With his latest film, the Death of Stalin, British director and comic writer Armando Iannucci continues with his recurring motif of the cynicism and self-interest of the professional political class. This time, however, the incompetent politicians being lambasted are not those of the Western establishment, but of the Stalinist bureaucracy.

British director and comic writer Armando Iannucci has carved out a name for himself over the last couple of decades as the sharpest and most perceptive political satirist of a generation.

His TV series The Thick of It and Veep accurately portray the incompetence and opportunism of the individuals at the heart of (respectively) the British and American political apparatuses. In his debut feature film In the Loop, meanwhile, Iannucci married the two, providing a brilliant critique of the so-called “special relationship” and the machinations of “dodgy dossiers”, etc. surrounding the 2003 Iraq War.

With his latest film, the Death of Stalin, Iannucci continues with his recurring motif of the cynicism and self-interest of the professional political class. This time, however, the politicians being skewered are not those of the Western establishment, but of the Stalinist bureaucracy. Nevertheless, despite the different context, the message is the same: those in power rarely deserve it, and are only motivated by one thing – their own egotistical careerist interests.

Carry on up the Kremlin

Based on a French graphic novel of the same name, The Death of Stalin – as the title suggests – follows the events that took place in 1953 in the wake of the Soviet dictator’s sudden passing away. Above all, the film demonstrates (with some artistic licence in relation to historical facts) the Machiavellian scheming and chaotic backstabbing that occurred in the aftermath of Stalin’s death, as the various members of the leadership jostled for power.

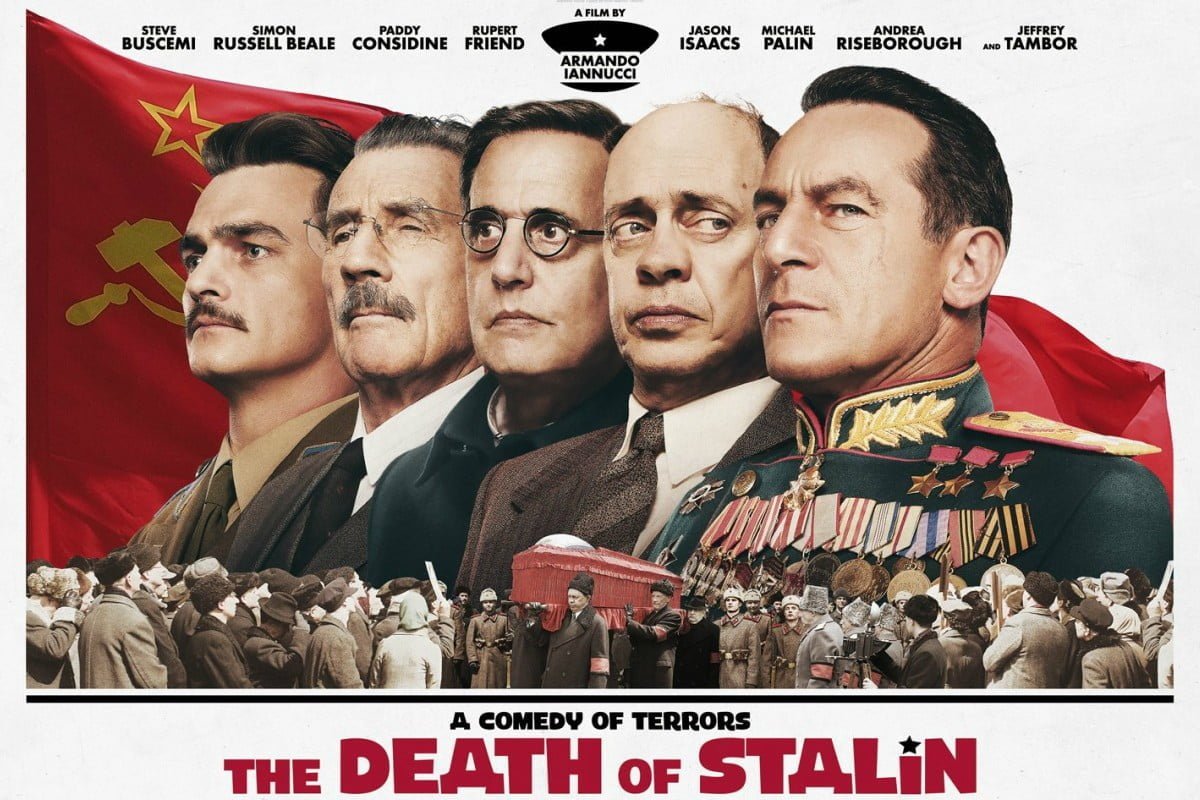

Along the way, an all-star cast hilariously impersonates the different Politburo ministers: from Michael Palin’s confused Molotov, who desperately struggles to keep up with the rapidly changing party line; to Steve Buscemi’s Khrushchev, who acts as puppet-master in the plot to push aside Simon Russell Beale’s brutal Beria, the ruthless chief of the secret police.

Meanwhile, Stalin’s progeny – the sheltered Svetlana and alcoholic Vasily – are used as pawns by rival potential successors, who hope to gain the children’s confidence in order to add legitimacy to their leadership bids. Jeffrey Tambor and Jason Isaacs complete the stellar line up as the bumbling temporary premier, Malenkov, and the arrogant army general, Zhukov, respectively.

The most entertaining and insightful sections of the film are the almost surreal absurdities surrounding the inept bureaucracy’s attempts to impose their authority and appear omnipotent despite their obvious amateurism. No wonder that one reviewer in the Guardian described the film as being “Carry on up the Kremlin”.

In one particularly memorable scene, for example, the Council of Ministers is left confused by their own rigid routines, with a reluctant Khrushchev forced to vote against his own interests in order to maintain an artificial unanimity, and a rambling Molotov tying himself and the rest of the Politburo in knots as he tries to square the various circles facing the clueless Council members.

In the process, Iannucci echoes Leon Trotsky’s biographical analysis of Stalin and the Soviet apparatus, where the Russian revolutionary describes the grey blandness and mediocrity of the regime – a reflection of the stultifying top-down control and narrow perspective of the bureaucratic caste.

A monstrous regime

Despite its generally humorous tone, the Death of Stalin does not shy away from darkly demonstrating the savage cruelty of the Stalinist regime. Indeed, the film’s opening sequence – of an anxious musical director locking a concert’s audience in the venue as he tries to record a concerto at the Soviet leader’s request – aptly demonstrates the almost farcical situations that genuinely arose as a result of the ubiquitous fear that existed about falling foul of Stalin and his terrorising machinery.

Elsewhere, meanwhile, we see the Politburo’s members callously laughing amongst themselves about the impossibility of remembering who they have already purged; whilst chilling screams dedicated to the dictator’s honor – the final words of Stalin’s many victims – are heard as Beria stridently walks through the corridors of the secret police’s HQ.

It would be easy for more liberal commentators to claim, in this respect, that Iannucci’s latest film is a dig at the ideas of socialism and communism; a satirical attack – made on the centenary of the 1917 October Revolution – against the supposedly “inevitable” authoritarian regimes arising out of Marxist-inspired revolutions.

But such an analysis would be profoundly mistaken. In the context of the director’s previous work, it is clear that the real target is not simply the Stalinist bureaucracy in particular, but the incompetent and purely self-motivated political establishments seen throughout history.

Indeed, the plotting and power struggles at the centre of the Death of Stalin are a repeating feature of Iannucci’s TV series also: from the manoeuvres of the Labour leadership contest in series two of the Thick of It; to the desperate and self-seeking presidential bids of Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ protagonist in Veep.

Smash the status quo

With such buffoonish and blundering world leaders as Donald Trump and Theresa May now sitting in the White House and Downing Street respectively, it is clear that Iannucci’s overarching critique of the political class still has much resonance in these modern times.

Nevertheless, it is ultimately a viewpoint that verges on an almost-dangerous nihilism: a “plague on both your houses” cynicism towards all politicians and all of politics, which – whilst understandable on the back of decades of superficial soundbites, establishment scandals, and deceit from Blairites and Tories alike – has the potential to feed the alienation and apathy felt by many ordinary workers and youth.

Indeed, in all of Iannucci’s political creations, the focus is always solely on the intrigues at the top; the masses are always either not to be seen, or – as in the Death of Stalin – are simply passive recipients of the establishment’s decisions. The conclusion drawn is that society is forever doomed to be ruled over by out-of-touch and unrepresentative leaders. The faces may change, but the system always preserves and renews itself.

Now, with the Corbyn movement on the rise, providing hope and optimism and drawing in a whole new generation of activists, it is necessary to paint a radically different picture: not one simply of an incompetent, undeserving, and immovable caste of bureaucrats and mandarins, but one showing the potential to change society from the bottom up by getting organised and fighting to smash the rotten status quo.