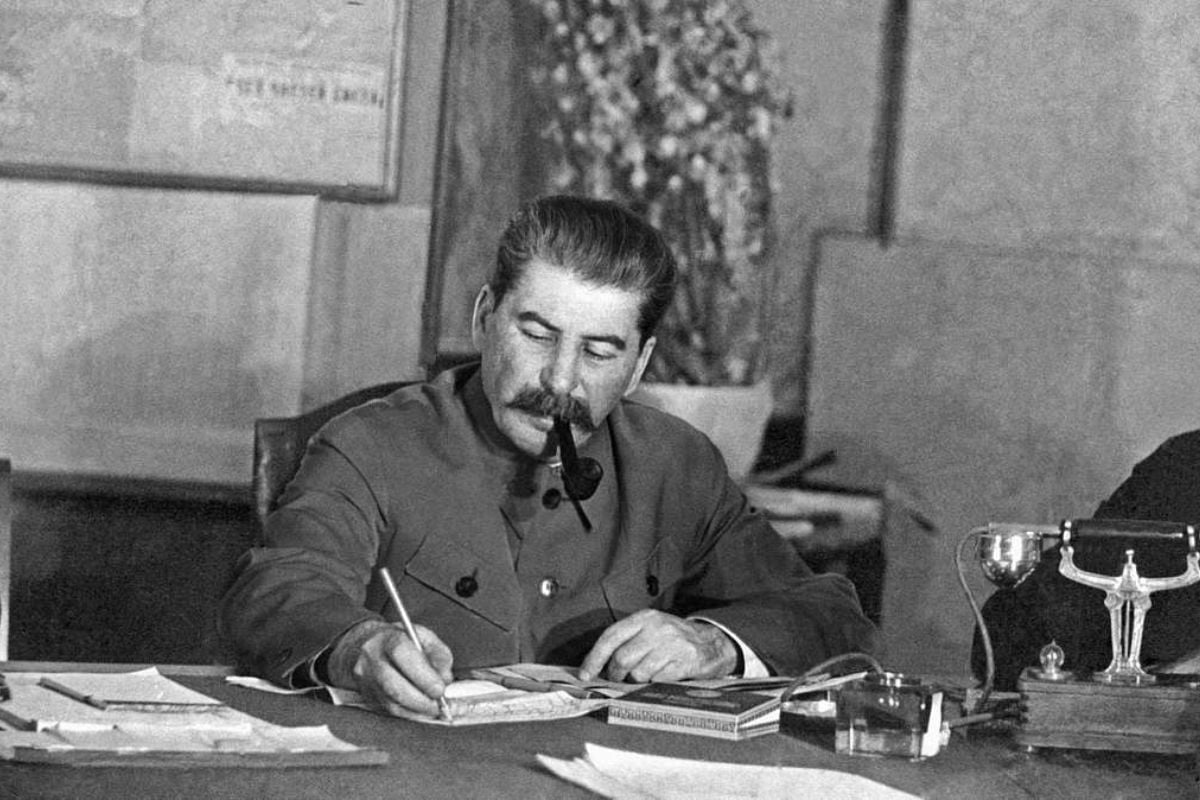

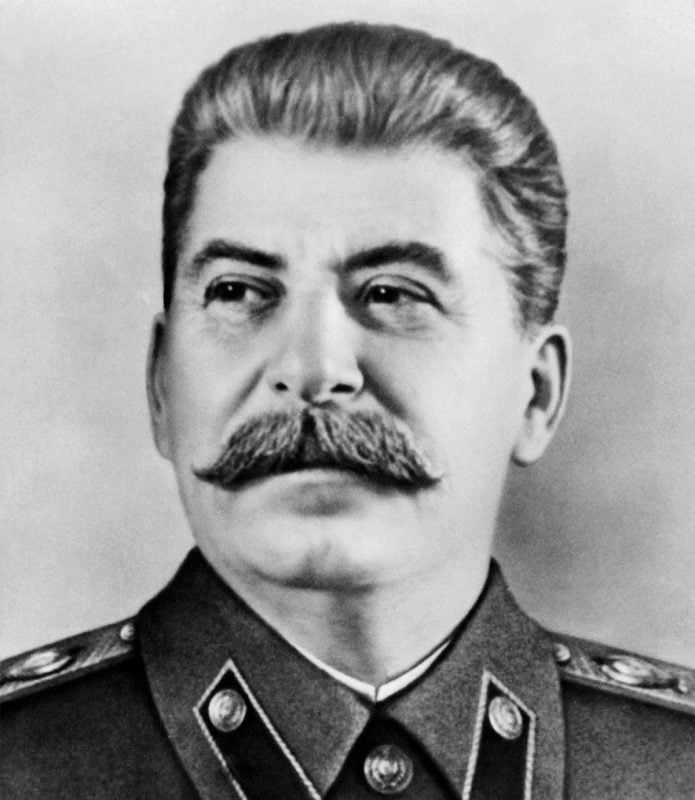

On 5 March 1953, Joseph Stalin, the gravedigger of the October Revolution, died. His regime had been characterised by monstrous repression, with a river of blood separating his dictatorial rule from the genuine traditions of Bolshevism established by Lenin.

It was also a reign marked by spectacular catastrophes, such as the famine of the 1930s and the needless loss of millions of Red Army soldiers in the first stages of the war.

Stalin died in fairly suspicious circumstances. The longer he held power, the greater his paranoia grew. By the 1950s, having instigated an antisemitic campaign against mainly Jewish doctors, Stalin was preparing for another mass purge. Fearing the ramifications for themselves, and for wider Soviet society, it is believed top figures of the bureaucracy may have hastened his end.

Yet how had the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 come to this?

On this day in 1953, Joseph Stalin, the man who spearheaded the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union, died following a stroke. In this video, Alan Woods explains how Stalin came to play this ignominious role.

🔗 https://t.co/pUOa9gr9S0 pic.twitter.com/UlygnaVOWu

— Socialist Appeal (@socialist_app) March 5, 2023

Origins of Stalinism

There is a perfidious lie that the regime of Stalin was a natural continuation of that of Lenin. This is false to the very core.

The regime established by Lenin and Trotsky was amongst the most democratic in history, basing itself as it did on the soviets. These were organs of the working class, peasants, and soldiers, which reflected the mood of the masses far more accurately than any parliament.

The soviets provided direct representation, and established the right of recall. This meant that deputies who were out of tune with the masses could be replaced. This was a far cry from the totalitarian dictatorship of Stalin.

So how was it that this brutish figure came to usurp the October Revolution and roll back many of its gains?

To understand this, we must look at the situation in which the fledgling workers’ state found itself.

From the outset, the young workers’ state faced enormous challenges. These undermined the basis for a healthy regime of workers’ democracy.

The October Revolution provoked horror and dread amongst the ruling classes of the world. Immediately, the young Soviet republic was invaded by 21 imperialist armies, who supported the efforts of the counter-revolution in Russia. This plunged the country into a bitter civil war.

The civil war – along with WW1 before it – completely shattered industry. In 1920, the production of iron ore and cast iron fell to 1.6% and 2.4% of their 1913 levels. The output of industrial commodities stood at just 12.3% of their pre-war level. Similarly, agriculture was ruined, with the 1921 harvest producing just 37.6 million tons of various crops – just 43% of the pre-war average.

Isolation and backwardness

Perhaps the most crucial consequence of the civil war was the direct impact it had on the working class. The war itself claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of workers. Many of those who survived migrated to the countryside, so desperate was the breakdown of society in the towns and cities.

By the end of the war, the working class had been decimated, and the material conditions required to maintain genuine workers’ democracy had been further eroded.

The industrial collapse undermined one of the major conquests of the October Revolution – the eight hour day. In order to produce even the most basic articles of consumption, workers had to work 10, 12, or even 14 hour days, and had to forgo their weekends.

In short, the time necessary for workers to engage in the soviets simply didn’t exist. As a result, workers’ control in society, industry, and politics was impossible.

Moreover, the historic backwardness of Russia meant most workers were illiterate, and consequently were unable to take part in the management of industry.

In all regards, a healthy regime of workers’ democracy was impossible. This was the material basis for the cancerous growth of a bureaucracy in the Soviet Union.

Even more decisive was the isolation of the revolution. Lenin and Trotsky correctly saw the October Revolution as the beginning of the world proletarian revolution. Yet tragically, the revolutions that did spring up in the years after 1917 – in Germany, Hungary, Italy, and China – were all defeated.

The responsibility for many of these defeats rests with the reformist leaders, who consciously betrayed them. Yet in a number of them, Stalin also played a decisive role, as we shall see.

As a result of the delay of the world revolution, there existed a deep contradiction within the USSR. On the one hand, the working class was incapable of running society. But on the other hand, the bourgeoisie had been defeated and capitalism had been overthrown.

It was from this vacuum that a permanent layer of functionaries emerged: the former managers and administrators of Tsarist Russia. These opportunistic, well-to-do ladies and gentlemen formed the basis of the bureaucracy. And as their weight in society increased, with the revolution isolated and the working class exhausted, Stalin would increasingly come to embody the bureaucracy’s interests.

Revolutions betrayed

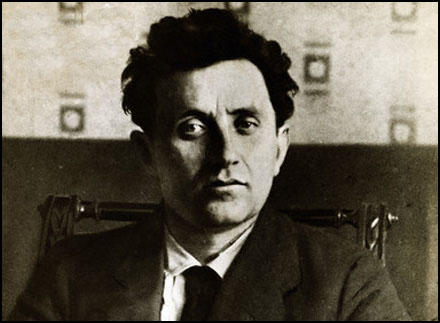

The bureaucracy crystallised around Stalin in part because he was almost their living embodiment. He held a narrow, bureaucratic outlook. He was a competent organiser. And he was ruthlessly ambitious.

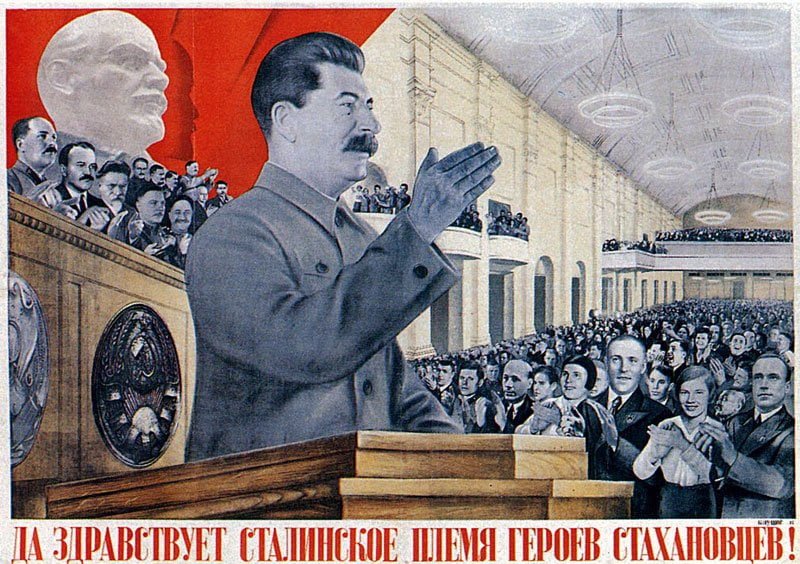

This bureaucratic caste was keen to maintain and increase its own power and privileges. This meant ending the upheaval of revolution, establishing order, and maintaining the status quo.

It was for this reason that Stalin would come to champion the ‘theory’ of ‘socialism in one country’, which provided a cover for abandoning socialist internationalism and the goal of world revolution.

In the eyes of the short-sighted, parochial bureaucracy, world revolution was unrealistic and undesirable. Instead, they wanted to strike deals with capitalist regimes. These careerists had what they wanted from the revolution, and wanted it to go no further.

‘Socialism in one country’, in reality, meant socialism in no country. At first, it reflected a general cynicism from Stalin that the workers couldn’t take power and transform society outside of Russia.

This was seen in his approach to the extremely favourable situation for revolution in Germany in 1923. “In my opinion, the Germans should be restrained and not spurred on,” Stalin wrote. Given the inexperience of the German communists, this advice was fatal, and the revolution was defeated.

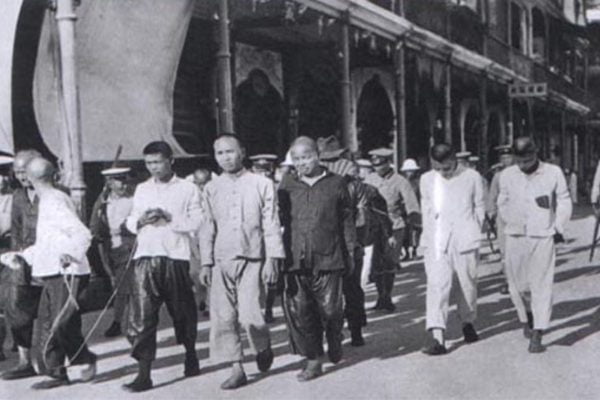

Similarly in the Chinese Revolution of 1925-27. Stalin’s complete lack of faith in the Chinese working class led him to pursue a completely opportunist alliance with the bourgeois Guomindang party. This led to a disastrous policy of the young Chinese Communist Party subordinating itself entirely to a bourgeois nationalist party. The end result was the smashing of the Communist Party by the Guomindang and the defeat of the revolution.

Bureaucracy strengthened

These defeats of the working class internationally further demoralised and isolated workers in the Soviet Union. This, in turn, emboldened and strengthened the bureaucracy. But it was not the only layer of Soviet society that was encouraged by these reversals of the world revolution.

In 1921, the Bolsheviks had been forced by the isolation of the revolution to adopt the New Economic Policy (NEP). This meant reintroducing market relations in the countryside, in order to incentivise peasant proprietors to produce more food.

The problem was that the policy disproportionately benefited the kulaks – the rich peasants. They had larger landholdings, which allowed them to produce agricultural goods more efficiently. This meant that they could profit more from selling their surpluses.

The trade between peasants and the cities, in turn, was facilitated by so-called NEPmen – a class of petty merchants and speculators who spied an opportunity to make a quick buck.

These layers were naturally hostile to Soviet power, and sought the restoration of capitalism.

Trotsky and the Left Opposition had consistently warned against this threat. Stalin, meanwhile, leaning on Bukharin’s Right Opposition, had encouraged the kulaks to ‘get rich’, in order to develop the economy.

The ramifications of this policy came to the surface by around 1927. The kulaks began to withhold grain, and the threat of starvation in the cities loomed once more. And Stalin, the crude empiricist that he was, suddenly made an about face in 1929 – breaking with Bukharin and calling instead for the liquidation of the kulaks as a class.

Stalin began to adopt huge swathes of the Left Opposition’s programme. But did so in a crude, distorted, caricatured manner. This created huge problems.

Industrialisation was massively accelerated, to the point of adventurism. Infamously, Stalin even called for the first five-year plan to be completed in four years. Crucially, these measures were combined with the most brutal suppression of the Left Opposition itself.

Trotsky and the Left Opposition were the proletarian vanguard. But this proletariat had been drained by events. In a physical sense, they’d been devastated by war. In 1917, there were 3,000,000 industrial workers in Russia. By 1920, this figure had fallen to 1,240,000. Politically, meanwhile, workers had witnessed defeat after defeat on the international plane.

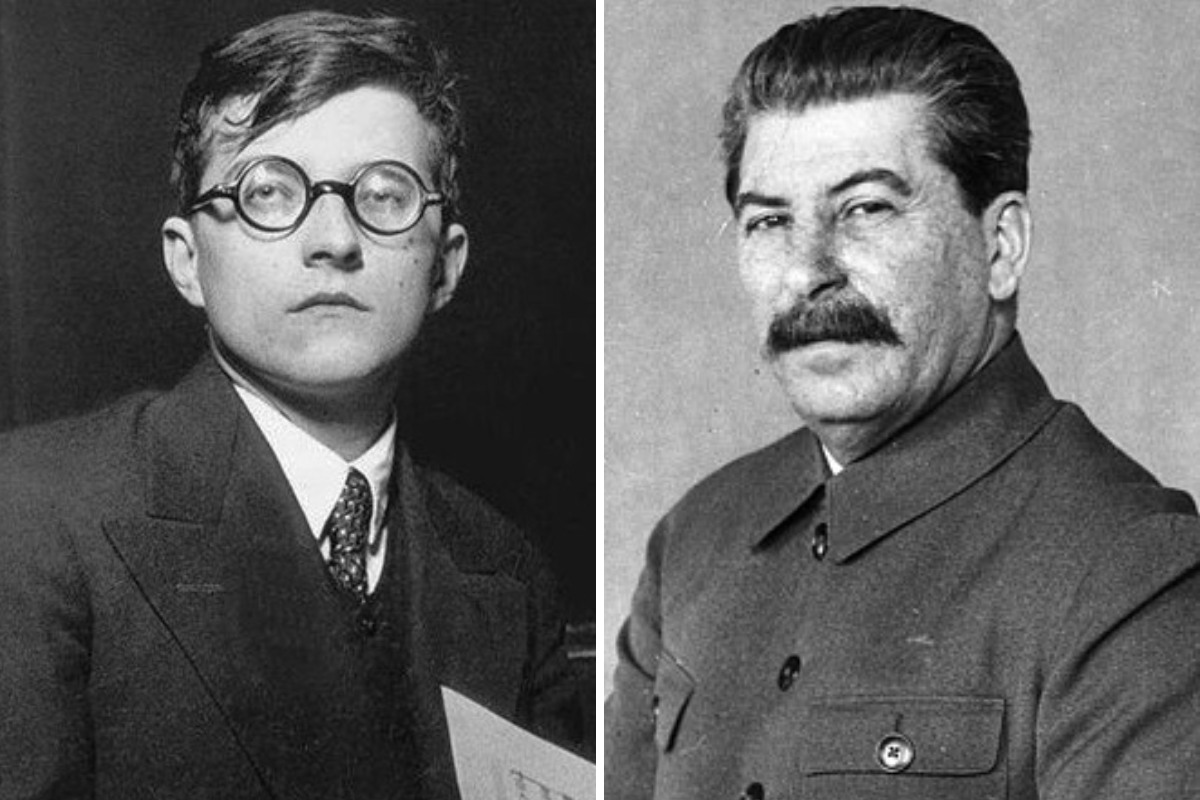

The clash between Stalin and Trotsky was ultimately a struggle of living social forces. The exhaustion of the working class thus enabled Stalin to exile Trotsky to Alma Ata in the Kazakh Soviet Republic, before exiling him from the USSR altogether in 1929.

Alongside this, there was a wave of expulsions of anyone hostile to Stalin’s policies. His grip on power – reflecting the strengthening of the bureaucracy – became absolute. As Trotsky put it:

“In its struggle against the Left Opposition, the bureaucracy undoubtedly was dragging behind it a heavy tail in the shape of Nepmen and kulaks. But on the morrow this tail would strike a blow at the head, that is, at the ruling bureaucracy…As early as 1927, the kulaks struck a blow at the bureaucracy, by refusing to supply it with bread.”

This crisis accelerated Stalin’s Bonapartist grip. The bureaucracy was petrified that it could be overthrown from the left or the right. In Stalin, this bureaucratic caste saw a strongman who could defend their privileged position from these acute threats.

Stalin’s purges

Many a sneering liberal has tried to claim that socialism inevitably leads to the kind of bloodletting and horrors that Stalin oversaw. Yet this entirely misunderstands who this violence was directed at, and for what reason.

The chief target of Stalin’s purges were the Old Bolsheviks themselves – anyone who had a connection with the October Revolution.

So it was that, of the Bolshevik Central Committee that led the working class to power in 1917, only Stalin and Kollontai were still alive by 1940. Most were murdered by the GPU (the Soviet Union’s secret services) at Stalin’s behest. Even the total capitulation of figures like Kamenev, Zinoviev, and Radek did not save them.

True enough, many of the victims of the purges were bureaucrats themselves. Does this suggest that, in a ham-fisted way, Stalin was striving to defend workers against the bureaucracy?

In reality, layers of the bureaucracy were targeted for the same reason that a doctor might recommend an amputation: to cut off the part to save the whole.

Stalin leaned on the workers to strike blows against the most rotten elements of the bureaucracy: those whose voracious greed threatened to stir the workers and topple the entire edifice; those whose ambition represented a threat to Stalin’s position and to the bureaucratic machine as a whole.

So it was that over a million perished – not to establish socialism, but to preserve the rule of a parasitic caste of functionaries.

Thermidorian reaction

The purges were a culmination of what Trotsky characterised as the ‘Thermidorian reaction’ in the USSR.

Basing his analysis on the analogy of the French Revolution, Trotsky concluded that what had occurred in the Soviet Union was a political counter-revolution from within.

Having overturned the old order in October 1917, the working class had subsequently lost political power. Nevertheless, the social conquest of the revolution – the nationalised planned economy – remained.

This was comparable to the process of the French Revolution. Robespierre’s Jacobin faction, the most revolutionary section of the movement, was deposed by more conservative elements from within the revolution.

Eventually Napoleon Bonaparte seized power. In 1804, he proclaimed himself Emperor, undoing the political gains of the republic. Yet Napoleon did not restore feudalism in France. Instead, he based his regime on the new capitalist relations that had been established by the revolution.

Similarly in the USSR, Stalin based himself on the nationalised planned economy. Representing the bureaucracy, however, he had politically usurped the working class. Socialist property relations remained, but many of the gains of the revolution were rolled back.

The most obvious expression of this was the complete annihilation of workers’ democracy inside the Soviet Union, in favour of the rule of the bureaucracy, alongside the counter-revolutionary role played by Stalinism internationally.

Zigzags and catastrophes

Stalin never really grasped the Marxist method. Indeed, the Old Bolshevik Yeveny Frolov claimed that “Stalin struggled to understand philosophical questions, without success”. Instead of applying dialectical materialism to problems, he adopted a crude empiricism approach – with disastrous consequences.

This first manifested itself with Stalin’s adherence to the New Economic Policy. He viewed its relative success – in comparison to the previous period of ‘war communism’ – as proof that there was no need for a change of course.

Neglecting to analyse the NEP in an all-sided manner, such as its impact on class formations, he failed to see the latent political danger that it carried: strengthening market relations and emboldening the kulaks and petty traders.

Empirically, Stalin later drew the conclusion that private capital accumulation in agriculture was not the way forward. Consequently, he did a volte-face, launching a campaign to forcibly collectivise agriculture and liquidate the kulaks as a class.

No consideration was given to whether collectivisation was possible; whether the country’s industry could furnish peasants with the machinery and resources required to make collective farming successful.

As a result, the policy led to a total and utter catastrophe in agriculture, provoking a famine that killed millions, and leaving a lasting scar in the countryside.

‘De-Stalinisation’

Stalinism can be defined as the bureaucratic (mis)management of the planned economy. From this flows the political dictatorship required to protect the power and privileges of the bureaucratic caste. But did this system die with its boss?

In his ‘Secret Speech’ in 1956, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev attempted to pin the blame for all the horrors and catastrophes of the preceding decades onto Stalin and his ‘cult of personality’.

Stalin had placed emphasis on developing heavy industry at a blistering pace, at the expense of consumer goods and housing. This meant that living standards were still much lower in the USSR than in the West.

By the 1950s, this was preparing a social explosion, particularly as the bureaucracy furnished itself with limousines and dachas. According to historian Roy Medvedev, wage differentials between top bureaucrats and workers stretched to as much as 100-to-1.

Under Khrushchev, therefore, economic concessions were granted from above in order to prevent political revolution from below.

Between 1955-58, the average factory wage was raised from 715 roubles a month to 778. Meanwhile, official prices remained fixed, and some were even cut. Shorter hours were introduced for young workers, without a loss of pay, alongside longer holidays.

Given the decades of accumulated discontent, particularly in the satellite states of Eastern Europe, it did not take long for these concessions to encourage a movement from below.

As French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville perceptively noted: “The most dangerous moment for a bad government is generally that in which it sets about reform.” And so it was for the Soviet bureaucracy.

In October 1956, revolution broke out in Hungary. Workers and students were resentful of totalitarian rule, Soviet domination, and the deteriorating living standards that flowed from this. Indeed, disposable income for Hungarian workers in 1956 was two-thirds of what it had been in 1938 – a consequence of the Soviet Union draining the country through post-war reparations.

Contrary to the claims of the Stalinists, however, this was no counter-revolution. The manifesto under which the revolution was fought was issued by Péter Veres, the president of the Writers’ Union. The second demand of this read:

“The social and economic system of Hungary should be socialism built up by democratic means in accordance with our national characteristics. The 1945 agricultural reform and the public ownership of factories, great industrial enterprises, mines and banks, have to be maintained.”

Even more instructively, the revolution saw the formation of democratic workers’ councils – i.e. soviets. Yet what was the response of Khrushchev and co? It was to send in the tanks and brutally repress the Hungarian Revolution.

As Ted Grant put it at the time: “If the Kadar government really represented the masses and not the counter-revolution in Stalinist form, it would have based itself on the soviets or workers’ committees, as Lenin did in 1917.”

Stalin’s legacy

Stalin’s death, therefore, heralded no qualitative change. Stalinism remained in place, with tragic consequences for the working class, in Russia and internationally.

The bureaucratic monolith, which Stalin had stood at the head of, eventually came crashing down in 1991 – just as Trotsky had predicted in his masterpiece Revolution Betrayed.

This was Stalin’s real lasting legacy: to pave the way for capitalist restoration in the land of the October Revolution.

In marking the anniversary of his death, our role – as the philosopher Spinoza once stated – is neither to weep nor to laugh, but to understand.

Today, disgusted by capitalism, a new generation is turning towards communism. Our task is to organise and educate these class fighters in the genuine ideas of Marxism, and to prepare for the revolutionary upheavals that impend.