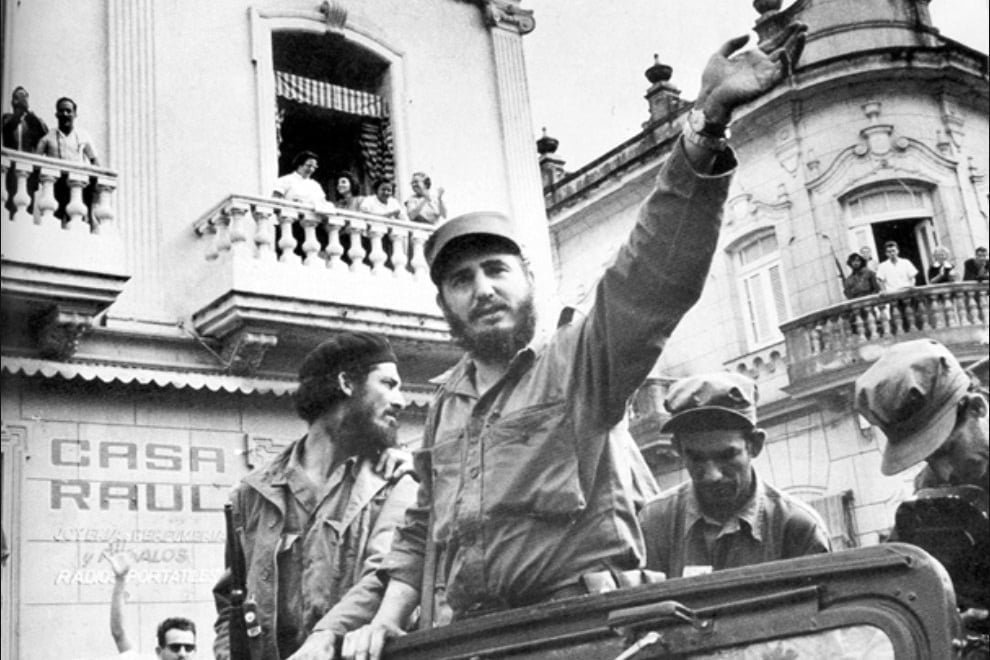

Sixty years ago, on New Year’s Day 1959, a general strike paralysed Cuba and forced dictator Fulgencio Batista to flee the country. Within a few days the 26th of July Movement guerrillas – led by Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara – had entered Havana and were received as heroes. The Cuban Revolution had succeeded.

Colonialism and imperialism

In 1898, Spain lost Cuba, one of the few remnants of her former colonial power. But that did not mean independence for Cuba. The island was just transferred from one colonial master to another: the United States of America.

For three years after 1898, Cuba was militarily occupied and ruled by the US. The Cuban Republic was only declared in 1902, after Washington passed the Platt amendment declaring the right of the US to militarily intervene in the island at any time. Cuban politics for the next 60 years were to be determined by the US, who did actually send troops to the island on several occasions: 1906, 1912, 1917, 1920 and 1933.

The Cuban economy was also largely dominated by the US. The island’s main source of income was sugar cane which was sold at preferential prices to its powerful northern neighbour. Most of the country’s sugar mills were in the hands of American companies and so were most of the other key sectors of the economy – oil, electricity, telephone etc.

This crushing domination by the US relied on a system of land property which remained basically the same as under Spanish domination: a few landowners had most of the land, while the majority of peasants were landless labourers.

The only other group to benefit from this situation was the small and very weak Cuban bourgeoisie, confined to manufacturing the very few things not made by US subsidiaries.

Meanwhile, the living conditions of the Cuban masses were appalling. In good years 25% of the workforce was still unemployed. This percentage went up to 50% in bad years. Illiteracy was very high and the average per capita income was only US$312.

For years the Cuban workers played a key role in the struggle against imperialism and to advance their own interests. A high point was the huge wave of strikes and demonstrations during the 1930s, including armed uprisings and the establishment of revolutionary councils in the sugar mills. This led to the overthrow of General Machado’s US puppet government by an army coup led by Fulgencio Batista.

Unfortunately, the Cuban Communist Party, instead of relying on the revolutionary might of the Cuban workers, adopted the Stalinist theory of the “two-stages”. According to this, they were supposed to look for an alliance with the so-called “progressive national bourgeoisie” in order to complete the “anti-imperialist and democratic revolution”. Only after that would the struggle for socialism be on the agenda.

Unfortunately, the Cuban Communist Party, instead of relying on the revolutionary might of the Cuban workers, adopted the Stalinist theory of the “two-stages”. According to this, they were supposed to look for an alliance with the so-called “progressive national bourgeoisie” in order to complete the “anti-imperialist and democratic revolution”. Only after that would the struggle for socialism be on the agenda.

This theory was utterly divorced from Cuban conditions and indeed from the real class relationships in any of the colonial countries. The Cuban landowners and the tiny bourgeoisie were completely linked to and dominated by the US. They had no intention whatsoever of carrying through the tasks of the bourgeois revolution (distribution of the land; fight for national independence) because that would have meant dealing a mortal blow to themselves.

The Cuban Communist Party in its search for a non-existent “progressive national bourgeoisie” discovered Batista to be the representative of this class and decided to support him. In exchange, the CP was legalised during the Batista dictatorship and even got two cabinet ministers in 1942.

Batista was replaced by the corrupt civilian government of Grau San Martín which in turn was overthrown by Batista in a second military coup in 1952. A succession of corrupt governments and military coups – with the real power in the island remaining firmly in the hand of the US and their local crooks – created widespread discontent amongst the population, including the petit-bourgeois layers.

26th of July Movement

In 1953, a group of students and intellectuals decided to do something to put an end to this state of affairs. With a handful of followers, this group launched an assault on the Moncada barracks on 26th July. Amongst them were Fidel Castro and his brother Raul.

In 1953, a group of students and intellectuals decided to do something to put an end to this state of affairs. With a handful of followers, this group launched an assault on the Moncada barracks on 26th July. Amongst them were Fidel Castro and his brother Raul.

They were defeated and jailed, but as soon as they were released they went to Mexico where they set themselves the task of organising a guerrilla group: the July 26th Movement (M-26J). They landed back in Cuba in 1956.

The programme of this movement was that of the revolutionary petit-bourgeoisie: distribution of land plots of more than 1,100 acres with compensation for the owners; a profit-sharing scheme for the workers aimed at expanding the domestic market; and the end of the quota system, under which the US controlled sugar cane production.

The 1956 Programme Manifesto of the M-26J defined itself as “guided by the ideals of democracy, nationalism and social justice … of Jeffersonian democracy”. The same document also stated their aim to reach a “state of solidarity and harmony between capital and workers in order to raise the country’s productivity”.

They launched a heroic three year long guerrilla struggle, which won the overwhelming support of the Cuban people – with the obvious exception of the tiny handful of people directly linked to the landlords and US imperialism.

The main base of the movement during the fighting itself were the landless peasants and small producers in the countryside, for whom the only way of solving their problems was the expropriation of the landlords. Batista’s army, itself made up mainly of peasants, rapidly began to disintegrate during the fighting.

General strike

On 31st December 1958, Batista met with a small number to celebrate New Year’s Eve at the Columbia military camp. The dictator appointed general Cantillo as supreme chief of the armed forces and then fled to the Dominican Republic.

On 31st December 1958, Batista met with a small number to celebrate New Year’s Eve at the Columbia military camp. The dictator appointed general Cantillo as supreme chief of the armed forces and then fled to the Dominican Republic.

The manoeuvre by the henchmen of the dictatorship and imperialism was clear: to allow Batista to leave the country safely and install a military junta led by Cantillo; to appear to introduce change, so that nothing would really change.

Above all, US imperialism wanted to defend its interests on the island and that required a change of personnel. The M-26J replied with a call for a general strike. The message by Fidel Castro, broadcast by Radio Rebelde (Rebel Radio), in the early hours of January 1, 1959, was clear:

“Revolution yes, military coup no! To steal the victory from the people will only make the war longer! (…)

“The people and particularly the workers of the Republic must remain alert and follow Radio Rebelde, and urgently prepare in all workplaces for the general strike, which will begin as soon as the order is given, if necessary, to counter any attempt at a counter-revolutionary coup”.

The call for a revolutionary general strike was broadcast a few minutes later.

In Havana, the masses went out on the streets to celebrate the flight of the hated dictator and – together with the revolutionaries who had mutinied in the Castillo del Principe jail – took over key points in the city, official buildings, police stations, etc.

The forces of guerrilla commanders Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos were still some distance from the capital, in Las Villas. But the apparatus of the dictatorship was collapsing like a house of cards with its henchmen fleeing as fast as they could.

At the end of the day, Fidel Castro addressed the crowds in Santiago de Cuba, after the surrender of the troops stationed in the city. A new government was sworn in, presided over by Manuel Urrutia.

On 2nd January, Che and Cienfuegos made a triumphal entry in Havana and the Cantillo military junta fell. The general strike lasted from 1st January until the 4th, guaranteeing revolutionary victory and the final collapse of the rotten apparatus of the Batista dictatorship.

Permanent revolution

The revolution that won 60 years ago in Cuba had an advanced democratic programme – for national liberation and agrarian reform, with a strong social content – but one which did not raise the issue of the abolition of capitalism in order to carry out these tasks.

Anyone who reads the speeches of the leaders of the revolution in those initial months of euphoria, the decrees they passed, the measures that were taken, can easily see that socialism was not on the agenda (although it is also true that there were some in the revolutionary leadership who already considered themselves socialists or communists).

Soon after seizing power Castro went to the US on a goodwill tour declaring in New York: “I have clearly and definitely stated that we are not Communists…The gates are open for private investment that contributes to the development of Cuba”.

The problem was that even a limited programme of progressive reforms clashed head on with the interests of the big landlords and the US multinationals. In other words, to carry through the programme of the democratic bourgeois revolution in a backward country in the epoch of imperialism meant to challenge capitalism and imperialism itself. This had already been proved by the practical experience of the Russian Revolution in 1917.

The Bolsheviks had argued that the national democratic revolution could only be led in a backward country like Russia by the working class, which represented no more than 10% of the population at that time.

The workers, having taken power at the head of the other oppressed classes, especially the peasantry, would then proceed to carry through the tasks of the socialist revolution as the only way to ensure the survival of the revolution.

But, as the national democratic revolution also challenged the interests of imperialism, in order to survive, the revolution had to spread internationally, seeking the help of the mighty working class in the advanced capitalist countries.

Leon Trotsky was the first one to give a full theoretical explanation of this theory. This is known as the theory of permanent revolution. The revolution in a backward country, therefore, has to be “permanent” in two regards: because it starts with the national democratic tasks and continues with the socialist ones; and because it starts in one country, but has to spread internationally in order to succeed.

Embargo

The events which followed Castro’s seizure of power in Cuba are a remarkable confirmation of this theory, which is even more striking because of the fact that Castro was forced to act in the opposite way to what he intended.

The events which followed Castro’s seizure of power in Cuba are a remarkable confirmation of this theory, which is even more striking because of the fact that Castro was forced to act in the opposite way to what he intended.

As soon as the new government started to seize the land owned by the big landlords (some of them US companies) they tried to organise resistance against these measures and were backed by the US. The masses, aroused by the revolutionary takeover, were also putting enormous pressure on the government with a wave of land seizures and factory occupations and strikes.

The conflict came to a head in 1960 when the three oil companies on the island (all of them US-owned) refused to refine a delivery of Russian oil to Cuba. The Cuban government then “intervened” placing them under government supervision. The US retaliated by cutting the quota for Cuban sugar, but Russia offered to buy it.

Then the Cuban government decided to nationalise the electricity company, the telephone company, the oil refinery and the sugar mills. Afterwards all Cuban subsidiaries of US companies were also nationalised and finally the biggest Cuban companies were taken into public ownership.

The US government retaliated by putting in place a trade embargo and preparing a military intervention to overthrow the regime. In 1961, all diplomatic relations between the two countries were broken.

As we have seen, Castro and his comrades had no intention whatsoever of eliminating capitalism on the island. They were pushed to do so by a combination of the mistakes and blunders of the US, and the pressure of the Cuban masses and their willingness to carry out their own program.

But the key factor was that no fundamental change could ever be implemented in Cuba under capitalism. In the epoch of imperialism, there is no room for a small colonial country to achieve real independence and advance unless it breaks fundamentally with capitalism. And this, Castro and his comrades of the M-26J found out by their own experience.

Bureaucracy

Undoubtedly, the support for the new regime was overwhelming. Two hundred thousand workers and soldiers were organised in a popular militia, with Committees for the Defence of the Revolution organised in every neighbourhood and every village. Thus when the CIA sponsored an invasion of the island in April 1961, the Cuban emigre invasion force was rapidly crushed by armed workers and peasants who – for the first time in their lives – had something to defend, something to fight and even die for.

The revolution enjoyed mass support since its advantages were there for everyone to see: an enormous advance in living standards; the eradication of illiteracy; one of the best health systems in the world, etc.

But the way the new regime had come to power was to shape the organisation of the new state. The working class is the only class that, because of its working conditions and the role it plays in production, is able to adopt a collectivist viewpoint.

During the process of the Russian Revolution hundreds of thousands of workers, peasants and soldiers went through the school of the soviets, revolutionary committees where all decisions were taken democratically, and gained confidence in their own ability to run their own lives.

But the Cuban revolution was led by a handful of intellectuals, and in the fighting itself no more than a few hundred participated. And this situation was to remain afterwards. There were workers and peasants’ militias and revolutionary committees, but their role was not to rule but only to approve decisions taken elsewhere. Hundreds of thousands gathered to listen to the speeches of the leaders, but they were not the ones taking the decisions.

The 1960s saw an open debate between the Cuban revolutionaries and the Stalinists over the direction of the movement on issues like spreading the revolution, economic policy, Marxist theory, and arts and culture. That came to an end in 1971, after the defeat of the attempts to spread the revolution, when the revolution became bureaucratised.

When the new regime broke with capitalism, the model it had was not that of Russian soviet democracy of 1917 but that of Russia 1961, where all vestiges of workers’ control had been eradicated long ago.

Which way forward?

In the 1990s, the collapse of Stalinism in the USSR left Cuba isolated. Unlike in Russia, however, here the leadership opposed any attempts to restore capitalism and the Cuban revolution resisted through the dire economic conditions of the “special period”.

In the 1990s, the collapse of Stalinism in the USSR left Cuba isolated. Unlike in Russia, however, here the leadership opposed any attempts to restore capitalism and the Cuban revolution resisted through the dire economic conditions of the “special period”.

A debate has opened in Cuba in recent years, with growing concessions to private capitalism being made. A section of the leadership sees China and Vietnam as a model to follow.

We must be very clear: had it not been for the revolution and the abolition of the private profit motive, Cuba would be today a poor and backward country in which the majority of the population would be living in poverty, facing unemployment, illiteracy and dying of curable diseases.

Any attempt to reintroduce capitalism will have disastrous consequences for the living conditions of the masses and would be a betrayal of the revolution.

Socialists all over the world have the duty to defend the Cuban Revolution against the attempts of US imperialism to destroy it. But also against the attempts of big business to restore the rule of capital bit by bit.

At the same time, we have to explain that genuine socialism cannot be established unless there is real workers’ democracy. And – above all – we must emphasise that socialism cannot be built on a single island.

The best contribution we can make to defend the gains of the Cuban Revolution is to fight for socialism in our own countries and internationally.