The western press has celebrated Russia’s retreat from Kherson in Ukraine. But this withdrawal does not represent a decisive defeat for Putin. The outcome of the war still hangs in the balance, as economic, social, and political tensions mount.

When Russia’s defence minister appeared on state media to report that he had ordered a withdrawal from the west bank of the Dnipro River, including from the city of Kherson situated on the east bank, the news was immediately hailed by the western media as a great victory for the Ukrainian army.

This jubilation was something everyone could understand. Kherson was the only major Ukrainian regional capital city to be occupied by the Russians since the start of the war last February. Recapturing it and pushing the Russians out of the west bank of the river would therefore have immense symbolic and logistical value for Ukraine.

It would also be a colossal setback for Russia, which needs the area to secure a water supply to Crimea. For those reasons, they had every incentive to defend it.

For Vladimir Putin, the loss of Kherson was obviously a most embarrassing setback. He had presided over a ridiculously ostentatious ceremony in the Kremlin, striking the studied pose of a nineteenth century Tsar to celebrate the annexation of Kherson and the other three oblasts.

He was televised signing a document that proclaimed the newly conquered territories were now an inalienable part of the Russian Federation. And he declared to the whole world that: “We will defend our land with all the powers and means at our disposal.”

Now, only a few weeks later, he is publicly humiliated by the surrender of Kherson. What better news could there be for the Kyiv government and its western backers?

One might have expected an explosion of popular joy and euphoria, accompanied by the sound of trumpets and drums, military parades and defiant speeches from Zelensky announcing new, even more spectacular advances and the imminent defeat of Russia.

Instead, to the world’s astonishment, Zelensky warned against an excessively triumphant interpretation of this development, which he said may be only a move to regroup forces. In the immortal words of Alice in Wonderland: curiouser and curiouser.

Bonapartist regime

How is it possible to make sense of all this?

To start with, in this life, not everything is as it seems to be. It is one thing for Putin to make grandiose declarations in the Kremlin, or for Zelensky to make stirring speeches to the adoring dignitaries of foreign parliaments.

But the practical conduct of the war is in the hands of local commanders, whose most pressing need is to deal with the realities of the situation on the ground and to take the appropriate decisions.

The Ukraine war is a reflection of the inherent weakness of a bourgeois Bonapartist regime. One can say that, so far, on the Russian side, it has been a war in which political factors have played a far greater role than purely military ones.

From the beginning, the driving force has been, on the one hand, NATO’s aggressive push towards Russia’s borders; on the other, the exaggerated ambitions of Vladimir Putin and his desire to enhance his personal prestige and his grip on power, which is closely related to it.

The desire to confront the aggressive expansion of NATO – that is, fundamentally, US imperialism – is an aim that can be understood and enjoys widespread support amongst the Russian people, in particular, the working class.

But the Bonapartist nature of the regime stands in the way of a successful military campaign. Putin’s personal interference in military decisions played a negative role from the beginning, when he clearly underestimated the dimensions of the problem that he had set out to resolve by the only means he knows – violent force.

Putin is the product of capitalist restoration in Russia. He poses as a strongman, but in reality he is the creature of a corrupt and rapacious class of oligarchs who have enriched themselves through the massive theft of state property, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Corruption is rife in such a system. It is built into its DNA and is its heart and soul. It penetrates all layers of society, from the very top to the bottom. And since any army is only the mirror image of the society that created it, the same corruption will be found there also.

It is impossible to have an accurate idea of the scale of corruption, robbery, theft, nepotism, favouritism, bullying, bungling, and inefficiency that exists in Russia’s army. There can be little doubt that such factors as these have played a significant role in the failures of the Russian army in the Ukrainian campaign.

A series of embarrassing reversals highlighted serious weaknesses on the Russian side. It has also damaged the personal prestige of Vladimir Putin – potentially a serious problem for the ‘Strong Man’ in the Kremlin.

It was this that finally persuaded him that it was necessary to take a step back and leave important tactical issues related to the running of the war more in the hands of commanders of proven worth who are in direct contact with the realities of the battlefield.

This, together with the long-delayed order to mobilise new forces for the front, might represent a significant change for the better in Russia’s fortunes.

General Surovikin

Enter General Sergei Surovikin, who was put in charge of Russian forces in Ukraine on 8 October after the terrorist attack that damaged a strategically important bridge that connected Russia to Crimea. He has been given a bad press in the West, which portrays him as a ruthless man with a reputation for brutality and for bombing civilians in Russia’s campaign in Syria.

They conveniently forget the brutal American bombing that reduced Mosul to a pile of smoking rubble. They also forget to add that Surovikin’s Syria campaign was also highly successful. That fact, and not any moral considerations, explains their extreme dislike of the man.

It is necessary to approach war in its own terms, just as one must approach art, science, or any other subject in its own terms, since what is applicable and appropriate for one is wholly inapplicable and inappropriate to another.

Humanitarianism and the desire to prevent human suffering are, of course, highly praiseworthy. These values are very important, for example, for nursing. But a heavyweight boxer who placed such considerations high on his list of priorities would not win many fights.

By the same token, a general whose main interest was in saving lives would not win many wars, since wars are, by definition, about killing people. Sad to say, it is precisely the most ruthless generals who are likely to win battles. And we must judge Surovikin, just as we would judge a professional in any other field: solely by the results he achieves.

Obviously, the Russian decision to withdraw its troops to the eastern bank of the Dnipro River was of considerable propaganda value for Ukraine and its western backers. But wars are not won or lost on the basis of propaganda. And from a military point of view, it actually made perfectly good sense for the Russians to do just what they have done.

The western media have made a lot of noise to the effect that the delivery of modern ‘smart’ weapons to Ukraine represent a ‘game-changer’. That is an exaggeration. HIMARS and other advanced weapons systems in and of themselves are not enough to tip the overall balance of forces.

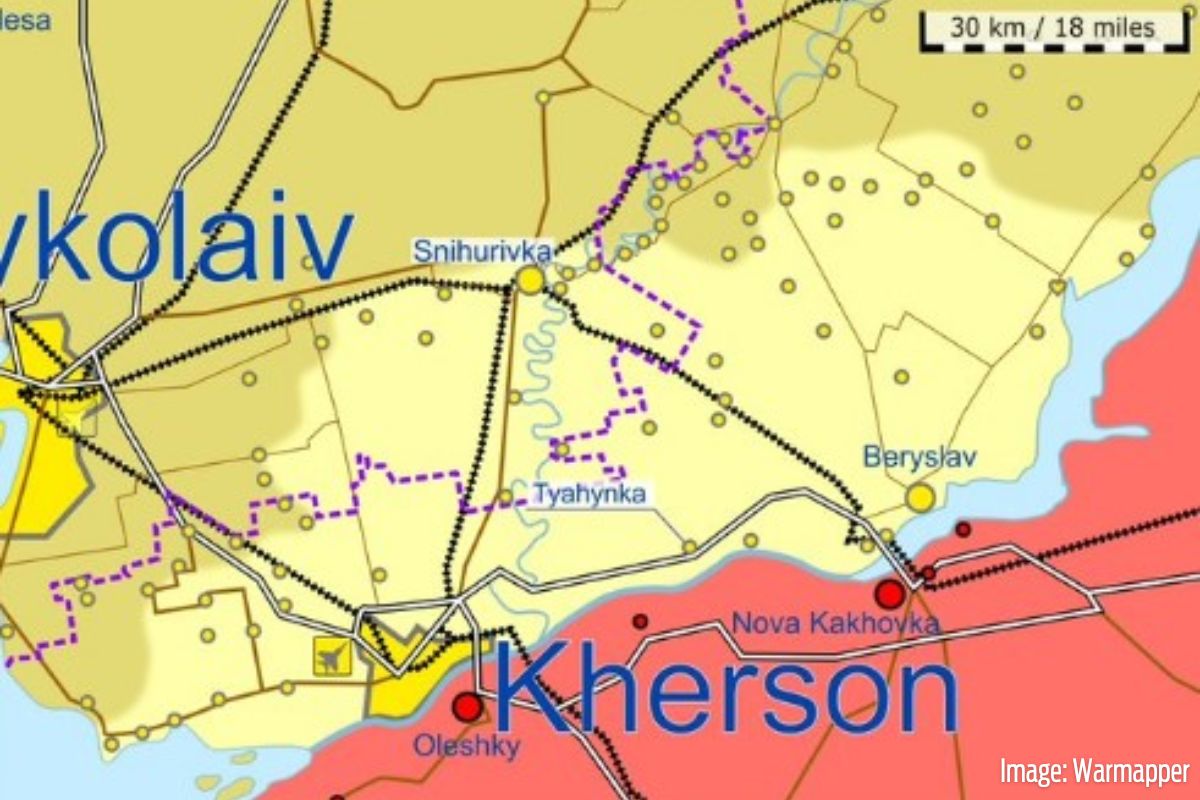

Nevertheless, they were sufficient to create a lot of problems in the Russian rear, weakening their supply lines. In particular, the supply of advanced artillery pieces to the Ukrainians by the West before the summer allowed them to destroy the bridges over the Dnipro and created serious difficulties for keeping the defenders of Kherson supplied with food and ammunition.

The Ukrainians were advancing on two fronts towards Kherson, threatening to surround the city and effectively cut off its garrison, which would be faced with the alternative of surrendering or being cut to pieces. That indeed would have represented a major defeat for Russia.

Faced with that possibility, Surovikin decided that it was best to preserve the Russian forces and equipment by withdrawing to the east bank of the river, which forms a natural defensive line.

The fall of Kherson was not achieved by a heroic assault by the Ukrainian army. Indeed, battlefield reports from the BBC on Ukraine’s side of the Kherson frontline indicated that Kyiv’s forces might still lack the necessary equipment to achieve that aim.

So, when reports began to circulate that the Russian forces would probably leave the city and withdraw to the eastern bank of the Dnipro river, they were not taken seriously.

In fact, the first reaction was incredulity. Was this just a trick? Are they trying to lure us into an ambush? The spokesperson for Ukraine’s southern command, Natalia Humeniuk, described it as a ruse to draw Ukraine into battle.

Even so, it seems hard to explain the extraordinary degree of caution with which the news of the Russian withdrawal has been met on the Ukrainian side. And there are other things that are even harder to explain.

Why was there hardly any fighting around Kherson? Why was the capital city taken with hardly a shot being fired? More importantly, why were the withdrawing Russian forces not subjected to a merciless bombardment?

Tens of thousands of Russian troops crossing across the Dnipro through a small number of pontoon bridges would have been like sitting ducks for Ukrainian artillery and drones. Yet the withdrawal was carried out in good order and seemingly without significant loss of life.

Was there a deal?

Now the Ukrainians are belatedly trying their best to make this sound like a great victory. But reading between the lines (which one always had to do in this war), it is becoming clearer that the situation was not all that it seemed to be.

There are only two alternatives. Either the Ukrainian commanders are deaf, blind, dumb, and very stupid (which we do not believe). Or else they had reached some kind of deal with the Russians. They would be allowed to take the city of Kherson without a bloody battle, on condition that they allowed the Russians free passage to the eastern shore with the bulk of their forces intact.

Such a suggestion may seem to come straight out of the cyberworld of the craziest conspiracy theories. But any student of military history will know that it has plenty of historical antecedents.

In the 18th century, there was no such thing as standing armies or conscription. The armies of the absolute monarchs of Europe were largely made up of mercenaries, recruited from different countries who fought for their pay. That meant that wars were a very expensive business.

In order to reduce the losses caused by deaths that all too often occur on battlefields, they invented the most ingenious schemes. On the eve of a battle, the two opposing generals would meet like proper gentlemen and discuss the disposition of their armies.

Following the accepted rules of warfare, as one would study a chess board, they would conclude that one side clearly had the advantage and therefore would be entitled to declare victory. The other side would gracefully concur and the whole matter would be settled amicably, without the expense and unpleasantness of fighting.

These methods were finally shattered by the French Revolution, which fought wars by revolutionary means, mobilising the entire male population through what was called the levée en masse (mass levy).

The mass of raw soldiers went into battle without any of the necessary military training, but fired by the ideals of the Revolution. These bare-footed sans-culottes threw themselves against the professional soldiers with no fear of losing their lives. The armies of Austria and Prussia had never seen anything like it and fled in terror. Such is the power of the revolutionary people.

The French Revolution changed the face of Europe in many ways. It also changed the nature of war itself. Beginning with Prussia, every European state was compelled to introduce conscription, following the French example, but of course, without any of its revolutionary content. The new way of war was seen in all its bloody reality in two world wars. But the Kherson business suggests that the old ways of the 18th century have not died out altogether…

General Surovikin took one look at the map and immediately grasped the fact that, once the bridges across the Dnipro were down, the only real possibility open to him was to withdraw from a place that could not be supplied and retreat to the safety of the east bank.

The successful movement of several thousand Russian troops across the Dnipro without significant loss of life or equipment provides powerful confirmation to the Russian version that the withdrawal from Kherson city was a tactical manoeuvre, aimed at avoiding a catastrophic defeat.

This decision was forced upon them by the unfavourable circumstances already commented on. But it is the duty of a commander in the field to take account of such changes and act accordingly, which is what Surovikin did. There was absolutely nothing reprehensible about it from a strictly military point of view.

The complaints from the ultra-nationalist wing in Moscow merely show how far removed these gentlemen are from the realities of war. Even more ridiculous were the statements made by Medvedev and others to the effect that ‘nothing has changed’ and Kherson remains within Russia.

That is clearly false. From the point of view of the Russian campaign, the value of the bridgehead on the west bank of the Dnipro was mainly as an advance position for an offensive on Mykolayiv and Odessa. Those plans have now been abandoned for the foreseeable future and any attempt to cross the river again will be much more difficult.

Putin showed more sense than the others when he simply kept silent and slid quietly into the shadows, on the very sound principle that it is better to keep your mouth shut and let people think you are a fool than open it and let them know you are a fool.

In any case, the loss of Kherson is far from the end of the story and even if it causes some embarrassment to Putin, it will not do him any lasting damage.

The West is constantly harping on the theme of the imminent overthrow of Putin. But most people in Russia – especially the working class – believe (correctly) that this is a war of Russia against NATO, and their hatred of US imperialism far outweighs any other consideration.

They will therefore continue to support Russia’s war and to tolerate Putin’s leadership – until that becomes absolutely untenable. But that moment has not yet arrived.

What has been achieved?

The question has to be asked: what has been achieved by the Russian withdrawal from Kherson?

The Ukrainian army has been left in control of a largely deserted city, presumably full of mines and booby traps, while the Russian forces, by withdrawing to the other side of the Dnipro, have placed themselves in a strong defensive position.

The river Dnipro is itself a formidable barrier, which bars the eastward thrust of the Ukrainian forces. The surrounding area is mostly open ground with little or no cover for advancing troops to shelter from enemy fire. And the Russians have had plenty of time to fortify the eastern bank with concrete bunkers.

This means that the Ukrainians now have no realistic prospect of any further advance on the southern front. True, having come up to the Dnipro means that the supply lines into Crimea are now within the range of their artillery in the west bank. And true, they now have more troops which can be deployed elsewhere on the frontline.

There are reports that they are moving them to the Zaporizhzhia front where they might attempt to cut the Russian land corridor. It is impossible to verify these reports. But the Russians will also now have more troops free to defend the front wherever necessary.

The numbers of Russian soldiers mobilised continues to grow. And as winter grows closer, the frozen ground will make it possible to move their tanks into action. There is talk of a Russian winter offensive, which may not materialise. But it cannot be excluded.

Meanwhile, constant air bombardment is destroying the Ukrainian infrastructure to the point that there is even talk of evacuating major cities – including Kiev – which the constant degradation of the infrastructure threatens to render uninhabitable.

Washington’s response

The reality of the situation is not lost on serious military strategists in Washington. Speaking at an event at The Economic Club of New York, Joint Chiefs Chair general Mark Milley commented on the withdrawal of up to 30,000 Russian troops from the west bank of the Dnipro:

“I believe they’re doing it in order to preserve their force, to re-establish defensive lines south of the river, but that remains to be seen.”

But Milley emphasised something else. He insisted that:

“[T]here may be a chance to negotiate an end to the conflict if and when the front lines stabilise during winter. When there’s an opportunity to negotiate, when peace can be achieved, seize it. Seize the moment.”

The general’s enthusiasm for negotiations is no accident. It arises from his sober-minded appraisal of the real balance of forces:

“There has to be a mutual recognition that military victory is probably in the true sense of the word may be not achievable through military means, and therefore you need to turn to other means,” he said.

This is the authentic voice of US imperialism. And this, not the rhetorical declarations of Zelensky, is what ultimately determines the fate of Ukraine.

In an even more significant development, The Wall Street Journal revealed that the Biden administration has refused to give Ukraine advanced drones that could target positions inside Russia.

The decision deprives Ukraine of the kind of advanced weaponry Kyiv has been requesting for months. Despite pleas from Kyiv and a bipartisan group of members of Congress, the Pentagon declined the request to provide the Gray Eagle MQ-1C drones which could negatively affect the extensive use by Russia of Iranian drones.

This was a clear reflection of the limit of the kinds of weaponry Washington is willing to provide for Ukraine’s defence. It was intended to send a signal to Moscow that the U.S. was unwilling to provide weapons that could escalate the conflict, creating the potential for a direct military conflict between Russia and NATO.

It was also a warning to Zelensky that there were definite limits to the willingness of the US to continue to foot the bill for a ruinously expensive war with no clear end in sight.

In an interview with CNN, the Ukrainian President appealed for continued bipartisan support following the midterm elections. He is clearly a worried man and his worries are well founded.

“Politics by other means”

Clausewitz pointed out long ago that war is only the continuation of politics by other means. The present war will end when the political ends of the key players are satisfied, or when one or both sides are exhausted and lose the will to continue fighting.

What are these goals? The war aims of Zelensky are no secret. He will, he says, settle for nothing less than the complete expulsion of the Russian army from all Ukrainian lands – including Crimea.

He has said he will refuse to negotiate with Vladimir Putin. He even signed a decree specifying that Ukraine would only negotiate with a Russian president who has succeeded Putin. But that assumes – rather optimistically – that there is someone else he could negotiate with.

This standpoint is enthusiastically supported by the hawks in the western coalition: the Poles; the leaders of the Baltic States, who have their own interests in mind; and, of course, the wooden-headed chauvinists and warmongers in London, who imagine that Britain, even in its present state of economic, political, and moral bankruptcy, is still an imperial power.

These deranged ladies and gentlemen are pushing the Ukrainians to go further – much further than the Americans would like. Their most ardent desire is to see the Ukrainian army driving the Russians, not just from Donbas, but also Crimea, provoking the overthrow of Putin and the total defeat and (though they do not often speak of this in public) the complete dismemberment of the Russian Federation.

But the more sober-minded strategists of US imperialism know that all this delirium is just so much hot air, like the bullfrog in Aesop’s fable, who blew himself up to the point where he simply exploded. It is the stuff of dreams and has absolutely nothing in common with the real world.

Although they make a lot of noise, no serious person pays the slightest attention to the antics of the politicians in London, Warsaw, and Vilnius. As leaders of pygmy states that lack any real weight in the scales of international politics, they remain second-rate actors who can never play more than a minor supporting role in this great drama.

In fact, all the noise they make is merely an annoying distraction for US imperialism, for it is the USA that pays the bills and dictates everything that happens.

The war aims of US imperialism

In reality, the war aims of Washington do not coincide with those of the men in Kyiv, who long ago surrendered their so-called national sovereignty to their Boss on the other side of the Atlantic, and who no longer decide anything.

The goal of US imperialism is not – and never has been – to defend a single inch of Ukrainian territory or help the Ukrainians win a war, or in any other way.

Their real aim is very simple: to weaken Russia militarily and economically; to bleed it dry and to inflict harm on it; to kill its soldiers and ruin its economy, so that Russia will no longer offer any resistance to American domination of Europe and the world.

It was this aim that induced them to push the Ukrainians into an entirely unnecessary conflict with Russia over NATO membership. Having achieved this aim, they sat back and watched the spectacle of the two sides slugging it out, at a safe distance of several thousand miles.

They are entirely indifferent to the sufferings of the people of Ukraine, who they regard as mere pawns on the local chessboard of their power struggle with Russia. And it must be noted that, up to the present day, Ukraine has not been admitted to NATO membership, which was supposed to be the central business in the whole affair.

This is no accident. The present conflict suits America’s interests in many ways. They have the luxury of embroiling their enemy in a war in which no American soldiers are involved (at least, in theory), and all the fighting and dying is obligingly carried out by others.

If Ukraine was a member of NATO, this would mean that American combat troops would end up in a European war, fighting the Russian army, which possesses nuclear weapons. No. Far better to leave things as they are.

When Zelensky complains that his western allies are not sending him all the arms he needs to win the war, he is not wrong. The Americans are sending him just enough arms to keep the war going, but not enough to score anything that resembles a decisive victory that could escalate into a direct conflict between Russia and NATO. But this is completely in line with America’s war aims.

Sanctions have failed

One important factor is the effects of the war on the world economy and the threat to social and political stability in the West that derives from it.

The sanctions imposed on Russia after it invaded Ukraine have been a spectacular failure. In fact, the value of Russian exports actually grew since the start of the war.

Although the volume of Russia’s imports plunged as a result of sanctions, a number of countries have increased their trade with Russia. According to a detailed study by The New York Times imports from Turkey have increased by 113 percent, and Chinese imports by 24 percent.

The volume of trade with Russia after the start of the war was as follows:

Britain: -76%

Sweden: -76%

USA: -35%

Germany: -3%

Japan: +13%

South Korea: +17%

Netherlands: +32%

Spain: +57%

China: +64%

Belgium: +81%

Brazil: +106%

Turkey: +198%

India: + 310%

Moreover, the high prices of oil and gas have offset revenue that Russia lost to sanctions. India and China have been buying much more of its crude, albeit at a discounted rate.

Thus, the lost income resulting from sanctions has been compensated by the rising price of oil and gas on world markets. Vladimir Putin continues to finance his armies with the proceeds, while the West is faced with the prospect of a freezing winter with soaring energy bills and rising public anger.

Support weakening

The question is: which side will tire of the war first? It is clear that time is not on the side of Ukraine, either from a military or a political point of view. And in the final analysis, the latter will weigh most heavily in the scales.

As winter sets in and Europe is hit by a serious shortage of gas and electricity, public support for the war in Ukraine will weaken.

Nor can US support be taken for granted. In public, the Americans are keeping up the idea of their unshakable support for Ukraine, but in private, they are not at all convinced about the outcome.

Behind the scenes, Washington has been putting pressure on Zelensky to negotiate with Putin. That was shown by Blinken’s surprise visit to Kyiv in September, and the more recent visit by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in November. But the strategists of US imperialism are very unsure how to proceed.

The Americans saw the Ukrainian advances on the battlefield (won mainly as a result of the active involvement of US imperialism) merely as a bargaining chip, designed to give the Ukrainians greater leverage at the negotiating table.

In practice, however, the successful Kharkiv offensive and the Russian withdrawal from Kherson has complicated the state of play on the diplomatic chess board. On the one hand, Zelensky and his generals were puffed up with their unexpected gains and wished to go much further.

On the other hand, the military setbacks represented a humiliating blow for Putin, who has drawn the conclusion that he needs to step up his “special military operation”. Thus, neither side is in a mood to negotiate anything meaningful at present. But that will change.

Zelensky’s demagogy, constantly insisting that they will never give up an inch of land, is clearly designed to put pressure on NATO and US imperialism by showing that the Ukrainians will fight to the end, always on condition that the West continues to send huge amounts of money and arms.

But the polls show that public support for the war in Ukraine is rapidly evaporating, as The New York Times already pointed out on 19 May 2022:

“Americans have been galvanized by Ukraine’s suffering, but popular support for a war far from U.S. shores will not continue indefinitely. Inflation is a much bigger issue for American voters than Ukraine, and the disruptions to global food and energy markets are likely to intensify.

(…)

“But as the war continues, Mr. Biden should also make clear to President Volodymyr Zelensky and his people that there is a limit to how far the United States and NATO will go to confront Russia, and limits to the arms, money and political support they can muster.”

And as Business Insider reported on 27 September 2022:

“A new poll suggests that many Americans are growing weary as the US government continues its support of Ukraine in its war with Russia and want to see diplomatic efforts to end the war if aid is to continue.

“According to a poll conducted by the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and Data for Progress, 57% of likely voters strongly or somewhat support the US pursuing diplomatic negotiations as soon as possible to end the war in Ukraine, even if it requires Ukraine making compromises with Russia.”

Nuclear war?

Biden would like to prolong the present conflict in order to weaken and undermine Russia. But not at any price, and certainly not if that involves a direct military clash with Russia.

Putin’s hint that he might consider using nuclear weapons was almost certainly a bluff, but it caused alarm in the White House. Speaking at a fundraiser in New York, Biden said Russia’s president was “not joking” about the “potential use of tactical nuclear weapons or biological or chemical weapons because his military is, you might say, significantly underperforming”.

“We have not faced the prospect of Armageddon since [President John] Kennedy and the Cuban missile crisis,” Biden said, adding that “we have a direct threat of the use of nuclear weapons if in fact things continue down the path they are going.”

The Financial Times understands that secret negotiations are taking place between Washington and Moscow:

“President Joe Biden’s sobering remarks about the threat of the use of nuclear weapons show that the White House is clear-eyed about the risk of escalation. For understandable reasons, Washington wants to maintain strategic ambiguity in public while communicating its views to the Kremlin in private.

“However, attempts to use a combination of new sanctions, more diplomatic isolation and possibly conventional NATO strikes against Russian military targets in Ukraine to deter a desperate Putin from using weapons of mass destruction, should he feel cornered, are by no means guaranteed to succeed. To improve the chances of preventing a showdown, the quiet groundwork for crisis diplomacy should be laid now.”

Despite all the noise about Putin planning to use nuclear weapons, there are no credible reports to suggest that this is the case. He has no need for such weapons. On the Russian side, this is evidently a bluff (and one that has had some effect).

But the Russians have accused the Ukrainians of preparing to use a “dirty bomb”, that is, conventional explosives laced with radioactive material.

This may be true or just part of the propaganda war. But it is very clear that the Ukrainian side is getting increasingly desperate and looking for any excuse to stage a provocation that they hope will finally drag NATO into direct participation in the war. It is not at all excluded that the Russian claim may be true.

This underlines the dangers that are implicit if the war is allowed to continue. There are too many uncontrollable elements in play, which might give rise to the kind of downward spiral that could lead to a real war between NATO and Russia.

In the event of a general European conflagration, it would be impossible for the Americans to stand on the sidelines, warming their hands on the flames. There would have to be American troops on the ground. But that was not supposed to be part of the script!

Biden has said he was trying to find a way for Putin to back down. “I’m trying to figure out: what is Putin’s off-ramp?” Biden said. “Where does he find a way out?”

In other words, it is Joe Biden who is now looking for a way out. But that is easier said than done.

To negotiate or not negotiate?

In the first month of the war, Ukraine and Russia held talks in which Ukraine promised it would remain neutral in exchange for the return of its territories.

But Russia called for Ukraine to recognise its annexed territories and the ‘demilitarisation’ and ‘denazification’ of Ukraine – terms that Ukraine and its western allies refused to consider.

As noted, since then, Zelensky has said Ukraine is only prepared to enter negotiations with Russia (though not with Putin) if its troops leave all parts of the country, including Crimea and the eastern areas of the Donbas, de facto controlled by Russia since 2014, and if those Russians who have committed crimes in Ukraine face trial.

But these declarations have caused much irritation in Washington and beyond. The Washington Post revealed that US officials have warned the Ukrainian government in private that “Ukraine fatigue” among allies could worsen if Kyiv continues to refuse to negotiate with Putin.

While the US has so far given Ukraine $18.9bn (£16.6bn) worth of aid and says it will support Ukraine “for as long as it takes”, allies in parts of Europe, not to speak of Africa and Latin America, are concerned by the strain that the war is putting on energy and food prices as well as supply chains.

For the Ukrainians, acceptance of the US request to negotiate would mean a humiliating retreat after so many months of belligerent rhetoric about the need for a decisive military defeat against Russia in order to secure Ukraine’s security in the long term.

Is Putin in danger of overthrow?

The western propaganda is mere wish-fulfilment. It is based on a fundamental misconception. Putin has huge support, and this has risen to new levels in recent months. He is not in any immediate danger of overthrow.

There is no significant anti-war movement in Russia, and what little exists is led and directed by the bourgeois-liberal elements. That is precisely its main weakness. The workers take one look at the pro-western credentials of these elements, and turn away, cursing.

The only pressure on Putin comes, not from any anti-war movement, but on the contrary, from the Russian nationalists and others who want the war to be pursued with greater force and determination.

As for Russia, at the moment the war has the support of the majority, even if some have doubts. The imposition of sanctions and the constant stream of anti-Russian propaganda in the West, the fact that NATO and the Americans are supplying modern weapons to Ukraine, confirms the suspicion that Russia is being besieged by its enemies.

The weakness (more correctly, the absence) of the anti-war movement has already been commented on. However, if the war drags on for any length of time without significant proof of a Russian military success, that can change.

In early November, more than 100 conscripts from Russia’s Chuvash Republic organised a protest in Ulyanov Oblast because they had not received payments promised by the Russian president.

The protesters were quickly ‘pacified’ by riot police and Russian National Guard officers. But the rebellious mood of the troops was an ominous symptom for the authorities. The video of the disturbance included such comments as:

“We’re risking our own lives and going to certain death for the sake of your security and peace. Our government is refusing to pay us the 195,000 roubles that President Vladimir Putin promised us! So why should we go to war for this state, leaving our families without support?

“We refuse to take part in the ‘special military operation’ and will seek justice until we’re paid the money that was promised to us by the government led by the President of the Russian Federation!”

A small symptom, no doubt. But if the present conflict is prolonged, it could be multiplied on a far-bigger scale, posing a threat, not just to the war, but to the regime itself.

The most significant symptom is the protests of the mothers of soldiers killed in Ukraine. These are still small in size and mainly concentrated in the Caucasian Republics like Dagestan, where high levels of unemployment meant that large numbers of young men volunteered for the army.

If the war continues and the number of deaths increase, we may see protests of mothers in Moscow and Petersburg, which Putin cannot ignore and will be unable to repress. This would undoubtedly mark a change in the whole situation. But it has not materialised – yet.

What now?

The war in Ukraine has now become an important factor in world perspectives. However, there are so many variables in this equation that it is impossible to predict accurately the outcome of this war. Nor is it possible to determine with any degree of accuracy how long it may last.

War is a moving picture with many unforeseeable variants. Napoleon’s saying that war is the most complex of all equations retains its full force.

The variant that has been confidently advanced by the western propaganda machine ever since the commencement of hostilities appeared to be validated by the success of the Ukrainian offensive in September, and now by the Russian withdrawal from the western part of Kherson.

However, we must guard against impressionistic conclusions drawn from a limited number of events. The outcome of wars is rarely decided by a single battle – or even by several battles. The question is: did this victory, or that advance, materially alter the underlying balance of forces, which alone can determine the final result?

Thus far, the Ukrainians have shown a remarkable level of resilience. But how long the morale of both the civilian population and the soldiers at the front can be maintained is unclear.

More importantly, how long will America and the West be prepared to spend vast amounts of money on a war that appears to have no clear end in sight, and which is placing intolerable strains on the world economy, driving social contradictions to the limit and testing political stability to breaking point.

These fundamental questions have yet to be determined. Time will tell which link in the chain will break first. For the time being, the bloody conflict will grind on, bringing untold misery to millions of people.