In bourgeois countries in the past, where the bourgeoisie has a role to play and looks forward confidently to the future – i.e. when it is genuinely progressive in developing the productive forces – it has decades and generations to perfect the state as an instrument of its own class rule. The army, police, civil service, middle layers and especially all key positions at the top; heads of civil service, heads of departments, police chiefs, the officer corps and especially the colonels and generals are carefully selected to serve the needs and interests of the ruling class. With a developing economy and a mission and a role they eagerly serve the ‘national interest’ i.e. the interest of the possessing class – the ruling class.

In Syria, as in all the ex-colonial countries, the imperialists, in this case the French, partly under the pressure of their rivals, especially American imperialism, were compelled to relinquish their direct military domination. The state which emerged is not fixed and static. The weakness and incapacity of the bourgeoisie gave a certain independence to the military caste. Hence the perpetual coups and counter-coups of the military. But in the last analysis they reflect the class interests of the ruling class. They cannot play an independent role.

The struggle between the cliques in the army reflects the instability and contradictions in the given society. The personal aims of the generals reflect the differing interests of social classes or fractions of classes of society, the petit-bourgeois in its various fractions, the bourgeoisie, or even under certain conditions the proletariat in so far as thay are successful in gaining power. The officer caste must reflect the interest of some class or grouping in society. They do not represent themselves though of course they can plunder the society and elevate their own ruling caste. Nevertheless they must have a class basis in a given society.

Bonapartist regimes do not rest on air but balance between the classes. In the final analysis they represent whichever is the dominant class in society. The economy of that class determines its class character. Some of these countries, as in Latin America, a semi-colonial continent which was under the domination of British then especially American imperialism for the last century, nevertheless, have been nominally independent for more than a century. In consequence, despite a period of turbulence the ruling class of landowners and capitalists has had sufficient period to perfect their state. Sometimes the armed forces of different fractions or factions of armed forces, can reflect different fractions of the ruling class and even the pressures of imperialism, primarily American imperialism.

But, up to now, they have always reflected the interest of the ruling class in the defence of private ownership.

In Burma, where the regime, newly emerged from British domination and where the ruling class was incapable of successfully ‘holding the country together’, it faced a series of rebellions and wars. The army was formed from the the Anti-Fascist Peoples Freedom League, which described itself as ‘socialist’.

With China as a model next door, the army leaders tired of the incapacity of the landowners and capitalists to solve the problems of Burma. Basing themselves on the support of the workers and peasants, they organised a coup, expropriated the landowners and capitalists and established Burma as a ‘Burmese Buddhist Socialist State’.

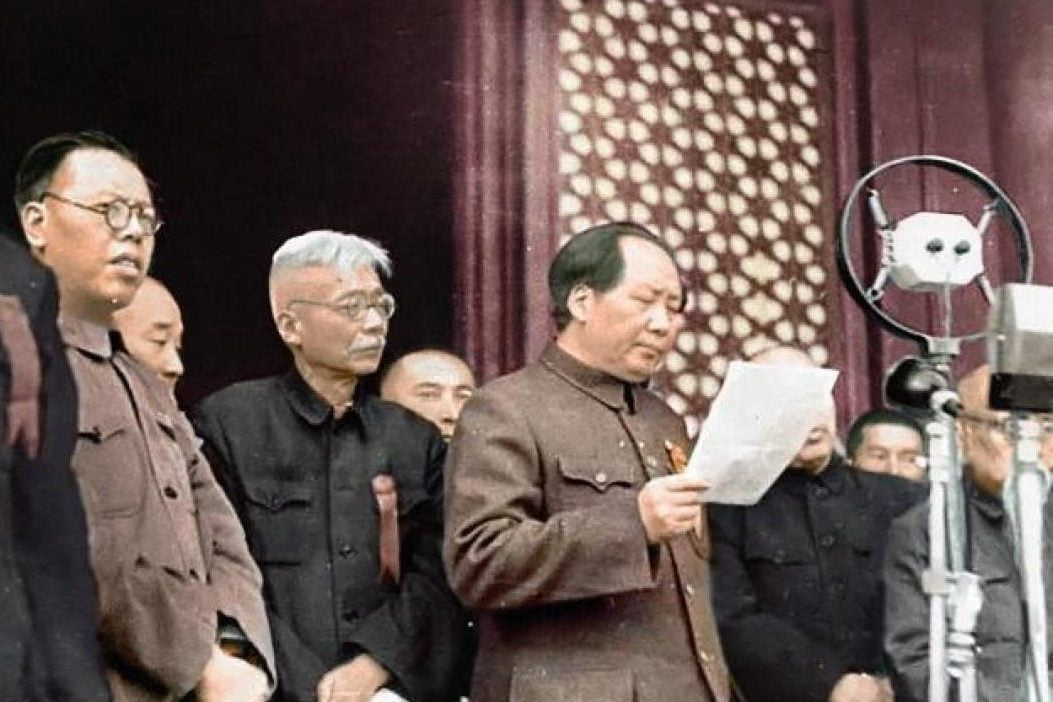

China

Yet up to the Russian revolution even Lenin denied the possibility of the victory of the proletarian revolution in a backward country. The Chinese revolution of 1944-9 did not proceed on the model of the revolution of 1925-7. It was a peasant war, which took place because of the complete incapacity of the bourgeoisie to carry out the tasks of the bourgois-democratic revolution – the ending of landlordism, national unification and the expulsion of imperialism – it ended with victory to the Chinese Stalinists.

The programme of the Chinese Stalinists was not fundamentally different to that of Castro later in Cuba: 50 or 100 years of ‘national capitalism’ and an alliance with the ‘national bourgeoisie’. Hence the belief of many American bourgeois that they were ‘agrarian reformers’.

Only the Marxist tendency in Britain argued against the Stalinists and the alleged ‘Trotskyist’ sects and explained the inevitability of Mao’s victory and the establishment of a deformed workers’ state.

At a time when Mao and the Chinese CP had the programme of capitalism and ‘national democracy’ we could predict the inevitability of proletarian Bonapartism as the next stage in China. This had nothing in common with the methods of the proletarian revolution in Russia in 1917.

Power was gained through the peasant war by giving land to the soldiers in Chiang Kai Shek’s army. Then, by balancing between the classes and playing them off against each other in Bonapartist fashion, once military victory was achieved, landlordism and capitalism were expropriated. Nearly all the so-called ‘Trotskyist’ sects now accept the accomplished fact. But never before in history has it even been theoretically posed that a peasant war on classical lines could lead to a workers’ state, however deformed. The workers in China were passive throughout the civil war for reasons we will not enter here. But here was a perfect example of one class – the peasants in the form of the Red Army – carrying out the tasks of another.

It is amusing now to see the sects without turning a hair, swallowing the idea that a ‘workers’ state’ was established in China by the peasant army, only because at the head of the army was the so-called ‘Communist’ Party. In classical Marxist theory this idea would be precisely considered hair-raising and fantastic. The peasants, as a class, are least capable of assuming a socialist consciousness.

It is an aberration of Marxism to think that such a process is ‘normal’. It can only be explained by the impasse of capitalism in China, the paralysis of imperialism, the existence of a strong deformed Bonapartist state in Stalinist Russia, and most important of all, the delay in the victory in the industrially advanced countries of the world. The colonial countries cannot wait. The problems are too crushing. There is no way forward on the basis of capitalism. Hence the peculiar aberrations in colonial countries. But the price for this, as in the Soviet Union, is a second political revolution to put the control of society, industry and the state in the hands of the proletariat. Only thus could the first genuine beginnings of the transition of socialism, or rather steps in that direction, commence.

The wide support for ‘socialism’ not only among the working class, but among the peasants and wide layers of the petit-bourgeoisie in the cities in colonial countries, is the expression of the complete blind alley of landlordism and capitalism in the colonial world in the modern epoch. It is also a result of the Russian and Chinese revolutions and their achievements in developing industry and the economy. It is this that lays the groundwork for the development of proletarian Bonapartism.

The state can be reduced to armed bodies of men, according to Engels. With the defeat and destruction of the police and army of Chiang Kai Shek, with the destruction of the army of Batista(1) in Cuba, power was in the hands respectively of Mao and Castro. The fact that nominally Mao was a ‘Communist’ and Castro a bourgeois democrat altered nothing.

Moscow’s Image

So far was Mao from the model of the proletarian revolution that on entering Shanghai and other cities, workers who had seized their factories and met Mao with demonstrations of red flags were instantly shot in order to ‘restore order’! The state created by Mao was in the image of Moscow, 1949, not Moscow 1917!

Mao, in typical Bonapartist fashion on the basis of the peasant army, always an instrument of (bourgeois) Bonapartism in the past, balanced between the classes. Having perfected a state in the image of Moscow, leaning on the workers and peasants, he could snuff out the bourgeoisie painlessly. As Trotsky put it, for a lion you need a gun, for a flea, a fingernail will do! Therefore, having balanced between the bourgeoisie and the workers and peasants in order to prevent the workers from taking power, Mao and his gang – after perfecting the state – could then crush the bourgeoisie before turning on the workers and peasants to crush whatever elements of workers’ democracy had developed.

The bureaucracy then developed a totalitarian one-party dictatorship, centred round the Bonapartist dictatorship of one single individual – Mao. But, not for nothing has Marxist theory given the task of achieving the socialist revolution and the transition to socialism to the working class. This is not an arbitrary role but because of the specific role in production of the proletariat which gives it a specific consciousness possessed by no other class. Least of all can the petit-bourgeois peasant develop this consciousness. A revolution based on the latter class by its very nature would be doomed to degeneration and Bonapartism. It is precisely because a proletarian Bonapartist dictatorship protects the privileges of the elite of state, party, the army, industry and the intellectuals of art and science that it has succeeded in so many backward countries.

Marxism finds in the development of the productive forces the key to the development of society. On a capitalist basis there is no longer a way forward, particularly for backward countries. That is why army officers, intellectuals and others, affected by the decay of their societies can under certain conditions switch their allegiance. A change to proletarian Bonapartism actually enlarges their power, prestige, privileges and income. They become the sole commanding and directing stratum of the society, raising themselves even higher over the masses than in the past. Instead of being subservient to the weak, craven and ineffectual bourgeoisie they become the masters of society.

Transitional Economies

The tendency towards statification of the productive forces, which have grown beyond the limits of private ownership, is manifest in the most highly developed economies and even in the most reactionary colonial countries.

There is no possibility of a consistent, uninterrupted and continuous increase in productive forces in the countries of the so-called third world on a capitalist basis. Production stagnates or falls. In the world recessions, particularly in the smaller countries, living standards fall. There is no way out on the basis of the capitalist system. That explains the terror regimes of bourgeois Bonapartism like that of Pakistan, Indonesia, Argentina, Chile and Zaire. But with bayonets and bullets, on the basis of an out-dated and antiquated system, only very temporary respite is given. Discontent multiplies and is reflected in the officer caste of the armed forces and throughout the society. This in turn leads to conspiracies of individuals and groups of officers.

The army is a mirror of society and reflects its contradictions. That and not the mere whims of the officers concerned, is the cause of the upheavals as in Syria. It is an indication of the agonised crisis of society, which cannot be solved in the old way. These strata of society can espouse ‘socialism’ of the Stalinist variety – proletarian Bonapartism – all the more enthusiastically because of their contempt for the masses of workers and peasants.

The horrible caricature of workers’ rule in Russia, China, and the other countries of deformed workers’ states attracts them precisely because of the position of the ‘intellectual’ educated cadres of that society. What is repulsive to Marxism is what attracts the Stalinists.

All that these states have in common with healthy workers’ states or with the Russia of 1917-23 is state ownership of the means of production. On that basis they can plan and develop the productive resources with forced marches at a pace absolutely impossible on their former landlord-capitalist basis. This is possible of course for only a limited period of time. At some point the Stalinist regimes become an absolute hindrance and a fetter to production. Russia and Eastern Europe are reaching these limits. In common with a healthy workers’ state on the accepted Marxist norm is the fact that they are transitional economies between capitalism and socialism.

But Marxism teaches that a movement towards socialism requires the control, guidance and participation of the proletariat. With a privileged elite in uncontrolled dominance and not reconciled to the loss of its status in a ‘withering away’ of the state, this produces new contradictions. As the corruption, nepotism, waste, mismanagement and chaos which bureaucratic control necessarily involves comes more and more into contradiction with the needs of social development, this manifests itself in the heightened antagonism between the proletariat and the bureaucratic elite.

Trotsky long ago explained that in the case of Russia the bureaucracy developed the productive forces in a way in which the bourgeoisie was incapable of doing, but at three times the cost to the masses. The bureaucracy fulfills the function, a relatively progressive function, which the bourgeoisie had accomplished in the past. But Trotsky explained that this role also engenders its own contradictions. The bureaucracy is in some senses even less prepared than the bourgeoisie to reconcile itself to the loss of privilege and power. Instead it grows even more to become a monstrous cancer on society. It can only be removed by political revolution.

This will be triggered either by events at home or the successful gaining of power by the proletariat and the constitution of a workers’ democracy in one of the advanced capitalist countries. It will be by social revolution in the West or by victorious political revolution in Russia and Eastern Europe that a healthy workers’ state and a workers’ democracy will be created. It must be emphasised that the only features these deformed workers’ states have in common with the ideal workers’ state is state ownership of the economy and a plan of production. Only one of the ‘idealist’ and ‘eclectic’ sects could discover a fundamental difference between the peasant war in which Mao came to power and the guerrilla war of Castro, based on peasants and semi-peasants and landless peasants as well as some ex-workers. There is not much difference, despite the bourgeois democratic ideas in Castro’s head which in any event were not all that different from the programme on which Mao fought the civil war.

At least in the last stages of the struggle, the participation of the working class, with the general strike in Havana, turned the scales in Castro’s favour. Nothing of this sort happened in the civil war in China of 1945-9. Nor was this kind of intervention desired by Mao; true, had it not been for the stupidity of American imperialism the outcome could have been different in Cuba. But with the impasse of Cuban capitalism like that of Chinese capitalism, just as Mao had used the strong proletarian Bonapartist state of Russia as a model, so Castro used Eastern Europe and China as models in his conflict with American imperialism.

In both cases this marked an enormous step forward historically. Landlordism and capitalism were eliminated. That meant the removal of the fetters of semi-feudal landlordism and of private ownership of industry. The monopoly of foreign trade, following the Russian model, is also a powerful progressive factor. These measures meant a gigantic release of the constraints on the productive forces. Hence in advance we could hail the Chinese revolution as the second greatest event in human history, the Russian revolution being the first. Nevertheless because of its Bonapartist character – and the inevitable vested interest of the bureaucracy in maintaining the rule of privilege, prestige, power and income for the ruling layers of the bureaucracy itself – the masses would have to pay with a second revolution before there could be a workers’ democracy on the level of that in Russia of 1917-23.

Because of the incapacity of the sects to apply Marxism and ‘Marxist philosophy’ in a concrete manner they have landed themselves in ludicrous contradictions. Thus they declared Eastern Europe to be state capitalist in 1945-47 – while Russia, which occupied Eastern Europe with the Red Army, was a ‘degenerated workers’ state’.

When Tito broke with Stalin, overnight, from mysteriously being ‘capitalist’, Yugoslavia became a healthier workers’ state than even Russia in 1917! This did not prevent these sects from simultaneously declaring Eastern Europe still to be capitalist. China remained ‘state capitalist’ according to them until 1951 or 1953. Then, ‘Hey Presto’, China, from being ‘state capitalist’, was mysteriously transformed into a ‘healthy workers’ state’!

All this muddle and theoretical confusion has never been explained by any one of these petit-bourgeois tendencies masquerading as Marxists. One sect claimed Cuba was a petit-bourgeois Bonapartist state while describing China as a relatively healthy workers’ state in which political revolution was not necessary. Not a single one of these tendencies was capable of analysing the main forces and processes of the epoch, in which the colonial world saw a caricature of permanent revolution in which weird and deformed workers’ states were being set up. Not a single one of them understood the meaning of the Chinese ‘cultural revolution’. Some hailed this as a second version of the ‘Paris Commune’! Only recently – some 30 years too late – some reluctantly concluded that the Chinese revolution was deformed from the start. Our tendency explained the process in advance of Mao’s victory.

All the objective conditions for a socialist revolution are now maturing in Western Europe, Japan and the USA. The process, however, will be protracted because of the weakness of the forces of genuine Marxism. It is the delay of the revolution in the West, and now its protracted character, which gives room for these peculiar regimes in the neo-colonial countries. They are reaching unbearable tensions with semi-starvation of great masses without a roof or a crust. The insolent parasitism and luxury of the landlords and capitalists in contrast, leaning on imperialism, invests all the contradictions in these societies with an explosive force. It is on the basis of this weakness of imperialism, the glaring rottenness and decay of landlordism-capitalism – which makes possible the development of the curious process of proletarian Bonapartism. Taking advantage of the revolt of the masses of peasants, petit-bourgeoisie and even workers, the elite of officers, intellectuals etc, can emerge, as in Ethiopia, with firm power in their hands on the basis of the support of the workers and peasants. They can perfect a ‘KGB’ secret police of their own to silence anyone who would object to their privileges.

The peasantry, by its very nature a class of individuals not bound together by production, is therefore the perfect instrument for bourgeois or proletarian Bonapartism. It is a class that can inherently be manipulated and deceived; a class that looks towards the ‘Tsar as a father of the people’, or to the god-head, Mao. The urban petit-bourgeois too have these attributes; in Germany and Italy they looked to Hitler and Mussolini as ‘leaders’. Only the proletariat stands firmly for genuine democracy – ie workers’ democracy in a workers’ state – which is the only system where its direct rule can be manifested.

Our tendency has explained and predicted these processes. There is no real possibility of moving forward in the colonial world on a capitalist basis. It is this, plus the lagging of the proletarian revolution in the advanced industrialised countries, which has led to these regimes taking ten steps forward and five steps back. They can – at least for a period in most cases – develop the productive forces with seven league boots, on the basis of proletarian Bonapartism. They carry out in backward countries the historic role which was carried out by the bourgeoisie in the capitalist countries in the past.

The whole essence of Trotsky’s theory of the permanent revolution lies in the idea that the colonial bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie of the backward countries are incapable of carrying out the tasks of the bourgeois democratic revolution. This is because of their links with the landlords and the imperialists. The banks have mortgages on the land, industrialists have landed estates in the country, the landlords invest in industry and the whole is entangled together and linked with imperialism in a web of vested interests opposed to change.

Under these circumstances the task of carrying out the bourgeois-democratic revolution fell on the shoulders of the proletariat. But the proletariat, having conquered power at the head of the peasantry and the majority of the nation, would not stop at the accomplishment of the bourgeois-democratic tasks of expropriating the landowners, unifying the nation, and expelling the imperialists. It would then pass on to the socialist tasks, the expropriation of the bourgeoisie and the setting up of a workers’ state.

But the socialist tasks could not be encompassed in a single country, especially a backward colonial country. The revolution would have to spread to the more advanced countries. Hence the term for this process, permanent revolution beginning as a bourgeois revolution, becoming a socialist one, ending in international revolution.

It is true that, owing to the development of the Stalinist bureaucracy and the reformist degeneration of the Communist Parties, exceptional difficulties have been put in the path of the proletariat in both advanced and backward countries. But the impasse of landlordism and capitalism in the so-called third world has been aggravated during the course of the decades since the outbreak of the second world war. For a period, the industrialised capitalist countries passed through a relative development of productive forces, once the political preconditions had been established by the betrayal in the early post-war period of Stalinism and reformism.

But while living standards in the West increased at least in absolute terms, in the ‘third world’ with few exceptions there was a decline in already low living standards. The decay of antiquated land relations under the inexorable pressure of the world market continued apace. A large surplus population of paupers, beggars and lumpens is endemic in the colonial world. On the old relations there is no way out. In Vietnam, Laos, Kampuchea, Burma, Syria, Angola, Mozambique, Aden, Benin, Ethiopia and as models, Cuba and China (which in their turn had the model of Eastern Europe as a beacon showing the way) there has been a transformation of social relations.

This is because of the rotten ripeness of world capitalism for the socialist revolution. But all history shows that where, for one reason or another, the new progressive class is incapable of carrying out its functions of transforming society, this is often done (in a reactionary way, perhaps) by other classes or castes. Thus in Japan big sections of the feudal lords became capitalists and in Germany – as Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky recognised – the landowning Junkers of East Prussia under Bismarck and the monarchy carried out the task of the national unification of Germany – a task of the bourgeois democratic revolution.

Attractive Power

As Marx long ago explained, there is no such thing as a supra-historical blue-print. It is necessary to take the material objective reality as it is and then explain it. That is the method of ‘Marxist philosophy’ and not the philosophical gibberish of the sects. But it is not only necessary to see objective reality as it is, but to explain the process that brought it into being, the contradictions encompassing it, the law of social movement which it represents and the future processes of contradictions and change which will envelop it. Its process of birth, development, decay and the changes which will destroy it.

Under the conditions of the decay of capitalism-landlordism in the colonial countries, all the social contradictions are aggravated to an extreme. Social tensions reach an unbearable level. Hence in one country after another in Asia, Africa and Latin America, bourgeois democracy is replaced by bourgeois Bonapartist dictatorships or proletarian Bonapartist dictatorships.

In the above-named ex-colonial countries not one proceeded on the model of the norm of the socialist revolution. Neither did the countries of Eastern Europe before them in the aftermath of the second world war.

The great Marxist teachers in the past have often explained that once the norm of the socialist revolution has been established in the main capitalist countries, it would have an irresistible appeal to the rest of the world and result in a painless transformation without conflict. Even the bourgeoisie would recognise the superiority of workers’ democracy, apart from the effect this would have on the world working class. Marx himself believed that in this way the backward areas of the world, and even the backward countries of Europe, would be brought forward by the advanced industrialised countries acting as a magnet and a model of socialism. Lenin and Trotsky conceived of the socialist revolution taking place in some backward countries first only with the leading role and participation of the proletariat. The proletariat would lead the petit-bourgeois masses, especially the peasantry, to the overthrow of landlordism and capitalism and then link the workers to the international working class and the tasks of the world revolution.

The Bonapartist totalitarian dictatorship in Russia, a completely deformed workers’ state, repels workers in advanced capitalist countries. This is because nothing remains of October except the abolition of landlordism and capitalism, a plan of production, plus the monopoly of foreign trade, albeit bureaucratically twisted and distorted.

But nevertheless the mighty achievements of the revolution, the productive advances, the abolition of backwardness bringing Russia to the position of the second industrial power of the world, have an enormous attractive power for the colonial masses. (This is further reinforced by the example of the Chinese revolution which in the space of less than a quarter of a century has transformed China into a mighty power.) In most of the colonial countries where it still exists, bourgeois democracy is a hollow and empty shell backed up at various times by ‘states of siege’, states of emergency and even martial law.

Consequently the lack of workers’ democracy in these proletarian Bonapartist states is not such a drawback in attracting the masses. It is a positive attractive feature as far as the professional and lower army officers are concerned. The solution of their most pressing problems of food, clothing and shelter loom large in the minds of the colonial masses.

Ethiopia

This in its turn has an enormous effect in the countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America. The bourgeois-Bonapartist regimes in the colonial countries are charged with terrible contradictions. Their problems are insoluble. They spend large sums on armaments, further exacerbating the poverty of the masses. They are inherently unstable. They provoke the hatred of the workers, the petit-bourgeoisie, the students and peasants. Even the weak bourgeoisie they represent comes into collision with them.

It is in this social soil that plots, counter-plots and conspiracies in the army flourish. The army (or armed forces) is always moulded in the image of society and is not independent of it. Where the army dominates, that indicates a crisis in society and a regime of crisis.

Different cliques, groups or even individuals at the top in the army come to reflect groupings, sections of classes or classes in society. They do not represent themselves but precisely reflect the antagonistic interests of different classes in society.

Under conditions of social crisis people change. This applies to classes and even individuals. Thus Marx explained that with the decay of feudalism a section of the feudal lords, bigger or smaller as the case may be, goes over to the side of the bourgeoisie in the bourgeois revolution. A section of the bourgeoisie, particularly the intellectual bourgeoisie, can also put themselves on the standpoint of the proletariat.

No more barren, formalistic, anti-dialectical, philosophically idealist, anti-‘Marxist philosophy’ idea in the history of the movement has been put forward than by those who argue that because Castro began his revolutionary struggle as a bourgeois democrat with bourgeois democratic ideas and goals that therefore he must remain a bourgeois democrat for all eternity. They forget that Marx and Engels themselves began as bourgeois democrats who broke decisively with the bourgeoisie and became leaders of the proletariat.

Under conditions of the crisis of capitalism in Portugal,(2) a semi-colonial country, a majority of the officer caste, sickened by the decades of dictatorship and the seemingly unending wars in Africa which they realised they could not win, moved in the direction of revolution and ‘socialism’. Only our tendency explained this process.

This gave an impetus to the movement of the working class, which then reacted in its turn on the army. This affected not only the rank and file, and the lower ranks of the officers, but even some admirals and generals who were sincerely desirous of solving the problems of Portuguese society and the Portuguese people.

This was something that would have been impossible in previous revolutions. Thus, 99 per cent of the officer caste supported Franco in the Spanish civil war.

True enough, because of the reformist and Stalinist betrayal of the Portuguese revolution which prevented it from being carried through to completion, there has been a reaction. The army has been purged and purged again to become a more reliable instrument of the bourgeoisie.

But how far this has succeeded remains to be tested in the events of the revolution in the coming months and years.

But what it has demonstrated is the need for a genuine dialectical understanding and interpretation of the events of the present epoch. If such a transfonnation was possible, in a semi-colonial but imperialist capitalist Portugal, how much more could similar processes take place in the newly independent countries of Africa and of Asia?

Events in Ethiopia have crushingly confirmed the theses we have worked out. There, the famine brought about by Haile Selassie and the landlord nobility, was the last catastrophe even the officer caste was prepared to tolerate. The callous indifference of the Emperor and the landlord class to the famine and the death from starvation of hundreds of thousands and possibly even millions, plus the accumulated social contradictions in a backward country under the pressure of imperialism, pushed the middle layers of the officer caste to organise a coup.

This in its turn awakened the movement of the small working class in Addis Abbaba and the students and petit-bourgeois layers in the capital and in the towns. It awakened the peasantry also into a cataclysmic movement to gain control of land. Thus the 1000 year old ’empire’ and its class structure crumbled to dust.

The crisis in the army and the attempts at counter-revolution, the further impetus this gave to the guerrilla war in Eritrea, the querrilla war in the Ogaden, aided by the direct intervention of Somalia, the uprisings of the Galla and other tribes, all acted as a spur to the revolution.

The movement of the classes in turn had its effect on the new ruling junta in the army. It produced splits and individual and group conspiracies of officers. These reflected the classes in battle in Ethiopia and the developing civil war in the whole country. Whatever the individual whims of the officers, they reflected (as in Syria) – and had to reflect – the class struggle taking place. Hardly any wished for a return to the old regime.

The model of the Emperor’s landlord semi-feudal regime was rejected by the bulk of the officer caste. But there were differences as to how far to go, which ended in armed conflicts and executions. This, in a distorted way perhaps, reflected the struggle of the classes in Ethiopia.

It ended in the victory of Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu. Already the land had been divided among the peasants and industry nationalised without compensation to the imperialists and the native capitalists (though of course compensation is not necessarily the decisive factor).

In the struggles Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu emerged victorious as a Bonapartist dictator under the influence of the wars and civil wars. In order to obtain mass support Mengistu, formerly a high-up officer of the Emperor, has been forced to go all the way. He has declared himself a ‘Marxist-Leninist’ (probably without reading a single word of Marx or Lenin) and set about creating a one party ‘Marxist-Leninist’ totalitarian dictatorship. This is in the image of Moscow or Peking. The landlords and capitalists are expropriated and the imperialist countries are without real influence on the processes taking place in Ethiopia.

In this case the process is clear. It is even clearer than in Mozambique, Angola or the former Aden, and this without a direct struggle against imperialist occupation.

The imperialists are too weak and debilitated to intervene directly by military means and can only grind their teeth in impotence.

But undoubtedly only the Militant foresaw these possibilities in advance for many countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The revolution, or rather the primary tasks of the revolution, in backward countries have been accomplished in the regimes mentioned above. Landlordism has been eliminated. Capitalism has been destroyed, the influence of imperialism dispelled.

Thus the bourgeois origin of the leadership of the guerrilla movement in Cuba was of third or fifth rate importance. What was important was the attempt to take action to bring Cuba back to neo-colonial status which precipitated the break of Castro with American imperialism.

It is the social and economic similarities which are decisive for a Marxist in the social overturns in these countries.

To carry through a revolution like that of Russia in October 1917 requires the consciousness, the action, the understanding and the active participation and movement of the proletariat itself in the overthrow of capitalism and landlordism. It requires organs and organisations through which the proletariat can move, such as soviets, shop stewards committees, trade unions and so on. After the victory of the rule of the workers, the checking and control can be effected by such organs of workers’ rule.

In a revolution according to the norm such ad hoc committees and traditional organisations are indispensable. They are a training ground for the workers in the art of running the state, of developing the solidarity and understanding of the workers. After a victorious overthrow of capital they become vehicles for workers’ rule, the organs of the new state and of workers’ democracy.

But where – as in Eastern Europe, China, Cuba, Syria, Ethiopia – the overthrow takes place with the support of the workers and peasants certainly but without their active control, clearly the result must be different. The petit-bourgeois intellectuals, army officers, leaders of guerrilla bands use the workers and peasants as cannon fodder, merely as points of support, as a gun rest, so to speak.

Their aim, conscious or unconscious, is not power for the workers and peasants, but power for their elite. They had and have their model in Stalinist Russia.The revolution – change in property relations -begins where the Russian revolution ended, Stalinist Russia of 1945-9, or if you prefer, Stalinist Russia of 1978. They are fundamentally the same; a one party totalitarian state where the proletariat is helpless and atomised, with an apparatus of control of the state by the officials. The guerrilla army chiefs, who with an iron hand imposed discipline, take control undoubtedly with the support of the masses but with no organs of workers’ rule independent of the state. Also, none of the rights and powers of the workers and peasants, which the existence of soviets as organs of workers’ power would mean, exist.

For a transition to a Bonapartist workers’ state such organs of workers’ democracy, indispensable for a healthy workers’ state, would be an enormous hindrance. They constituted a tremendous obstacle to the Stalinist bureaucracy in Russia, which had to wage a Herculean struggle and even a one-sided civil war to erase the last remnants of workers’ democracy, which stood in the way of their untrammelled and dictatorial rule. This was reflected through the one man dictatorship of Stalin and his successors.

What is important is that this was the model of ‘socialism’ for Mao, for Castro, for Mengistu, for the Burmese generals and for the Baathist ‘Muslim’ generals in Syria.

Army and Intellectuals

It is important to see that what all these variegated forces have in common is not the secondary personal differences but the social forces and class forces they represent.

Mengistu, Castro, the Burmese generals broke with their class background and the advantages or disadvantages of their bourgeois and university education and outlook. It is true that they did not put themselves on the standpoint of the proletariat – as Marx and Lenin did – but they accepted the much easier ‘socialism’ which entailed the individual rule of them and of their elite on the backs of the working class and peasants.

All individual differences are stamped out by the decisive class and economic changes which they have presided over in their countries and their societies.

All the self-styled ‘Marxist-Leninist’ sects have not even understood the ABC of Marxism as taught by its founder and echoed by Lenin and Trotsky. This is something to marvel at. The emancipation of the working class is the task of the workers themselves. This is not because it is some kind of penance which the workers must do or because they are ‘nice people’. It is because without this there is the inevitability of a small minority having a monopoly of culture they will then use – and inevitably abuse – against the interests of the workers and peasants and in their own interests. Also, mobilisation of the proletariat, its conscious struggle for power, and fight for workers’ democracy, transforms the proletariat and fits it for the task of workers’ rule. This then partially rubs off onto the peasants and petit-bourgeoisie which follow the proletariat in both the advanced and the backward countries. This process does not take place with the struggle of the petit-bourgeois guerrilla bands or where radical army officer cliques take power.

Thus, the intellectual and army elite in all the social revolutions and overturns in the countries mentioned took state countrol firmly into their own hands. They had the passive – or more or less active support – of the masses. But there was not the conscious organised movement of the proletariat. The peasants and petit-bourgeoisie are not a viable substitute for the ‘self-movement’ of the proletariat.

It is a striking fact that in the case of every sect, they accept Mao and the Chinese revolution ex-post-facto and find in the ‘Communist’ badge of Mao the excuse for this. In reality Mao was an ex-Communist who had broken with the proletariat and put himself at the head of a peasant war.

The fact that he later balanced between the classes and in typical Bonapartist fashion, leaned on the workers for a time, alters nothing. The fact that the Peking gangsters called their hideous caricature ‘socialism’ or sometimes the dictatorship of the ‘proletariat’ also alters nothing. There is no fundamental difference economically or socially between any of these regimes. This means that the secondary differences in comparison with the fundamentals are only of trifling importance.

Lenin’s Mistake

It is no accident also that all the sects base themselves on the mistake of Lenin in What is to be Done – that the proletariat on its own is capable only of ‘trade union consciousness’ and not ‘socialist consciousness’. In reality this is not Lenin’s idea but appropriately Kautsky’s. Lenin discovered his mistake, and Lenin’s works, as those of Marx and Engels and Trotsky, not to add Luxemburg and Mehring, are the living refutation of this idea. In all 55 volumes of Lenin’s works there is never again the repetition of this error. In fact, without idealising the proletariat, as with all the great Marxists – all his works, down to the smallest article, are saturated with confidence and trust in the mighty power of the proletariat as the only vehicle which would lead mankind to socialism. This, of course, comes from the dialectical materialism of Marx.

In reality all these gentlemen of the sects have a haughty if secret – and sometimes not completely secret at that – contempt for the working class. Dialectically, while embracing enthusiastically this false idea about trade union consciousness, at the same time, they worship at the shrine of Ho Chi Minh or Mao or Castro or Tito or some other proletarian Bonapartist dictator. They are incapable of understanding the process of history and the temporary conjuncture of the economic upswing which led to a long lull in the class struggle in the West and the continuing crisis of society in the underdeveloped world. This was one of the corollary factors of the West’s boom and inevitably led to the rise and development of proletarian Bonapartism in the colonial world, which the dominance of Stalinism in Russia and the predominance of Stalinism and reformism in the workers’ movement in the world contributed to. Only genuine Marxism has been able from the beginning to explain all these ‘outlandish’ phenomena from the viewpoint of the working class and the class nature of society and the organic crisis of world capitalism which is manifested first of all at its weaker and more backward extremities.

All these proletarian Bonapartist regimes are temporary aberrations on the road of the world revolution. The excrescence which Stalinism represents will be eliminated almost in passing when the mighty proletariat of one of the advanced countries takes power in the West or the regimes of Russia and Eastern Europe are regenerated by the overthrow of bureaucracies.

In a number of works we have traced the contradictions and inconsistencies which the sects show on the question of what is a healthy workers’ state with ‘bureaucratic deformations’, or what is a deformed workers’ state. Though both are based on state ownership, they are fundamentally different in their super-structure. For that reason a political revolution is necessary in the case of a deformed workers’ state before a ‘workers’ democracy’ or ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’ in its political as well as economic sense, can be established. On the other hand, a workers’ state with ‘bureaucratic deformations’ is a workers’ state under conditions of backwardness and isolation which can still be reformed through the restoration of party, trade union and state democracy, ie a return to the control of the workers and peasants and where, if only in vestigial form, these organisations still exist under the pressure of the workers.

Some sects have bowed down before Castro as the leader and organiser of a ‘healthy workers’ state’. They went even further and compared his ‘struggle against bureaucracy’ with that of Trotsky against Stalinism. They actually committed the indecency of publishing the photographs of Trotsky and Castro together as fighters against bureaucracy and for democratic socialism. They thus showed that they understood neither the role of Trotsky as an immortal fighter against the Stalinist bureaucracy nor Castro’s role as the incarnation of the Cuban Stalinist bureaucracy.

Words are cheap. ‘Castro’s struggle’ against the Cuban bureaucracy was no different in essence to that of Stalin on occasions against the Russian bureaucracy. Stalin as a Bonapartist dictator sometimes attacked the ‘bureaucracy’ in words. He went further on occasions and leaned on the workers and peasants. This happened when the greedy bureaucrats went too far in their swindling, speculation and plundering of the state and threatened to devour the foundations of the state.

Stalin took action even against high-up bureaucrats and certainly against wide sections of the lower ranks of the bureaucracy. This was to preserve the Stalinist system by making scapegoats of some bureaucrats, especially the lower ranks.

Fundamentally, Castro’s role in Cuba is the same. True, he played the leading personal role in the guerrilla war, the overthrow of Batista, the movement towards expelling imperialism, and overthrowing landlordism and capitalism.

Stalin had lived through a proletarian revolution together with the existence of a workers’ democracy, yet he carried out a counter-revolution against it. But right from the first day, the Cuban revolution was deformed and distorted. The proletariat never held political power directly as in Russia. The fact that even today probably the decisive bulk of the Cuban people, as the Chinese people too, support the regime at this stage, alters nothing as to its character. Castro’s strictures against bureaucracy, like Stalin’s, are necessary if he is to preserve the role of ‘Bonapartist arbiter’ and ‘father of the people’.

Now, when dealing with Ethiopia, some of those who bow the knee before Castro, declare Mengistu – whose regime is basically a copy of that of Russia, China and Cuba – to be ‘fascist’. This particular example of contortions and eclectic acrobatics can only be greeted with gales of laughter by genuine Marxism.

State Capitalism?

Why is Mengistu’s regime ‘state capitalist’ and different to the others? There is no explanation. They merely echo the arguments of the student, Maoist ultra-lefts in Ethiopia. At least the Ethiopian Maoists have the consistency to declare – as the Maoists have done everywhere – that Russia too is ‘state capitalist’.

The proof of the ‘fascist’ character of the Mengistu regime, they claim, is the vicious repression, the executions, the repression of national rights and the national revolutions of a similar character to that of Ethiopia – of Eritrea and the Ogaden – and the suppression of other national minorities. The crushing and dissolution of independent trade unions and all the nascent democratic organs of self-expression of the workers and peasants is certainly to be condemned. So also is the concentration of power into the hands of the Army junta clique and the dictatorship of Mengistu.

But one rubs one’s eyes in disbelief at the shallowness of the ‘Marxism’ of these self-styled Trotskyists’. For every crime committed by Mengistu in this regard, Stalin committed a hundred times more! The repression of independent organs of the workers must have reached a state of perfection by the bueaucracy in Russia. Puppet ‘unions’ exist which resemble the Arbeitfront of the Nazis in Germany. The Russian ‘Communist’ Party is the arm of the bureaucracy itself and has long ago ceased to be a workers’ party. Concentration camps, or ‘labour camps’ as they are called, and psychiatric ‘hospitals’ have been established for all dissidents – right or left.

The national oppression of the minorities, and especially of worker dissidents, reached levels never reached even under Tsarism. A one-party totalitarian machine has been established without allowing any opposition anywhere among workers, peasants and intellegentsia. The regimentation of art, science and government into a Stalinist straitjacket, without any independent initiative or thought, has been unequalled in history except, possibly, in Hitler’s Germany. More or less, that is the picture common to all the proletarian Bonapartist states, including China and Cuba.

Some of the sects pick up the characterisation of the Mengistu regime from the Maoists. They also support the heroic guerrilla peasant war in the Ogaden and in Eritrea, which, if victorious, would probably end in a carbon copy of Cuba or of Mengistu’s Ethiopia. That would be inevitable with a backward economy and with the limited nationalist leadership looking to their own resources alone and not seeing the necessity of linking up with the workers of the advanced capitalist countries. If there is a struggle for national rights of these peoples – so long as there is not the direct intervention of imperialism – we would give critical support to the struggle as we would for example to the struggle of the Ukranian people for independence from Stalinist Russia. An independent socialist soviet Ukraine would prepare the way for a genuine and voluntary socialist soviet federation of all the peoples of the USSR. This could only be achieved by the overthrow of the Russian Stalinist bureaucracy by the Russian working class.

Support for Revolution

Unfortunately in Eritrea and the Ogaden, as in Ethiopia for the next period, democracy will receive short shrift. This is inevitable on the bases of a peasant war, as well as the Stalinist ideology of their leaders.

But as we did in the case of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia (Kampuchea) and for that matter China also – we would give support without closing our eyes to the inevitability of Stalinist totalitarian regimes whatever the result of the conflict.

Because of its character as a national struggle (though on the basis of state ownership and the elimination of landlordism and capitalism) and the limited outlook of its leadership, neither the Somalis nor the Eritreans have a means of influencing or winning over the peasant soldiers of Ethiopia. They too have carried through a revolution and are influenced by the national idea of a united Ethiopia.

The proletarian and far sighted policy of Lenin – in standing firmly for the bourgeois-democratic right of self-determination – has no place unfortunately in the policy of the Ethiopians. But neither is there present, on any side in the conflict, the other policies of Marxism – democratic-centralism in the Party, democracy in the soviets, trade unions and so on.

Our policy is dictated first by the international socialist proletarian revolution and its interests. The defeat of imperialism and the overthrow of landlordism and capitalism in the Horn of Africa are big steps forward.

This is despite the conflict between ‘socialist states’ which sows confusion among the advanced workers and the proletariat generally. The complexity of the problem and the need to keep our ideas clear is shown by the way imperialism and the Russian and Cuban bureaucracy have changed sides.

Yesterday the imperialists supported Haile Selassie and the landlord-capitalist regime in Ethiopia against Somalia and the guerrilla movement in Eritrea. Russia and Cuba financed, armed and organised the Somali state and supported the guerrillas in Eritrea with arms, finance and technical assistance. Ethiopia assumed more importance in their eyes, with the collapse of the Emperor, followed by the overthrow of the semi-feudal landlord-capitalist regime. Ethiopia has 35 million people against approximately 2 or 3 million each in Eritrea and Somalia.

Opportunistically taking advantage of the civil war in Ethiopia, organised by the landlord-capitalist counter-revolution, President Barre of Somalia sent troops into the Ogaden. He hoped for the disintegration and collapse of the Ethiopian revolution. He was nationally limited and short-sighted, interested only in a ‘greater Somalia’. Undoubtedly the imperialists, surreptitiously through the semi-feudal reactionary Arab states like Saudi-Arabia, gave support to the Somalis, as they now give support to the Eritreans despite the social character of the movement in Eritrea. They wish to weaken Ethiopia and strike a blow against the Russian bureaucracy.

The Russian bureaucracy and Castro have changed horses in mid-stream after vainly attempting to persuade the Somali rulers to make a compromise and establish a federation of Eritrea, Somalia and Ethiopia. This would undoubtedly have been the best solution, given the character of all these regimes either as Bonapartist deformed workers’ states, or such states in the process of formation.

When the Somalis rejected this proposal the bureaucracy switched sides. It is not certain that the Ethiopians were in agreement with this proposal either. Now they are trying to negotiate some form of agreement between Eritrea and Ethiopea. If the Eritreans do not accept some form of limited ‘autonomy’ Cuba and Russia seem certain to support the crushing in blood of the Eritrean attempt at self-determination. The imperialists, unable to intervene directly, will weep crocodile tears about the national and democratic rights of the Eritrean people. (Yesterday they brutally tried to suppress the rights of the Vietnamese people.)

But what is really entertaining about these dramatic conflicts is the position of some of the sects. They solemnly declaim that Russia (correctly) is a deformed workers’ state and Cuba (incorrectly) a relatively ‘healthy’ workers’ state. But in no way do they explain how and why the relatively ‘healthy’ workers’ state of Cuba or the deformed workers’ state of Russia actively helps the ‘fascist’ state of Ethiopia to establish itself and suppress the national rights of the people of Eritrea who are attempting to establish a ‘Marxist’ regime and the Somalis of the Ogaden and the other minorities.

Undoubtedly, on the basis of land distribution, the overwhelming majority of the Ethiopian peasants support the Ethiopian regime for want of an alternative.

It is theoretically possible of course that for the purpose of ‘defence’ against other capitalist states, a deformed workers’ state or even a healthy workers’ state could ally itself with a reactionary or fascist state. Stalin’s Russia did this in 1939 with the ‘non-aggression’ pact with Hitler’s Germany.

But what strategic necessity was there for Brezhnev and Castro to switch from supporting Somalia and Eritrea to their ‘fascist’ rivals? The rulers of the deformed workers’ states would look with trepidation at the rise of a healthy workers’ state in the industrialised countries because of the social reverberations it would provoke in their own countries. But they would welcome the establishment of social regimes on the pattern of their own regimes in the backward and neo-colonial countries.

This strengthens them internationally against their capitalist imperialist rivals. The basic world antagonism between the social structures of these countries and capitalist countries remains.

Stalinism and Fascism

Ethiopia is a country far more backward than Russian Czarism or even pre-revolutionary China, and is under conditions of civil war on every front. With a leadership which takes Cuba and China as its model, without revolutionary training, this officer leadership has moved towards Stalinist conceptions in the course of the revolution. But we cannot throw out the baby with the bathwater. We must separate out the enormously progressive kernel from the reactionary wrappings. Landlordism and capitalism have been eliminated and this decisive fact will have far-flung effects on the whole of the African revolution in the coming epoch.

Not for nothing did Trotsky explain to the American Socialist Workers Party that, separated from state ownership of industry and the land, the political regime in Russia was fascist! There was nothing to distinguish the political regime of Stalin from that of Hitler except the decisive fact that one defended and had its privileges based on state ownership while the other had its privileges, power, income and prestige based on the defence of private property. That was a fundamental and decisive difference! There is no difference in the fundamentals of economic and political structure of Ethiopia from China, Syria, Russia or any of the deformed workers’ states.

The latest events in Indo-China have served again to show the ridiculous contortions of the policies of all the sects. Our tendency gave wholehearted support to the struggle of the Vietnamese ‘Communist’ Party of Ho Chi Minh and its Laotian and Cambodian off-shoots in their peasant guerrilla war against American and world imperialism and their native puppets.

We supported the struggle unconditionally and wholeheartedly. We supported it because it was a colonial war for liberation. We would have supported such a war even under bourgeois or petit-bourgois leadership which had fought merely for the right of national self-determination alone. But it inevitably became a war for social liberation as well as national liberation – in the sense of fighting for the elimination also of landlordism and capitalism. Without this, the struggle could not have been carried on for decades against overwhelming military odds.

How far the sects have strayed from the Marxist or Trotskyist method was shown by the polemics between two different sects of the same international tendency about how far the Vietnamese were ‘unconscious’ Trotskyists operating on the basis of the permanent revolution.

None of these worthies have understood the peculiar character of the epoch as far as the colonial or ex-colonial areas of the world are concerned. Nor have they understood the inevitable perversion of the revolution under either open Stalinist – or pseudo-communist leadership – or that of radical sections of the officer caste. They have not understood the inevitable consequences when a colonial revolution is led to its progressive and ‘final’ conclusion of eliminating capitalism and landlordism but when the main force is not that of the working class with a Marxist leadership.

When the main force is a peasant army using classic peasant tactics of guerrilla war, then it must result in a ‘deformed workers’ state’ even if that were not the aim of the leaders. In the event of an army coup of the younger officers, allied to ‘intellectuals’ and students, the consequences would – inevitably – be the same.

This is particularly the case given the world environment of strong Bonapartist workers’ states, in the form of Stalinist Russia and other countries. Taken together with the existence of the imperialist powers there could be no other outcome.

Of course if there were in existence healthy workers’ states – for instance in Russia, or one of the big industrialised states of Europe, or Japan – then the results and the possibilities would be entirely different. The proletariat and people of the advanced workers’ states would give aid and assistance to a workers’ state in a backward country, linking the economies together, and sending tens of thousands of technicians to small countries and hundreds of thousands to one with a big population. That would mean rapid industrialisation plus workers’ democracy. That is what Lenin meant when he said Africa could move straight from tribalism to communism.

But given the present relationship of class forces in international affairs, with classical reformism and Stalinist reformism dominant in the workers’ movement of the advanced countries, such a conclusion in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos was ruled out.

Indo-China Clashes

That is why our tendency, while wholeheartedly supporting the Vietnamese and Indo-Chinese revolutions, warned the workers and peasants of these countries that while they should actively support the struggle and fight for social and national liberation, at the same time the dominance of the struggle by the Stalinist leadership would mean that while an enormous social step forward would be taken by the victory of the national liberation movement, it would be succeeded by a new enslavement by the totalitarian Stalinist bureaucracy. Without a Marxist party and without Marxist leadership the goal of the ‘Communist Party’ leadership would be a state in the image of the so-called ‘socialism’ of Russia or China.

We appealed to the advanced workers of Britain, America, France and the world, to support the social and national liberation struggle of the Indo-Chinese peoples, because it weakened imperialism and world capitalism. The liberation of the productive forces of these countries, by the overthrow of the rule of capital, would be of immense long-term benefit to the people of these countries and also to the world proletariat.

But we never deceived ourselves or the workers and peasants of the world as to the inevitable nature (the class relationship of forces) of the regimes which would be set up in these countries.

We warned of, and predicted, the inevitable setting up of nationalist totalitarian Stalinist regimes in these countries but even we had not expected just how far they would go in their distortions.

The armed clashes between Cambodia and Vietnam are a crushing condemnation of all those ‘Trotskyist’ sects in Britain and internationally who did not understand the class nature of these regimes and their Stalinist character. There was no surprise in these events for our tendency. The clashes on the borders between Russia and China when tens of thousands were killed had shown what nationalist bureaucrats are capable of.

These bureaucracies cannot look beyond the boundaries of the national state. Behind these clashes in former Indo-China are the aspirations of the Vietnamese to set up an Indo-China federation of ‘socialist states’. Obviously this would have been of immense benefit to the economies of all these countries. But the reason that the Cambodians are against the setting up of such a federation is that under conditions of Bonapartist totalitarianism they would inevitably come under the nationalist domination and national oppression of the Vietnamese bureaucracy. Leaving aside the virulent national chauvinism of the Cambodian Stalinists, this would be as inevitable as it was in Stalinist China and in Russia.

For the same reason, the Vietnamese Stalinists, in their turn, would refuse to federate with Stalinist China. They know, as the minorities in China have seen, that they would come under the national oppression of the Chinese bureaucracy. Even though economically it would be of immense benefit, they would not agree to this, no more than would the Chinese bureaucracy agree to a federation with Russia, though economically and even in terms of world power politics, it would be colossally beneficial to the peoples and the economies of both these countries. What stands in the way are the national vested interests of the bureaucracies of all these countries.

Only workers’ democracy, without any hint of national superiority or advantage as in the days of Lenin and Trotsky, can have such a programme. But a Bonapartist regime, basing itself on privilege and inequality, is incapable of such a policy: the chauvinistic excesses of Stalinist Russia and China are proof of this. Bonapartist totalitarian regimes by their very nature, can never look beyond the narrow horizon of the national state. By the very nature of bureaucracy and its privileges they are nationally limited.

Basing themselves on peasants, students and intellectuals, and without the decisive domination and participation of the working class, they are inevitably nationally limited.

Afghanistan

The working class can secure its emancipation and the domination of society only by overcoming all the prejudices of the past – national, racial, caste, sex or any other. But only the working class and no other – and only under Marxist leadership at that – is capable of this feat. But the emancipation of the workers means the emancipation also of the petit-bourgeois strata in society who, under the leadership of the working class, and only under these conditions, would be capable of rising to these heights.

The petit-bourgeois and the intellectuals can adopt the standpoint of the proletariat only by breaking completely with their origins and the outlook of their class. Under modern conditions that is extremely difficult where genuine Marxists, as in the early days of Marx and Engels, have been reduced to a handful.

This is particularly the case today when the struggle is not merely in the ideological sphere but where the immediate issue in country after country is the transformation of society. In this situation it is easy for the intellectuals to come under the domination of the muddled ideas of Stalinism in its various forms.

Only a strong workers’ movement dominated by Marxism could make the metamorphosis of such intellectuals possible.

This is especially difficult in colonial or neo-colonial countries where the problems are immediate, where the masses live an almost animal existence, where also there are insuperable obstacles to modernisation and the development of society on the basis of the semi-feudal landlord capitalist regimes.

It is easier for the intellectuals, the radical officers, even civil servants and upper layers of professional people, doctors, dentists, lawyers and so on to make the transition to Stalinist Bonapartism than to support genuine but tiny Marxist tendencies. Especially this is so in most of these countries where ‘Marxism’ does not exist as an organised tendency.

The ‘Marxist-Leninism’ of Russia, China or Ethiopia suits them perfectly. It fits all their prejudices. A ‘socialism’ where the elites of state, party, industry, army and the professions have a standard of living way above that of the masses seems perfectly normal and natural to them. A society where these strata become the dominant and governing caste, has an enormous attraction for them, especially as they see the enormous strides which backward countries make with a forced march of ‘socialism’.

Thus it is easy for them to rationalise their class position. They have a hatred of the corrupt landlords and capitalists under whose control their societies and countries are either decaying or only inching ahead. They have a contempt for the downtrodden masses of peasants and even for the weak working class.

These stratas, apart from their economic position, are imbued with an overwhelming conceit and concern for their own importance in society. They are concerned with perks, status, standing, power, privileges, income and prestige. Thus, it is easy in the modern world to see how they can embrace ‘socialism’ on the pattern of Cuba, for example.

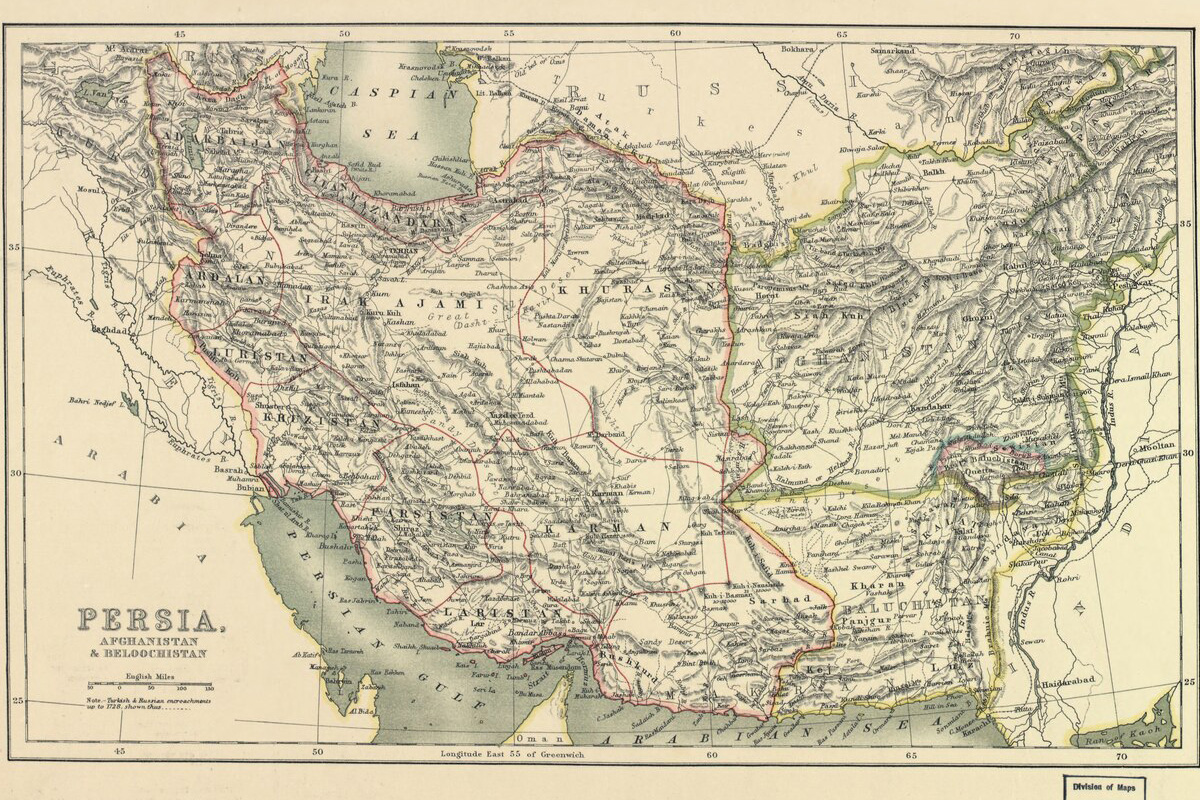

In the past period the fresh example of Afghanistan underlines the analysis we have made of the colonial revolution. The ‘Communist’ Party of this terribly backward country was only formed in the last decade or so. Like the Baath Party in Syria, it had no difficulty in swallowing the doctrine of ‘Islam’ as well as ‘communism’. It has done so because religious superstition has deep roots among the overwhelmingly backward peasant majority, 90 per cent of whom are illiterate.

Complete Transformation

Now, as with the Baath Party in Syria, the CP leaders in Afghanistan have allied themselves with the radical lower and middle ranks of the officer caste in the army.

The immediate issue which precipitated the coup was famine – as in Ethiopia – and the impossibility of the corrupt, semi-feudal Asiatic ruler, to cope with it. Afghanistan has had many coups in the past decades leading to different tribal leaders and groups gaining power. They merely changed the tops, leaving the social structure intact. The same corruption inevitably developed, leading, when the imposition had become unbearable on the masses, to a famine, or through foreign intrigue, to a new coup. Thus, social relations were contained in the same vicious circle. This new coup opens up the possibility of striking in a new direction. ‘Communists’ have become Prime Minister and President and also have a dominant role in the government. This indicates in which direction the officers wish to go. One of the first acts of the new regime has been to seize the lands of the monarchy, which, though overthrown by the former Daud(3) regime, still possessed 20 per cent of the land in Afghanistan! This is a new departure and may be the beginning of a complete transformation of social relations.

As in Poland, where the Polish Stalinist bureaucracy came to an agreement with the Catholic church, so in Afghanistan the Communist Party leadership, together with the officers, can arrive at an agreement with the mullahs of Islam. The fact that Taraki, the new Prime Minister, is the leader of a so-called Communist Party alters nothing. He pursues the same policy as that of the Syrian leaders of the Baath.

In the case of Afghanistan, only two roads are possible at this stage. The working class is miniscule. Sections of the intelligentsia, and apparently the majority of the officers and a great part of the professionals, want to construct a modern civilised state. The peasants want the land.

On the road of capitalism and landlordism, there is no way forward. The army officers wish to take the road traversed by Outer Mongolia. In fact these peculiar changes are only possible because of the international context. The crisis of imperialism and capitalism, the impasse of the backward countries of the third world and the existence of the proletarian revolutions in the West, are powerful factors in the case of Afghanistan.

The barbarous regimes also of Pakistan, Iran and nearby India have no attractive force. The army officers, many, if not most, trained in Russia, are attracted when they see the consequences of the Stalinist regime. It has a big effect on the tribesmen, of similar peoples and even the same tribes, in areas bordering Russia when they see the modernisation of areas of Russia which formerly had as low a standard of living, and just as great illiteracy and ignorance as themselves.

Marxist Approach

The industrialisation, complete literacy and high standards in comparison to Afghanistan, are bound to impress these strata. In contrast, the backwardness and barbarism on which the nobility thrived in Afghanistan cannot but appal all the best elements – the intelligentsia, the professionals and even the officer caste. They wish to break out from poverty, ignorance and dirt from which their country suffers. The capitalists of the West, with unemployment and industrial stagnation, offer them nothing. They wish to break away from the vicious circle of tribal rulers and different military regimes which change nothing fundamental.

The world crisis of capitalism hits the backward regions of the world even harder, and impels them to draw the conclusion that capitalism offers no way forward.

The ‘republican’ regime of Daud – incidentally, backed and propped up by Moscow in the past – alters nothing. The upheavals and coups, leading to mere changes of dynasties by different clans of the nobility during the last fifty years have been completely sterile. The nobility and the relations on the land on which they were based, was the main obstacle to modernisation.

Under these circumstances, if the new regime leans on the support of the peasants and transforms society, then the way will be cleared for the development of a regime in Afghanistan, like that of Cuba, Syria or Russia. This, for the first time for centuries, will bring Afghanistan society forward to the modern world. If the socialist transformation is completed, it could comprise a new blow at capitalism and landlordism in the rest of capitalist-landlord Asia, especially in the area of South Asia. It will have incalculable effects on the Pathans and Baluchis of Pakistan and will have a similar effect on the peoples on the borders of Iran. The rotting regime of Pakistan in coming years will face complete disintegration. A revamping of social relations in Afghanistan can further contribute to the decay of this regime.

The tribesmen will be influenced by the process taking place among their brothers across the borders. On the North West frontiers of Pakistan and among the Baluchis there is already endemic and simmering revolt, with these peoples looking towards a unity with their brothers in Afghanistan. The effect would be in widening circles, the repercussions of which could be felt in Iran and further afield, also in India.

This is the road which the ‘Communist Party’, which holds power together with the radical officers, will take. The opposition of the old forces in Afghanistan, as in Ethiopia, will in all probability impel them in this direction.

If they temporise, possibly under the influence of the Russian ambassador and the Russian regime, they will prepare the way for a ferocious counter-revolution based on the threatened nobility and the mullahs. If successful, counter-revolution would restore the old regime on the bones of hundreds of thousands of peasants, the massacres of the radical officers and the near extermination of the educated elite. For the moment – until there is a movement of the only advanced class which can bring a transition moving in the direction of socialism in the industrially developed countries – the most progressive development in Afghanistan seems at the present time to be the installation of proletarian Bonapartism.

While not closing our eyes to the new contradictions this will involve, on the basis of a transitional economy of a workers’ state, without workers’ democracy, Marxists, in a sober fashion, will support the emergence of such a state and the further weakening not only of imperialism and capitalism but also of regimes basing themselves on the remnants of feudalism in the most backward countries.

Notes

(1) Fulgencia Batista was the US backed Cuban dictator, from 1933 until his overthrow by the guerrilla army led by Castro in 1959.

(2) On 25 April 1974, a movement of armed forces officers overthrew the Caetano dictatorship in Portugal, ushering in a revolutionary crisis.

(3) Mohammed Daud came to power, overthrowing the monarchy in 1973. He was overthrown by the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council on 27 April 1978, which brought the Taraki regime to power.