We live in a period of constitutional crises, of which Brexit is a prime example. Donald Trump’s conflicts with his own national security services, and the movement for Catalan separatism, are also displays of dramatic political crises.

Internationally, we are seeing the rise of ‘illiberal democracies’ in Hungary, Poland, Turkey and Russia. And alongside that, we see the rise of their admirers in the Austrian Freedom Party, the Italian League, the Alternative for Germany, Le Pen’s National Rally in France and the new Brexit Party in Britain.

Protectionism and trade wars are being ramped up, victory of the Brexit Party at the European elections. Liberalised world trade is under threat. And from another ideological direction, Corbyn in Britain is promising large-scale nationalisations, undermining the ‘free’ market, and achieving enormous popularity as a result.

For the ruling class this is a disaster. It’s finding that it can’t rule society with the ideas of liberalism any longer. Newspapers like The Guardian and The Economist are filled with self-pitying editorials and opinion pieces bemoaning the rejection of liberalism.

The victory of the Brexit Party at the European elections has sent the liberals into a frenzy. The likely election of a ‘populist’ hard Brexiter as leader of the Tory party – and therefore as Prime Minister – is a liberal nightmare.

While liberals teeter on the brink of despair, Marxists are increasingly optimistic. The crisis of liberalism is caused by people looking for an alternative to the status-quo, which cannot deliver improvements in people’s lives anymore. We have an alternative: the socialist transformation of society.

What is liberalism?

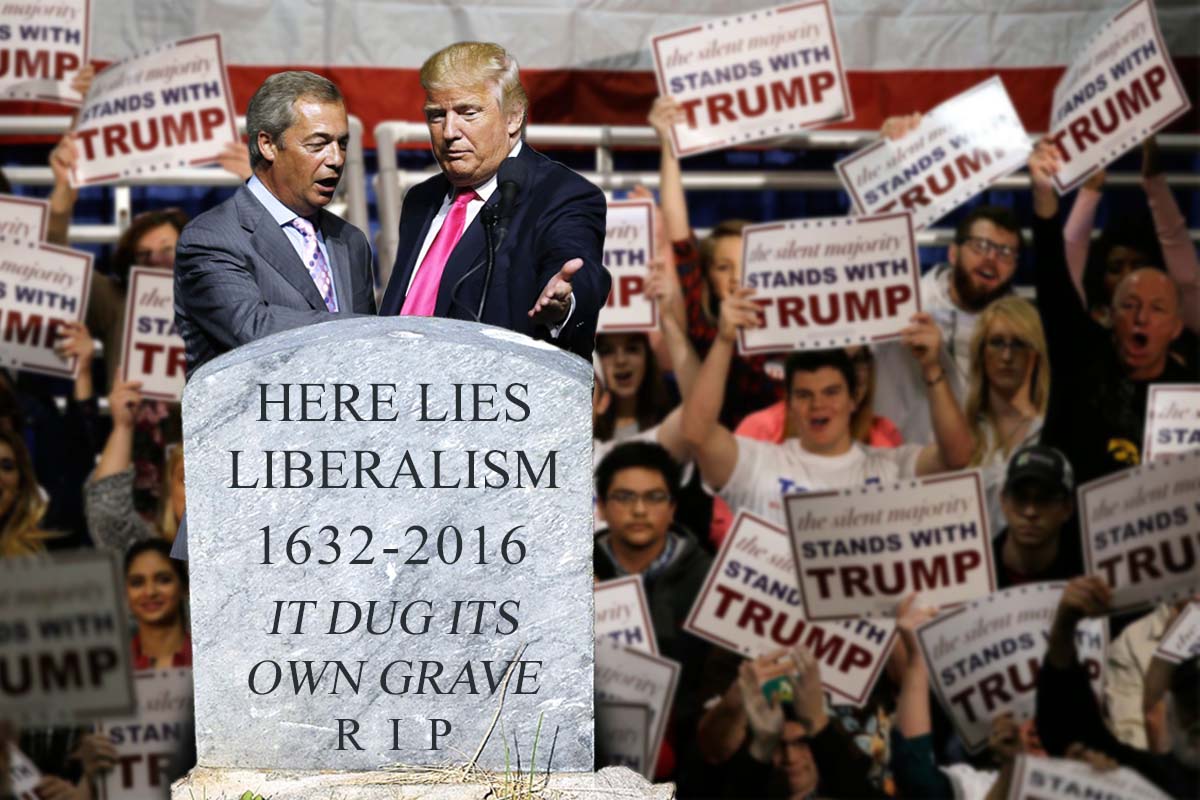

Liberalism is the philosophy of capitalism and imperialism. That’s why Marxists oppose it. But we’re also opposed to right-wingers like Donald Trump who are trying to profit off the crisis of liberalism using racism, xenophobia and other means to divide working class people against each other. We want to bury liberalism, not with right-wing demagoguery but with socialism.

Liberalism is notoriously difficult to define. Generally speaking, liberal ideas centre on the championing of the individual, free markets, universal suffrage, the rule of law, constitutional government, civil society, etc.

These ideas arose at the time of the bourgeois revolutions, such as the English Civil War of the 17th century and the French Revolution of 1789. These revolutions erupted over questions such as the right to certain forms of religious worship; or against the imposition of heavy taxes by tyrannical monarchs. But unconsciously they expressed the rebellion of the bourgeoisie, and the rising capitalist economic system that they represented, against the outmoded, suffocating feudal regime.

Feudalism had become a brake on economic development. Serfs were tied to the land, unable to move freely. And their loyalty had to be to one particular lord. They were not individually free.

But a rising merchant class, the new capitalist class, wanted the ability to move freely from place to place in order to trade. They wanted guarantees that taxes and laws wouldn’t change arbitrarily from one lord’s fiefdom to the next. This was the only way the merchants would be able to expand and develop the economy. But it brought them into conflict with the feudal lords, whose power and position it challenged.

To develop the forces of economic production a fundamental transformation of society was required. This was the bourgeois revolution, led by the merchant class against the aristocracy. It was carried out with slogans of individual liberty and centralised, constitutional government for each nation state. Liberalism was the philosophy of the new capitalist society it created.

The revolutionary capitalist class was a small layer in society, which sought to replace the aristocracy as the ruling class. To carry through a successful revolution, this small layer needed to ally itself with the masses. But the masses would never have got behind a movement whose explicit aim was simply to replace one type of ruling class with another, because there’d be nothing in it for them.

And so, the liberal philosophy promoted by the rising capitalist class was deliberately abstract and hard to define. That way, anyone could fill it with whatever meaning they wanted and an alliance between classes could be built.

For the capitalist class the slogan of the French Revolution, ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity’, meant giving everyone the liberty to choose who their exploiters were, and formal legal equality (as long as you were a man and owned property). But for the working class it meant economic equality and getting rid of the exploiters altogether.

Both interpretations were possible because of how vague the slogan was. The emptiness of liberal ideas is central to their primary role in capitalist society – building support for the capitalist system among classes with opposite interests.

The vagueness of liberal ideas was enough to overthrow feudalism. But class conflict between the working and capitalist classes inevitably followed soon after. As the French Revolution progressed, the plebeian sans-culottes came into conflict with the bourgeois Girondists.

Later, in 1848, Europe was swept by a new wave of revolutions. These revolutions were principally directed against the remnants of feudalism. But at their high point, in June 1848, the working class of Paris staged its own uprising, sending a shiver down the spine of the French capitalist class.

Once the working class realised that its interests were not aligned with those of the new ruling class, the capitalist class, it began developing its own political philosophy. These were the ideas of socialism.

The death of liberalism

Today, liberalism is in a deep crisis. The political crises affecting countries all over the world are not the usual scandals that can be resolved by sacking this or that government minister or official. They reach much deeper into the foundations of bourgeois society.

Today, liberalism is in a deep crisis. The political crises affecting countries all over the world are not the usual scandals that can be resolved by sacking this or that government minister or official. They reach much deeper into the foundations of bourgeois society.

Scottish nationalism, Catalan separatism, and the impact of Brexit on Ireland, all threaten the territorial integrity of long-established nation states. Centralised states formed by capitalism generations ago are now being questioned.

The independence of the judiciary and the separation of powers has been dragged through the mud in the USA, Brazil and Poland in recent years. This is the mechanism by which the capitalists ensure that individuals can be rotated in and out of government – by ‘holding them to account’ – while preserving the overall structure of class society. Now it seems to be breaking down.

Most worryingly for the liberals, the sober-minded political representatives of the capitalist class are being sidelined and humiliated in one country after another. In France, for the first time since 1958, neither of the mainstream Socialist or Republican parties made it to the second round of the 2017 presidential election.

Emmanuel Macron, who won that election on a liberal platform, has since provoked the movement of the Yellow Vests, to which he was forced to capitulate on a number of economic demands. Two-thirds of people polled in May 2019 think he is doing a bad job as president.

The Italian elections in 2018 were another example, in which two ‘anti-establishment’ and anti-EU parties won and formed a government. The traditional and ‘safe’ representatives of Italian capitalism have been marginalised.

The victory of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016, despite the opposition of the entire mass media, was another example of a sober representative of capitalism losing out to a loose cannon. The spectre of Boris Johnson that hangs over the Tory Party, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party, and the withering of the Blairite splinter group – The Independent Group – are all similar cases.

These are not normal political crises – the system as a whole is breaking down. Why?

Contradictions of liberalism

Liberalism as a philosophy is based on individualism. This was its weapon against feudalism.

But this contradicts the basis of the capitalist economic system. Capitalism doesn’t function in an individualistic way – it relies on the division of society into classes. Under capitalism a person’s role in economic production is not an individual question but determined by whether that person owns the means of production, and is therefore a capitalist, or works for a wage and is therefore a worker.

At different times this class contradiction upon which capitalism is based becomes sharper or less clear. In periods of economic crisis, such as now, the class contradictions come into sharp relief.

Today, capitalism can no longer deliver improvements in most people’s standard of living. The young generation today are the first since the Second World War to face a worse standard of living than that of their parents. Housing, education and healthcare are all in a state of crisis. Insecure work and low pay riddle the economy. And all the while, the rich get richer while the rest of us get poorer.

When this kind of crisis happens, which is inevitable under capitalism, it becomes clear that individual freedom is entirely subordinate to and dictated by a person’s position in relation to the means of production.

It’s obvious now that the rich aren’t rich because they work harder but because of their class position. Some of the people who work the hardest today are the ones who are forced to work two or three jobs just to keep a roof over their head, and whose housing benefits have been frozen for almost a decade. Some of the richest people are the ones who lounge around on super-yachts and live lives of luxury.

Likewise, the basic democratic right of universal suffrage is superseded by the fact that the bosses and the bankers, who own the means of production, take all the real decisions under capitalism.

In 2015, the working class of Greece elected SYRIZA into government on an anti-austerity manifesto. However, within six months this government had reneged on its manifesto and, after bullying and threats, agreed to implement the diktats of the bankers and big business. Class conflict is what decided the policies of that government, not liberal democratic rights.

Even the rule of law becomes seen, not as something that can protect people, but as something that protects the ruling class alone. There’s no human right to a house or a job, for example, but there is a legal right to private property. So, we end up with thousands of privately-owned empty houses (used as vehicles for speculation) side-by-side with thousands of homeless people outside in the streets. Class interests today come before liberal concepts of natural justice.

When capitalism is in crisis, a struggle between the ruling class and the working class opens up to determine who is going to pay for the crisis. When this class struggle bursts to the surface the hollowness of liberalism, as a philosophy attempting to unite the opposing classes, becomes clear.

The recent elections in South Africa are one example of this. Just one generation after the working class ended apartheid and conquered the right to vote, in what was supposed to be a triumph of liberalism, 51.5% of people didn’t participate in the elections. This isn’t due to political apathy, but disillusionment with the status quo.

While election turnout was the lowest ever, protest movements have reached record high levels every year since 2013, and student movements have hit new peaks every year since 2015. In South Africa, class struggle is coming to the fore and, as a result, illusions in liberal democracy are crumbling.

The right-wing ‘anti-establishment’

However, this process of rising class struggle and the undermining of liberalism isn’t always a conscious one. The fundamental contradictions in capitalist society cause a questioning of the status quo, which for many quickly becomes a lashing out. But this isn’t automatically on the basis of a class understanding of society. This is what allows the right wing to hijack the crisis of liberalism.

However, this process of rising class struggle and the undermining of liberalism isn’t always a conscious one. The fundamental contradictions in capitalist society cause a questioning of the status quo, which for many quickly becomes a lashing out. But this isn’t automatically on the basis of a class understanding of society. This is what allows the right wing to hijack the crisis of liberalism.

Nationalists and racists all reject liberalism and tap into a collective identity. They blame one part of the working class and try to get the rest to mobilise against them. This is the logic of Trump’s attacks on Muslims, the Brexiters’ attacks on migrants, and so on.

This pits them against the ‘liberal establishment’ who defend liberalism as the best possible political shell for preserving capitalism. Thus, Donald Trump and Nigel Farage acquire an ‘anti-establishment’ image, which further chimes with the mood in society.

These people opportunistically use the crisis of capitalism and liberalism. But they divert it away from the main division in society that causes a crisis in the first place: class division. This serves, in the final analysis, to protect the establishment and the capitalist system by diverting the movement into safe channels that won’t threaten the property or profits of the 1%.

Fight the far right and the liberals

It’s the role of the labour movement to expose these right-wingers as defenders of the status-quo. Where the establishment use liberalism, Trump and Farage use racism and nationalism. But in both cases the end result is the same – working class people are exploited for the profits of the rich.

It’s the role of the labour movement to expose these right-wingers as defenders of the status-quo. Where the establishment use liberalism, Trump and Farage use racism and nationalism. But in both cases the end result is the same – working class people are exploited for the profits of the rich.

We must ensure that, in opposing the far right, we don’t find ourselves defending the liberal establishment whose contradictory philosophy and capitalist economic system has given rise to the crisis facing millions of people around the world today. The labour movement needs an independent, working-class banner which fights both liberalism and the far-right with socialism.

Liberalism is not in crisis due to the mistakes or incompetence of the liberals. It is in a mess because the organic crisis of capitalism inevitably leads to class struggle. Under the piercing gaze of class-conscious workers, the empty ideas of liberalism wither into nothing.

This means that we shouldn’t be looking to ally ourselves with the liberals, or try to rescue their decrepit pro-capitalist philosophy. Hillary Clinton would not have been an effective antidote to Donald Trump – in fact she would have fuelled his politics by promoting the contradictory liberal defence of the capitalist system which is discredited in the eyes of millions of people.

Figures like Yanis Varoufakis, the former finance minister of Greece, pose as left-wingers seeking to save liberal values from the bungling liberals. But, as explained, liberal values are based on an unsustainable contradiction. The capitalist crisis in Greece laid bare this contradiction.

Instead of mobilising the Greek masses for a struggle against capitalism, Varoufakis based himself on ‘game theory’ and tried to make the EU ‘see sense’. But the EU was acting very much in the interests of European capital in punishing Greece. After the inevitable failure of his strategy, Varoufakis was able to resign as finance minister and tour Europe charging large sums for speaking engagements. The Greek masses had no such safety net.

Those who are willfully blind to the realities of capitalism and the class struggle, who hide behind the contradictions of liberalism, always end up siding with the establishment and the status quo. The austerity-imposing Liberal Democrat coalition with the Conservatives in 2010 is a stark reminder of this fact.

The pressure of ‘lesser-evilism’ must therefore be resisted. Voting for Macron against Le Pen, or for Clinton against Trump, is no solution to the crisis of capitalism. You don’t put out the fire by voting for the arsonist. The road of liberalism leads only into the quicksand of the political centre ground, while allowing the far right more time and ammunition with which to build their forces.

Liberalism is the philosophy of the ruling capitalist class. We must counterpose it with a philosophy of the working class.

Our ideas must be based on a study of the history and theory of the working-class’ struggle. These are the ideas of Marxism. Where liberalism is deliberately ill-defined to facilitate class collaboration, Marxism must be unequivocal in what it stands for. Unlike liberals, we are not in the business of deceiving the masses but winning them over to clear socialist policies and ideas.

What next?

With capitalism in crisis, those who cling to the liberal centre ground are doomed to go down with the sinking capitalist ship. Society is polarising. The working class will look to the left, because it’s conditions are based on cooperation and solidarity. But where the left fails to raise an independent working-class banner and to fight for socialism, the way will be clear for far-right demagogues to spread their poison. The future is one of socialism or barbarism.

With capitalism in crisis, those who cling to the liberal centre ground are doomed to go down with the sinking capitalist ship. Society is polarising. The working class will look to the left, because it’s conditions are based on cooperation and solidarity. But where the left fails to raise an independent working-class banner and to fight for socialism, the way will be clear for far-right demagogues to spread their poison. The future is one of socialism or barbarism.

The job of Marxists is to make conscious what is unconscious in people’s minds. We can illuminate and explain the process of questioning and lashing out that the crisis of capitalism and liberalism brings. By making this a conscious process we can prevent it being diverted down reactionary right-wing, racist and nationalist lines. Instead we can direct it at the real enemy – the capitalist class.

On that basis we can resolve the contradictions that have given birth to the crisis of liberalism. And achieve the socialist transformation of society.