always attempted “to bring about the reform of the state on bourgeois reformist, not revolutionary lines”.

In fact, as Lenin knew, this was not unique to Russia. The bourgeoisie of all nations had long since ended its capacity for playing any kind of revolutionary role.

Debates

Which class would lead the revolution, and what the character of that revolution would be, had long been a key question for the Russian Marxist movement.

Before 1917, Lenin had long maintained the slogan of the ‘democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry’.

Lenin correctly understood capitalist property relations had triumphed in Russia. Nonetheless, there still remained strong remnants of feudalism.

The Tsar and nobility still retained power and owned much of the land on which the peasants toiled. The political tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution – land reform and the establishment of bourgeois-democratic rights – remained unfulfilled.

On this, there was no question within Russian Social Democracy that the coming revolution would be none other than bourgeois-democratic in character.

But from this understanding, and furnished by the experience of the 1905 revolution, in which the liberal bourgeois played a particularly cowardly role, Lenin proposed these tasks would only be fulfilled by the proletariat in alliance with the peasantry.

Lenin explained the bourgeoisie would attempt to hold back and even betray the revolution, as they were both tied to the Tsarist regime and afraid of the masses.

Conversely, the Mensheviks, insisted the role of Social Democracy in Russia was to aid the liberal bourgeoisie in completing its revolution, and then act as a kind of opposition within a new Russian bourgeois democracy.

Marx and Engels had always maintained the need for proletarian class independence. Lenin and the Bolsheviks maintained this consistent thread, while the Mensheviks and other opportunists attempted to break it.

Disorientated

For these reasons, the Mensheviks immediately supported the self-proclaimed Provisional Government in 1917, stating this alone could provide the basis for a “new, free Russia”. Along with the Social Revolutionaries (SRs), they commanded a majority in the new soviet executive, which in turn pledged support for the government.

This disarmed the vanguard of the working class who had taken power in Petrograd, and were distrustful of the Provisional Government – unsurprising, given it was led by a prince and contained many former Duma deputies! However, the Mensheviks commanded influence among many workers, and so their lead was followed, though uneasily.

With the majority of the Bolshevik leadership still in exile, meanwhile, the Bolshevik leaders inside Russia were hard-pressed with what position to take. The leaders that remained – such as Shlypanikov, Molotov, and Zalutsky – were capable organisers. They had kept the organisation together during a period of great repression. But they were not political thinkers.

As such, when the insurrection came, they were disorientated and unsure of what to do. The strikes by women workers on 23 February, for example, were not an initiative of the Bolsheviks. In fact, they had advised against the walkout! Only once they felt the momentum of events did they go along with it, trailing the movement from behind.

“We must lay it down as a general rule for those days that the higher the leaders, the further they lagged behind,” Trotsky remarked.

The arrival of other Bolshevik leaders, particularly that of Stalin and Kamenev, did not help matters either. In fact, their attitude to the Provisional Government was even worse. If Shlyapnikov and others were disoriented by the Provisional Government, Stalin and Kamenev were more confident in their call to support it!

Letters from afar

Lenin was the exception to the general rule outlined by Trotsky above. From exile in Switzerland, he grasped the significance of the situation and the development of dual power.

Aghast at the Bolshevik support for the Provisional Government, he began to send letter after letter to the editorial board of Pravda. These characterised the situation far better than the Bolsheviks within Petrograd itself.

“Side by side with this government, which as regards the present war is but the agent of the billion-dollar ‘firm’ ‘England and France’,” Lenin wrote in March, “there has arisen the chief, unofficial, as yet undeveloped and comparatively weak workers’ government which expresses the interests of the proletariat…the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies in Petrograd.”

Lenin was clear that the liberal bourgeois were not to be viewed as allies:

“Who are the proletariat’s allies in this revolution? It has two allies: first, the broad mass of the semi-proletarian and partly also of the small-peasant population, who number scores of millions and constitute the overwhelming majority of the population of Russia…

“Second, the ally of the Russian proletariat is the proletariat of all the belligerent countries and of all countries in general.”

Lenin put forward the idea that this was merely one stage in the revolution – and the next stage was to see the realisation of the power already held by the soviets.

Pravda’s editors admonished Lenin in its pages. Kamenev stated the “bourgeois-democratic revolution” had not been completed and Lenin was prematurely pushing for the “immediate transformation of this revolution into a socialist revolution”.

Plekhanov, once Lenin’s Marxist teacher, even referred to Lenin’s proposals as “anarchism”.

From all the way in New York, however, Trotsky also came to the same conclusions as Lenin.

Dual power

The Mensheviks strove to maintain their position at the head of the soviets, whilst supporting the government. But dual power is inherently unstable; only one class can rule society. Sooner or later, either the soviets would take power into their hands, or the bourgeoisie would crush them.

What’s more, while the Provisional Government ruled on paper, the soviets were the really viable force governing society. They were bona fide organs of administration,

springing up across Russia and intervening in the running of social affairs.

This was proven when, following an order from the Provisional Government that soldiers were to return to barracks and follow their officer’s orders, the soldiers instead used the soviet in which they were represented to make an official statement.

This laid out that soldiers were only to follow the orders of the government if they did not contradict the soviet; that all regiments should form committees and elect deputies to the soviet; and that weapons were to be controlled by these committees.

The armed bodies of men that all states rest upon were now falling under the authority of the soviets, not the Provisional Government.

It should be noted here, however, that the soviet executive, made up of Mensheviks and SRs, sought to stifle this order as much as possible.

Indeed, the reason this decree was even able to pass was due to the soviet leaders’ absence at the meeting – because they were negotiating with the liberals!

This encapsulates precisely the dynamics of dual power and the criminal irresponsibility of the so-called ‘socialist’ Mensheviks and SRs. As the workers and soldiers were asserting their will through their democratic organs, their leaders were discussing how to subordinate this alternative power to the bourgeoisie.

All power to the soviets

This state of affairs remained for some time. And as it did, all camps in society grew increasingly tired of the uneasy compromise between the classes.

In this time, Lenin raised the slogan of ‘all power to the soviets’ – a demand placed on the Menshevik and SR leaders of the soviets to break off support for the Provisional Government and seize control themselves.

Far from the bloodthirsty tyrant he is painted to be, Lenin constantly insisted that, were the soviet leaders to carry the revolution out in a decisive manner, there would have been an entirely peaceful transfer of power to the workers and peasants, who already ruled de facto through the soviets.

He raised this demand, despite the Bolsheviks not holding a majority in the soviets. He maintained a transfer of power to the soviets would have then entailed a democratic struggle for a majority within the soviets.

Eventually, the Bolsheviks were able to win a majority in the soviets, thanks to their patient explanation that the revolution had to be completed by the workers themselves, by taking power through the soviets.

The mistaken theoretical premise of the Mensheviks and SRs risked all that had been gained, leaving power in the hands of the liberal bourgeoisie, who had no qualms with drowning the revolution in blood.

Lessons

Lenin’s long-held principle of class independence, his distrust of the liberal Provisional Government, and his unshakeable faith in the potential power of the soviets, proved decisive.

Unfortunately, there have been many revolutions since in which such firmness on this question was lacking from the leadership of the working class.

This was especially the case with the Stalinists, who adopted the policy of the Popular Front. This advocated a unity between workers’ parties and the liberals, where the workers were subordinate.

This class-collaboration policy in Spain in the 1930s led to a terrible defeat, and prepared the way for the victory of fascism. In the words of Trotsky, the Popular Front acted as a “strike-breaking conspiracy”. In reality, it was a Menshevik policy.

In the total absence of a revolutionary policy, liberals with their vague democratic platitudes can come to power. But because they represent the interests of the capitalist class, they will only ever carry out policies in the interests of capitalism.

A recent example of this in the recent period is Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar – a bourgeois-liberal politician imprisoned by the military junta that ruled the country for decades. She was enormously popular because she was the only identifiable figure opposing the dictatorship.

But she came to power not through mobilising this support, but by means of a cynical deal that kept intact the power of the military junta. In turn, she supported and justified their genocidal campaign against the Muslim Rohingya people. Having been discredited, the junta found it all the more easy to remove her and resume their dictatorship.

Her path is emblematic of the bourgeois-liberal strategy in general: make deals at the top, and keep the class structure of society intact.

With revolutionary ferment developing all across the globe, it is vital that the experience of the February Revolution is learnt, and that the firmness of Lenin on class independence is absorbed.

The only solution to the problems the working class faces is the abolition of the capitalist system. And this can only be achieved when the workers take power for themselves.